The most famous post-war 'definition' of sculpture has it that 'sculpture is what you bump into when you back up to look at a painting'. Usually attributed to American abstract painter and wit Ad Reinhardt (1913–1967), it was no doubt partly prompted by the frustration many modern painters feel when they have to share gallery space with large sculptures that may upstage their paintings – the earliest being Monet, who fell out with his great friend Rodin when The Burghers of Calais was parked in front of his paintings at a joint gallery exhibition in 1889.

Burghers of Calais

1884–1889 & 1914

Auguste Rodin (1840–1917) and Alexis Rudier

But more often than not painters have learned a huge amount from sculpture, and any rivalry they may feel with sculptors is an intensely creative one. This is made abundantly clear from the Art UK website, with its wealth of paintings that include depictions of sculpture. The sculptures are not there simply as decorative fillers and background, but to stimulate eye and mind. To borrow a phrase coined by anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, sculptures are 'good to think with'.

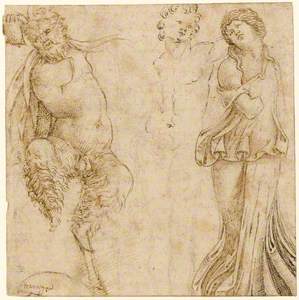

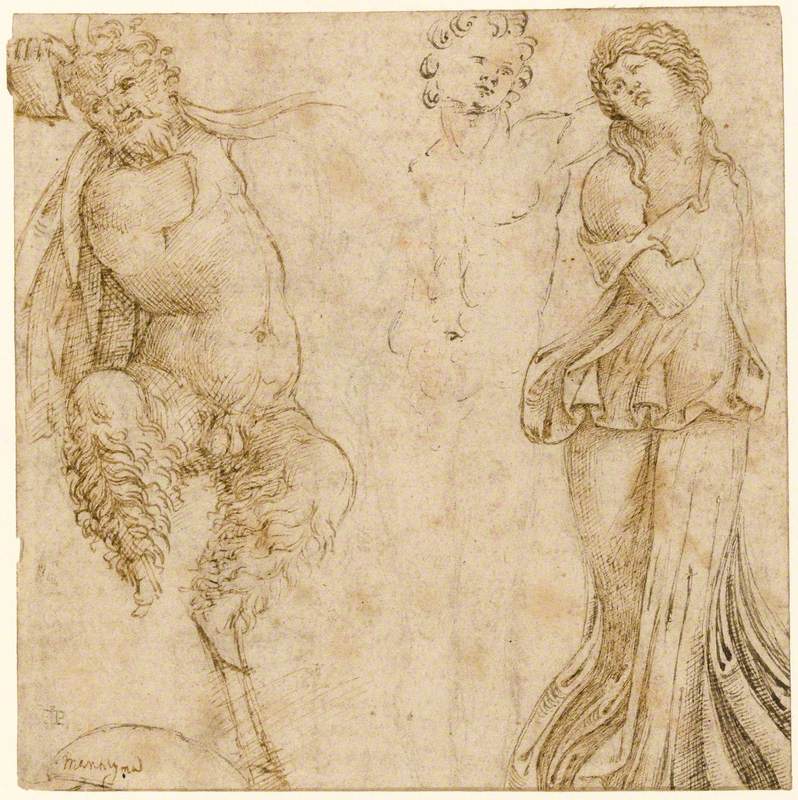

Antique sculpture was a major inspiration for artists from the Renaissance until the nineteenth century, and one of the great pioneers in its rediscovery was the Bolognese painter and occasional sculptor Amico Aspertini (1474–1552). He is best known for a series of sketchbooks crammed with drawings of antique sculpture made in Rome in around 1500, and again in the 1530s.

Despite Aspertini's importance, he has only recently recovered from Vasari's hatchet job in the Lives of the Artists, where he is portrayed as a crackpot who painted at lightning speed with both hands (the 'chiaro' in one, the 'scuro' in the other!). Vasari may have been responding adversely to the sinuous intensity of works like the Virgin and Child between Saint Helena and Saint Francis (c.1520), acquired by the National Museum of Wales, Cardiff in 1986, and the only major Aspertini in the UK. He is now admired as an innovative precursor to Mannerism.

