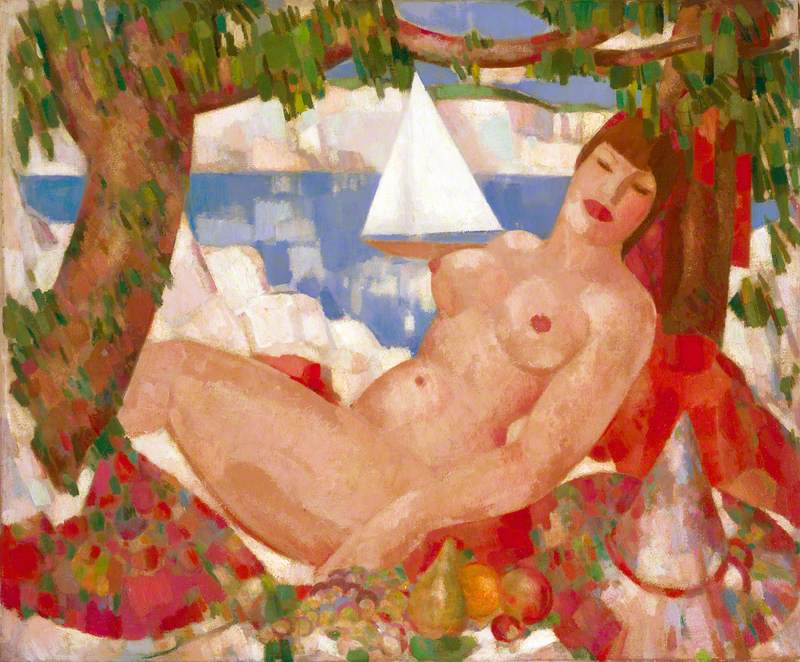

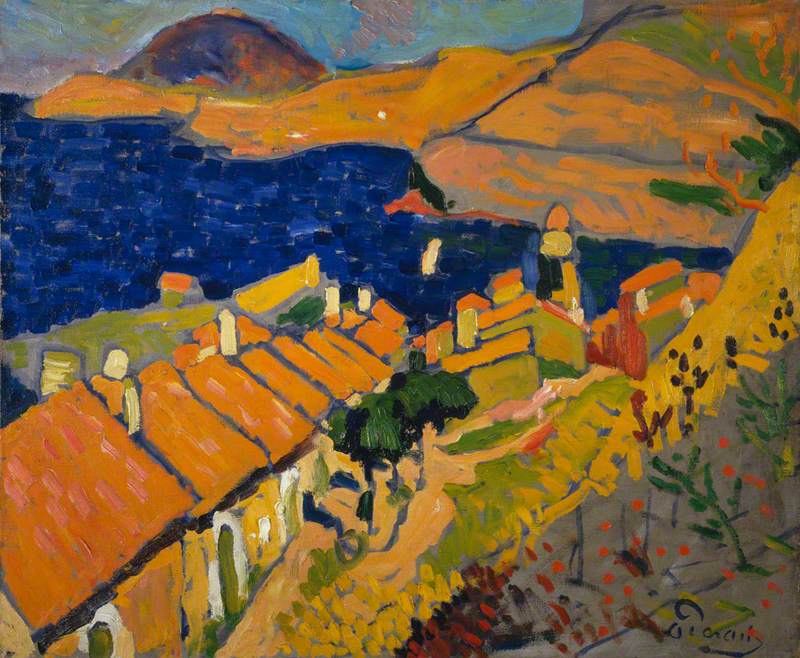

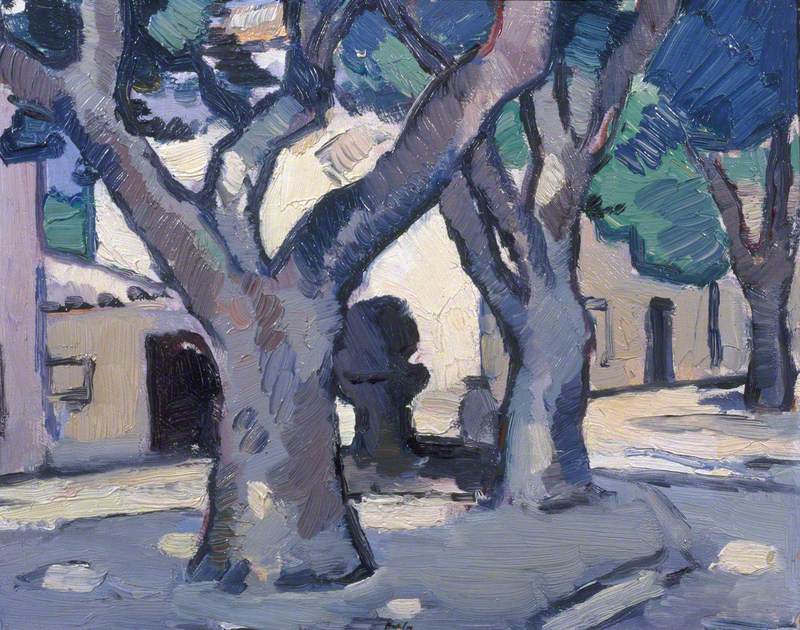

Anne Redpath's art grew out of two antecedents: the experiments with figurative form and colour in French Post-Impressionism and the development of that influence in the work of the Scottish Colourists.

