There have been pictorial representations of the Magi – the three wise men or kings who visited Jesus as a baby – from as early as at least the sixth century AD. Their depiction over this vast period of time has been anything but consistent. However, let us deal with the consistencies first – and there are many.

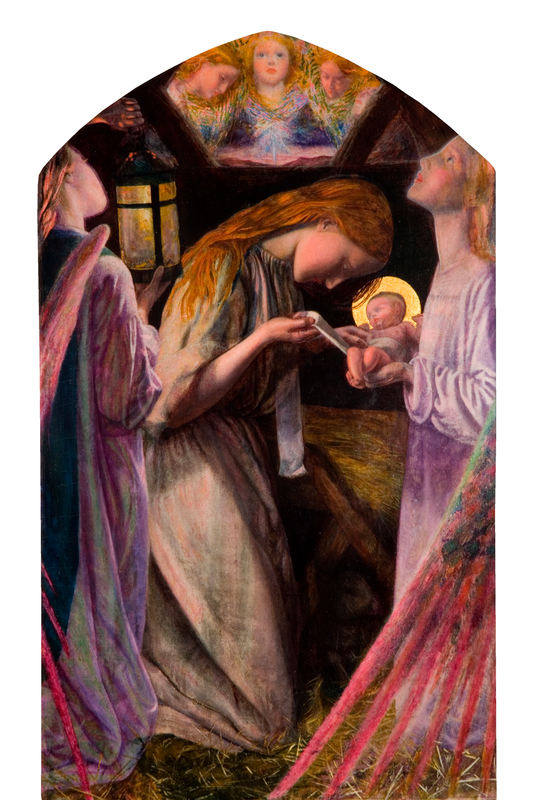

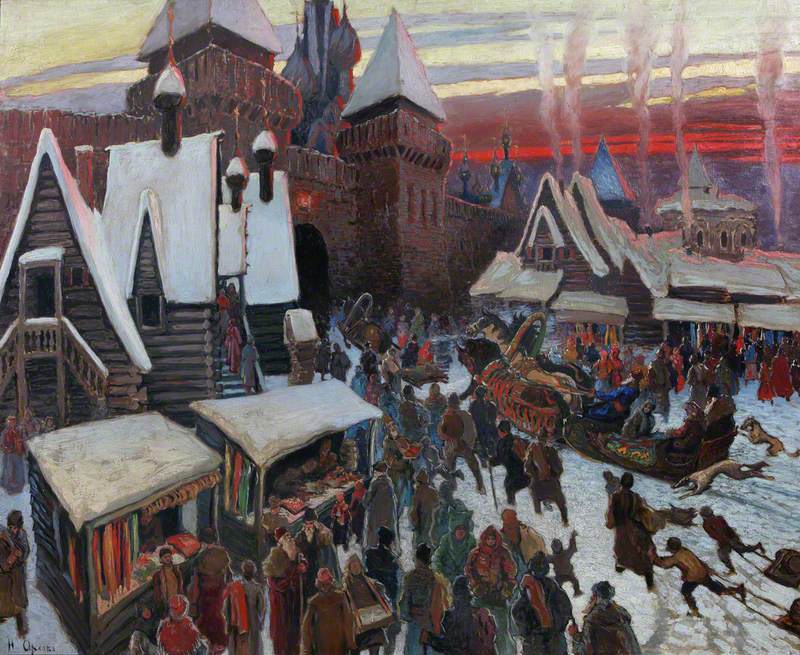

The most obvious is clearly the number of three Magi/kings who bring the gifts of gold, frankincense and myrrh. The other constant is the Holy Family upon which the entire story rests. But there are some aspects that may at first seem to be consistent then turn out not to be on close examination of the images. For example, many images of this story feature the Holy Family – Jesus, Mary and Joseph – in humble surroundings.

