Diego Velázquez's mid-seventeenth-century scene of a mythological feast is sometimes plainly titled The Drinkers. The Museo del Prado in Madrid, the painting's proud home, calls it The Triumph of Bacchus.

The Triumph of Bacchus

c.1628–c.1629, oil on canvas by Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

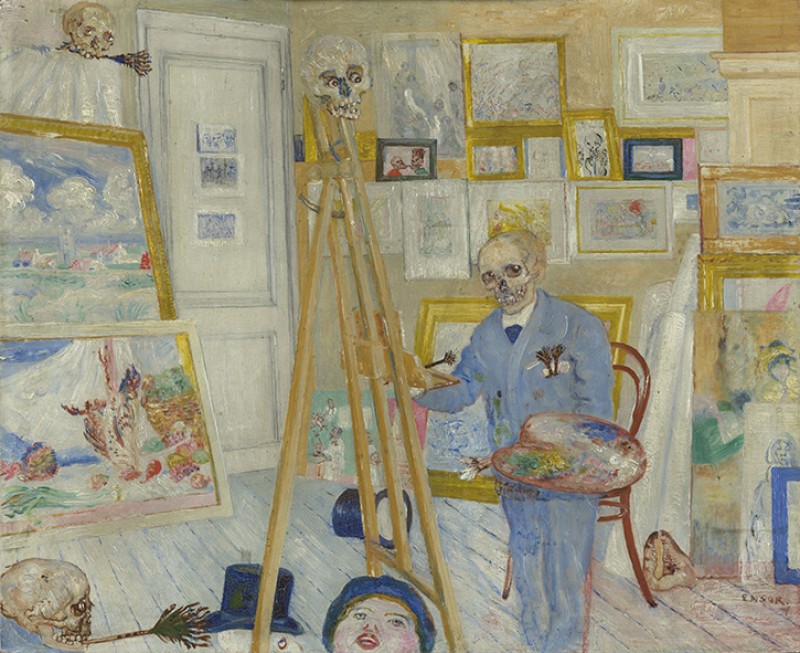

So what sort of triumph is this? It is the victory of the vine, the salvation provided by the intoxicating power of wine to liberate men from their troubles. The god Bacchus gave wine to humanity and an irrepressible cult of ecstasy and wild abandon – Ovid's Metamorphoses describes the god as the 'Father of revels and cries ecstatic'. Yet Bacchus is often seen as paradoxical, combining 'infinite vitality and savage destruction' (i), a fit characterisation of the demon drink.

A common Spanish title for Velázquez's picture, Los Borrachos, translates as The Drunkards. This brings it closer to the work of another Spaniard, Joaquín Sorolla (1863–1923) – The Drunkard, Zarauz – which was acquired by The National Gallery in 2020.

The Drunkard, Zarauz (El Borracho, Zarauz)

1910

Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (1863–1923)

Sorolla's picture came from a short stay in the Basque seaside town of Zarauz in 1910, where he produced a few rapidly painted pictures of hardened drinkers. These works are very different from Sorolla's typical output, which is easy on the eye, full of colour, and drenched in Spanish sunlight. Many of Sorolla's paintings hang in galleries across Europe and the USA, but the greatest number are to be found in the Museo Sorolla in Madrid.

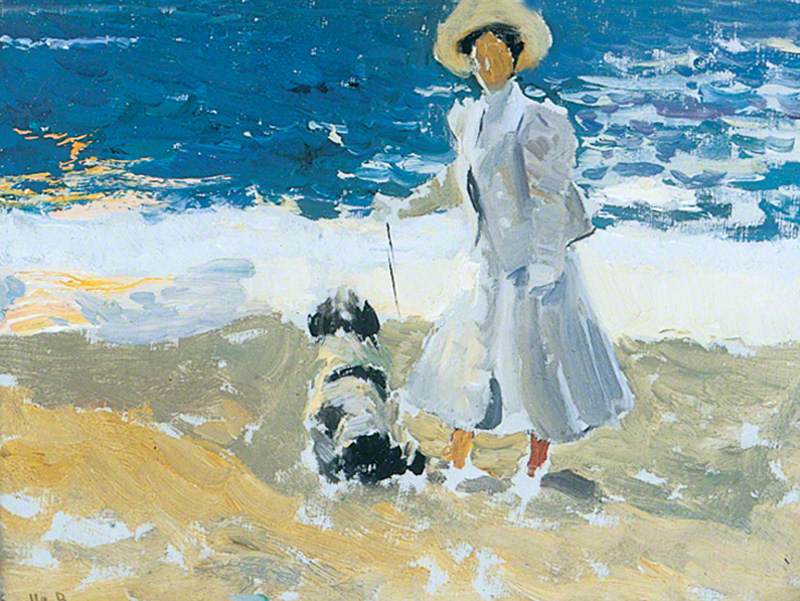

A Lady and a Dog on the Beach

1906

Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (1863–1923)

Elaine Kilmurray's review of the 2019 National Gallery show 'Sorolla: Spanish Master of Light' describes Sorolla's work as 'sensual, superabundant, hyper-visual painting – and a challenge to a generation that privileges the intellect in art'. This sums up Sorolla: largely disregarded by scholars, his paintings stand outside the intellectual progression of modernism. He belongs to a fashionable group of early twentieth-century artists, driven – it is claimed – by the market and labelled by Walter Sickert the 'Wriggle and Chiffon School'. In keeping with this verdict, another reviewer, Laura Cumming of The Guardian, saw little of value beneath the virtuosic performance, which she characterised as 'a kind of luxury painting, richly calorific, joyously upbeat and too often glib'.

