'LISTEN: I have found the home of my heart. I could not eat: I could not think straight any more; so I came to this solitary place and lay in the sun.' – Brenda Chamberlain, Tide-Race

When Brenda Chamberlain moved to Bardsey Island in 1947, she knew it was a life-changing decision. The artist was no stranger to isolated living – she had called the small village of Llanllechid in Snowdonia home since 1936 – but on Bardsey, she would be at an even greater remove. The island, whose Welsh name is Ynys Enlli or 'Island of the Currents', sits alone in the Irish Sea off the tip of the Llyn peninsula in Gwynedd. The crossing was frequently rough and dangerous, and it was not unusual for islanders to be cut off from the mainland for days. But she felt called there, enthralled by its uncompromising beauty and the promise of a fresh start. She stayed 14 years, immortalising island life in drawings, paintings and a novel, Tide-Race, published in 1962. From this lonely outpost at the edge of Wales, she made her name.

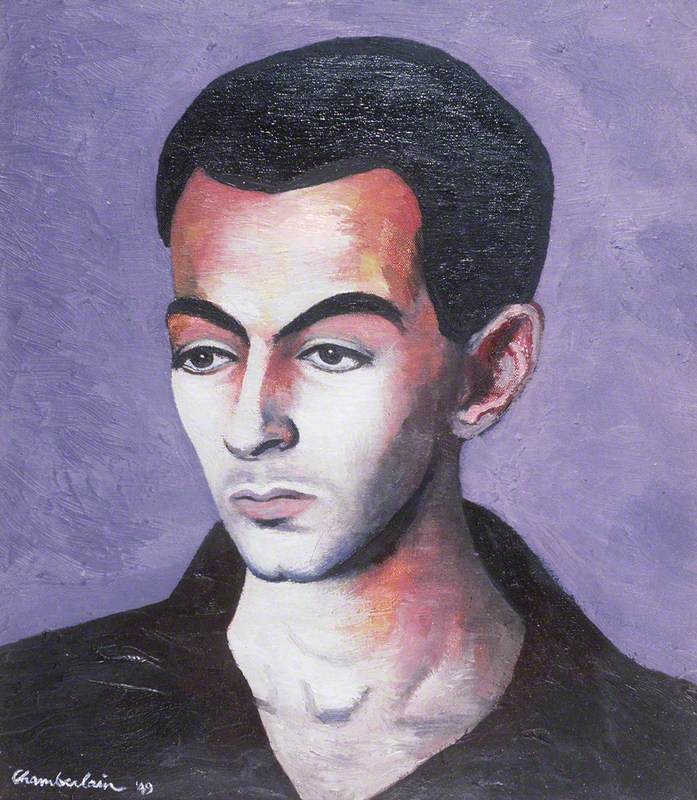

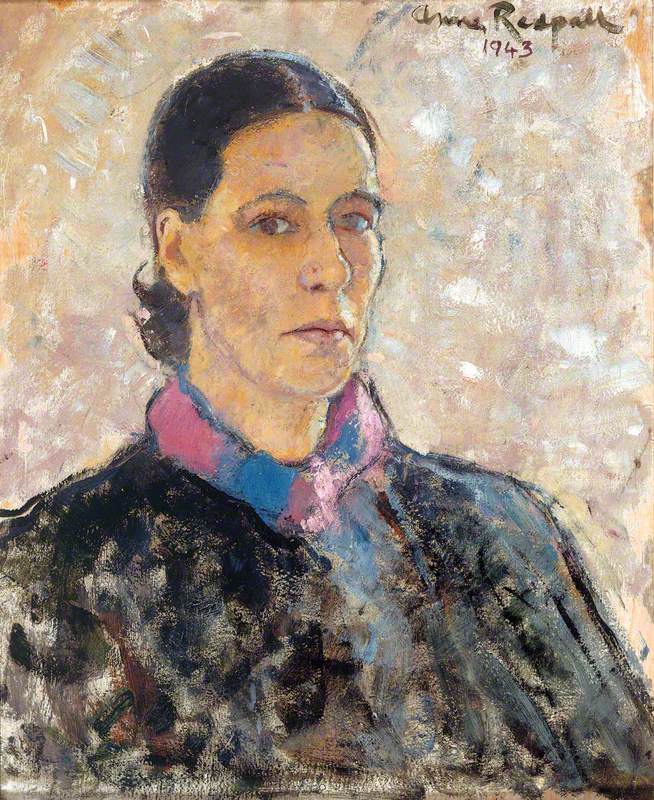

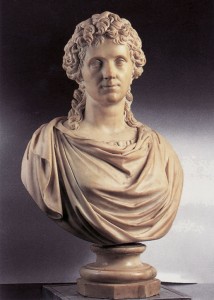

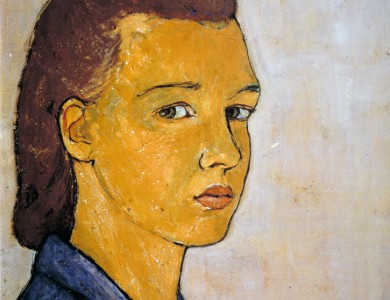

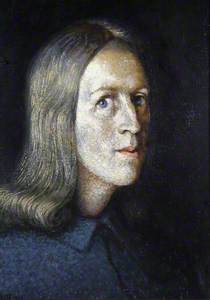

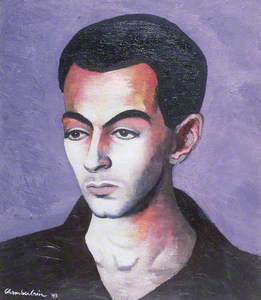

Self Portrait on Garnedd Dafydd

1938

Brenda Chamberlain (1912–1971)

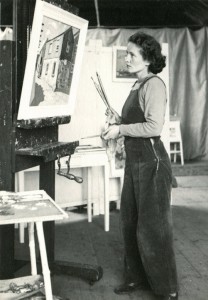

Born in Bangor in 1912, Chamberlain developed dual passions for writing and fine art as a young girl and studied the latter at London's Royal Academy Schools from 1933 to 1936. On graduating, she returned to Wales with her husband, John Petts, and settled in the mountains in search of a quiet creative life. Her arresting Self-portrait