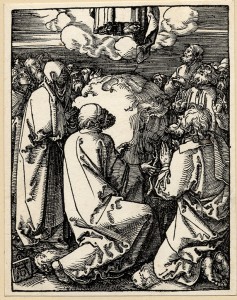

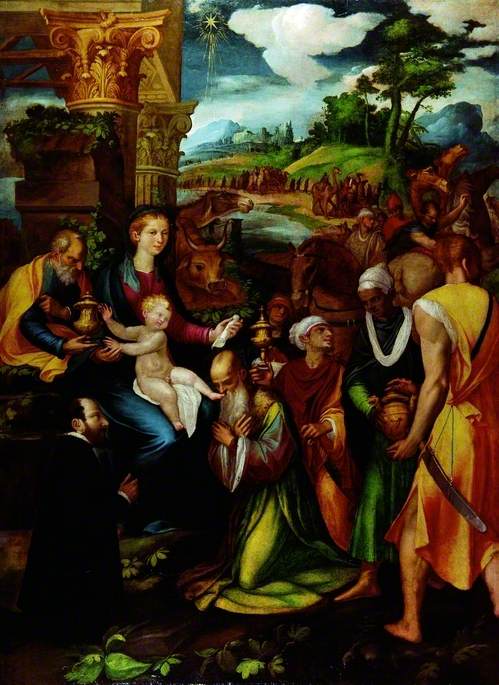

The Adoration of the Magi

late 1560s

Jacopo Bassano the elder (c.1510–1592)

In Jacopo Bassano’s The Adoration of the Magi of the late 1560s (at The Barber Institute of Fine Arts) we alight on a lean-to construction that seems to have been put together against the ruin of a classical building. The kings arrive with their retinue and pay homage to the newborn Christ child.

In Gerard David’s c.1515 Adoration of the Kings (at The National Gallery) there is once again a ruin, this time what looks to be a medieval castle, and in Sebastiano Ricci’s c.1726 Adoration of the Magi (at the Courtauld Gallery) we return to a lean-to structure (just visible in the upper left of the picture) and what looks to be a Roman arch. Ricci repeats the classical motif in another Adoration painting (at Lamport Hall), this time with classical columns in the centre of the image.

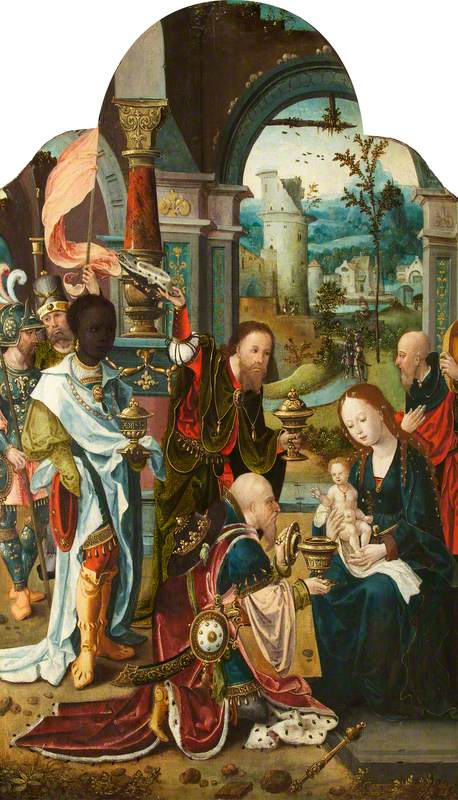

Adoration of the Magi

c.1500–1510

Michelangelo di Pietro Membrini (active 1489–1521)

These lean-to/classical combinations appear in so many Adoration images across the centuries – including Peter Paul Rubens' oil sketch of c.1633 at the Wallace Collection, and Michelangelo di Pietro’s c.1500–1510 Adoration of the Magi at the Courtauld Gallery – that they cannot be merely coincidental. The meaning of these lean-tos and classical ruins seem to clearly point towards humility and the triumph of the new world order (represented by the Holy Family) over the crumbling old world order (the Roman world, represented by classical ruins).

But even this seemingly standard aspect is in itself inconsistent – other artists choose not to use the iconography of classical ruins. For example, Bartolomé Esteban Murillo, in his Adoration of 1660–1665 at the Dulwich Picture Gallery, instead opts just for the humility of a cave with seemingly no sign of even a lean-to structure.

The Adoration of the Magi

about 1433-4

Zanobi Strozzi (1412–1468) (attributed to)

An adoration painting of 1433–1434, attributed to Zanobi Strozzi (at the National Gallery), also dispenses with the classical ruin, this time setting the scene in a humble shed-like structure.

