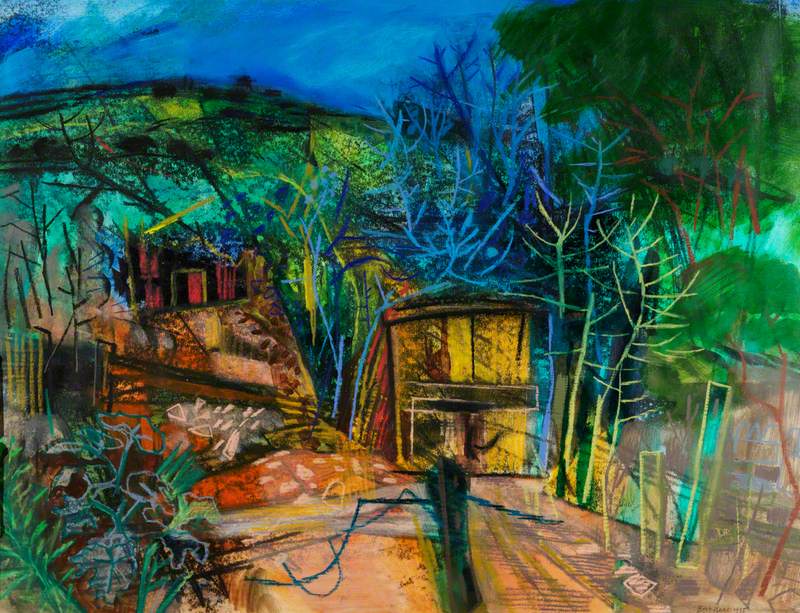

When I moved to Wales, I missed home. My homesickness was at its deepest during the Christmas season. In Trinidad and Tobago, we have preserved a Christmastime house-to-house Spanish-speaking music tradition called parang. The parangderos entertain with singing and dancing and are welcomed by the hosting homes with an abundance of Christmastime food and drink. On neighbouring lands, we see Junkanoo, Masquerade or Wanaragua. These colourful masquerades with music and dancing speak of celebration, reimagination, resistance, memory and paths that have crossed.

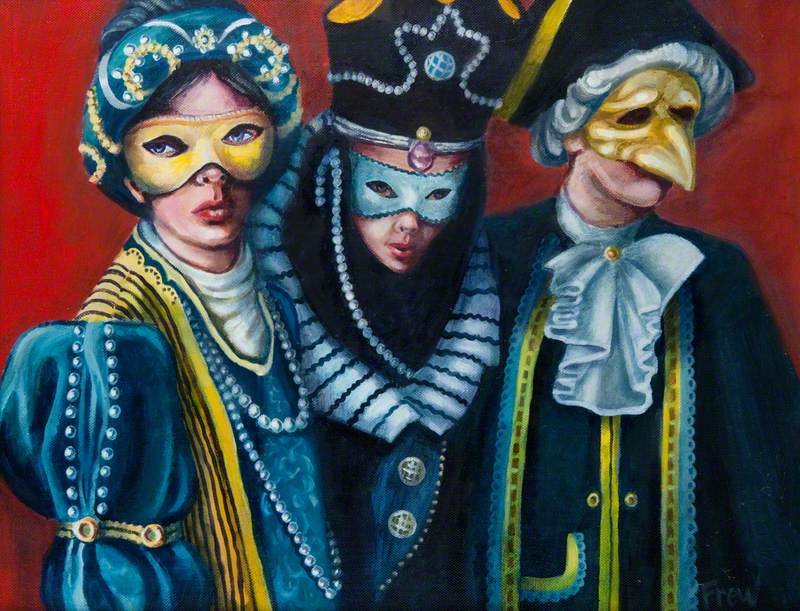

Trinbagonian Carnival designer Peter Minshall said that to carnival is universal – that every society has the need to celebrate life. I'd add that to masquerade – as a performative, often ritually significant action of masking and adorning, with music and dancing within a communal setting – is also linked to this need to celebrate life.