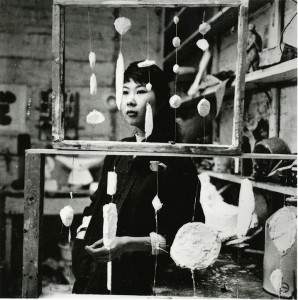

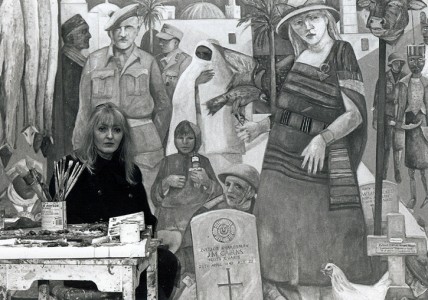

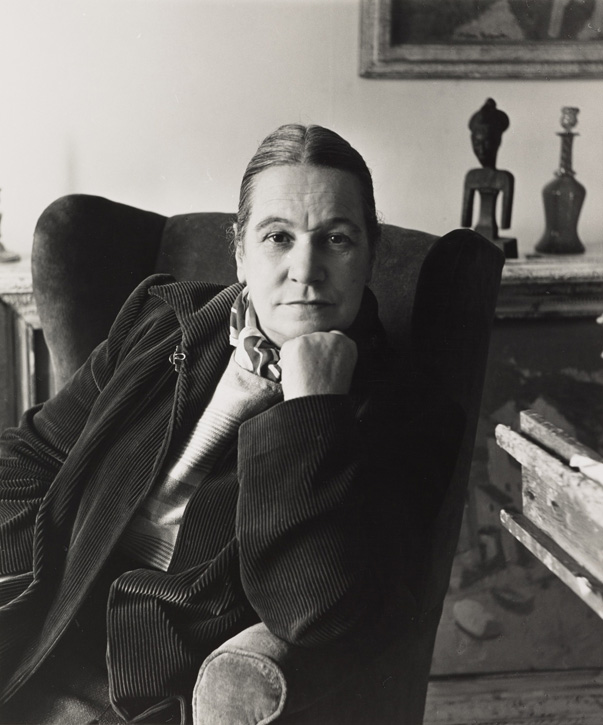

Anne Redpath, 1895–1965. Artist.