on Garnedd Dafydd (1938) gives a sense of her burgeoning talents. The artist faces the viewer squarely, head held high, long hair blown back slightly from her face. It’s a masterly portrait, carefully yet confidently modelled, with a sense of contained energy. In the background, the valley falls away, its distant river glinting in the sun – but the focus is on Chamberlain. She was drawn to dramatic places, but it is her personal experiences within them that come to the fore in her art.

At Llanllechid, Chamberlain and Petts established the Caseg Press. She published her poems in the Caseg Broadsheets, launched with the poet Alun Lewis, and produced powerful woodcuts and linocuts to illustrate them. But she painted little, and the advent of war, followed by her separation from Petts in 1944, further disrupted her work. It was only on Bardsey that she picked up her brushes again in earnest.

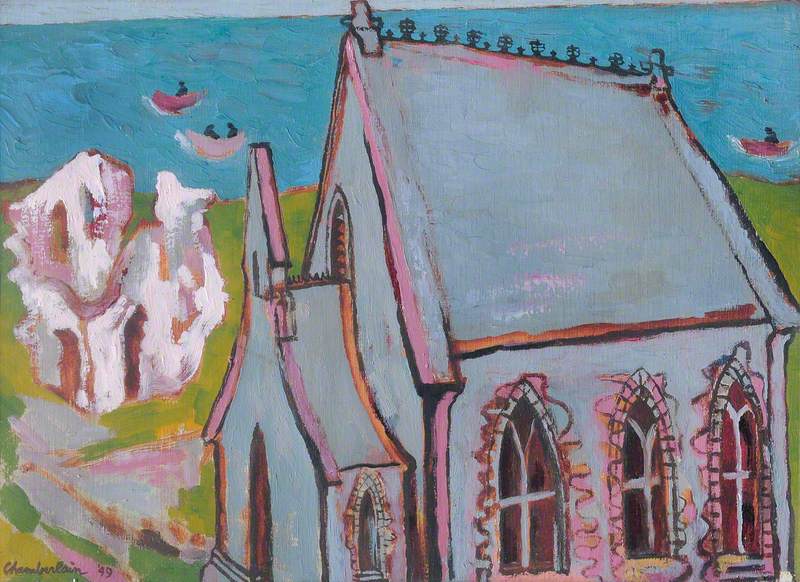

Chapel and Ruined Abbey, Bardsey, from 1949, reveals some of the elements that attracted her to the island. Firstly, the colours: bright swathes of blue, green and yellow are countered by the moody mauve-grey of the chapel and the white flash of the ruins, and the composition is laced with veins of pink and red paint. Chamberlain was routinely astounded by the intense colours in Bardsey's outwardly austere landscape. After introducing the abbey in Tide-Race, for example, she goes on to describe:

'A rock shore; cliffs of mussel-blue shell. Wine-red, icy pink, pure white, yellow and green. The surf creamed at the foot of the coloured walls. Colours evoked images, images evoked words. Wall of jasper, tower of quartzite. How can a common seacliff be a wall of jasper?'