In Trinidad and Tobago, our masquerade tradition of Carnival takes place within the Lenten calendar – 40 days before Easter. Our Carnival is rooted in emancipation and some of our characters share visual aesthetic traits with Christmastime Junkanoo characters. In my early years in Wales, I was not aware of the aesthetic links between Wales' y Fari Lwyd (or the Mari Lwyd, 'The Grey Mare') and Jamaica's Junkanoo 'Horse Head'.

Y Fari Lwyd is a Welsh Christmastime masquerade tradition that involves a main character clothed in a sheet decorated with ribbons, propping up a horse's skull. The entourage sometimes includes characters such as Punch and Judy, the Sergeant and the Merrymen. My attraction to the Mari Lwyd was in the recognition of a folk form that spoke to a shared language of community memory, transformation and joy.

View this post on Instagram

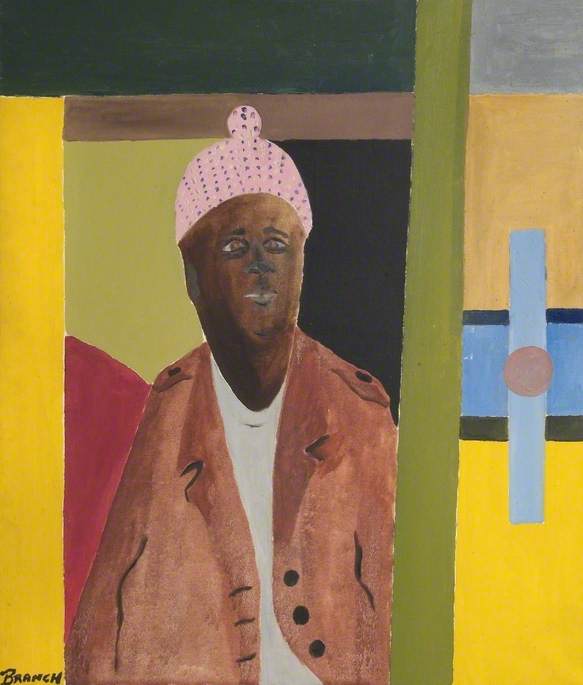

During my initial years in Wales, there was a Caribbean-inspired Carnival in the city of Cardiff. The indigenous Butetown Carnival was, at the time, on hiatus. While the Cardiff Carnival was wonderful, I wondered about Welsh traditions of masking that were rooted in the history and landscape. Rugby fans on match days seemed to offer a glimpse of a mass celebratory transformative spirit with which I was trying to connect. Encountering the Mari Lwyd offered another perspective.

While at the pub with his friends almost 20 years ago on a cold damp winter's evening, my then-husband shared a video of an encounter he was having with y Fari Lwyd. I recall the excitement and warmth I felt, witnessing, for the first time, the communal signing and the masquerade dress.

View this post on Instagram

There is usually improvised rhyme and verses (pwnco) sung in Welsh, at the threshold of the pub or house where the crew ask permission to enter. Initially, they are refused entry and then, as the verses continue, Mari Lwyd and 'her' crew are allowed in. Once inside there is much dancing and raucousness, while masquerade guests are served food and drink. Y Fari Lwyd masquerade performance is linked to blessing the home for a bountiful year ahead.