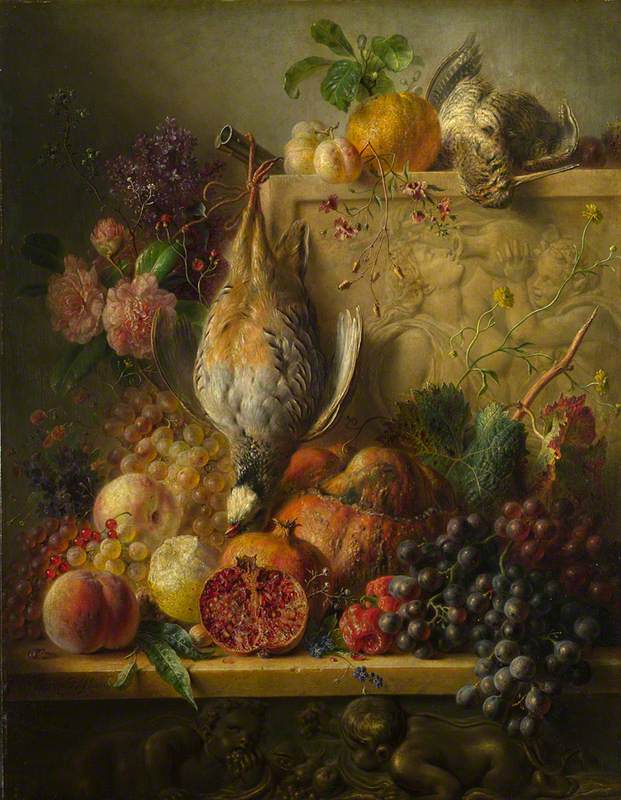

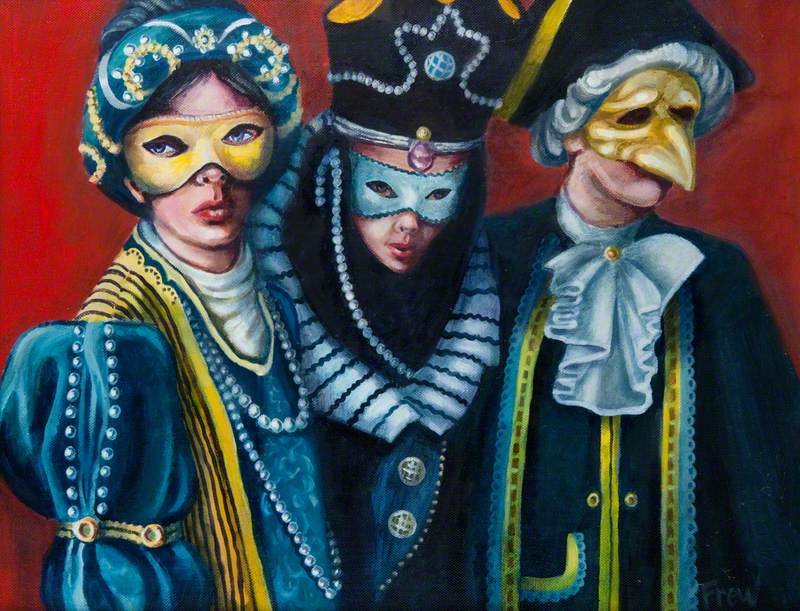

However, what is consistent across centuries of depictions are the splendid sumptuous clothes worn by the Magi. If not resplendent in the decorative effects of their garments as we see in Strozzi's Adoration, they are made with beautiful fabrics as we see in Bassano’s depiction.

