The recent success of the Netflix series Bridgerton has thrown the norms of the period drama up in the air with its energetic sex scenes, colour-blind casting and riotously colourful costumes.

Set in London in 1813, the show brings the Regency period, with all its excesses and intrigues, vibrantly to life. As the refined Bridgerton family and nouveaux riches Featheringtons negotiate the all-important 'Season', when eligible husbands must be found for their daughters, the viewer is treated to a feast of fashion.

View this post on Instagram

In anticipation of the impact of the show, fashion designers across the world have been inspired to rework the Regency look ahead of February's London Fashion Week, giving rise to trends such as 'Regencycore'.

Designers such as Erdem, Loewe and Rodarte have incorporated Empire-line dresses, short puffed sleeves, pearl headbands and billowing clouds of tulle in their latest collections, and according to the search platform Lyst, online searches for corsets have risen by over 100%.

The Bridgerton costume designer Ellen Mirojnick used paintings from the Regency period for inspiration but admits to pursuing her own vision, using a rainbow of colours and lavish embellishment to signify class, status and character. But when we look at paintings, how true a picture do we get of the fashions of the period anyway?

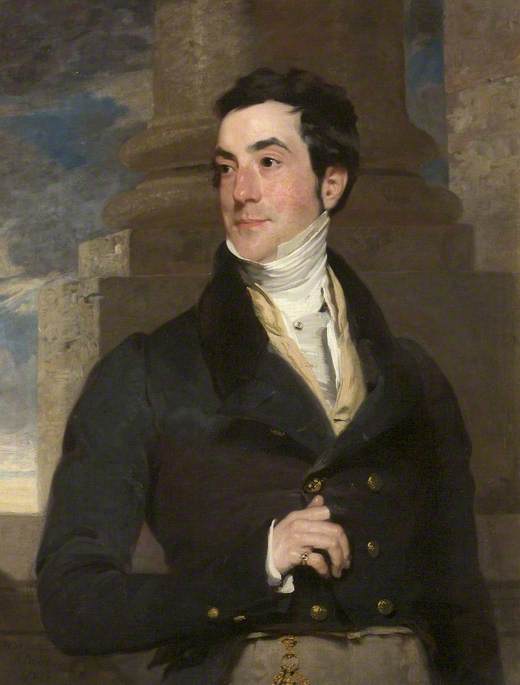

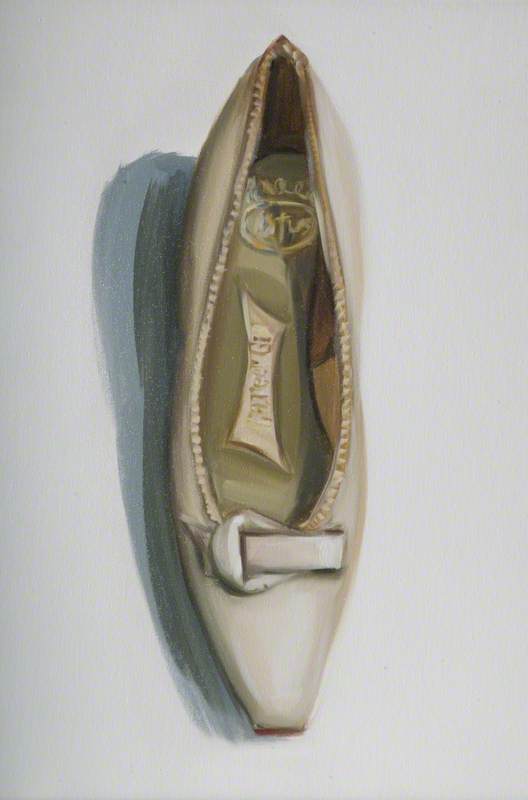

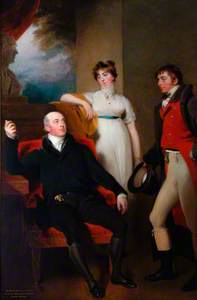

Image credit: Museum of Freemasonry

HRH George (1762–1830), Prince of Wales, KG

Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830) (studio of)

Museum of FreemasonryThe 'Regency' in British history describes the period 1811–1820 when the flamboyant, fashion-loving Prince of Wales (later George IV) acted as regent during his father, George III's, episodes of mental illness.

