'Life is short. Buy the bag', reads a poster I saw recently. But whether you know a Birkin from a Baguette, how is it that handbags have gone from the functional to the desperately desirable? The average waiting time for an Hermès Birkin bag is thought to be about six years, if you can get on the waiting list.

As the upcoming exhibition 'Bags: Inside Out' at the Victoria and Albert Museum (postponed because of the current lockdown) reveals, the handbag's evolution over the last 500 years shows it to be far more than a simple accessory.

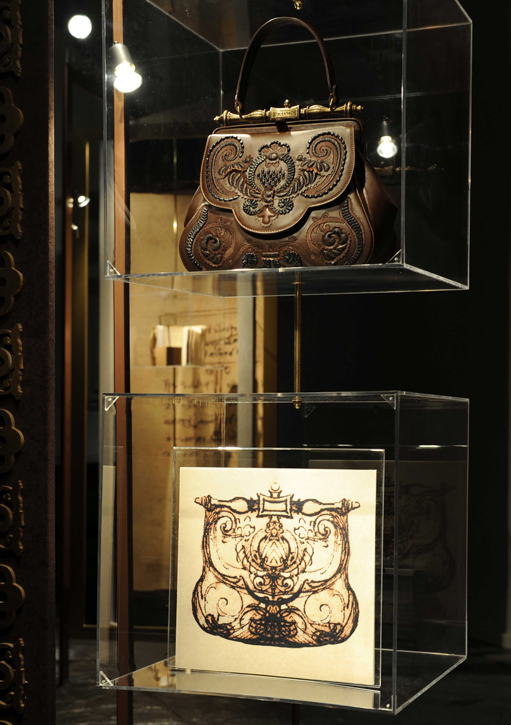

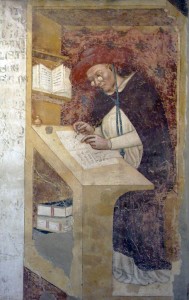

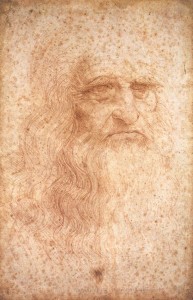

In Renaissance Italy when the first courier services began, mounted messengers used sturdy bags constructed from tooled leather to transport papers, cash and jewels between banks such as those owned by the Medici in Florence. Leonardo da Vinci, always ahead of his time, designed an elaborately decorated leather bag around 1497, about the time he was painting The Last Supper. The sketch, discovered by the Da Vinci scholar Carlo Pedretti in 1978, was brought to life as a beautiful bag in 2012 by the Italian fashion label Gherardini.

Sketch 'La Pretiosa' (below) next to the Pretiosa bag (above) based on the design

c.1400s, sketch by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519), 2012, handbag design by Gherardini

Leonardo's bag was not designed for a woman – money was generally carried by men in a pouch fashioned from cloth or hide and attached to a waist belt. Women wore purses as a fashion item or receptacle for small items, as pockets were not incorporated into dresses until the seventeenth century.

Richly embroidered purses were traditionally offered as a betrothal gift from groom to bride, often featuring poems and stories in their decoration. They hung on drawstrings from a woman's girdle along with items such as a rosary or pomander, a practice that prefigured the chatelaine, a waist belt which carried items in daily use, such as needlework scissors.

Marigolds (The Bower Maiden, Fleur-de-Marie)

1874

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882)

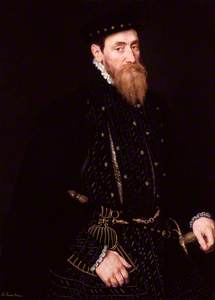

Men of high social status were able to demonstrate their wealth with a luxurious purse such as the one worn here by Sir Thomas Gresham, the founder of the Royal Exchange and financial agent to the Crown in the Elizabethan period. The velvet and gold purse is a signifier of his affluence and, as fashion historian Aileen Ribeiro notes, 'draws attention to his career as an astute man of business.'

By contrast, large bags and satchels worn across the body were used only by peasants and those who did not enjoy the privilege of having servants to carry larger items for them.

