'About suffering they were never wrong,

The old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position: how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along'

From W. H. Auden's Musée des Beaux Arts (1938)

At the end of 1938, as Europe descended inexorably into the chaos of war, W. H. Auden visited the Musée des Beaux Arts in Brussels. What he saw there, The Census at Bethlehem by Pieter Bruegel the elder, gave him a sense of perspective. Bruegel reminded Auden that hope can spring amidst indifference to suffering, and that, whatever happens, life somehow goes on.

Auden's experience is a telling example of why we should look at the Old Masters. Bruegel, like Rembrandt and Velázquez, can help us to make sense of human existence, with all its hopes and the fears. Their paintings may be objects of great beauty, but they are often more than the sum of their beautiful parts.

The Census at Bethlehem

1566, oak on panel by Pieter Bruegel the elder (c.1525–1569),

Even if at first glance Bruegel's painting is a Flemish winter scene, The Census at Bethlehem is, of course, a religious subject, albeit mixed with social commentary. Images have always played an important role in the instruction of the Christian faithful, and many Old Master paintings – and here I include all high-quality European works painted on canvas, panel or similar supports between about 1200 and 1900 – were produced as objects of devotion. In today's museums, divorced from this function, they are drained of all symbolic power. No longer eliciting our unquestioning adoration, they may even seem irrelevant, completely at odds with contemporary values.

Exhibitions featuring household names like Michelangelo and Monet can still attract hundreds of thousands, and 'lost masterpieces' like the Salvator Mundi command astronomical prices, but British visitors to permanent collections like The National Gallery's have suffered huge drops in recent years.

The Virgin and Child with Saints Dominic and Aurea

about 1315

Duccio (c.1255–before 1319)

So why should we – regardless of our beliefs about religion and taste for the contemporary – keep looking at paintings like The National Gallery's Virgin and Child by Duccio and Winter Landscape by Caspar David Friedrich?

My first answer relates to what they bring us as human beings.

As the art historian David Davies says about Velázquez's An Old Woman Cooking Eggs in Edinburgh:

'Since each object is observed and recorded with intense concentration, each has a separate identity and intrinsic value... a mundane subject of an old woman cooking two eggs is transcended and the contemporary beholder is made aware of the variety and complexity of the human condition'.

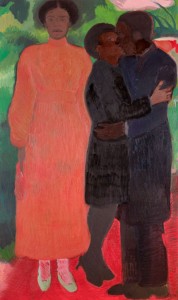

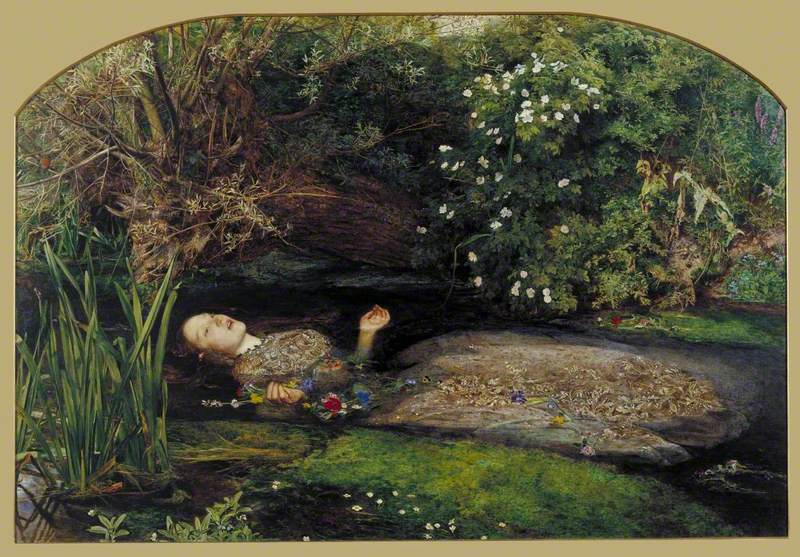

Old Master paintings can be immensely powerful. People cry before them and are calmed by them, perhaps because they remind us, like Millais' Ophelia, that we are not alone in suffering, and give us, like the Bruegel and Burne-Jones's Oblivion Conquering Fame in Birmingham, a sense of perspective.

Study of 'Oblivion Conquering Fame' (Troy Triptych)

1872–1875

Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898)

They can also make the ordinary, like A Lady Taking Tea painted by Chardin at the Hunterian, seem beautiful.

They are traces of human history, of daily life and customs throughout the ages, of extraordinary figures, and of people's hopes and fears as in John Martin's Solitude at the Laing.

They can reconnect us to nature, and, like Constable's many paintings of Hampstead Heath, tell us what the natural world looked like in past centuries.