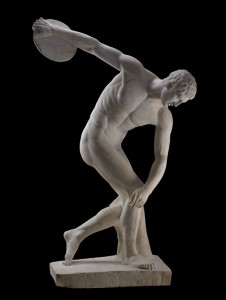

However, the Regency 'era' is often taken to mean the years 1790–1830 in terms of style and fashion, as it marks a tumultuous time in history coloured by the success of the revolutions in France and America, and the Industrial Revolution, which brought the mechanisation of industry and the advent of mass consumerism to Britain. From 1793 to 1815 England was almost constantly at war with France, battling Napoleon's imperial ambitions whilst absorbing much of France's influence in the decorative arts and fashion. Neoclassicism, the prevailing style in France, combined with a new post-revolutionary social mobility to usher in an age of looser, simpler dress for women, referencing the ancient world.

Pinched waists and hooped skirts gave way to a straight silhouette typically in white gauzy fabric such as muslin, characterised by a low, scooped neckline and high 'Empire-line' waist wrapped round with a coloured sash. Although initially it was worn with undergarments such as the chemise, the more daring women scandalised society with almost transparent dresses, leading some to call this the 'age of undress'.

Image credit: The Henry Barber Trust, The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham

Madame Juliette Récamier (1777–1849) modelled c.1802; this version early 19th C or later

Joseph Chinard (1756–1813)

The Barber Institute of Fine ArtsMadame Juliette Récamier, the socialite and legendary beauty whose Parisian salon attracted a literary and political entourage, was an icon of neoclassicism who embodied the sensuousness of the diaphanous dress. Here she is sculpted almost as a Greek goddess.

Image credit: Lady Lever Art Gallery

Lady Hamilton (1761–1815), as a Bacchante

Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun (1755–1842)

Lady Lever Art GalleryEmma, Lady Hamilton is purported to have worn an alluring semi-transparent dress on first meeting Lord Nelson. In this painting of her as a bacchante, she wears a layered robe, showing a patterned underdress, and dances against a backdrop of the eruption of Vesuvius. The subsequent excavations at Pompeii, which had begun in 1748, were another source of fascination with the ancient world.

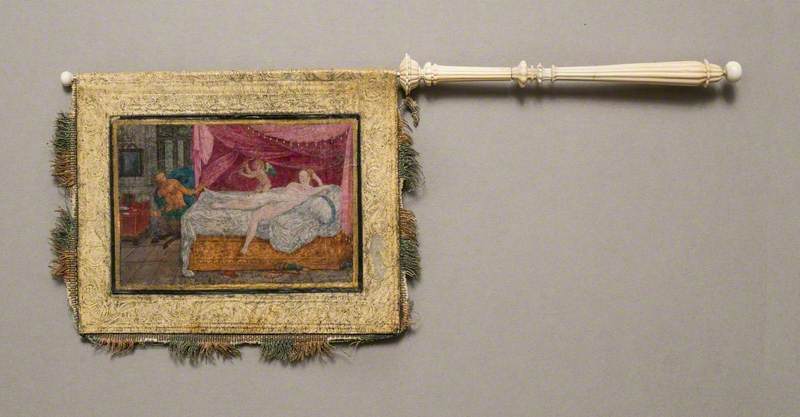

Image credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Paulina (1784–1823), First Wife of Sir Codrington Edmund Carrington c.1806

Thomas Lawrence (1769–1830)

Paintings CollectionSociety portraitists of the time, such as Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le Brun and Thomas Lawrence, who excelled at painting fabrics, often favoured the neoclassical look over high fashion as it rendered the painting more timeless and engendered a certain nobility in the sitter. Finding depictions of up-to-the-minute fashions in bright colours can therefore prove a challenge, although, in the case of Paulina Carrington, Lawrence was bold enough to capture the fashion of visible nipples. Coral necklaces, deemed to have mystical and medicinal properties, including warding off infertility, were often given as gifts to young girls. Along with pearls, they were popular at this time as they set off a low-cut neckline to effect.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0)

The Graces in a High Wind

1810, engraving by James Gillray (1756–1815)

The Empire-line dresses, with their gossamer fabrics which outlined the body in the manner of classical statuary, provided rich fodder for satirists who mercilessly lampooned the new style for its impropriety and impracticality. James Gillray here references the Three Graces while ridiculing the dresses' tendency to provide a very unforgiving outline of the body in bad weather.

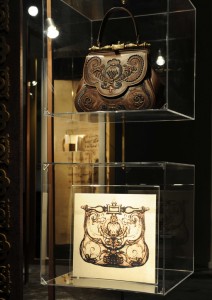

With advancements in spinning, weaving and fabric printing, as well as improved transportation, fashion started to move at a faster pace and dressmakers started to distribute fashion plates to their customers to keep them abreast of the latest trends. Many of these, such as those found in Ackermann's Repository of Arts, a monthly periodical published from 1809 to 1828, highlight the fact that brightly coloured ostentatious garments were indeed popular, though these are rarely represented in portraits. In the case of Lady Burdett's morning walking dress, a strikingly similar description can be found in an Ackermann's of 1813: 'A round robe of Cambric muslin, with long full sleeves, and simple short collar, confined in the center [sic] of the throat with a stud or broach, the same fastening at the wrist.'