Flat-based gaming bags were common to both men and women but just as a gold-embroidered purse signified wealth and comfort and a robust satchel a life of toil, so the empty purse spoke of careless expenditure and the dangerous effects of the gaming table.

By the seventeenth century, women benefitted from pockets attached to a band tied over their petticoats and accessed through a vertical slit in their skirts. However it became common in the eighteenth century for ladies of leisure to carry their needlework around with them in a bag.

Initially, these were large, but as the fashion for knotting silk thread into lace took hold, workbags shrank in size. Arthur Devis' unknown lady is depicted knotting, as we can see from the shuttle held in her hand. This was considered a fashionable pastime for a woman of the upper-middle classes and, along with the house in the background, is a signifier of her status.

It was acceptable to practise knotting in public and to take your bag with you when visiting family and friends. Knotting bags were frequently made of silk and exquisitely embroidered but were not intended to coordinate with one's apparel.

George Thompson, his Wife and (?) his Sister-in-Law

c.1766–8

John Hamilton Mortimer (1740–1779)

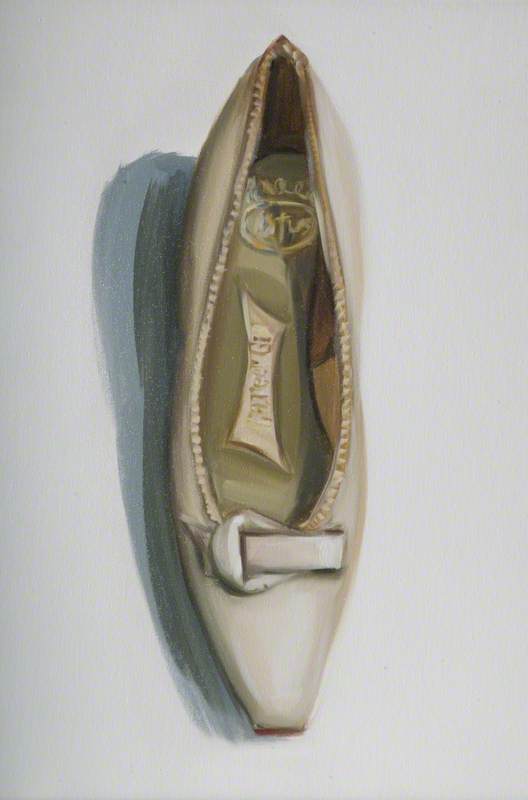

As the full-skirted dresses of the mid-eighteenth century gave way to the slim, columnar neo-classical fashions of the 1790s, pockets were replaced by a drawstring bag hung from the wrist known as a reticule, though often satirically referred to as a 'ridicule'. Once women had adjusted to using them, many called them 'indispensables'.

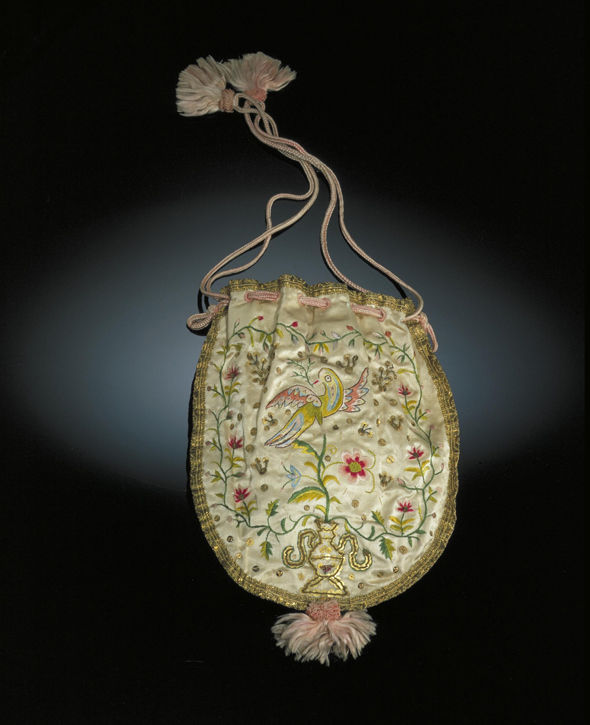

Bag

c.1790–1800, silk bag, embroidered with silk thread, with string tassel and straps by unknown maker

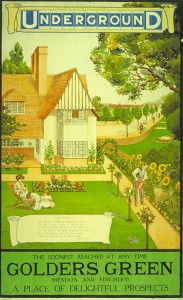

The nineteenth century heralded the age of steam and offered opportunities for travel across land and sea for all classes. Luggage, designed in matching sets for the well-to-do, might be carried by a porter but bags were needed to keep tickets, papers and money on the person and so the handbag as we know it was born. Victorian leather handbags often mimicked luggage or saddlery, fastening with buckles and clasps.

