Botticelli, Rubens, Rembrandt, Tintoretto, da Vinci, El Greco (to name but a few): all have put paintbrush to canvas to give us their renditions of the nativity scene, or a part of the Biblical story of Christ’s birth. The sheer number of nativity paintings in existence – even just the ones hanging on the walls of the National Gallery – mean that we can barely scratch the surface in just one mere article. Here, we’ve chosen to highlight five nativity paintings with something different about them: a feature that makes them stand out in some way and makes them a bit more unusual.

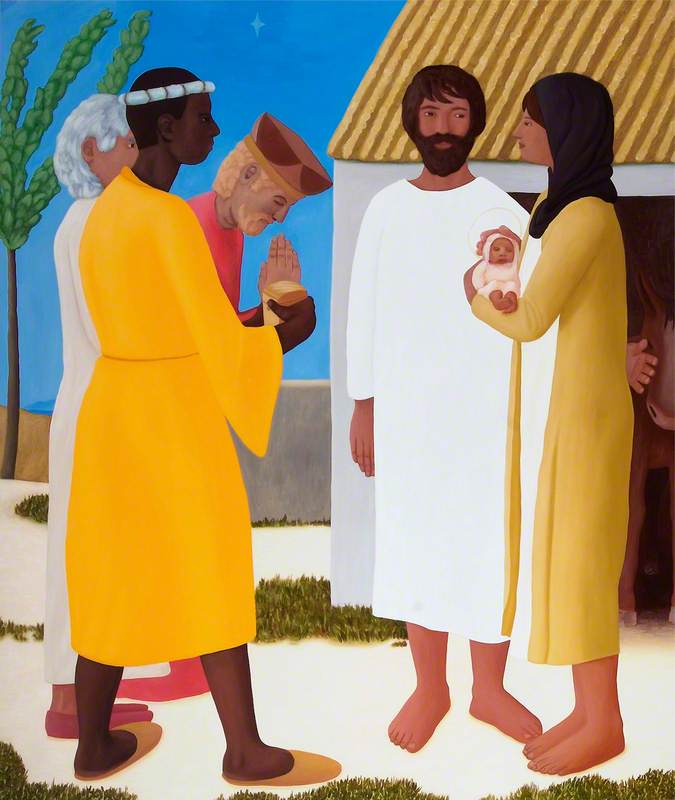

The one that sold for one guinea

A few years before he was busy painting pictures of Satan smiting Job with boils, or a monstrous creature as a representation of a bloodsucking flea, Blake produced a series of around 80 Biblical narrative paintings. These were all created using the same method – glue tempera on canvas – and paid for by Blake’s recently-acquired patron, Thomas Butts, at one guinea per painting.

Blake’s rendering of the kings visiting Jesus features a stylised star in the top corner, but otherwise feels a quiet and awed take on this part of the Christmas story, while still retaining a sense of Blake’s mysticism. The colours are muted, partly due to the glue tempera, which doesn’t hold up well to age and atmospheric changes. Nevertheless, a golden glow still surrounds the baby Jesus, eagerly reaching out his little hands to the offered gifts. This painting is not as extraordinarily brightly-hued or glossy as many of the most famous nativity scenes, but it still feels quietly reverent.

Sadly, Blake’s extraordinary piece The Nativity, in which the baby Jesus magically hovers in the centre of the barn (having apparently sprung miraculously from Mary’s womb), is not on Art UK – but we thoroughly recommend having a look anyway.

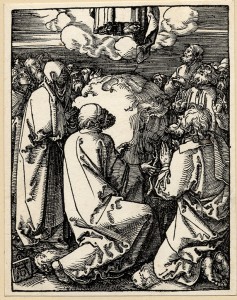

The one focused on Joseph

This is technically not a nativity scene, but a part of the Biblical story that took place prior to the arrival of baby Jesus.

Unusually, we are shown Joseph’s side of the story, as he is visited in a dream by an angel. In the Gospel of Matthew, Mary is pledged in marriage to Joseph when he discovers she is pregnant, and he considers divorce. To change his mind, God sends an angel in a dream to explain the divine conception and asking him to name the baby Jesus. The rest, as they say, is history.

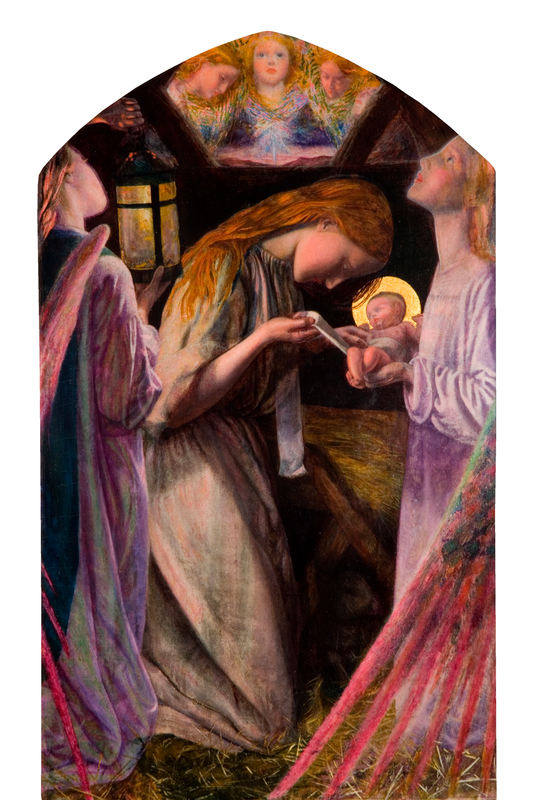

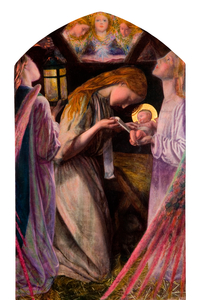

The one that’s all about Mary

Moving swiftly into the nineteenth century, Hughes’ nativity is notable for the very different, very young-looking Mary at its centre: usually, she is painted as a grown woman.