1949, silver gelatine print photograph by Lida Moser

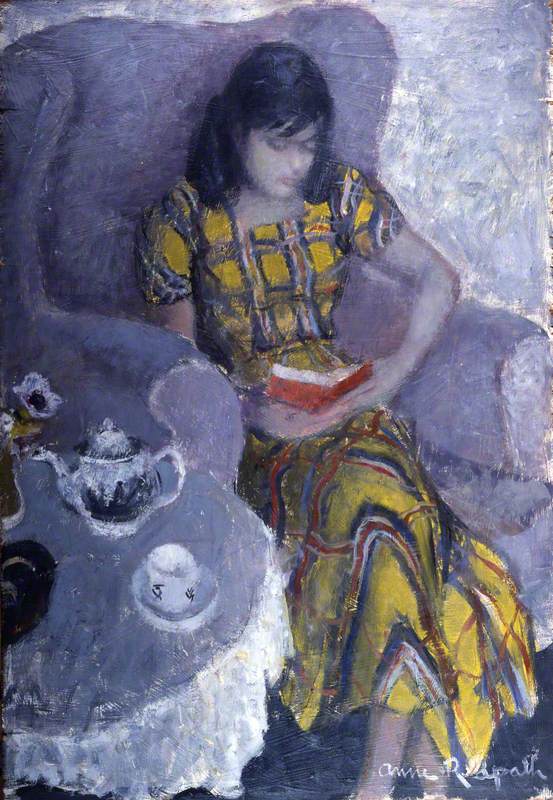

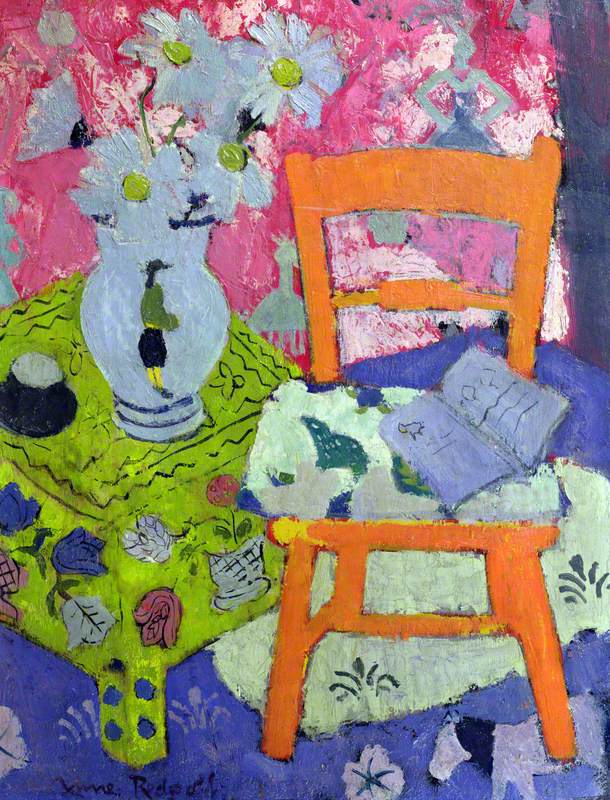

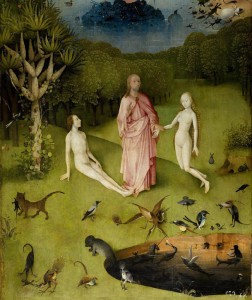

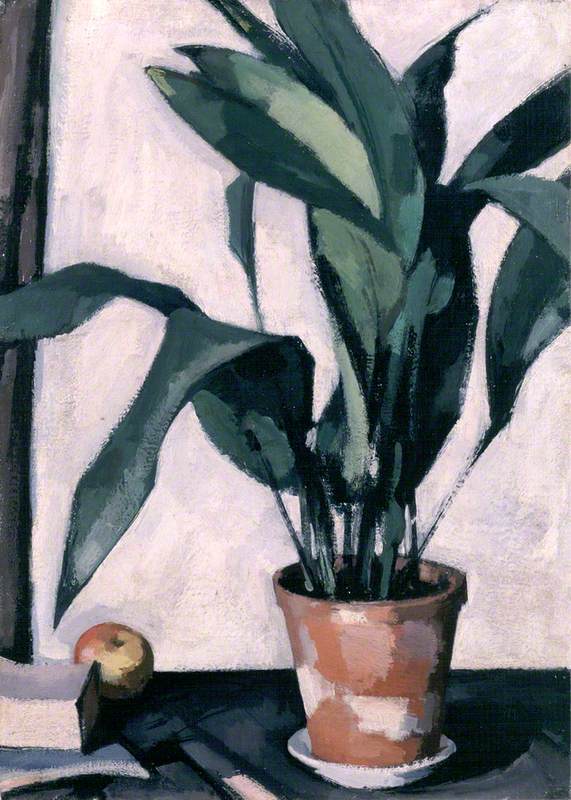

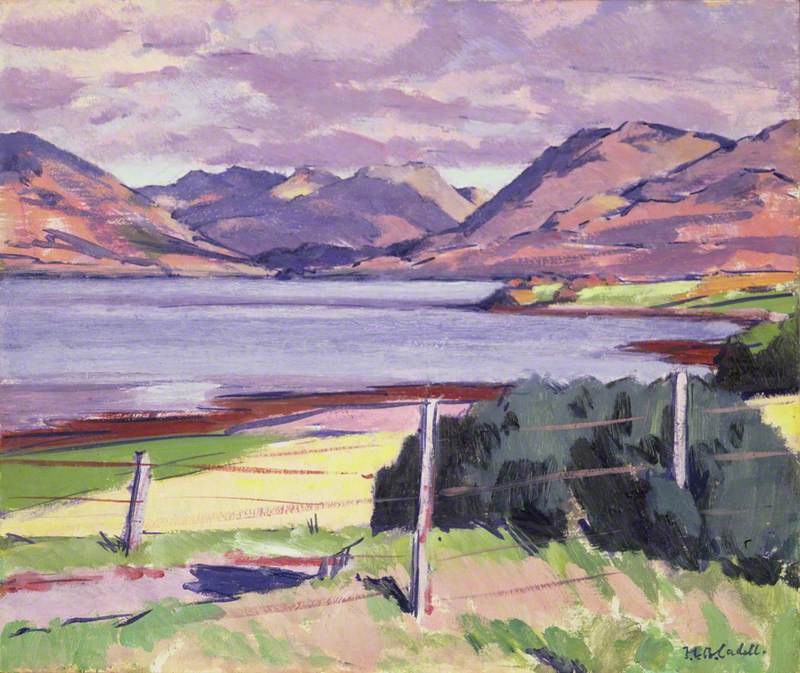

It is impossible to look at one of Redpath's best-known paintings of an interior with domestic objects, the subject she made her own –The Indian Rug (Red Slippers) of c.1942 – and not think of Henri Matisse and his Scottish disciples: Francis Cadell and Samuel Peploe.

