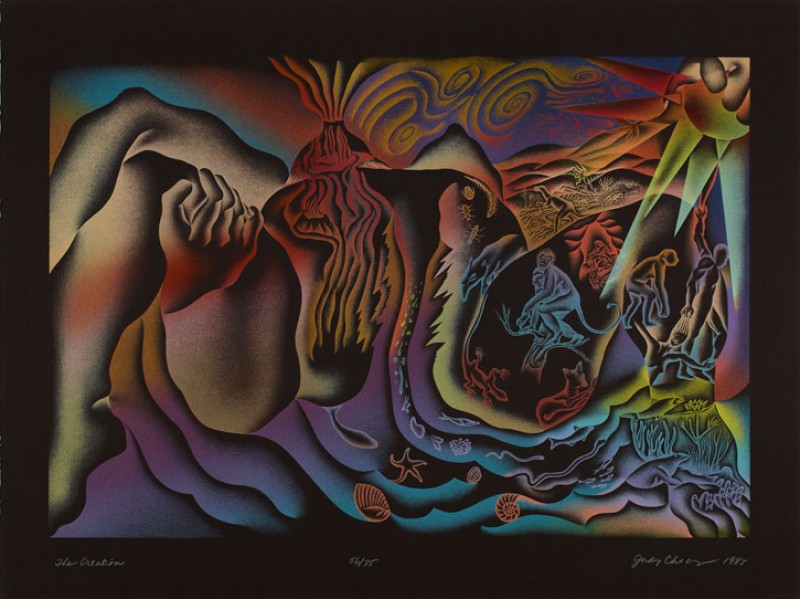

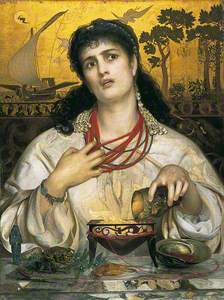

The anguished figure of Medea is the subject of Frederick Sandys' painting of 1868. The enchantress tears at her beaded necklace while concocting a poisonous potion, with which she will use to commit murder.

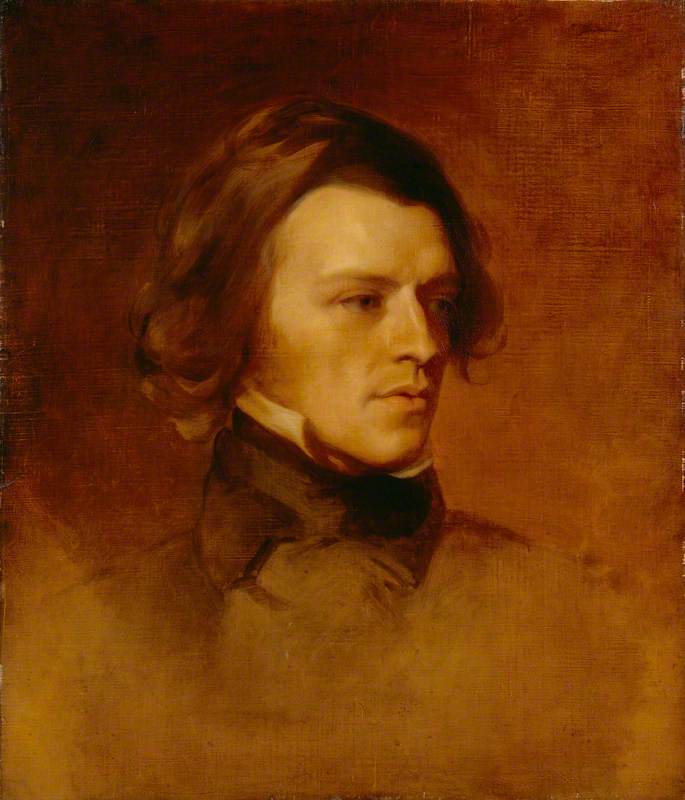

An artist affiliated with the Pre-Raphaelites, Sandys submitted his work to the Royal Academy for display in the Summer Exhibition of the same year. Although agreed to be of quality, the painting was ultimately rejected, sparking controversy.

After its acceptance the following year, one critic writing for Art Journal claimed 'either by its merits or its defects, [it] certainly stands alone...' He predicted that Medea would be 'either vastly admired or supremely detested.'