As well-to-do women's lives revolved largely around social gatherings, several changes of dresses were needed during the day. The Countess of Blessington is shown in a satin evening dress with a low square neck and bodice in tulle adorned with a corsage of flowers. The neoclassical style remained popular into the 1820s but after 1810 women started to wear corsets again, which pushed the breasts upwards and, in the case of the 'divorce corset' possibly worn here, thrust them apart by means of a piece of padded steel.

Image credit: Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art Gallery

The Honourable Miss Caroline Fox (1767–1845) 1810

James Northcote (1746–1831)

Royal Albert Memorial Museum & Art GalleryNaturally, the more flesh-baring styles were of limited appeal to the older woman but the Empire-line dress could be worn with greater modesty with an overdress or attachment to the bodice finishing in a high ruffled neck. Diarist and columnist Miss Caroline Fox was 43 years old when this portrait was painted. She demonstrates the fondness for shawls, in particular red paisley-patterned ones from India, which were much needed to provide warmth over the flimsy dresses. Fashion plates show that short spencer coats, long coats such as redingotes (based on the riding coat) and high-waisted pelisses offered an alternative, but these are less often seen in portraits, even in an outdoor setting. Clearly there would be conflict with the classical ideal.

The ruffled neck acquired more extreme forms as a revivalist attitude took hold, born of a new patriotism following the defeat of Napoleon at Waterloo in 1815. Fashion looked back to the Elizabethan era for its inspiration, and red velvets, slashed and puffed sleeves trimmed with pearls and ermine capes lent a theatrical air to social events. At the same time, a combination of style-setting gentlemen returning from the Grand Tour, increasing trade with the empire, and the Prince of Wales' construction of the flamboyant Eastern-inspired Royal Pavilion in Brighton sparked a revival in the wearing of turbans.

Image credit: National Trust Images

Lady Harriet Cavendish (1785–1862), Countess Granville c.1809/1810

Thomas Barber (1771–1843)

National Trust, Hardwick HallAnother reason for the adoption of 'Oriental' dress may have been the visit of Mirza Abu'l Hassan Khan, the emir of the Shah of Persia who was sent to the court of George III in 1809 to help negotiate a treaty of alliance between Great Britain and Persia (now Iran). Many parties were held in his honour and he became a figure of fascination for London society.

Image credit: Compton Verney

Mirza Abu'l Hassan Khan (b.1776), Ambassador for the Shah of Persia 1809–1810

William Beechey (1753–1839)

Compton VerneyBy contrast, the men of the 'ton' – the term derived from the French 'le bon ton', meaning good manners and used to refer to high society – took their lead from Beau Brummell, a close friend and powerful influence over the Prince of Wales in matters of grooming and dress. Developing his personal look from military tailoring, he recommended a 'less is more' approach, advocating a sharply tailored wardrobe consisting of a cutaway coat, often of dark blue, a straight-cut waistcoat and close-fitting full-length buff trousers tucked into riding boots. A scrupulously clean linen shirt was worn underneath with the neck finished by a high stock and cravat tied with a flourish. The high stand of both the cravat and coat collar lent the wearer an air of superiority.

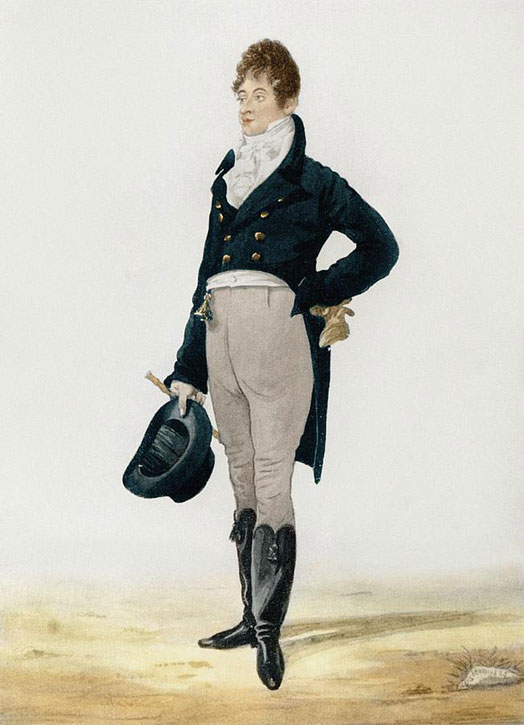

Image credit: Bonhams, public domain

George 'Beau' Brummell (1778–1840)