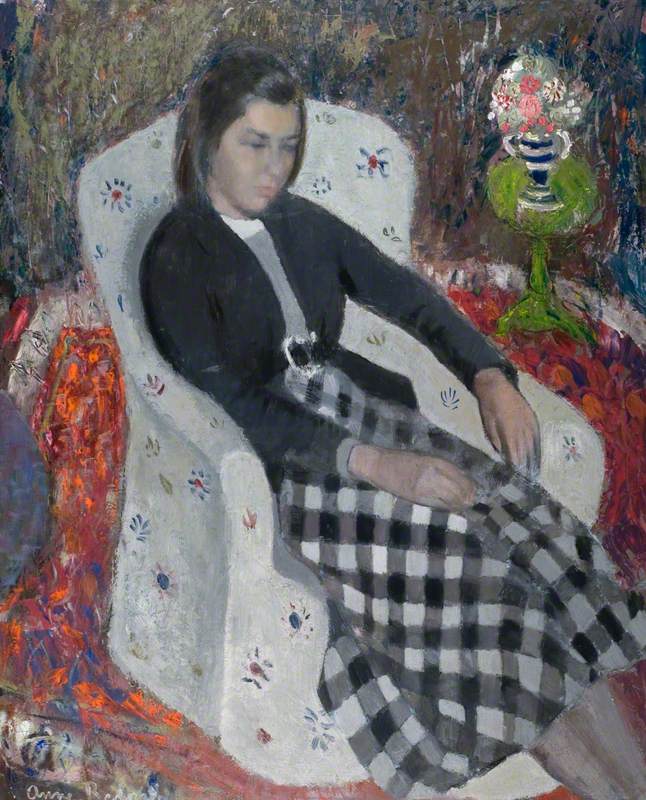

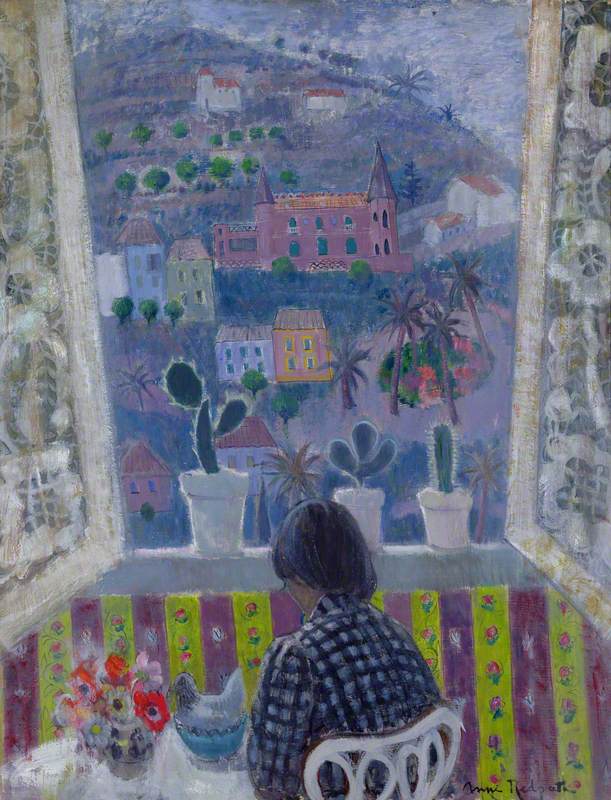

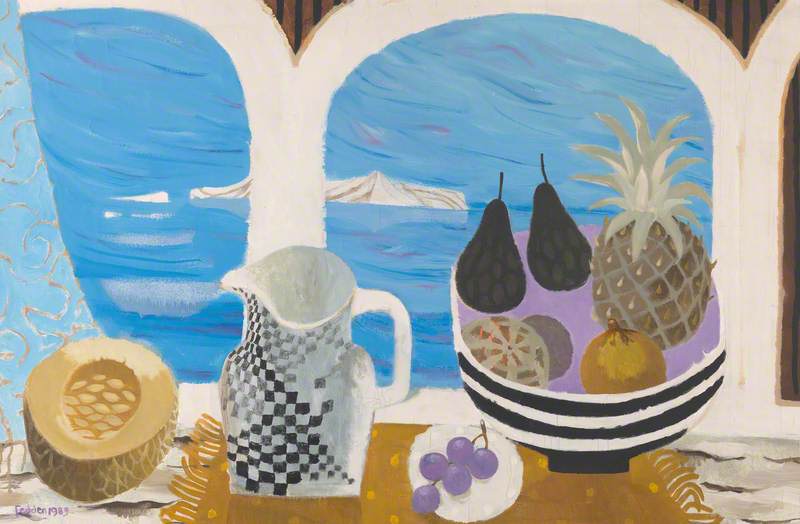

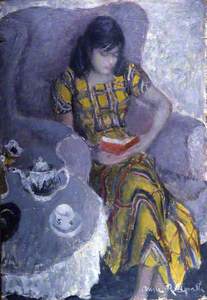

Her Window at Menton, which was exhibited in 1950 (and which Redpath liked so much that she sold it only unwillingly) pays homage to the work of Pierre Bonnard, with its lace hung windows opening out onto a gentle French landscape, and the female sitter wearing a checked garment, the type of setting and patterned fabric that often appeared in paintings by the French Intimiste.