Ambiguity remains as to whether Sandys' rejection was due to internal politics, or because his subject matter – a sorceress known for killing her own children – was deemed to be deplorable to members of the Academy. However the ambivalent responses to Sandys' painting reflect the historic divisiveness of the character of Medea – a woman so enraged by her deceitful husband that she commits the unthinkable. She is the ultimate embodiment of female vengeance and an archetype of the femme fatale.

Medea's tale has prompted artists to explore the following questions: did she kill her children in an impassioned fit of rage, or did she murder in cold blood? Should we regard her as an evil monstrosity? Or should she be humanised, as a wronged woman driven to madness?

Jason swearing Eternal Affection to Medea

1742-3

Jean-François de Troy (1679–1752)

Following the legend of the Golden Fleece, featuring the characters of Jason and Medea, the play Medea was written by the Greek writer Euripides and first performed in Athens in 431 BC. The Roman philosopher Seneca later adapted the tragedy in AD 50.

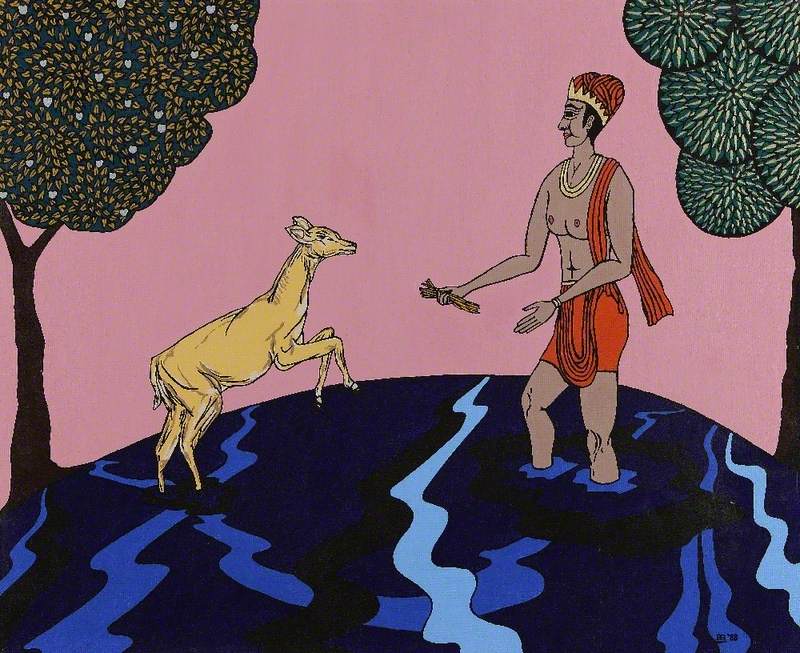

Medea was a princess of the barbarian kingdom of Colchis and the wife of Jason, leader of the Argonauts. Because she was a descendant of the Sun god Helios, Medea was not merely mortal, but possessed magical and prophetic powers. When she fell in love with Jason, she helped him to obtain the Golden Fleece from her father King Aeëtes, betraying her own family in the process (she killed her brother).

Jason Taming the Bulls of Aeëtes

1742

Jean-François de Troy (1679–1752)