Inseparable from Chamberlain's appreciation of the landscape was her fascination with its history. St Mary's Abbey dates back to the sixth century; the bones of 20,000 saints are reputed to be buried on the island and it has been a site of pilgrimage for centuries. Chamberlain felt connected to these ancient visitors and wove her personal myth in with theirs. 'The monastery stones... stood as a symbol of the human spirit, not only of religious faith but of escape as well.'

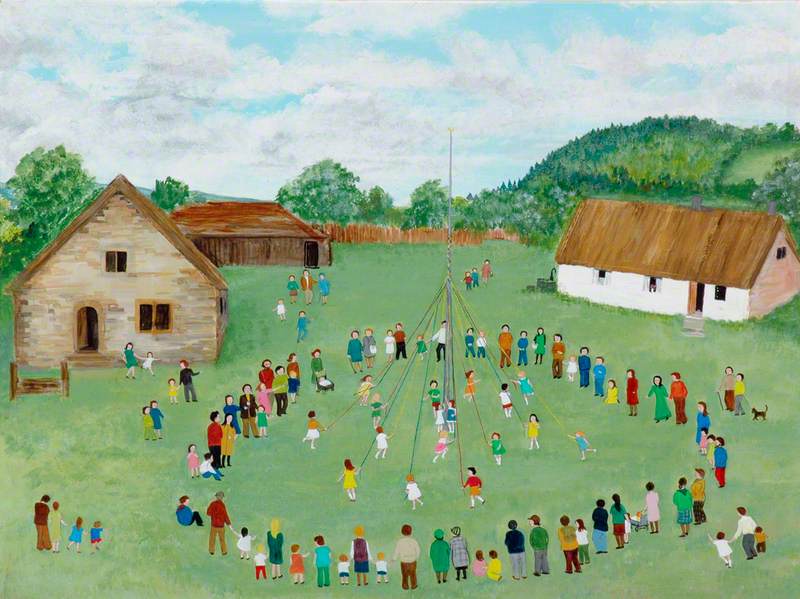

But life on Bardsey was no fairytale. Chamberlain and Jean Van der Bijl (her partner there) lived off the land, fishing, farming and scavenging cliff-eggs, and she fitted her painting around laborious daily routines. The local community was small, close-knit, and strung with social tensions that Chamberlain relates colourfully in Tide-Race (much to her neighbours' chagrin; it was made clear after the book's publication that she would not be welcome back). But for all these foibles, she felt very much part of island life. Her paintings are more symbolic in tone, commemorating the toil and dignity of fishing communities.

In The Fishermen's Return (1949) she depicts two men at ease on a languid sea, their catch at their feet, another vessel following behind. Chamberlain makes use of the block colours and dark outlines she practised in her printmaking days, and the figures have archetypal features – oval faces and almond eyes – that became characteristic of her work. She makes good use of texture: the grey-blue sea comes alive through dappled brushwork, while a green cliff looms pale and flat on the horizon in an atmospheric haze.