Bag

1889, leather, crocodile (alligator) and kidskin bag, with chrome fittings by unknown maker

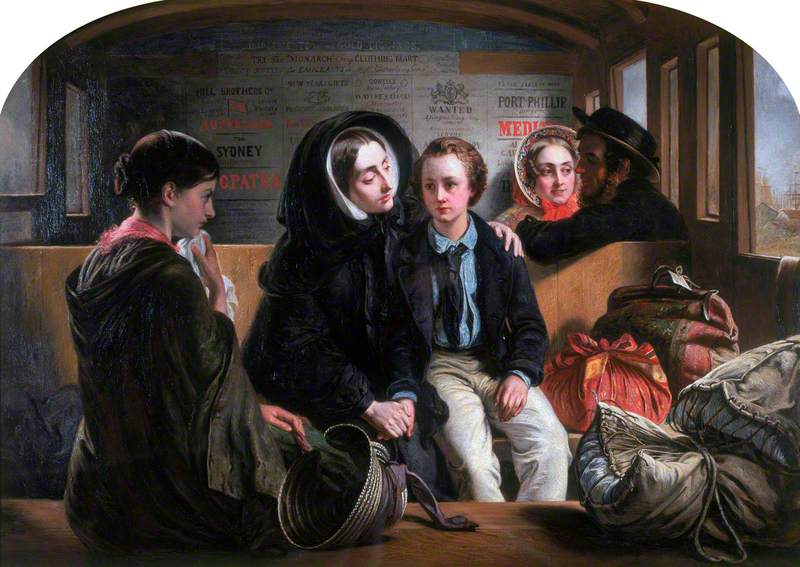

The more capacious Gladstone portmanteau bag, seen at the front of this painting, was ideal for travel and also proved enduringly popular with doctors.

Louis Vuitton created 'steamer bags' which fitted inside their trunks, while less wealthy travellers made do with carpet bags. Abraham Solomon made several copies of this popular painting, experimenting with different colours for the carpet bag in the corner.

Handbags entered their most innovative period in the twentieth century. As women enjoyed much greater independence, their bags had to carry all their necessities for the day – money, visiting cards, notebook and, increasingly, cosmetics, whose popularity had grown with the advent of motion pictures. Emile-Maurice Hermès, grandson of the founder of the saddlery company, was prompted by his wife's insistence to introduce the company's first handbag in 1922.