Virgin and Child between Saint Helena and Saint Francis

c.1520

Amico Aspertini (1475–1552)

Aspertini's painting is divided into three horizontal bands. He creates intriguing counterpoints between the central trio of monumental painted saints; an evanescent stormy landscape background with buffeted ghostly figures; and the intricately crowded sculptural relief along the bottom that resembles an antique sarcophagus.

Freestanding marble statuettes are arranged before a marble ledge on the which the saints lean, and on which the fidgety Christ child stands: on the left, we see Moses receiving the tablets with the commandments, then smashing them after he finds the Israelites worshipping the Golden Calf; on the right, we see the story of the Biblical King Josiah destroying the idols.

Paradox is piled on paradox. Why did this Bolognese lover of antique sculpture devise fictive sculpture depicting stories that celebrate the destruction of sculpture? Aspertini is trying to express a powerful yet complex idea: that Christianity both superseded and absorbed the world of classical antiquity. Antiquity had first to be destroyed and buried before it could be reborn. Imperial Rome and its temples became the foundation for Papal Rome and its churches; the Popes now owned the finest collections of antique sculpture.

Astonishingly, Christ's legs are in the same position as those of the smashed statue of a dancing satyr displayed on a pedestal, and his skin is marmoreal. The visual quotation shows that Christian dances of spiritual joy have superseded carnal pagan dances; it also poignantly reminds us that Christ, even more fragile than a marble statue, would be 'broken' on the Cross.

The most celebrated antique sculpture in the papal collections depicted the Trojan priest Laocoon and his two sons being attacked by sea snakes sent by vengeful gods.

The original was dug up in Rome in 1506. Laocoon became a standard model for depictions of martyrs, and so moving was the statue that the Venetian writer Anton Francesco Doni wrote that when a spectator sees it, he is so overcome by compassion that he feels bitten by the same snakes and compelled to adopt the same pose, and to writhe in agony.

It is seen here (in reverse) in a semi-wild landscape by Dutch artist Abraham Begeyn (1637–1697), their poses echoed by the twisting oak trees: even nature feels sympathy, but not the bathetic goats.

Landscape with Goats and a Marble Sculpture of Laocoön

Abraham Begeyn (1637/1638–1697)

The soulful sitter in Jacopo Palma il giovane's haunting Portrait of an Artist performs sympathetic mimicry with his own sculpture collection.

Portrait of an Artist

(possibly Antonio Vassilacchi, called 'L'Aliense') c.1600–1620

Jacopo Palma il giovane (1544/1548–1628)

His head sharply tilts over in such a way that it mirrors the bust head of the short-lived, sybaritic Roman emperor Vitellius to his left, and that matches the drooping head of Saint Sebastian to his right (a work by the leading venetian sculptor, Alessandro Vittoria).

Palma was the leading religious painter in Venice after the death of Titian in 1576. The identity of the sitter is much debated, but it is likely to be an artist rather than a collector as the sculptures are plaster casts, which were becoming essential props in artists' studios and academies. The Greek-born venetian painter Antonio Vassilacchi, known as Aliense (1556–1629), has been proposed. He was a friend of Palma's and had a significant cast collection. This might also explain the white curlicue highlight on the sheet of paper – similar calligraphic curlicues are found in Aliense's drawings.

The sitter is not just surrounded by famous examples of melancholy and martyrdom (Vitellius was murdered in Vespasian's coup; Saint Sebastian was tied up so he could be shot at by archers). There is also a contrast between Christian and pagan figures. Saint Sebastian is located to the sitter's right, traditionally the side of virtue, and of the 'saved' in Last Judgments; Vitellius is on the left, the 'sinister' side – reserved for the damned. The sitter leans, and is orientated, towards the right. So the sculptures are being used to tell a story about moral as well as aesthetic choices.

The use of sculpture to instruct becomes increasingly common in the following centuries, and nowhere more compellingly than in English artist Isaac Fuller's self portrait with his son (c.1670).