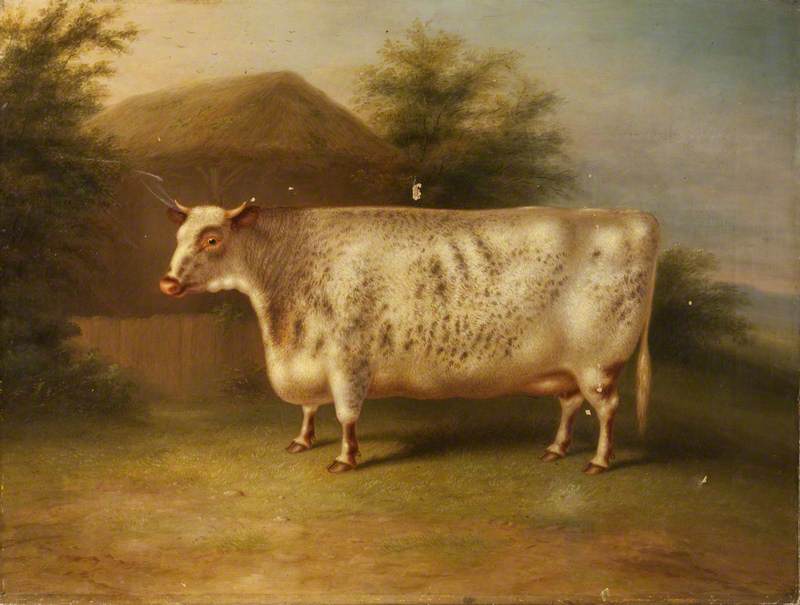

The character of the horse is common in hobby horse masquerades. Becoming animal, with the wearing of animal parts, is a familiar shamanic performance activity related to invoking the energetic qualities of the animal – strength, protection, agility and so on. Horses tend to represent courage, youthfulness and freedom.

In Sierra Leone, we see the secular Odelay masquerades that have been influenced by sacred hunter societies. Visual manifestations of this Odelay masquerade involve the wearing of a horse's skull (or the head of any animal that is hunted). Sometimes the head might be a carved version rather than the real skull. The masquerader will be draped in ornate fabric or robes decorated with shells and palm leaves, and carry a broom made from the tail of a horse or cow.

In Jamaica, different parishes are known for different characters. The main Jonkannu characters include Cowhead (who brandishes the horns of a cow), Pitchy Patchy (a dancing character covered in colourful strips of fabric), Horse Head, a Devil character, Belly Woman (with exaggerated or pregnant belly features) and the King and Queen, Policeman, Jack-in-the-Green, Wild Indian and Bride and Groom.

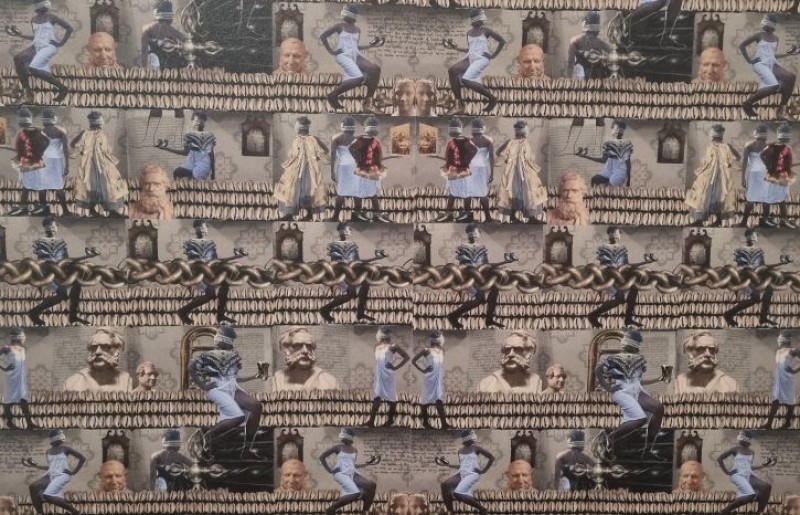

The Jamaican Jonkannu was likely brought to the island by the followers of Akan chief 'John Canoe', who became prisoners of war and were enslaved on the island. Jonkannu-ing was an act of remembrance and resistance. John Canoe probably carried the Akan name Kenu, which was corrupted by the British to John Canoe. John Canoe was a powerful Gold Coast merchant who defended his land from European invaders for 20 years.

