Who has not experienced, while walking through a museum or an art gallery, the appeal of certain works on display? We are attracted to artworks in so many ways, whether to assess their material properties, to create an intimacy with the object or for the seemingly harmless pleasure of transgressing a rule.

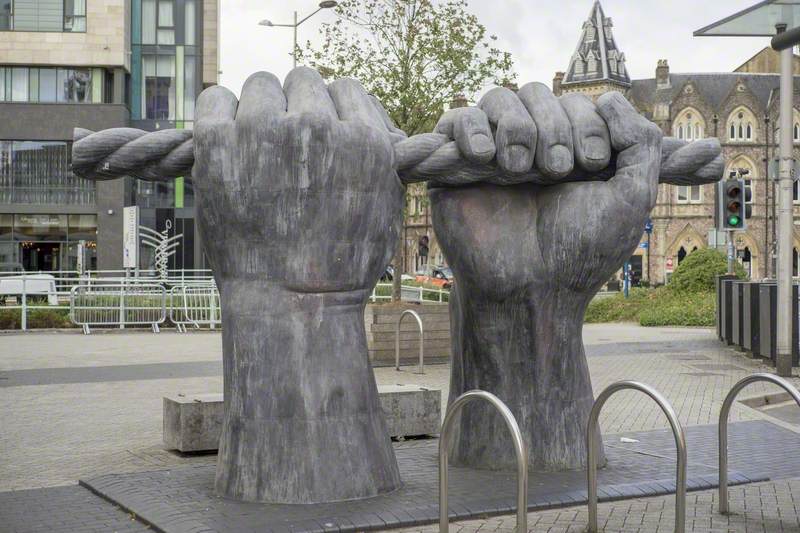

This is particularly true of sculptures.

Why the attraction? If I may invite you to rewind to the time when you were three years old, you might remember quite vividly the mental conflict that would seize you when faced with a lonely looking strawberry tart. The three-year-old may be at that breaking point where he knows that he could get in trouble if he were caught sticking his finger in the tart, yet the desire to taste, feel and risk something forbidden, would surpass the fear of the consequence of being caught. (This is generally why children are not permitted to visit museums alone.)

Deterrence in museums and galleries is a socially and physically constructed endeavour. As visitors, we are expected to respect certain etiquettes (no shouting, no running, no eating, and certainly no climbing or prodding!). But it’s interesting to recall that this is very much a modern and Western conception of how objects should be taken care of. Other cultures may have adverse arguments, defending that historically/symbolically/religiously significant objects should be available for social use. Moreover, before the 1850s in Britain, museums and cabinets of curiosities allowed all sorts of sensory interactions with objects, amongst which handling came as self-evident. Consider again a collection of musical instruments that cannot be heard! This would have been outright bizarre in early eighteenth-century London, as we know from the accounts of the German scholar and traveller Zacharias Conrad von Uffenbach.

There are implacable arguments against touching artworks: by touching we introduce dirt particles, body oils and perspiration onto an object’s surface. The oils can then attract dirt to linger, and acidic oils can also cause corrosion. Visitors wearing jewellery present an additional risk, as can easily be imagined. The repetition of small touches by a number of people over time quickly add up to irremediable damage, while a single misjudged movement can result in sudden destruction.

Curators and museum staff are therefore faced with a dilemma: their role is

In (and to some extent out) of museums, we have progressively created a sensory hierarchy that favours visual cognition. If you live in a large city, you may have noticed that many museums are attempting to reverse this trend. Collections offer hands-on exhibitions, ‘feely Friday’ activities or even events that mix music, food and drink. These activities remain circumscribed

The Art UK Sculpture project includes a number of programmes that aim at creating closer interactions between the public and sculptures. Sign up for our newsletter to be informed of activities near you.

Jessie Maucor, Art UK Photography Manager

Gallery images by Stefan Draschan. To see more of Stefan's images, go to his website.

The title of this blog was inspired by Constance Classen’s article, ‘Museum Manners: The Sensory Life of the Early Museum’, Journal of Social History, Vol. 40, No. 4 (Summer, 2007), pp. 895–914.