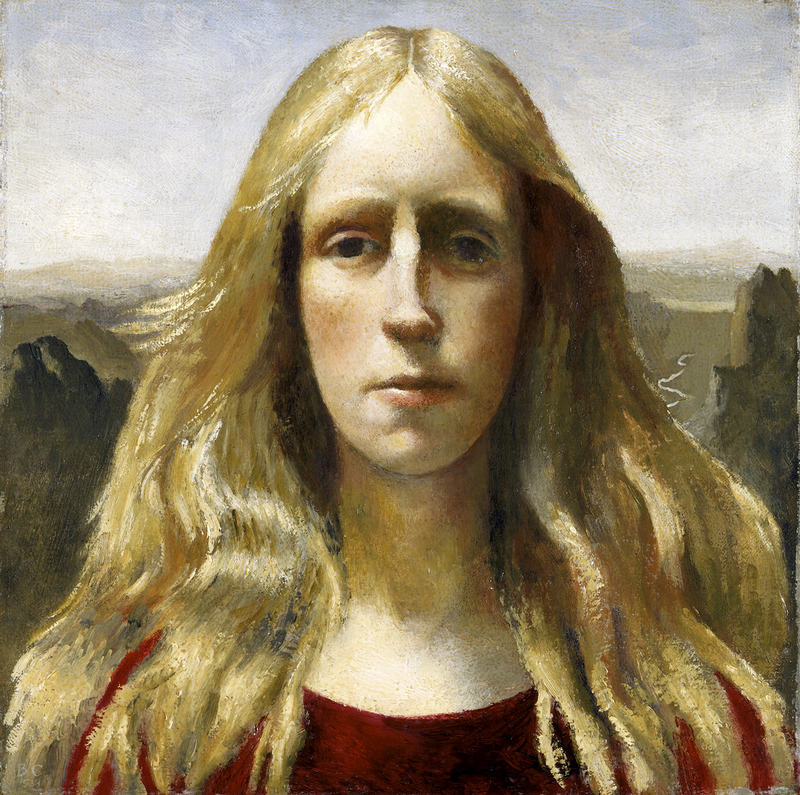

Redpath, who was born in Scotland, trained at Edinburgh College of Art. Among her earliest surviving paintings is a study of a life model of 1918 – a standard student exercise, though her work is unusual, strikingly confident and modern in its starkness.

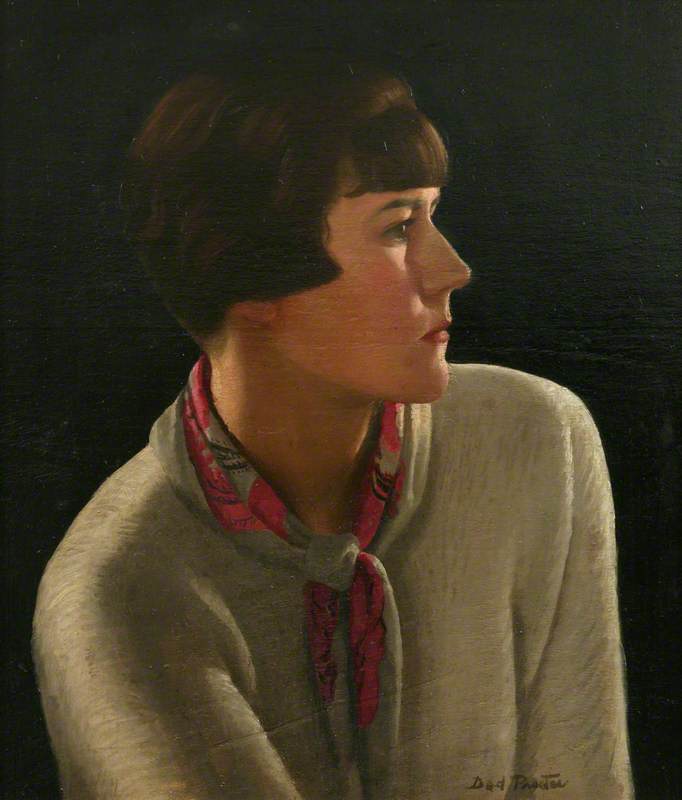

A portrait of a friend she made during her studies, Girl in a Red Cloak of c.1920, has a flat, stylised symbolism reminiscent of the work of Glasgow School, which they had developed from their own studies of French modernism.

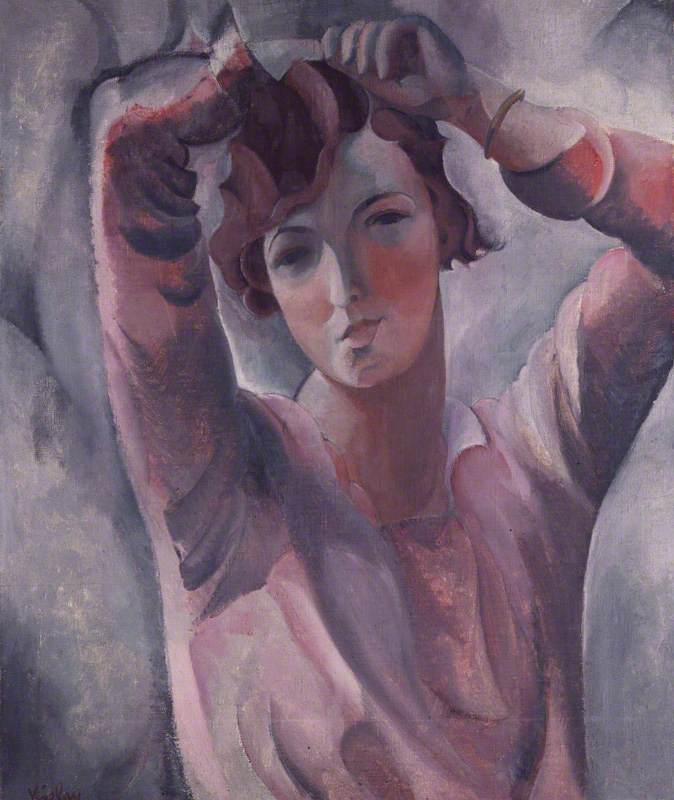

Art education in the two major Scottish cities was progressive: it looked to international developments and allowed women to study, and the country became home to a number of gifted women painters who were born in the late nineteenth to early-twentieth century, including Joan Eardley (1921–1963) and Elizabeth Blackadder (b.1931). There are similarities between Blackadder's compositionally experimental still lifes, with their relish of colour, and Redpath's work.