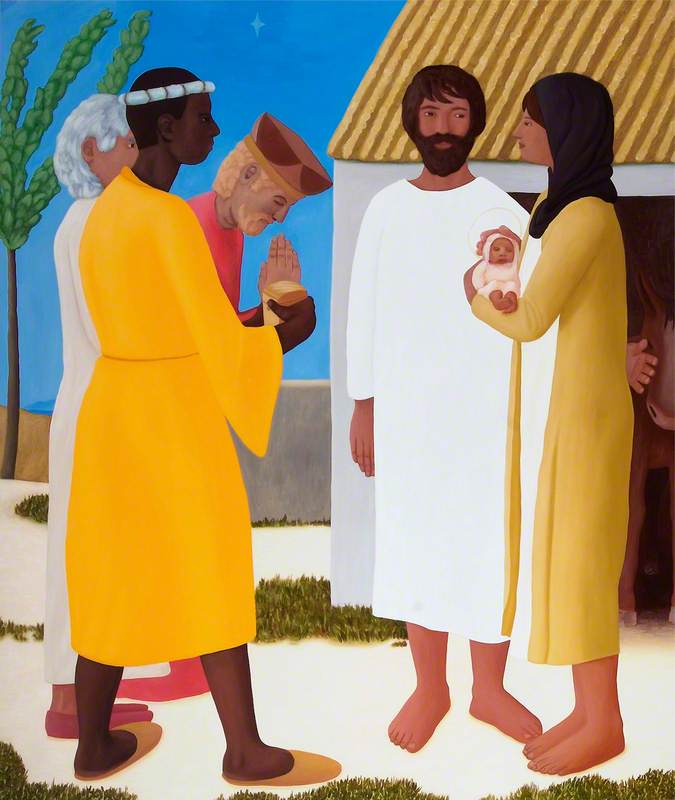

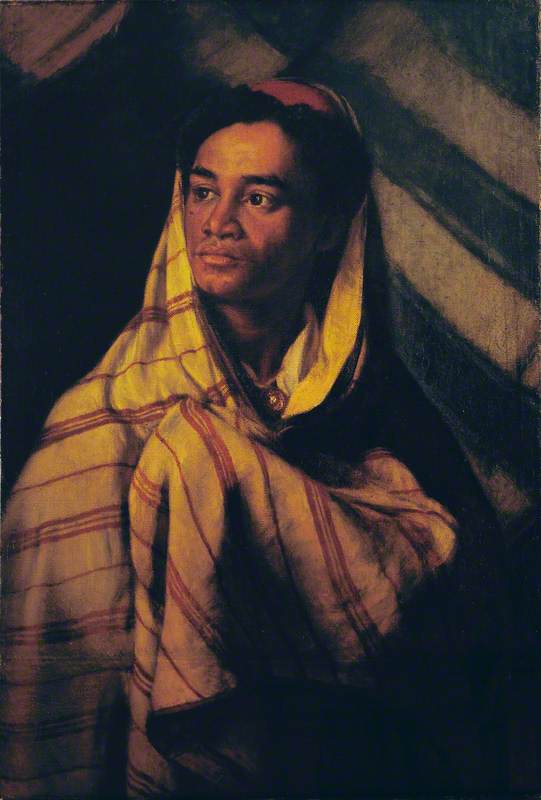

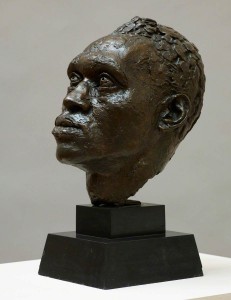

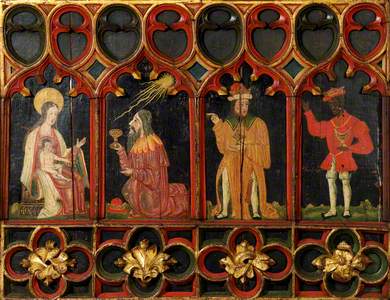

According to legend the Magi/kings went by the names of Caspar, Melchior and Balthasar. Legend also tells us that there is an older king, the youngest king, and – of course – a black king.

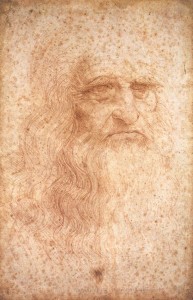

In line with customs of respect, the eldest king is always first to present his gift of gold and is often given the name of Caspar. Artists familiar with this custom use the iconography of grey hair, a beard or both to depict old age (a convention which still holds true today).