According to eighteenth-century Jamaican plantation owner Edward Long, the Jonkannu masquerade includes motifs like that of the Akan: the Ashanti swordsman resembles the Cowhead costume and the Ashanti commander the Pitchy Patchy.

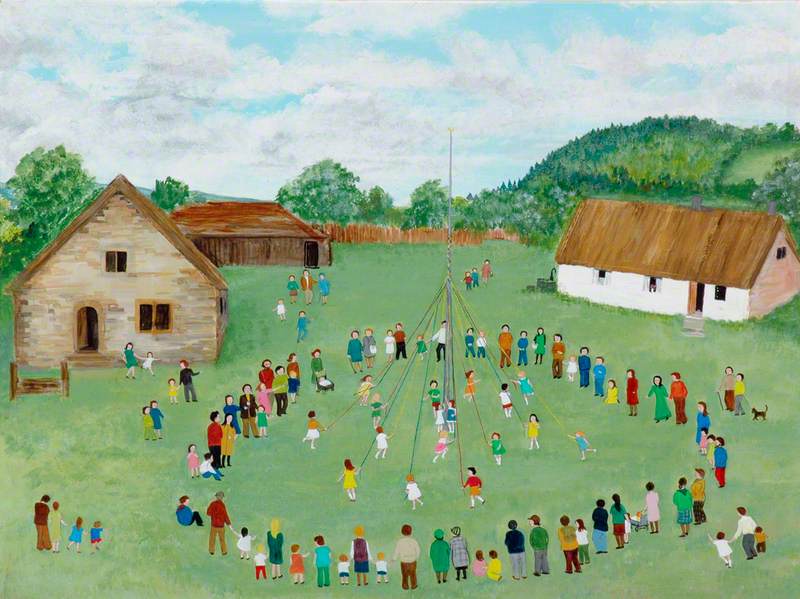

Although the Jamaican Horse Head is remarkably similar to y Fari Lwyd, this character has clear links to West Africa. We know that the British colonised Jamaica from 1655 to 1962. We are also aware that amid the violent inhumane regime, indentured working-class Britons served as bookkeepers and overseers. There is still evidence of British folk traditions such as mumming (or mummers') plays and maypole dances in Jamaica. Could Mari Lwyd have danced in Jamaica too?

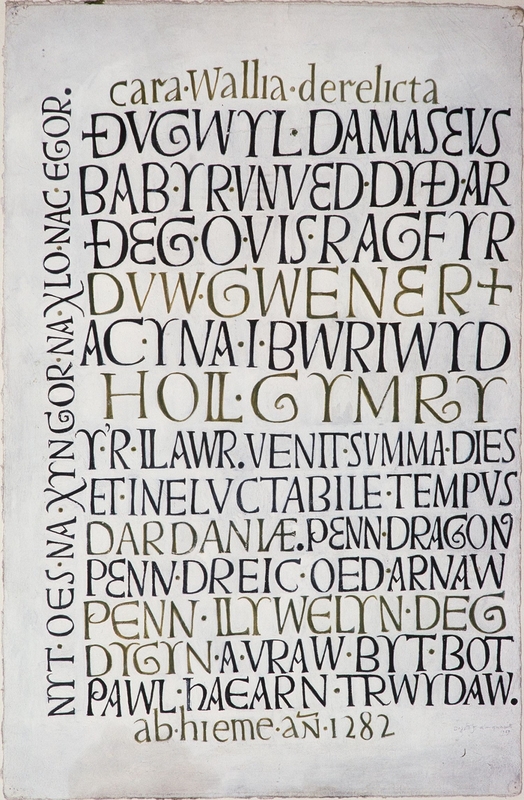

In Wales, y Fari Lwyd speaks to notions of resistance, Welsh identity and joy – through language and folk preservation. The horse's skull is usually buried and 'reborn' the following year. In recent years, there have been more enactments of y Fari Lwyd. I see the enactments of this folk performance of masking, dancing and singing as ways of remembering rites.