Compared to the other paintings in this list, The Nativity is also the least overtly Biblical (a reflection of being painted at a less God-fearing time), focusing instead on the innocence of Christ’s mother and the surrounding angels, who are painted to look very similar to Mary herself. The presence of the angels here seems more significant because of Mary’s adolescence: representing a celestial force watching over Mary and baby Jesus, her age perhaps suggesting she needs more guidance than in other depictions of this scene.

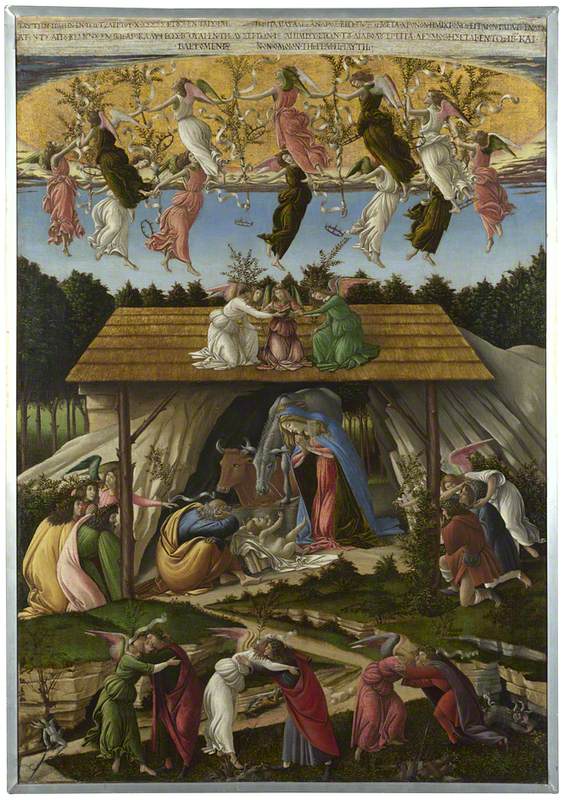

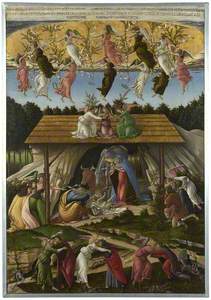

The one that depicted the second coming

This nativity is unusual for a number of reasons. Firstly, while we’re used to seeing Mary, Joseph and the baby Jesus as the main focal point of the nativity scene, here they are relegated somewhat to second place as your eye is drawn more immediately to the choir of angels, the opening of heaven and vivid struggles with men and devils.

Then, you realise that not many artists combined their depiction of the birth of Christ with a vision of the Second Coming as promised in the Book of Revelation. This Second Coming – Christ’s return to earth – would supposedly ‘herald the end of the world and the reconciliation of devout Christians with God’. This piece was painted a millennium and a half after the birth of Christ, when Europe was experiencing religious and political upheaval, leading Botticelli to believe he was living during the ‘Tribulation’, among dark prophesies about the end of the world.

So here we have the nativity scene – usually a still, peaceful moment – topped and tailed by devils fleeing to the underworld (the bottom of the painting) and text announcing the defeat of the Antichrist and the second coming of our Lord (the top, above the angels). And thus you have a painting which is a beautifully realised, but not at all traditional, rendering of the nativity scene.

The one set at night

The Nativity at Night

possibly about 1490

Geertgen tot Sint Jans (c.1460–c.1490)

This isn’t the only depiction of the nativity scene at night, but it was one of the earliest, and – according to the National Gallery – is one of the most engaging. The stark contrast between the dark of the surroundings and the light of the baby Jesus makes this painting feel particularly miraculous.

It’s easy to only focus on the foreground when you first look at this painting: the radiance of the baby Jesus, the quiet, awestruck face of Mary, and the reverence of the angels gathered around. Joseph is almost painted out of the family portrait, and is literally left in the dark. A second source of light comes from the background, where the shepherds kneel before a dazzling angel, telling them the news.

This nativity, perhaps more than any of the others on this list, really gives the sense of this singular moment of such quiet reverence yet immense importance. Everything has been changed irrevocably by the birth of Jesus, and for the people of this darkened world nothing will ever be the same again. Yet this particular moment of wonder is frozen in time, as Mary simply gazes on her son.

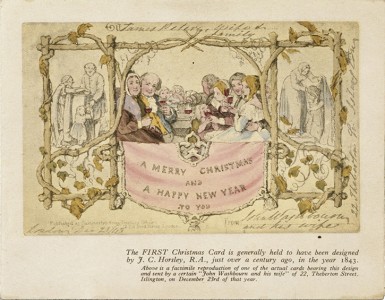

Merry Christmas and happy holidays from all at Art UK.

Molly Tresadern, Art UK Content Creator and Marketer