The Adoration of the Magi

c.1503–1510

Master of the Glasgow Adoration (active c.1490–1520)

In the case of the youngest king, a lack of facial hair points towards youth, and this king is usually associated with the name Melchior and the gift of frankincense. However, youthfulness, seen in the work of the Master of the Glasgow Adoration, can sometimes lead to Melchior being mistaken for a woman or girl.

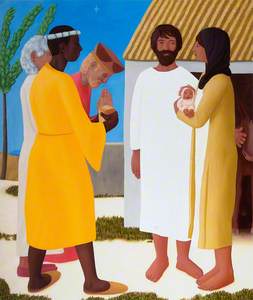

The Adoration of the Child Jesus

probably 1480s

Cosimo Rosselli (1439–1507)

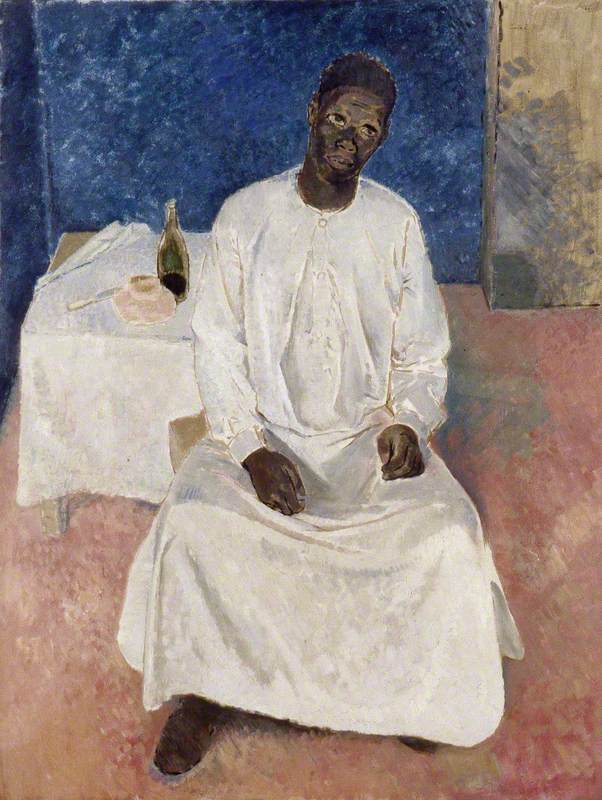

Our route to identifying the next king should be easy, because not only do we have the process of elimination, but also the third king, Balthasar, is black. However, as we can see from our examples this is also an inconsistency – nobody has informed Zanobi Strozzi or Cosimo Rosselli that such a person should be included. Indeed, the only early sixteenth-century artist in our examples that received the memo is Gerard David.

What can clearly be established at this point is that not every artist across the ages has been singing from the same song sheet, and this must be due in large part to the ambiguity of texts purporting to tell this story. For example, one of the pieces of biblical text commonly associated with this story

When they had heard the King, they departed; and lo, the star, which they saw in the east, went before them, till it came and stood over where the young child was. When they saw the star, they rejoiced with exceeding great joy... they presented unto him; gifts, gold, and frankincense, and myrrh.

This text seems to set the scene that most of us are familiar

The Adoration of the Magi with a Donor

c.1546–1550

Vincenzo da Pavia (c.1495/1500–1557)