I see masking as a portal – a way of becoming and allowing access to an 'other'. Mari Lwyd's original role of blessing the home may be less evident in contemporary portrayals. However, the performative prancing gestures, the playful pwnco and the community joy that encompass the ritual potentially still invoke the sacred sentiments of the past.

Through y Fari Lwyd my hiraeth was temporarily soothed by a warm familiarity of masking, folk and community joy. Much like the story of Carnival in Trinidad, Junkanno and Mari Lwyd masquerades tell of encounters, cultural retentions and honouring traditions.

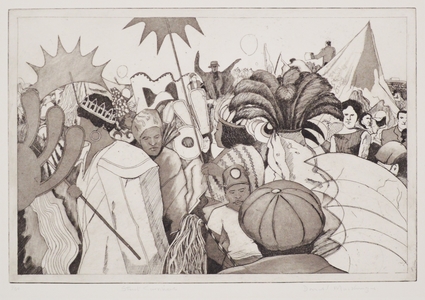

A Little Bit Tipsy, Christmas Eve, 1996 (The Old Hoss)

1996

William A. G. Ward (b.1926)

Christmastime traditions, masquerades and carnivals have always fascinated me. My growing up experiences in Trinidad and exposure to Carnival informed an appreciation for the capacities of folk festivals, carnivals and masquerades, to nurture and build community identity through public celebratory enactments that utilise masking, music and movement.

The significance of y Fari Lwyd performance aesthetics, for me, lies within the ways in which these folk traditions of transformation reclaim collective joy, linking people and culture – affirming a need to masquerade as a way of celebrating life in an increasingly polarised world.

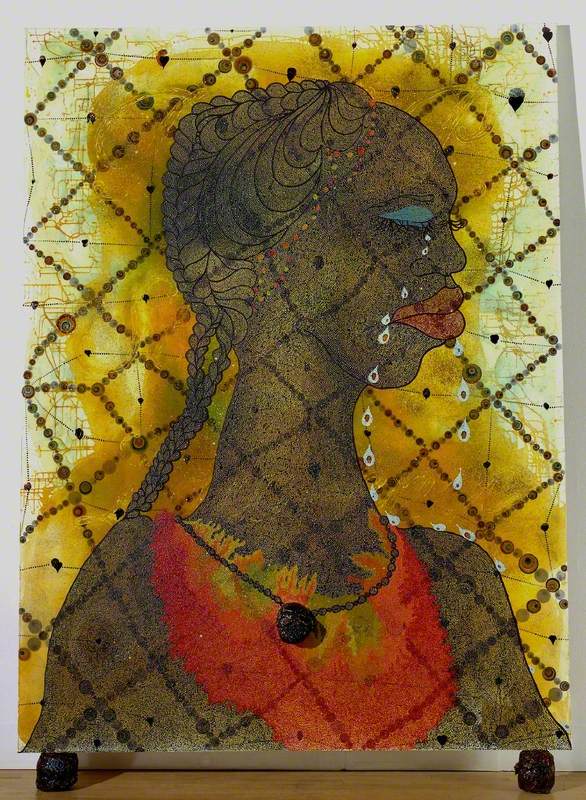

Adéọlá Dewis, artist and researcher

HorseHead was commissioned by the National Library of Wales in 2023, as part of a wider project to decolonise the art collection, in support of the Anti-racist Wales Action Plan

Special thanks to interviewees Paul Anaman, Honor Ford-Smith, Tutie Haffner, Rhiannon Ifans, Marie Kellier, Peter Minshall and Alexander Tetteh Quaynor

This content was supported by Welsh Government funding

Further reading

John Nunley and Judith Bettelheim, Caribbean Festival Arts: Each and Every Bit of Difference, University of Washington Press, 1988

Rhiannon Ifans, Stars and Ribbons: Winter Wassailing in Wales, University of Wales Press, 2022