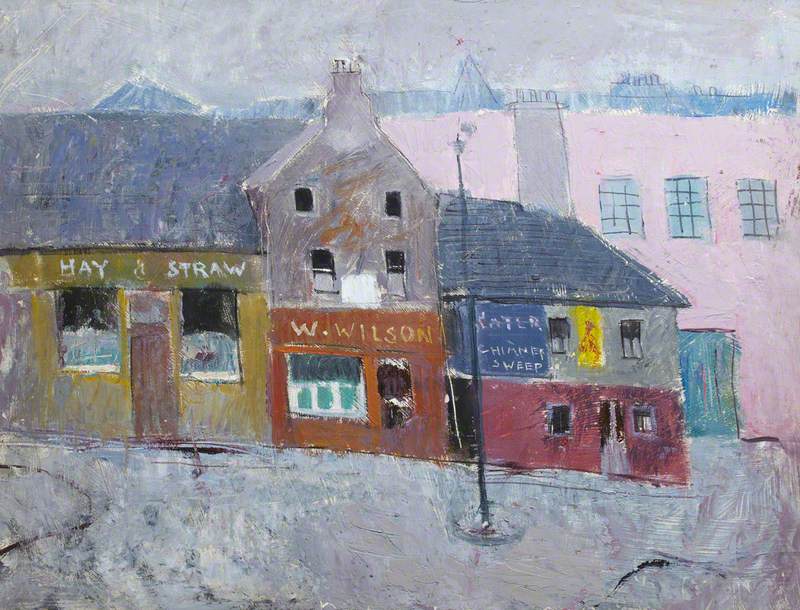

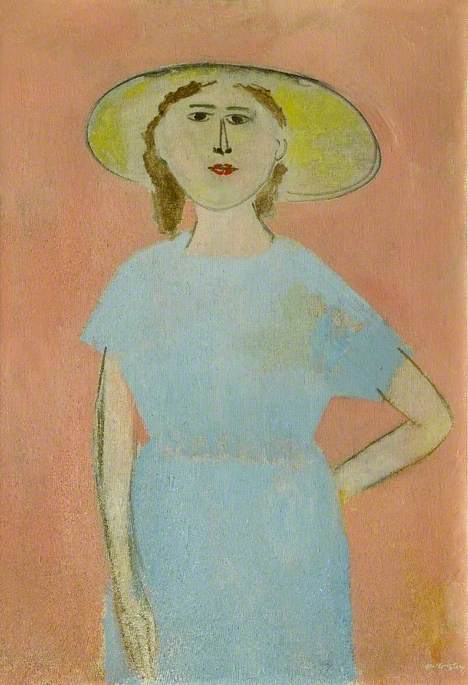

Like Eardley, Redpath painted scenes of fishing villages and boats, though hers were sometimes made in France, where she lived between 1930 and 1934, or on travels in Europe, rather than centred on the Scottish coast. And though Redpath did not share Eardley's interest in stark urban scenes – slums and street kids against graffiti-scrawled walls – there is an element of down-at-heel realism, albeit exquisitely painted, in some of Redpath's mid-century portraits.

Her painting of Lindsay Michie, shown casually slumped in a chair and tieless, with one hand stuffed in his pocket and Brylcreemed hair, anticipates something of the attitude of John Osborne's anti-hero, Jimmy Porter, in the play Look Back in Anger (1956). Although the suggestion of humour in the face is more akin to that other 'Lucky' Jim in Kingsley Amis's novel (1954).