Fuller (1606–1672) trained to be a printmaker in France, and then worked as a portrait and history painter in Oxford and London. This is a pioneering example of an English artist trying to make a portrait with a dramatic and intriguing narrative.

Fuller lived a dissolute bohemian lifestyle (the play of rippling reds and golds gives him a feverish molten quality), but here he uses sculpture to persuade his son not to copy his behaviour. His right hand gently cradles a cast of the startled head of the Medici Venus, who epitomised 'modest' nudity because her hand hid her sex from peeping toms.

Fuller's left hand grabs the head of a bronze satyr as if to hide and suffocate him. He's saying – 'now my boy, don't ravish or lust after women like a satyr – protect and cherish them'.

But the odds are long in the age of Charles II. That's why Fuller looks tearful – he knows a restrained lifestyle is wishful thinking.

During the eighteenth century, the opportunities afforded by the Grand Tour – a cultural pilgrimage to Italy – meant that wealthy Englishman were able to acquire antiquities, many newly excavated. The English, with their expanding empire, saw themselves as heirs to the Romans, and so they liked to surround themselves with Roman busts and statues.

The German-born portrait and theatrical painter Johann Zoffany (1733–1810) painted the finest depictions of collectors and Grand Tourists looking at antique sculptures.

The Tribuna of the Uffizi

1772–1777, oil on canvas by Johann Zoffany (1733–1810)

In his witty masterpiece The Tribuna of the Uffizi (1772, Royal Collection) he shows a gaggle of Grand Tourists ogling the bare bottom of the Medici Venus, and Zoffany – a well known sybarite – depicted himself in a similar way in a late Self Portrait, with a cavorting antique couple in the background.

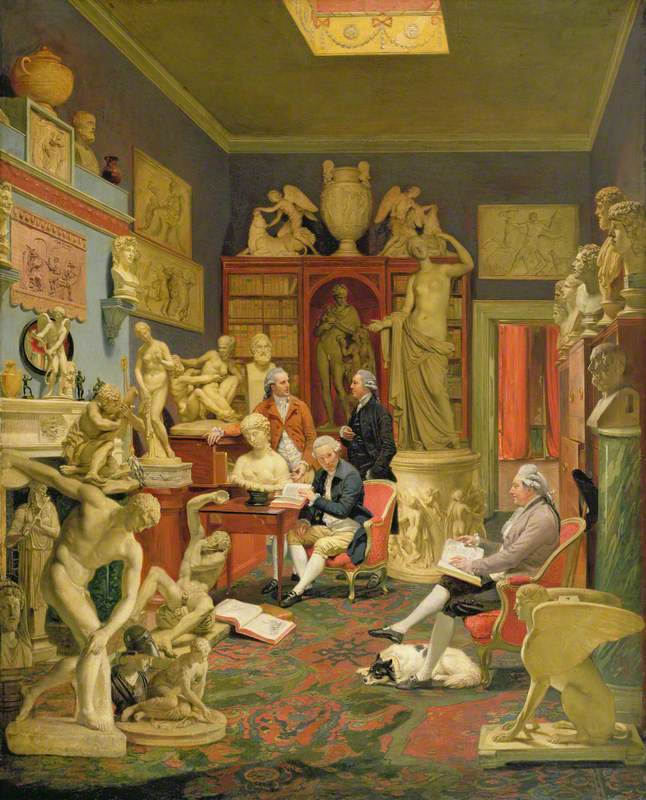

But in his celebrated portrait of Charles Townley and Friends in His Library at Park Street, Westminster (1781–1790 & 1798), serious connoisseurship and chastity are to the fore.

Charles Townley and Friends in His Library at Park Street, Westminster

1781–1790 & 1798

Johann Zoffany (1733–1810)

Townley (1737–1805) was a Catholic landowner and major collector who made three Grand Tours. He was a trustee of the British Museum, and his heirs sold his collection to the museum for a very reduced price. He sits soberly in the foreground with a big antiquarian book on his knees, at a measured scholarly distance from his beloved antiquities. No sublime transport or palpitation here.