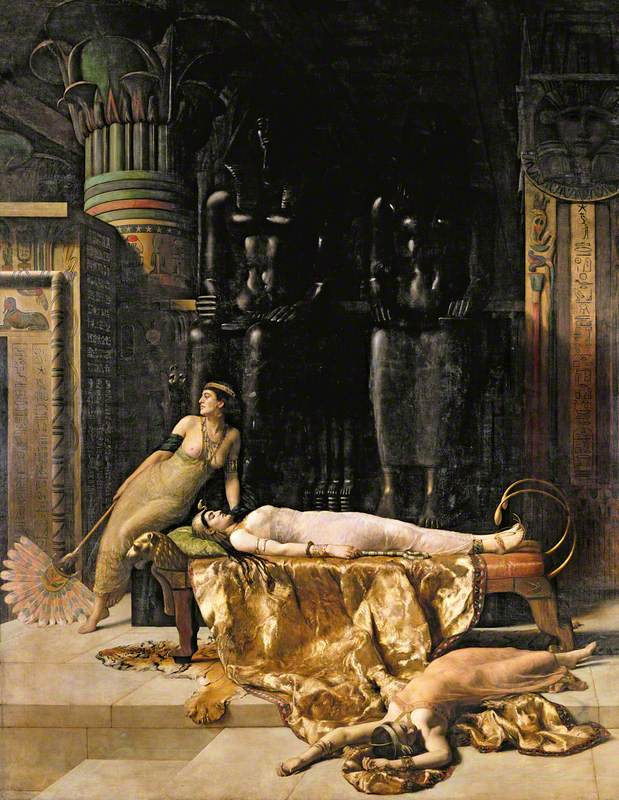

Medea lived in exile with Jason and their children in Corinth, until Jason betrayed her by marrying princess Glauce, the daughter of Creon, King of Corinth. He left Medea, who was disgraced by the affair. Medea's unquenchable desire for revenge against her husband led her to create a treacherous plot. She slyly pretended to support Jason's marriage, ingratiating herself to him, before murdering King Creon and his daughter. She also stabbed to death her children by Jason and, according to Seneca's version, tossed the bodies of her sons down the roof palace before fleeing Corinth in a chariot drawn by dragons.

An Episode from the Story of Jason and Medea

John Downman (1749–1824)

In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the story of Medea experienced a particular resurgence in literature and the dramatic arts, though as early as 1556, Étienne Jodelle's ballet proper Argonautes presented the character of Medea to the court of Catherine de Médici. The French playwright Pierre Corneille dramatised her tale in 1635, influenced by the texts of Euripides and Seneca. Many musical and operatic productions followed this, including adaptions by Francesco Cavalli (1649), Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1693), Antonio Caldara (1711), and notably, Handel, whose opera Teseo (1713) centred upon the vengeful character of Medea.

During the French revolutionary period, there were at least nine operas based on Medea, including Cherubini's of 1797. It has been suggested that Medea stood as a metaphor for the spirit of the French Revolution itself. In the German-speaking world, the tale inspired countless dramatists including the Austrian Franz Grillparzer who, according to historians, used Medea to launch a 'serious study in the victimisation of both womanhood and the outsider.' Grillparzer's Medea doesn't commit infanticide out of revenge, but to prevent her children from meeting a doomed fate.

Among artists, Medea was a popular mythological subject in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, during which time she was typically presented as an allegorical, feminine seductress, though in many different guises.

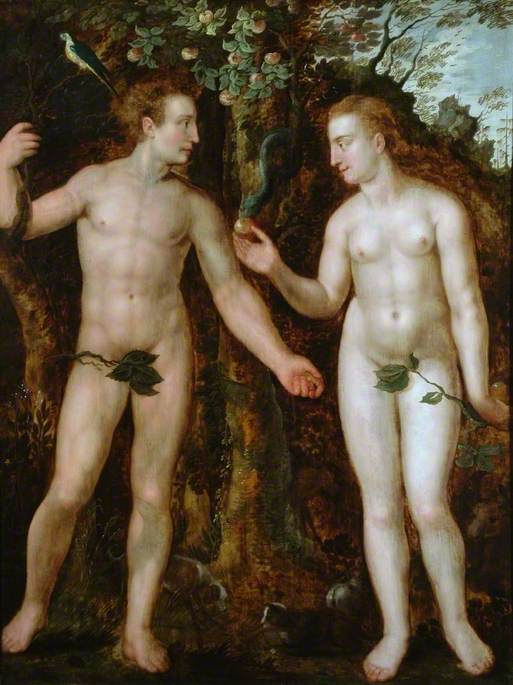

Around 1600, Peter Paul Rubens (1577–1640) created his ink drawing The Flight of Medea (in The Getty), followed by Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1654) who, in 1620, radically depicted Medea in the moment of killing her son (in a work now in a private collection).

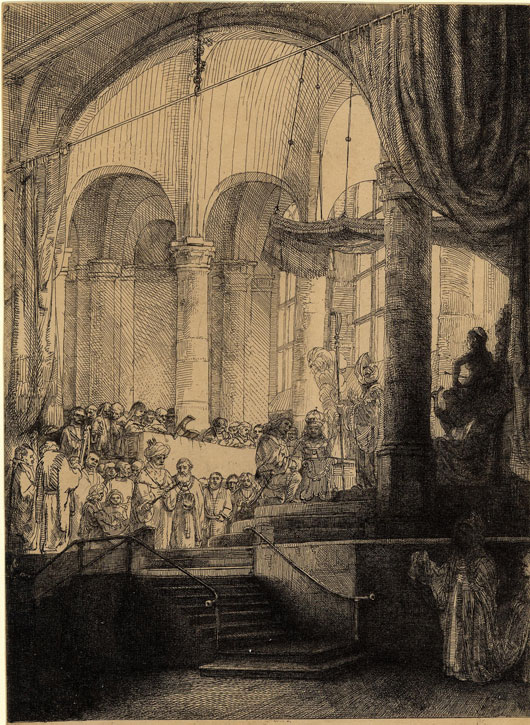

In 1648, Rembrandt (1606–1669) created the etching Medea, or The Marriage of Jason and Creusa.

