Among the grand paintings and furniture of Castle Coole – the imposing neoclassical one-time seat of the Earls Belmore on the outskirts of Enniskillen – it's easy to overlook this marble figurine of an elephant standing on a plinth and carrying an obelisk on its back.

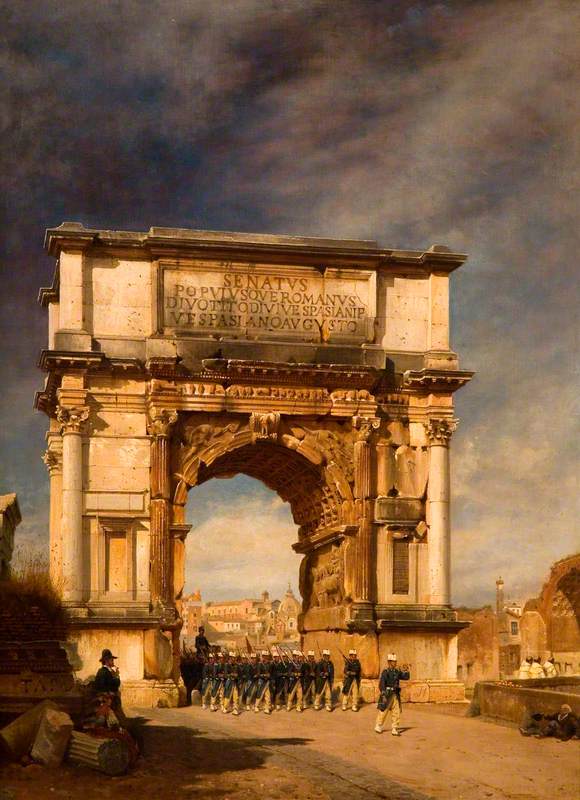

Probably early nineteenth century, it represents the elephant statue of the Piazza della Minerva in Rome, one of the Eternal City's more curious monuments. I suppose that the first or second Earl Belmore brought it back to Ireland as a high-class souvenir of a grand tour of Italy – the British aristocracy's equivalent of a gap year.