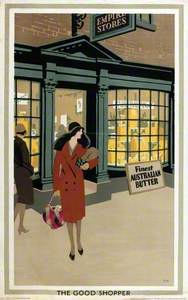

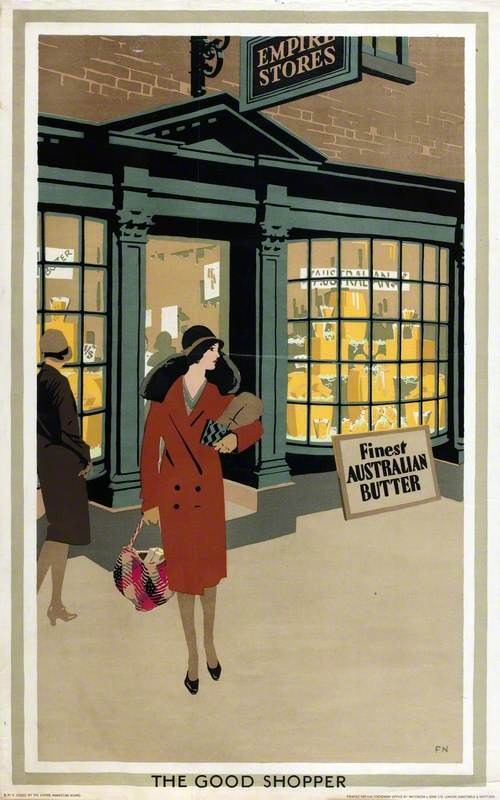

While the reticule – now known more commonly as a Dorothy bag – made a return in the 1920s adorned with fringing and beading as the perfect complement to flapper-style dresses and dance crazes such as the Charleston, the clutch bag arrived on the scene as the perfect canvas for the geometric designs of the jazz age. The 'Good Shopper' of this Empire Marketing Board poster, despite using a practical woven straw bag for her purchases, keeps her smart deco clutch tucked under her arm.

Sleek monochrome patterning and streamlined shapes filled the new department stores and materials as diverse as crocodile, antelope and new plastics such as Bakelite were used for bags. Dod Procter's circular geometric-patterned bag is instrumental in telling a story – the personal items strewn on the hall table allude to a late night with an unhappy ending, the discarded bouquet and open cigarette pack suggesting a figure just out of sight.

The Second World War meant a shortage of leather, zips and metal frames and with the new challenge of how best to conceal an ugly gas mask, bags grew in size. As Vogue confirmed in 1943: 'Big bags are best; they suit our mood for being self-sufficient.'

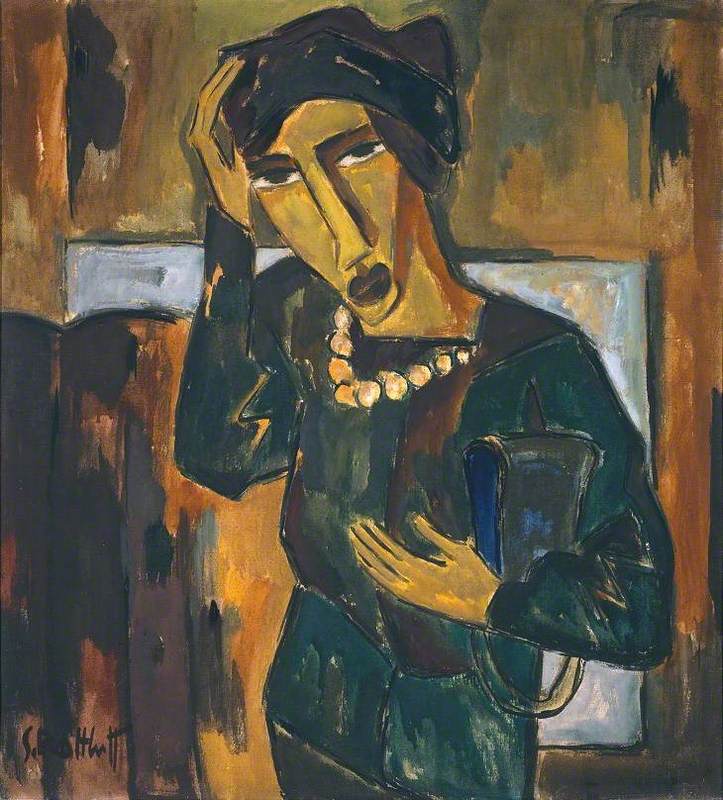

Many women embraced the spirit of 'Make Do and Mend', reusing existing frames to fashion new bags. This may explain the outsize frame of the sombre handbag in this 1944 painting. The bag suggests the gloom and restrictions of wartime while the bowl of primroses, to the foreground, speaks of fresh hope and a return to colour.

Once Hermès had named a bag after film star Grace Kelly in the 1950s, and bags were created for Audrey Hepburn and Sophia Loren, public interest intensified and the 'it' handbag was elevated to luxury item status.

Though on the ordinary street the rigid handbag with a clasp closure was the choice of many women, the youthquake of the 1960s challenged existing norms, creating shockwaves with its miniskirts and bags with long swinging straps in vinyl, chainmail and shiny patents, inspired by Op Art and space travel. Meanwhile freewheeling hippies slung soft suede or patchwork bags over their shoulders.