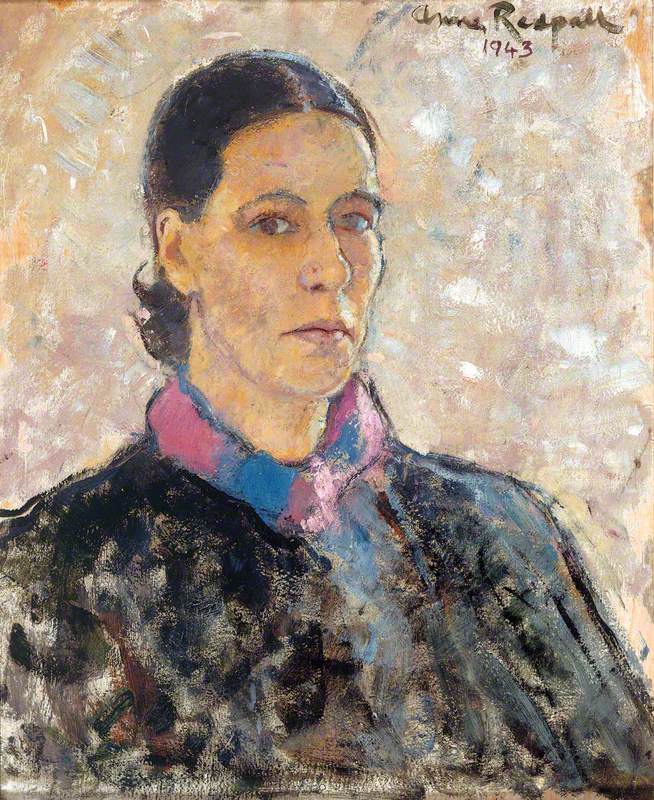

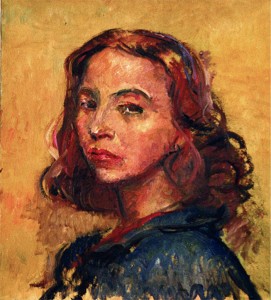

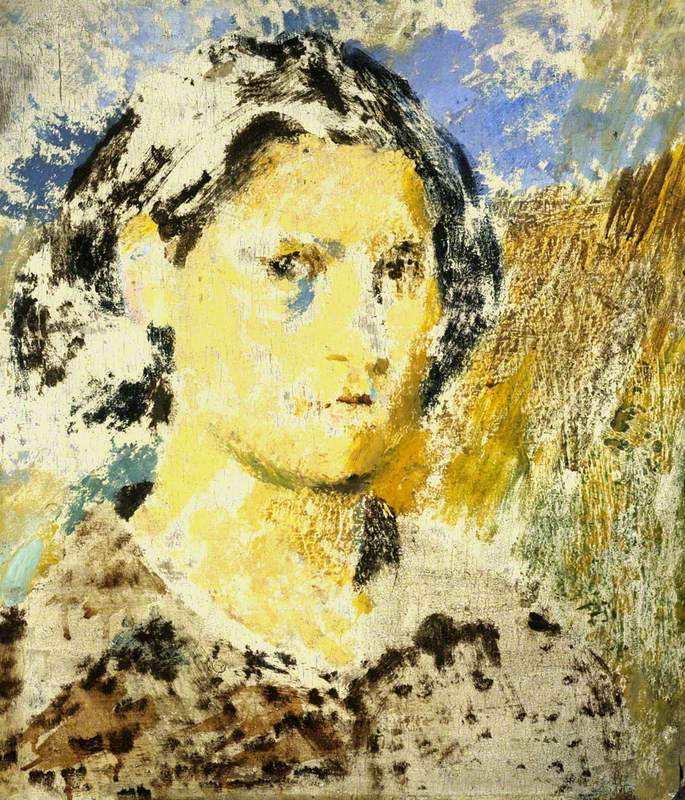

Commissioned by the collector Ruth Borchard in 1964 to paint herself, Redpath sent a self-portrait she had completed in 1943 which balances severity – the hair pulled back, the mouth unsmiling, the gaze level and steady – with the most gorgeously nuanced colour: the flickering dabs of paint are close toned but with anarchic touches of strong contrasts, the dark clothes the artist wears set off by a pink and blue scarf.

It is a statement of serious intent, but makes it clear that seriousness can be allied with, and is not cancelled out by, an artist's joy in colour. A woman working with a rich palette (just as one who painted flowers, or interiors, or made portraits of women) ran the risk of being dismissed as second rate, something her male colleagues never faced, no matter how overtly decorative their painting or 'feminine' their subject matter.

A year after she painted her self-portrait, Redpath was made President of the Scottish Society of Women Artists. In 1952 she became the first woman ever elected to the Royal Scottish Academy, and in 1960 she became the first woman to be made an Associate of the Royal Academy since the Second World War. Though later in life, Redpath was to dismiss the need for women to have special attention and be exhibited separately – she had become a trailblazer for women artists herself.

She shared this refusal of the category 'woman artist' with some other successful women artists of her time (and since). As a daughter of parents who had to be persuaded to let her go to art school (only allowing her to do so if she also agreed to train as a teacher) and a wife (of the architect James Michie) and mother who had had to give up painting while her three children were small, Redpath had faced setbacks particular to her gender.

Despite her success, her work had been dismissed by some critics as 'sugary' and naive, marred by a 'feminine' sense of colour. Ruth Borchard's collection of self-portraits, which Redpath's work joined, included only five women among the one hundred artists.

Perhaps Redpath believed that the achievements of her career, not least building and sustaining one, might be diminished by being put in such a category? Her refusal of it, then, was born of a desire to distance herself from anything that might endanger a hard-won reputation.

