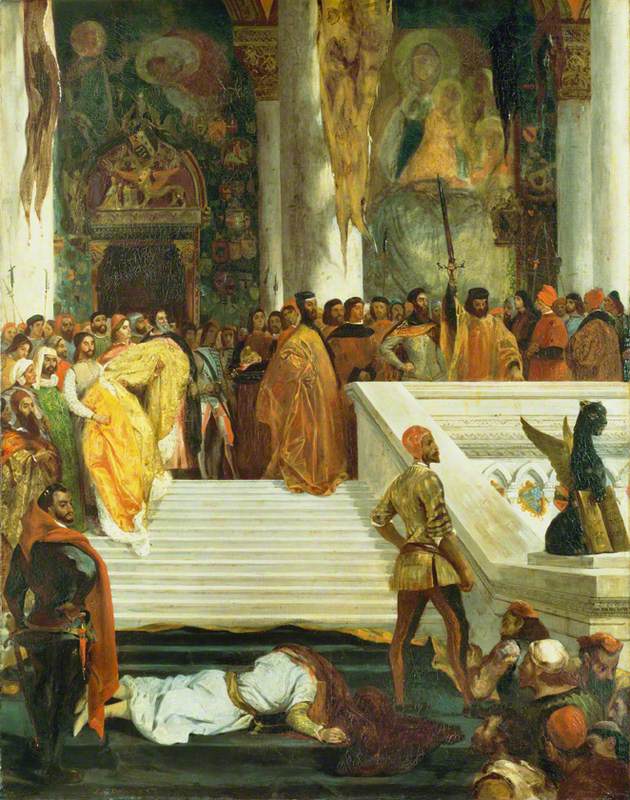

The Execution of the Doge Marino Faliero 1825–1826

Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863)

The Wallace Collection

(Born Charenton-St-Maurice, nr. Paris, 26 April 1798; died Paris, 13 August 1863). French painter, draughtsman and lithographer. He was one of the towering figures of the Romantic movement and one of the last major artists to devote a large part of his career to mural painting in the heroic tradition. Lorenz Eitner (An Outline of 19th Century European Painting, 1987) describes him as ‘the last great European painter to use the repertory of humanistic art with conviction and originality. In his hands, antique myth and medieval history, Golgotha and the Barricade, Faust and Hamlet, Scott and Byron, tiger and Odalisque yielded images of equal power.’ He was the son of a diplomat, Charles Delacroix, who at the time of his son's birth was ambassador in The Hague, but it has been suggested that his natural father was the great statesman Talleyrand, a friend of the family. His mother, Victoire Oeben, was the daughter of Jean-François Oeben, one of the most distinguished furniture makers of his day. Delacroix had a good education and grew up with a love of literature and music as well as art. In 1815 he began studying with Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, who had earlier taught Géricault (whose work greatly influenced Delacroix), and the following year he enrolled at the École des Beaux-Arts. His real artistic education, however, was gained by copying Old Masters in the Louvre, where he delighted particularly in Rubens and the 16th-century Venetian painters. Throughout his life he remained a keen and perceptive student of his predecessors, and Rubens—with his richness of imagination, warmth of colour, and enormous energy—was a constant source of inspiration. In 1822 his career was brilliantly launched when his first submission to the Salon, the Barque of Dante (Louvre, Paris), a melodramatic scene from Dante's Inferno, was the talking point of the exhibition and was bought by the state. Two years later he had another success at the Salon with the Massacre at Chios (Louvre), inspired by a recent Turkish atrocity in the Greek War of Independence. It aroused much hostile criticism (Gros, who had admired the Barque of Dante, called it ‘the massacre of painting’), but it was awarded a gold medal and once again was bought by the state (with Talleyrand perhaps pulling strings in the background).

In 1833 Delacroix received a commission to decorate the Salon du Roi in the Palais Bourbon (now the Assemblée Nationale), Paris, and from this point much of his career was devoted to large-scale wall and ceiling painting. He finished the work in the Salon du Roi in 1837 and followed this with decorations in the library of the same building (1838–47). His other major decorative schemes (all in Paris) include those in the Library of the Luxembourg Palace (1841–6), the Galerie d'Apollon in the Louvre (1850), and the Chapelle des Anges of the church of St Sulpice (1853–61), with its celebrated scenes of Jacob and the Angel and Heliodorus Expelled from the Temple. All these works are in oils (he only once experimented with fresco). In addition to these huge public undertakings, Delacroix continued to produce a wide range of smaller paintings, and he also made lithographs, the best known of which are his illustrations to Goethe's Faust (1828) and Shakespeare's Hamlet (1843). He was awarded many honours for his work, and his charm, intelligence, and dashing looks meant that he was in demand by fashionable society. However, he was fairly solitary by nature (he never married) and had only a few close friends, including another archetypal Romantic genius, Chopin, of whom he painted a portrait (1838, Louvre) and whom he described as ‘the truest artist I have ever met’ (he had a piano installed in his studio so the great man could play there).

Although he carefully trained the assistants he used on his decorative commissions, he otherwise had few pupils, and none of them attained any independent distinction. Nevertheless, he had enormous influence on a wide range of artists, particularly through his vibrant and uninhibited use of colour. He was ‘the supreme colourist of the first half of the nineteenth century’ (Lee Johnson, Delacroix, 1963), and the artists who were most clearly influenced by this aspect of his work include Monet, Renoir, and Seurat. Among those who copied his work and valued its liberating effect on the imagination were Cézanne, Degas, van Gogh, and Redon, and among the professed admirers depicted in Fantin-Latour's Homage to Delacroix (1864, Mus. d'Orsay, Paris) are Baudelaire, Manet, and Whistler.

Delacroix's output was enormous. After his death his executors found more than 9,000 separate works in his studio, including several hundred paintings and more than 6,000 drawings. He drew every day, like a musician practising scales, and he prided himself on the speed at which he worked, declaring ‘If you are not skilful enough to sketch a man falling out of a window during the time it takes him to get from the fifth storey to the ground, then you will never be able to produce monumental work.’ Delacroix also left behind a substantial literary legacy, for few other great painters have written so copiously or so interestingly about art. He was a voluminous letter writer and kept a journal from 1822 to 1824 and again from 1847 until his death—a wonderfully rich source of information and opinion on his life and times. His studio in Paris is now a museum devoted to his life and work, but the Louvre has the finest collection of his paintings.

Text source: The Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists (Oxford University Press)