Medea Casting Spells among Ruined Sculpture

c.1673

Henry Ferguson (before 1655–1730)

Not long after, the artists Henry Ferguson (1655–1730), Corrado Giaquinto (1703–1765) and Giovanni Antonio Pellegrini (1675–1741) painted the mythical enchantress too.

In 1715, Charles Antoine Coypel created this striking study of Medea's countenance in pastel, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. The final painting was submitted to the Académie Royale in 1715, and depicted the climactic moment of Medea's tale, when she kills her children and escapes the wrath of Jason. It is likely that stage adaptions of the story influenced Coypel's version, which clearly has a dramatic flair.

Medea

c.1715, pastel drawing on paper by Charles Antoine Coypel (1694–1752)

By the nineteenth century, images of Medea appeared widely across Europe, and representations ambivalently emphasised her as a scorned sorceress, or wronged wife and mother.

Eugene Delacroix's most famous depiction of 1838, titled Medea About to Murder Her Children, offers a sexualised rendering. Medea appears to hover between the role of mother and murderess – she tentatively holds the dagger close to her sons who try to escape her clutches.

Medea About to Kill her Children (Medée furieuse)

1838, oil on canvas by Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863)

The German painter Anselm Feuerbach (1829–1880) depicted Medea in 1870 (now in Munich's Neue Pinakothek), followed by Valentine Prinsep (1838–1904) in 1888, and Evelyn de Morgan (1855–1919) in 1889.

In Prinsep's depiction, Medea calmly gathers poisoned fungi from a forest floor, which she will later use to poison Glauce (Jason's new bride) and her father. In her right hand, she holds a dagger, pointing to her eventual infanticide.

In De Morgan's portrayal, Medea wonders the marble halls of Ancient Greece, plotting her revenge against Jason. She holds a vial of purple potion. When De Morgan exhibited this painting for the first time at the New Gallery in 1890, she accompanied the work with a William Morris poem titled The Life of Jason.

'Day by day she saw the happy time fade fast away,

And as she fell from out that happiness,

Again she grew to be the sorceress,

Worker of fearful things, as once she was.'

In contrast to other depictions, De Morgan offers a more sympathetic interpretation of Medea, presenting her as a grieving and wronged woman, responding to her own misfortune.

In 1907, John William Waterhouse (1849–1917) presented Medea concocting a magical potion that will enable Jason to complete the tasks set out for him by her father King Aeëtes. Waterhouse presents Medea in a Pre-Raphaelite style. Artists associated with the Pre-Raphaelite movement shared a preoccupation with Tennysonian figures, often involving empowered female witches and enchantresses, all of whom are dangerously in control of their own sexuality.

Jason and Medea

1907, oil on canvas by John William Waterhouse (1849–1917)