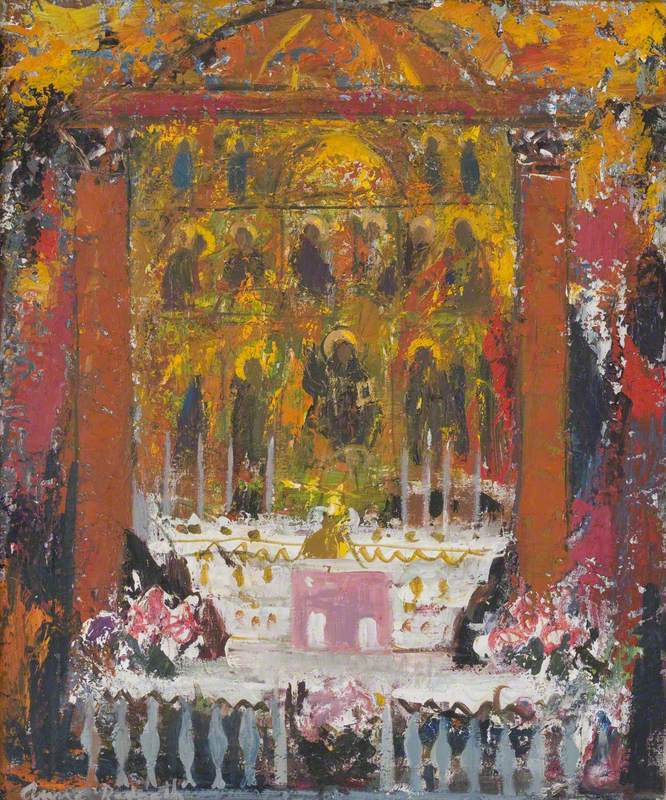

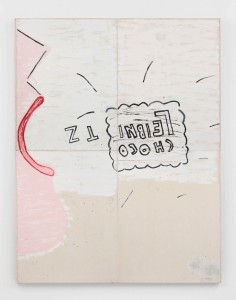

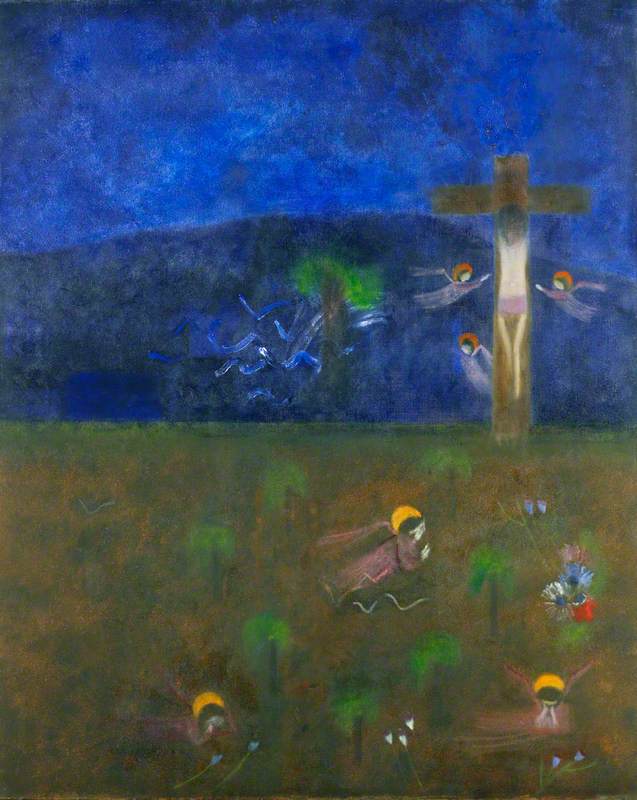

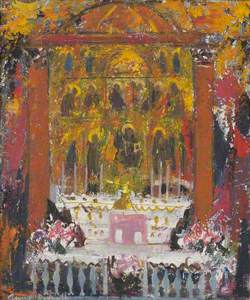

Redpath's late work was marked by an interest in religious objects and places, altars and chapels, and new developments in technique. Now she began to push the medium until the subject, though never abandoned completely, was almost lost.

She was interested in emerging avant-garde painters, especially those taking risks with the physical character of paint and ground, working with extremes of texture and variations in thickness and fluidity – Jackson Pollock and Antoni Tàpies among them – though Redpath never moved into pure abstraction herself.

In Madonna from Mexico (c.1963) glorious pinks and reds encrust the tinselly, doll-like figure and threaten to engulf her.

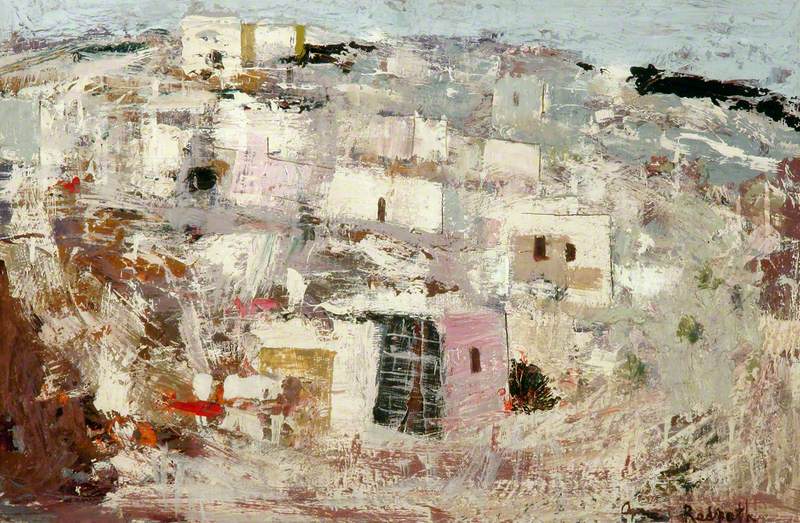

While in Cliffside, Portugal, painted c.1965, the last year of Redpath's life, technique dominates to the extent that the landscape becomes nearly illegible, but as a result, the immediacy of the experience of the world is heightened, the eye held and thrilled.

Alicia Foster, curator