Yet by the sixteenth

The Adoration of the Magi with Saint Margaret and a Nun

16th C

Netherlandish School

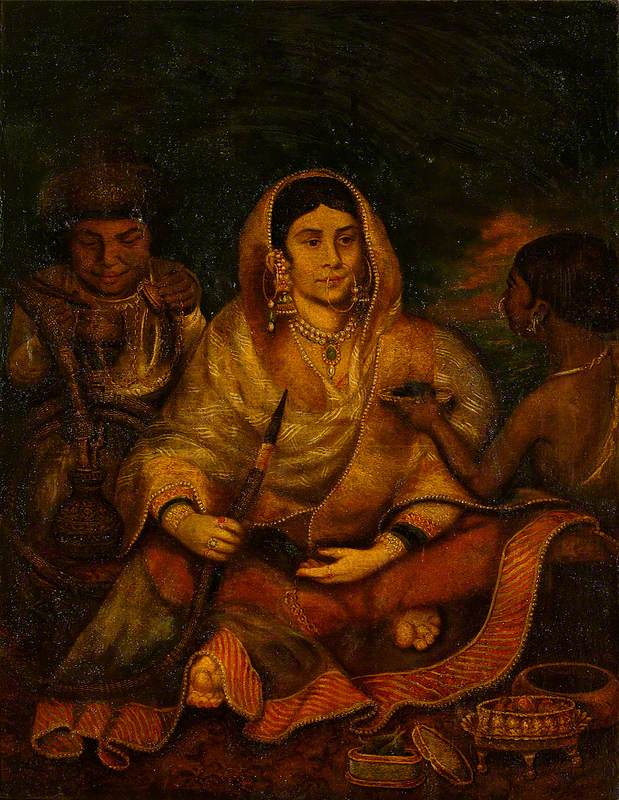

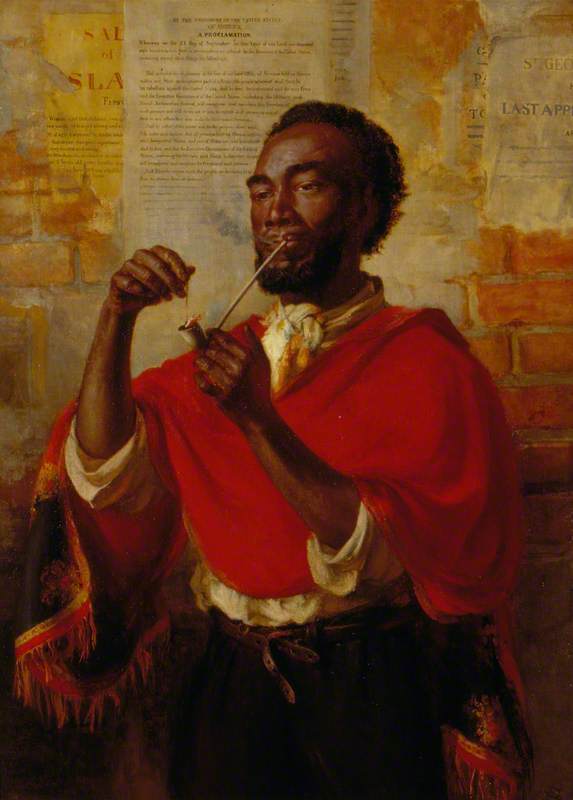

Another of the factors governing the inconsistency of the black king in depictions is artists’ lack of knowledge of actual black people in mid to late fifteenth-century Europe. Even when they are depicted, we are only given partial views, such as the Bassano and the Ricci, thus avoiding the tricky rendition of a physiognomy the artist has no knowledge of – or, in the case of the Gerard David, a European physiognomy with a darker shade. The European perspective on the black king would be given much credence by the writings of Saint Augustine of Hippo (354–430 AD) who was the first to alight on the already existing the idea of a black king (and thus in his opinion Ethiopians) as a symbol of the universality of the Christian faith.

The idea that the Magi were from distant lands and they were kings probably came about via the writings of the Christian theologian Tertullian (c.160–c.230 AD), who in the year 200 AD was the first to infer that magi in distant lands were more or less seen as kings. It is left to the third-century theologian Origen (d.254 AD) to say that there were three of them. Although this is also not mentioned in the Bible it seems a reasonable assumption as three gifts are mentioned – gold representing homage to Christ’s kingship, frankincense representing homage to Christ’s divinity, and myrrh, used in embalming, to foreshadow Christ’s death.

The names, also not mentioned in biblical texts, are more than likely an invention of Origen. After much changing of names, depending on which part of the globe you were from – in Europe they finally settle by the seventh century on the names Balthasar, Gaspar (or Caspar) and Melchior.

In conclusion, it is clear from the disparity between the images and the word, that the power of the image has triumphed in contemporary society, as it has done throughout the last two millennia of depictions of this story. Furthermore, in our contemporary secular society we are more likely to glean our information regarding this story from pictures in art galleries than from reading the Bible – or in my case play the part of one of the kings in the school play. No prizes for guessing which magus I played.

Leslie Primo, independent art historian