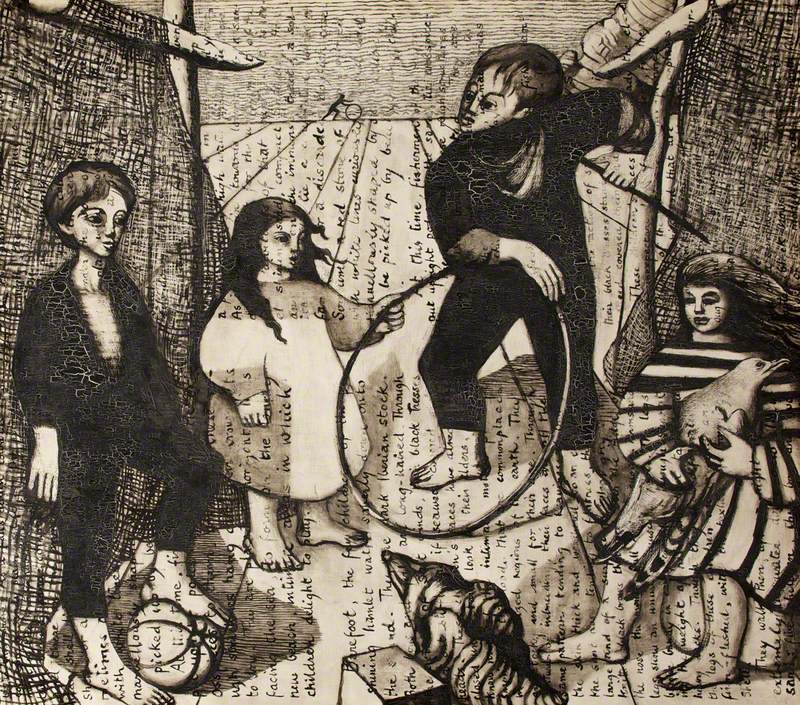

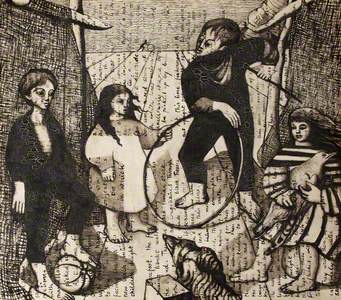

In Children on the Seashore (1950) Chamberlain paints four young islanders on a white sandy beach, and a fifth playmate rolling a hoop in the distance. She wrote this scene before she painted it, transcribing the words onto the canvas in vertical lines of text: 'These young children are of dark Iberian stock', she observes. 'Through the action of winds, their black hair stands out stiffly, as if some kind of seaweed covered their heads. Their faces have already the closed unexpectant look of their elders, for they know none of the small intimate delights and surprises of childhood that are commonplace in more civilised and mother-protected regions of the earth.'

There is no sandy beach on Bardsey; in her paintings and her writing, Chamberlain frequently combined fact and fiction to express the emotions and associations that events inspired in her.

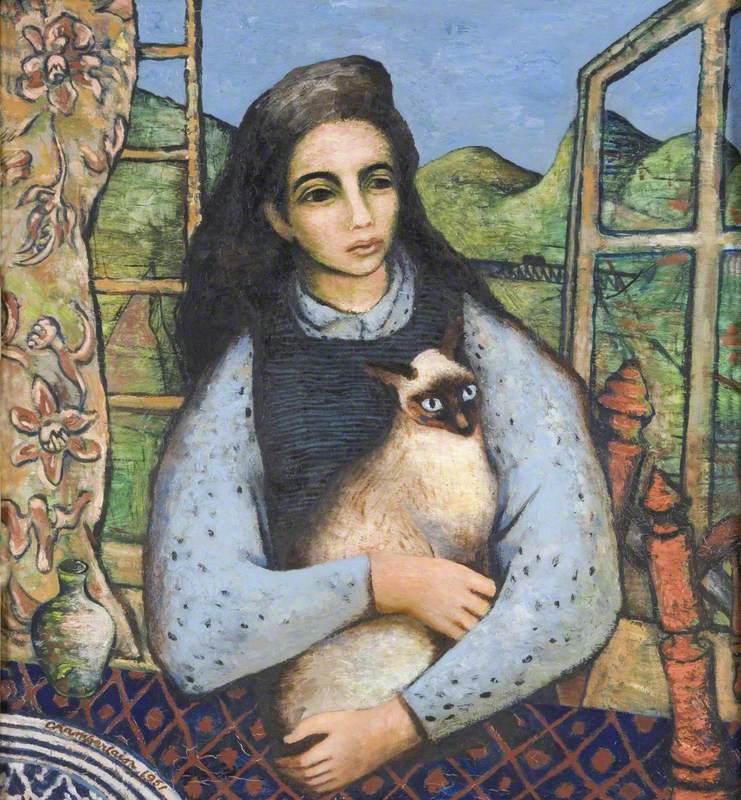

As Chamberlain's confidence increased, so did public recognition. In 1951, she won the Gold Medal for Fine Art in the National Eisteddfod, for Girl with a Siamese Cat (1951). (She would win again two years later.) The enigmatic work depicts one of Chamberlain's neighbours at a table, cradling the artist's pet. Both gaze at a point outside the frame, distracted, while behind them a window opens onto a hilly green landscape and clear sky. The painting is packed with colour, pattern and texture, carefully modulated to form a cohesive whole.