His favourite, the demure bust of the chaste nymph Clytie, who was turned into a flower for her unrequited love of the sun god Helios, sits unobserved on the desk.

Clytie or Antonia @britishmuseum #Townley & http://t.co/fvEFAg7ekG @Your_Paintings #Zoffany http://t.co/I7I79Qidq5 pic.twitter.com/hq5Zvo9aSQ

— Tania Adams (@adams_tga) September 5, 2015

This was the only sculpture Townley took with him when he fled the anti-Catholic Gordon riots of 1780, and Zoffany's picture records his – and the collection's – narrow escape.

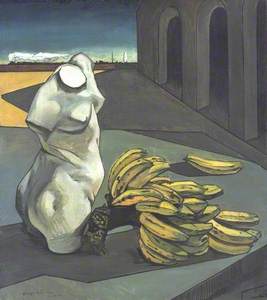

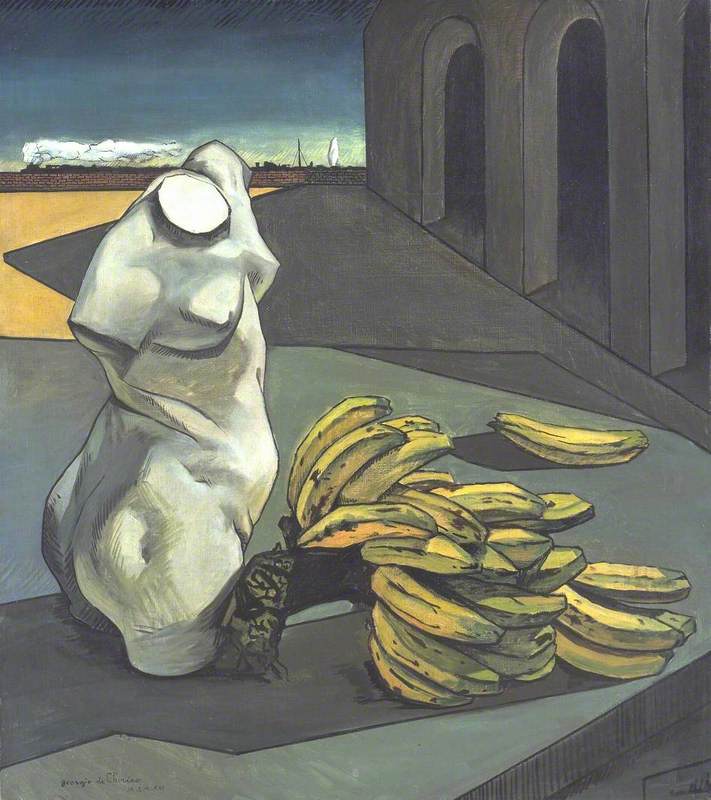

In the twentieth century, antique sculpture was often derided for its supposed insipidity and unnaturalness rather than revered as an ideal. But its newly marginalised, alien status has been dramatised to brilliant effect. The great pioneer is the Greek-born Italian painter Giorgio de Chirico (1888–1978), who was feted by the Surrealists.

In The Uncertainty of the Poet (1913) a fragmentary torso of Aphrodite (Greek goddess of love) is mysteriously juxtaposed with a bunch of ripe bananas in an arcaded square strafed by dark shadow, with a passing steam train and ships in the background. Aphrodite's thigh brushes the bunch of bananas, as though there is – at some basic fruity level – a shared sensuousness. But poetic uncertainty rules: time (and place) is out of joint, and the goddess of love is a piece of flotsam and jetsam, no longer worshipped.