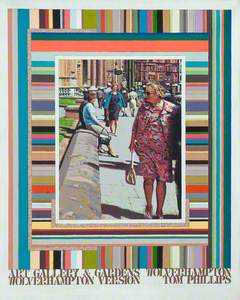

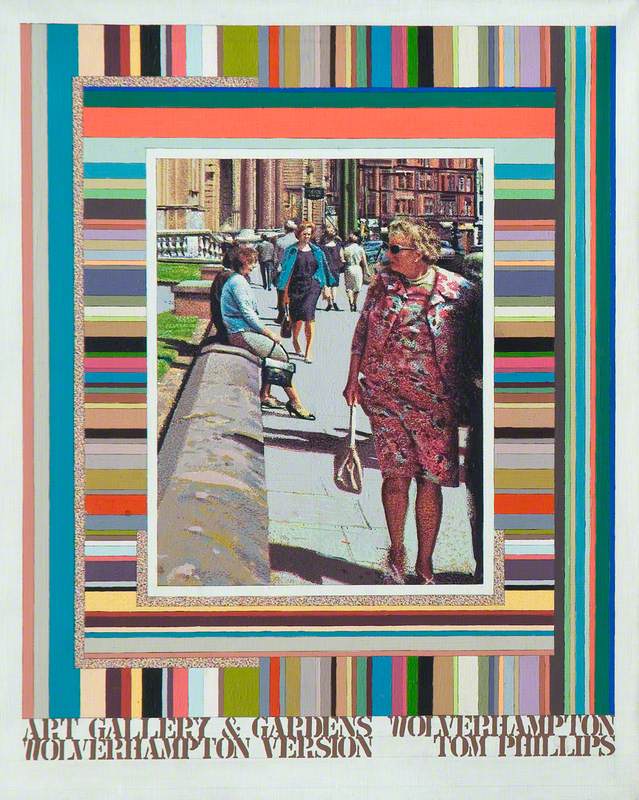

Art Gallery and Gardens, Wolverhampton

(left panel) 1970

Tom Phillips (1937–2022)

The classic framed handbag gained political status in the 1980s in the hands of Margaret Thatcher, Britain's first female Prime Minister. Thatcher was known to fish in her bag during a meeting for a piece of paper that would have valuable advice on it.

Ministers feared the bag's contents, with Robert Armstrong, Cabinet Secretary, remarking: 'The art of being a successful cabinet minister was to have worked out in advance how you shot down the advice that was in her handbag, and if you did it well enough the handbag was not opened.'

The fearsome handbag spawned the word 'handbagging', defined as a put-down from a female politician, and caused controversy among some for its absence from the statue of Thatcher that now stands in the Houses of Parliament.

Recent decades have seen the unisex tote bag used to promote brands, make political statements or carry campaigning slogans (such as the Art Matters bag in the Art UK Shop), while the relentless proliferation of the designer handbag, whether real or counterfeit, continues unabated.

There is however one bastion of continuity – the Queen's handbag. Comfortingly timeless in its many colours and iterations, Queen Elizabeth's handbag, from traditional family company Launer, sits firmly on her arm at every occasion. It even inspired a sculpture by chainsaw artist Andy Hancock for the Queen's Golden Jubilee in 2002, which is adorned with anodised tags stamped with the initials of members of the public.

Despite the fact that so many of us now need a backpack to carry all the paraphernalia of modern life around, the handbag has, if anything, garnered more interest than ever in recent times.

For many, it is the most desirable of all accessories and has provoked extraordinary creativity among designers. As Lucia Savi, curator of the forthcoming V&A exhibition 'Bags: Inside Out' emphasises: 'Designers have long played with this idea that bags are like sculpture.'

Perhaps we should look at our own bags in a new light.

Lucy Ellis, freelance writer

'Bags: Inside Out' opens at the V&A in early December 2020 (restrictions permitting)

Further reading

Aileen Ribeiro, The Gallery of Fashion, National Portrait Gallery Publications, 2000

Meredith Etherington-Smith and Caroline Clifton-Mogg, The Secret History of the Handbag, Double-Barrelled Books, 2014

Claire Wilcox, Bags, V&A Publishing, 2008

.jpg)