Salome receives the Head of John the Baptist

1607-10

Caravaggio (1571–1610)

Works like Caravaggio's Salome receives the Head of John the Baptist and Artemisia Gentileschi's Self Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria give us insights into human psychology, identity and emotion in ways which can be more immediate than words.

Self Portrait as Saint Catherine of Alexandria

c.1615–1617

Artemisia Gentileschi (1593–1654 or after)

My second answer is that Old Masters are essential to the continued flourishing of the arts. Although encouraging art students to look at Old Masters became unfashionable in the 1950s with artist-teachers such as Richard Hamilton – who advocated starting with a clean slate – the great majority of significant twentieth-century and contemporary artists have disregarded this. Picasso called it 'wrestling with painting', painting all the works missing from Malraux's Musée Imaginaire.

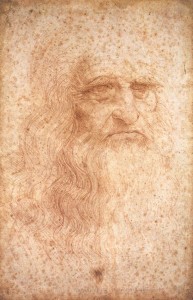

Old Masters such as Velázquez and El Greco were a source of constant inspiration for twentieth-century artists from Duchamp to Jackson Pollock and Francis Bacon. Picasso's seminal Les Demoiselles d'Avignon is in fact based on a subtle reworking of the monumental figures and broken lines in El Greco's The Vision of Saint John which he had just seen in the Parisian studio of his friend and fellow Spaniard Ignacio Zuloaga.

The Vision of Saint John

c.1608–1614, oil on canvas by El Greco (1541–1614)

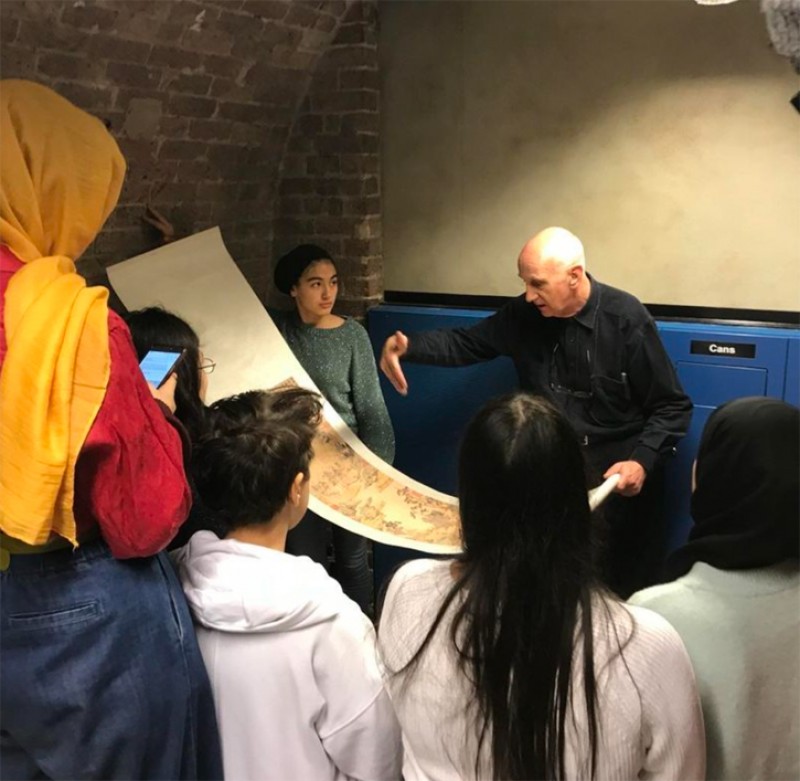

Contemporary artists look at Old Masters too. Sometimes this is in response to a residency such as Ron Mueck's at The National Gallery, but often it is less direct, the result of a lifetime of looking at all sorts of things. Anish Kapoor has spoken of his interest in Rembrandt and Soutine, Marlene Dumas of hers in Ingres, Jeremy Deller of Hogarth, just to name a few. Stormzy's recent album cover riffing on Leonardo's Last Supper reminds us that Old Master art even feeds popular culture including music, fashion, advertising and social media (think classical art memes!).

All this leads to my final answer. Year-on-year figures on visits to pre-twentieth-century collections around the UK aren't readily available, but we know that visits to London collections such as The National Gallery and National Portrait Gallery declined sharply in 2017. Even if The National Gallery may often seem packed, over 60% of visitors are tourists, and it's domestic visitors that are decreasing. Equally worrying was the 7% drop in visits by school children under 16, compared to the previous 12 months.

Cuts to museum funding in recent years indicate that museums will need to fight even to maintain current levels, and this will be difficult if it can be argued that Old Master paintings are of less and less interest to the nation.

We need to look to the future and think harder about how we encourage schools, art schools, and the general public to engage with and value these collections. We need act now to save them for future generations.

Nicola Jennings, Director of the Colnaghi Foundation

.jpg)