For many people across the UK, from a wide variety of backgrounds and faiths (or of no faith at all), December is a time of festivals and celebration.

From Hanukkah to Christmas, the winter solstice to the new year, the depths of winter are seen as the perfect time to inject a bit of happiness and cheer into the year. This might explain why so many December festivals involve lights, candles, fire and belt-bursting quantities of food and drink – when the days are at their darkest, we all need something to chase away the shadows and bring some comfort to the soul.

This urge has been with us for thousands of years, and over time midwinter traditions have passed from culture to culture and festival to festival, helping to explain the plethora of celebrations we have at this time of year. Christmas alone has roots that go back 5,000 years, from our Neolithic ancestors feasting during the solstice through Roman Saturnalia, pagan Yule, medieval Christmas and the Victorian traditions which have so strongly shaped our modern celebrations.

A Winter Scene with Skaters near a Castle

about 1608-9

Hendrick Avercamp (1585–1634)

So tuck yourself a little tighter under that blanket, make sure some seasonal snacks are within reach and come on a little tour of a few festive artworks.

Our first December festival this year is the eight-day Jewish celebration of Hanukkah, which wanders around December (and even into November, as it did in 2021) depending on the Jewish lunar calendar. Hanukkah celebrates the liberation of the Temple in Jerusalem by Judah Maccabee and the subsequent 'miracle of the oil', when just one day's worth of ceremonial oil burned for eight whole days.

Despite its minimal religious significance, Hanukkah is keenly looked forward to by Jewish children (and adults), as gift-giving, games and copious quantities of fried potato latkes (not dissimilar to hash browns) and doughnuts all make an appearance.

8th December marks the celebration of the Buddhist holiday known as Bodhi Day (in countries such as China, Korea and Vietnam) or Rōhatsu (in Japan). While the precise traditions may vary between different countries and sects, they all commemorate the day that the Buddha experienced enlightenment while sitting under a sacred fig tree and meditating.

Those celebrating Bodhi Day might themselves meditate, study or perform charitable acts. As with many winter festivals, people light candles or hang coloured lights, and there may also be cookies (because all winter festivals are better with cookies).

OK, so this might not be the most obviously festive sculpture, but bear with us.

Saturn Devouring His Son

1750–1880

unknown artist

It represents the Roman god Saturn, from whom we get the name for the planet and the sixth day of the week. In mythology, he has been conflated with the Greek Titan Cronus, father of Zeus.

Cronus/Saturn's main claim to infamy was his nasty habit of consuming his children upon their birth to avoid them overthrowing him. However, Saturn also gave his name to the carnivalesque Roman festival of Saturnalia, traditionally celebrated on or around 17th December, hence his inclusion here.

Moving on through December we come to the northern hemisphere's winter solstice, which falls on either 20th, 21st or 22nd December. Numerous festivals are associated with the winter solstice around the world, from Yaldā Night in Iran to the Chinese Dongzhi Festival. In Europe there are several pagan and Druidic traditions of varying antiquity tied to the winter solstice, and prehistoric sites such as Newgrange in Ireland and Stonehenge in England (illustrated here) were built to align with solstice sunrises and sunsets.

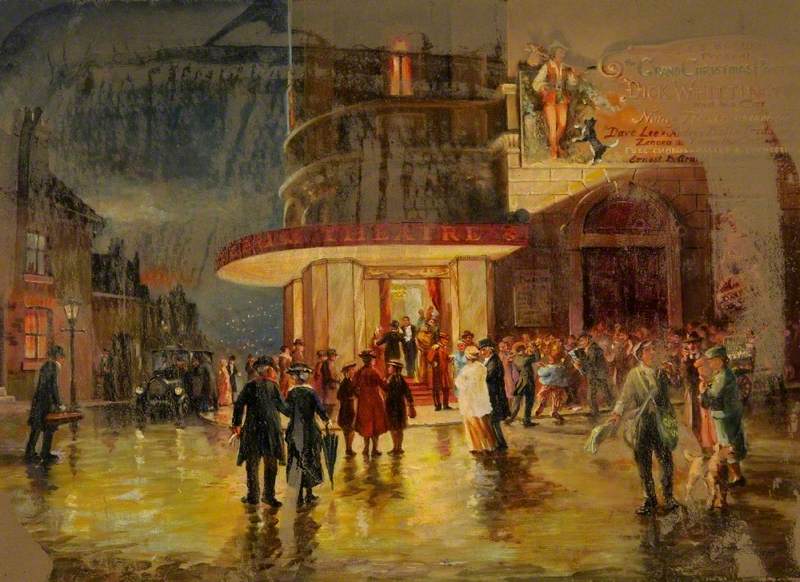

For many, a visit to a play or a panto is a key part of the festive season. Jennings' painting captures the golden glow of a theatre at night, and the childhood excitement of seeing Dick Whittington on the stage.

Christmas Eve, 1932 (First Night of the Pantomime at the Lyceum Theatre, Sheffield)

2003–2004

Roberta Louise Jennings (1919–2018)

The Covid lockdowns have been incredibly tough for theatres around the UK (and further afield). Hopefully, Christmas pantos this year will be able to help them get back on their feet.

Father Christmas. Saint Nicholas. Sinterklaas. Santa Claus. Call him what you will – some sort of gift-giving, coal-carrying, reindeer-riding figure is a staple of European and American Christmases.

Today, we're used to thinking of Father Christmas as being a jolly old man with a long white beard, wearing red and bearing gifts for children. This Father Christmas, dressed in white, wearing a wreath of holly and sitting before a sumptuous spread of food, harks back to his more ancient (and grown-up) roots in feasting and merry-making.

Although not perhaps a typical Christmas scene, there is definitely something suggestive of an elf's hat about the red triangular shape in the centre of this work.

Rae was able to spend time living and working in Mexico and Spain, where this is set. Ronda is in the far south of Spain, just 30 miles from the coast. While it might not represent a typical UK Christmas, it would definitely be nice to be able to spend December somewhere warm and sunny this year.

Most of us can probably relate to this Boxing Day picture.

Everyone's knackered, the house is a wreck and all we really want to do is sit in a heap on the floor. It's not clear where the adults are in this scene – presumably desperately sleeping in for as long as they can. Unfortunately, the trumpet being wielded by the girl to the right suggests that any lie-in may be about to be cruelly cut short...

In Scotland, midnight on 31st December marks the passage from the old year to the new. Hogmanay celebrations take two whole days to complete, not finishing until 2nd January, when the rest of the UK is already back at work.

Fire (or fireworks), gift-giving and, of course, whisky all make prominent appearances during the festival. In Stonehaven, near Aberdeen, locals process through the town swinging two-foot fiery balls around their heads while the 1996 Hogmanay party in Edinburgh attracted almost 400,000 people, nearly doubling the city's population at a stroke. Not a bad way to say: Happy New Year!

Ben Reiss, Collections Content and Liaison Officer