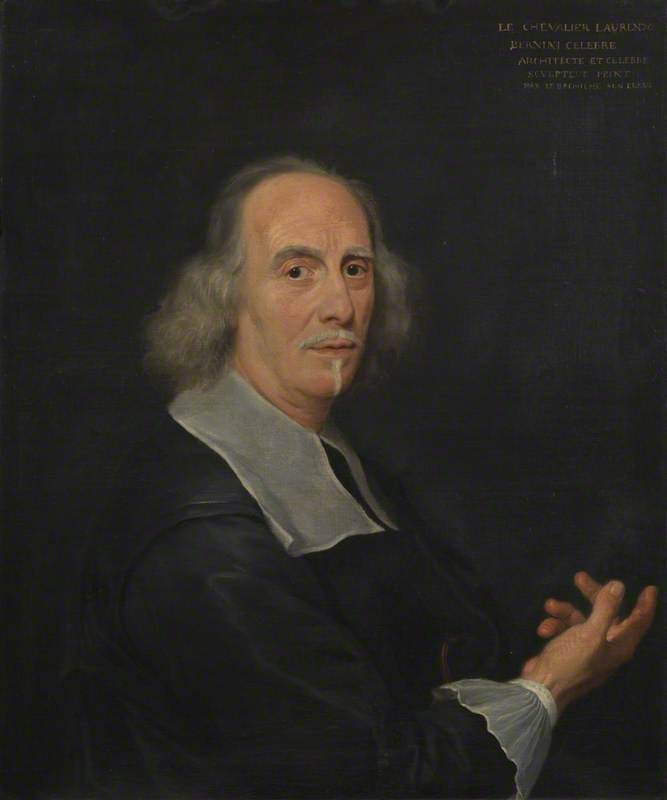

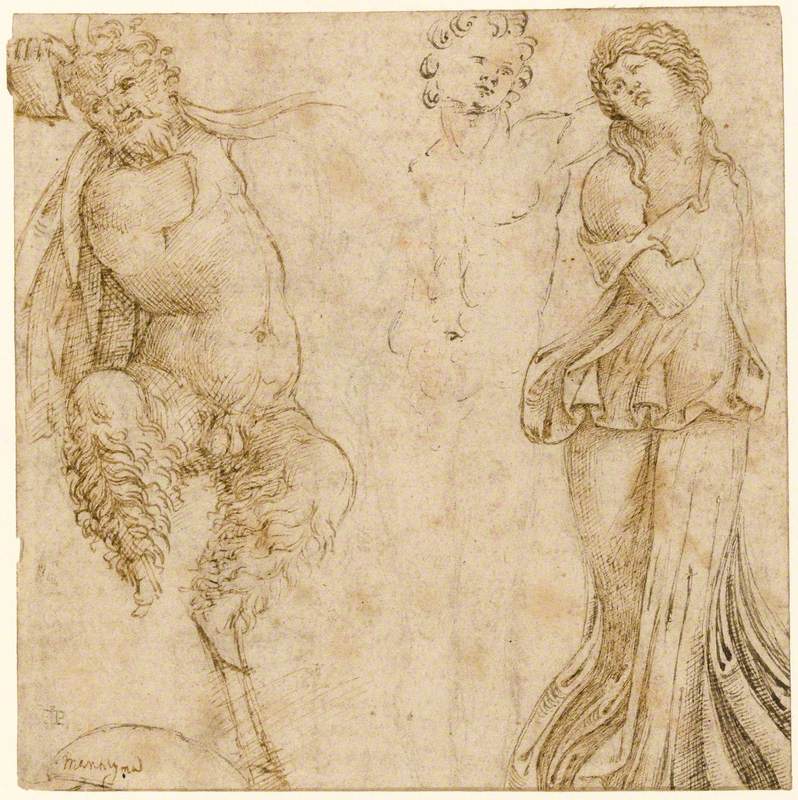

The original elephant in Rome was designed by Gian Lorenzo Bernini (1598–1680) and executed under his direction by Ercole Ferrata, one of the many talented assistants in Bernini's employ. Bernini is not especially well represented in either private or public collections in the UK, with the outstanding exception of the Royal Collection, which has a number of very significant drawings by him.

In the same period as Rembrandt, Rubens and Velázquez, Bernini was without question the most sought-after artist in seventeenth-century Europe and his talents were well employed and also jealously guarded by a succession of popes. So desirable was Bernini that Louis XIV of France bullied Pope Alexander VII into lending him the artist for a brief working holiday in Paris. It was, by the way, a disaster. The French didn't like Bernini's ideas for the new Louvre palace and Bernini just didn't like the French.

Rome is indelibly stamped with Bernini's genius. The Baldacchino, or great canopy, over the high altar at Saint Peter's, Saint Peter's Square itself, the heart of Vatican City, the great mythological sculptures of the Borghese Gallery, and Rome's most beautiful fountain in Piazza Navona are familiar to visitors to Rome, even if Bernini himself is hardly a household name.

A Capriccio with Bernini's Central Fountain on the Piazza Navona, Rome

Johannes Lingelbach (1622–1674) (attributed to)

Bernini has been described – quite rightly I think – as 'the genius of the Baroque' – and this may be why he isn't so well known in Britain. British taste was very much against the Baroque, which was regarded as suspiciously Catholic and smacking of absolutist continental politics. Of course, an English Baroque style of architecture developed – Blenheim Palace is probably the best example – but English Baroque is positively restrained and well mannered compared to the exuberance of Bernini and his contemporaries.

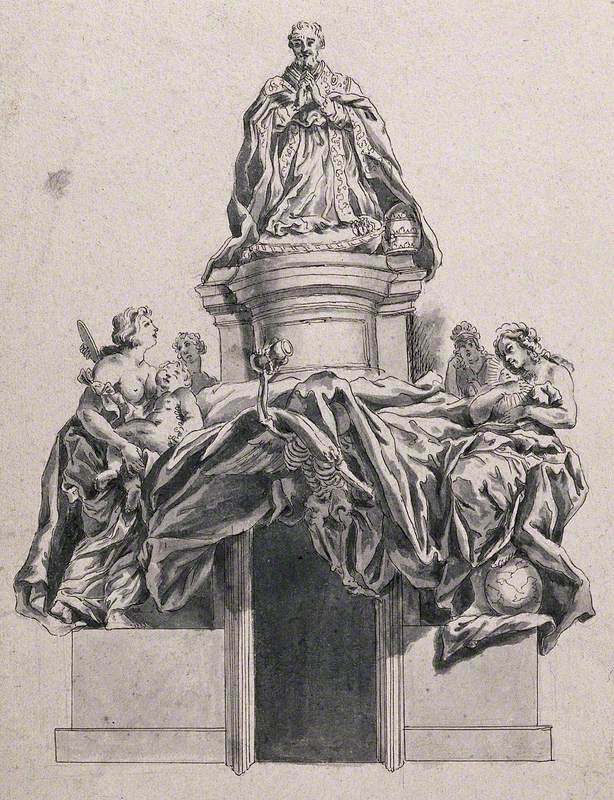

The elephant of the Piazza Minerva has a distinctive history, beginning when some workmen in the next door Dominican monastery unearthed an ancient Egyptian obelisk brought to Rome as a trophy sometime in the first or second centuries. Obelisks were highly prized objects and the Pope commissioned Bernini to derive a suitable setting for it.

Pope Alexander VII was a great intellectual and no doubt pleased when Bernini came up with a design based on an illustration from a much loved and extraordinarily hard-to-understand Renaissance fantasy, Hypnerotomachia Poliphili. Bernini's team went to work and the Pope involved himself in the composition of an elaborate Latin inscription for the base of the monument reminding the public – at least those members of the public who could read Latin – that 'it takes a robust mind to carry solid wisdom', an obvious tribute to the learned Pope, whose coat of arms decorates the elephant's plinth.

Alas, the Pope died a few weeks before the monument was unveiled. You may ask now, why an elephant to pay tribute to a Pope? There are a few reasons. Throughout the seventeenth century, a number of elephants toured Europe as popular attractions and the novelty of these great beasts gripped the public imagination. Perhaps more importantly, in an age that was in love with symbolism and allegory, elephants were prized for their reputed wisdom and supposed chastity and often used as representations of religion. So for a Pope whose modesty led him to turn down the offer of a portrait statue, an elephant was a perfectly good memorial.

Loyd Grossman, author and broadcaster

Loyd's book An Elephant in Rome: Bernini, The Pope, And The Making Of The Eternal City (2020) is published by Pallas Athene

An Elephant in Rome: Bernini, The Pope, And The Making Of The Eternal City

2020, front cover of book by Loyd Grossman, published by Pallas Athene