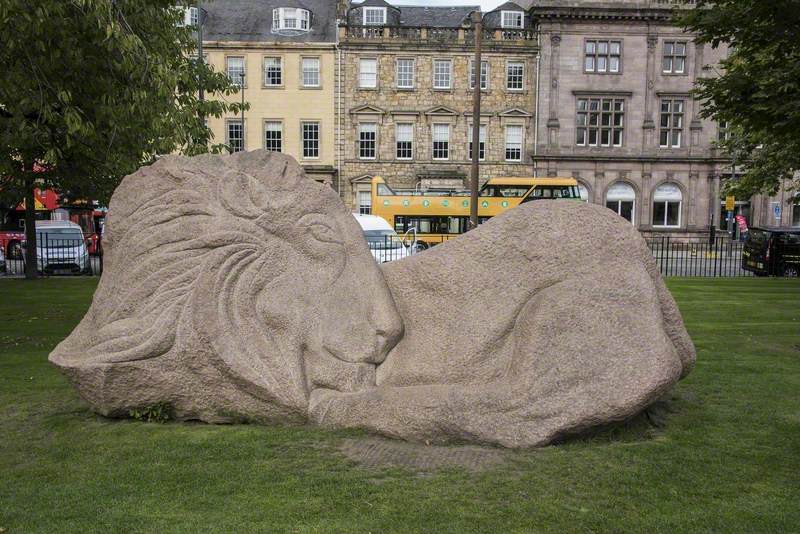

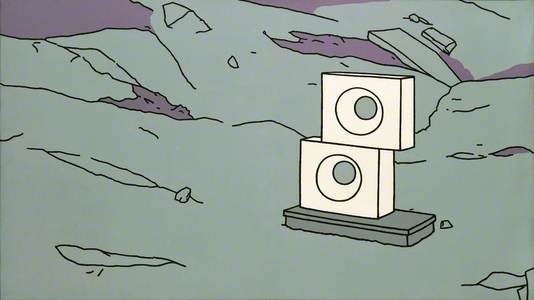

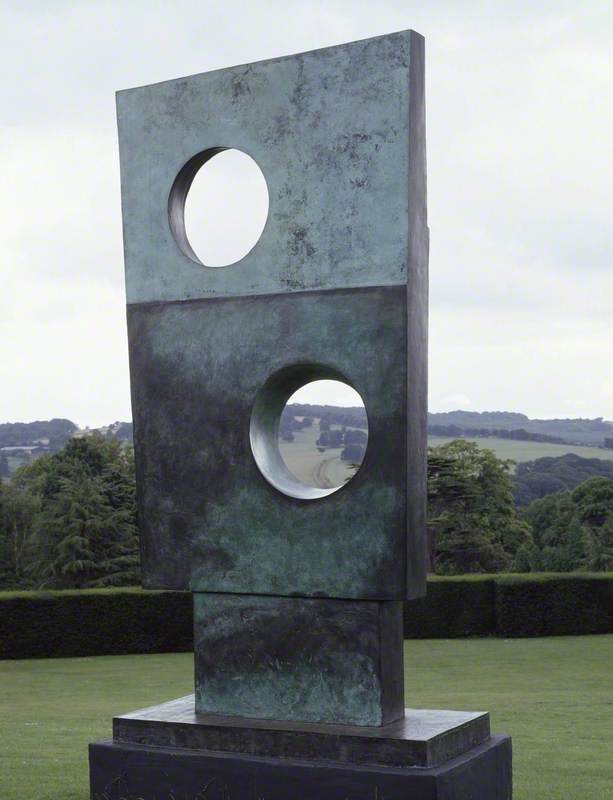

Enigma is also central to English painter Patrick Caulfield's work, and nowhere more so than in Sculpture in a Landscape (1966).

Caulfield (1936–2005) coincided with Pop art, and his graphic terseness does resemble modernist cartoons and advertisements, but rather than revelling in modernity he underlines its strangeness. Here two Barbara Hepworth style abstract sculptures – inspired by Squares with Two Circles (1963) – have crash-landed in a desolate looking rocky landscape.

Hepworth always varied the size and position of the holes in her sculptures, but here they are identical, and they soon seem like a pair of alien eyes ogling us. This tells a larger truth: that in painting, sculpture always looks back at humanity – judging, testing, provoking.

James Hall, art critic, historian, lecturer and broadcaster

James is Research Professor at the Winchester School of Art, University of Southampton, and author of The Self-Portrait: a Cultural History (Thames and Hudson).

.jpg)