1805, watercolour by Robert Dighton (1752–1814)

Brummell's ideal was to 'clothe the body that its fineness be revealed' and he held equally strong views about the importance of hygiene and personal grooming, spending many hours at his toilette. Although France had led the way in fashion in the late-1700s, Brummell's style was so influential that it not only turned English city dwellers into a nation of dandies but migrated across the Channel where it was readily adopted by the French. At a time when social mobility had increased in the wake of the French Revolution, Brummell was evidence that style and personality, as much as wealth and rank, could buy you a place in society. He is still remembered today as the perfect embodiment of the 'dandy'.

In both the portraits above, a cluster of personal fobs or seals is visible at the right-hand side of the waist. Seals were still used to sign documents and it was fashionable to display them, while keeping a pocket watch out of view. This decorative accessory was succeeded by the watch chain towards the end of the nineteenth century. Following the introduction of a duty on hair powder in 1795, to help finance the wars against France, the wearing of wigs declined and men wore their own hair, styled à la Brutus or à la Titus, emulating the heads of Roman statues. Women also cut their hair short or piled it up with tight curls along classical lines.

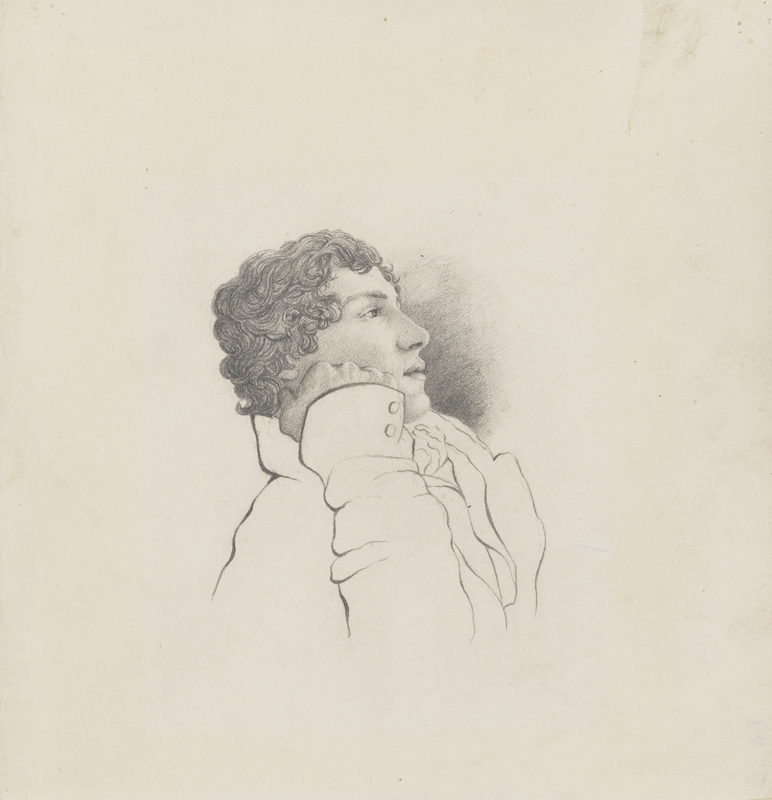

Although society portraits tend only to give a window on the world, and hence the fashions, of the elite, at this time of growing enlightenment, portraiture started to incorporate scientists, inventors and artists for whom dress was less formal. This was also the age of the Romantic poets who espoused the celebration of the natural world and railed against the rapid industrialisation and consumerism of the cities.

This portrait of the poet John Clare embodies his artistic temperament with its loose-cut brown jacket, soft-collared shirt and bold-patterned cravat, suggesting a dreamier character more suited to roaming mountains and composing lines of great beauty than attending a society ball.

We understand when we watch a costume drama that both the storyline and the wardrobe are works of fiction, designed to evoke a period or character rather than provide accurate historical representation. It is not so different with portraiture. As fashion historian Aileen Ribeiro states: 'When we contemplate portraits of famous figures of the past and present, their images are largely constructed – indeed created – by the clothing they wear.'

Lucy Ellis, freelance writer

Further reading

Daniel James Cole, 'Hierarchy and Seduction in Regency Fashion', Jane Austen Society of America, Vol. 33, No.1, Winter, 2012

Aileen Ribeiro, The Gallery of Fashion, National Portrait Gallery, 2000

The Royal Academy of Arts, Citizens and Kings, Portraits in the Age of Revolution 1760–1830, Royal Academy, 2006