Over time, life on Bardsey had the unexpected effect of reconnecting Chamberlain with the world. In 1950 she had her first solo show at Gimpel Fils in London, reigniting her interest in avant-garde art. She frequently spent spells off the island and in 1951 visited Ménerbes, France, where she delighted in the sunny surroundings and met fellow artist Dora Maar. On her return to Wales, she painted a reflective portrait: Dora Maar – Interieur Provencal (1952).

Maar's pale figure seems protected by the armchair in which she sits, and bright domestic details – furniture, wallpaper and a bowl of glossy aubergines – animate the otherwise quiet scene.

Maar lived reclusively in Ménerbes after the breakdown of her relationship with Picasso. Perhaps Chamberlain felt some kinship, for she too recognised a need for isolation. 'I came back to my prison on the sea rock,' she recalled after the trip, 'everything put from me but the ambition to succeed as an artist. It is only in voluntary imprisonment that I can bring out the painful fruits of experience.'

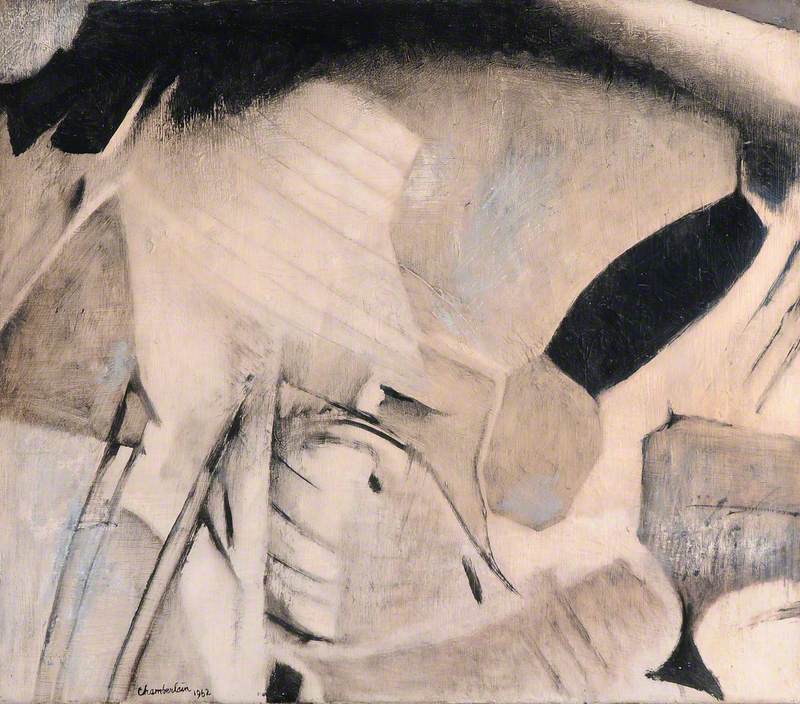

At the end of the decade, Chamberlain's creative focus turned back to the island as she prepared to publish Tide-Race. In particular, she dwelt on the power of the sea – its immense influence over her island life, and its capacity for destruction. 'I have lived for years in a world of salt caves, of clean-picked bones and smooth pebbles', she acknowledged. 'I began to paint salt-water drowned man, never completely lost to view.'

Man Rock (1962) embodies the powerful new style that emerged when she let the sea seep into her art. Painted in stony greys and browns, and pocked with shadowy hollows, it simultaneously suggests a torso, a lump of stone, and a map of an island edged with rocks and surrounded by frothing seas. 'These are anything but abstract paintings', Chamberlain insisted. 'They are ledges of encrusted rock, an armoured leg braced in silt, the loins of a body changed gradually into a stone bridge, a wounded torso, flood-tide rising up the walls of a cave into the far corners of which a storm has embedded bones'.

These paintings were the culmination of Chamberlain's time on Bardsey; even as she worked on them she sensed it was time to move on. In 1962, she held a solo exhibition to coincide with the publication of Tide-Race, before travelling to the Mediterranean where she discovered the sun-bleached island of Hydra. Once again, she felt the siren call of an island home, and relocated, staying five years until the coup of 1967 forced her unhappy return to Bangor.

'In 1962, I had been forced to the realisation that life on Bardsey was coming to an end', Chamberlain once reminisced, 'but, these had been formative years, and I knew that the island was in me for life and that wherever fate was to lead me thereafter, I should never lose the reality I had gained from it.'

Maggie Gray, art historian and writer