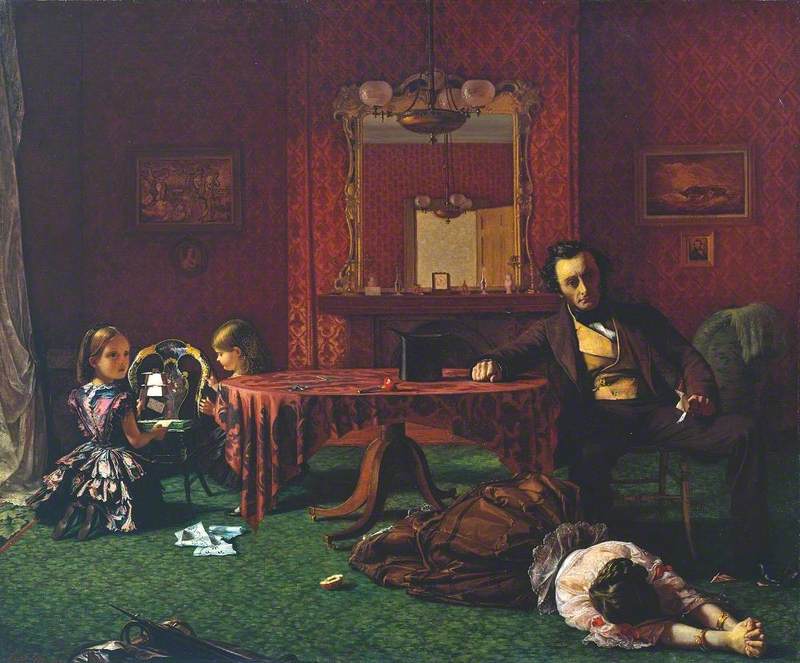

Historians continue to grapple with the resurgence of interest in Medea during the nineteenth century. Some have observed that representations of Medea in culture coincided with public debates about divorce laws and the enfranchisement of women in England. In 1857, the Divorce and Matrimonial Causes Act was passed, which allowed for separation on the grounds of adultery, cruelty, or desertion.

It seems plausible that Medea was appropriated for political and proto-feminist purposes, a vehicle to talk about social and political emancipation for women. For example, in 1856, Ernest Legrouvé opened his theatrical version of Medea to Parisian audiences, a man who would be known for supporting the women's movement and for publishing essays about the status of women in France. In 1868, the female writer and advocate of women's suffrage, Augusta Webster (1837–1894) translated Euripides' Medea in an attempt to promote the tale to British audiences.

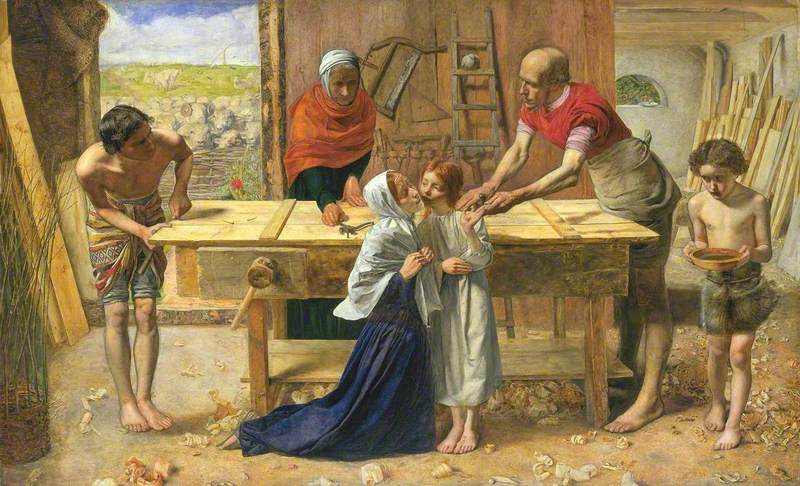

Medea also challenged preconceived notions about female sexuality. Christine Sutphin argues that mythological figures such as Circe and Medea countered the Victorian notion of female 'asexuality'. Against Coventry Patmore's conception of the 'Angel in the House' – a submissive and self-sacrificing wife who dutifully fulfils the expectations of her husband – Medea embodied a transgressive and deviant symbol of 'womanhood', which stood in contrast to the Victorian pure ideal.

By the twentieth century, the archetype of Medea expanded beyond being a symbol of female expression, though she continued to represent discourses to do with gender. Notable filmmakers, from Pier Paolo Pasolini to Lars von Trier have adapted her tale for their own cinematic purposes. In Pasolini's 'Marxist' rendering of Medea (1969), the opera singer Maria Callas stars as the powerful enchantress (though she doesn't sing).

An enduring and powerful symbol of female rage, Medea's story has stood the test of time – it has been adapted and weaponised according to each century's defining socio-political characteristics. Consistently, the story serves a warning against betrayal, reminding us of its corrupting nature, aptly worded in Euripides' drama:

'I understand too well the dreadful act I'm going to commit, but my judgement can't check my anger, and that incites the greatest evil human beings do.'

Lydia Figes, Content Editor at Art UK

Further reading

Maria Berbara, '15 Visual Representations of Medea's Anger in the Early Modern Period: Rembrandt and Rubens', Discourses of Anger in the Early Modern Period, 2015

Deborah Boedecker, Medea: Essays on Medea in Myth, Literature, Philosophy, and Art, Princeton University Press. pp.127–148

Edith Hall, Fiona Macintosh and Oliver Taplin, Medea in Performance 1500–2000, University of Oxford, 2000

Madison Skye Lauber, 'The Murdering Mother: The Making and Unmaking of Medea in Ancient Greek Image and Text', Bard College, 2018

Betine van Zyl Smit, 'Medea the Feminist' Acta Classica, Vol. 45, 2002, pp.101–122