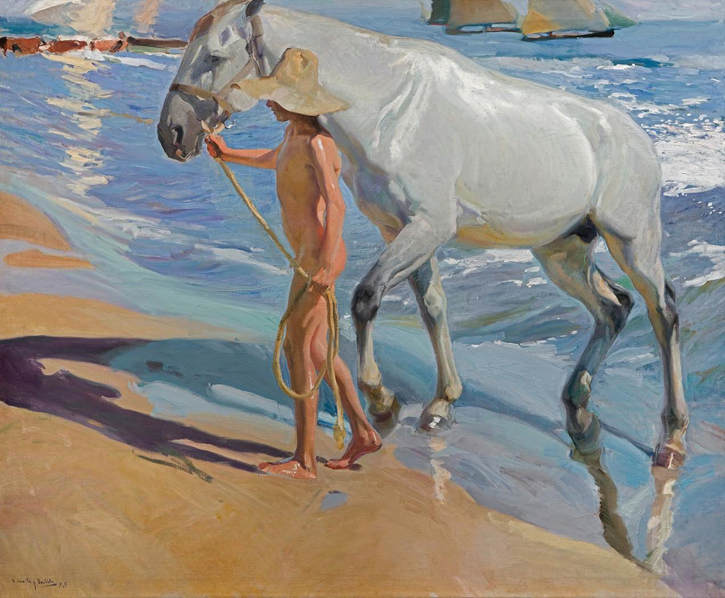

The Horse's Bath

1909, oil on canvas by Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (1863–1923)

Billed as 'the world's greatest living painter' at the only other London exhibition of his work, over a century earlier in 1908, Sorolla's status was questioned even in his lifetime. The accusation that his pictures are beautiful but lack a 'lesson to mankind', as reported in a 1911 article, certainly does not apply to certain of his socially minded works, powerfully exemplified by The Drunkard, Zarauz.

The Drunkard, Zarauz (El Borracho, Zarauz)

1910

Joaquín Sorolla y Bastida (1863–1923)

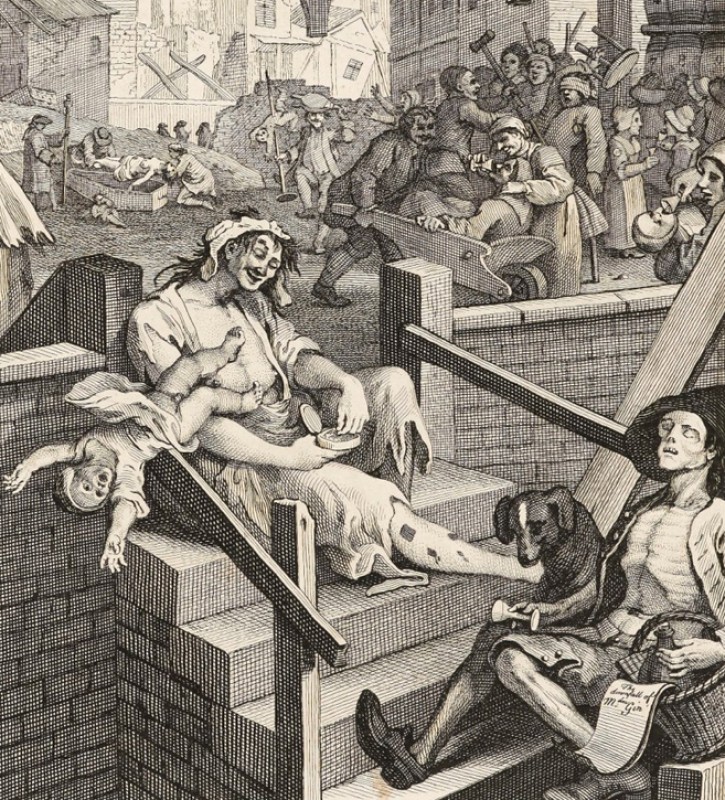

The murky interior is a scene of self-destruction and ugly coercion. The drunkest of the drinkers, known as Moscorra, looks up at us, struggling to focus. It is as if we have just walked in – strangers in town – in search of a free table. Around him are companions, urging him to further oblivion. Alcohol flushes their sunburnt faces, and the young red-haired man shoots us a look of suspicious contempt.

Comparing Sorolla's drinkers with those in Velázquez's work, we see two images of drunkenness by two virtuosic Spanish painters, 300 years apart: the formal similarities are striking, particularly if we invert one of the clustered groups of drinkers.

Detail of 'The Triumph of Bacchus', mirrored horizontally

c.1628–c.1629, oil on canvas by Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

In each picture, there's a drink under the nose of the chief toper, who fixes us with his gaze. His ruddy-faced companions are leaning in, one of whom gives us a knowing look. The marginal standing figures in each painting are similar dark forms, and while the angle and colour of the tavern table echo the broad, brown cloak of the silver-haired drinker in the Velázquez, Moscorra's trousered leg reminds us of the back of the drinker being crowned by Bacchus.

We cannot assume that Sorolla's composition imitates Bacchus, but he was a great admirer of the old master, and the Velázquez painting indisputably haunts this tavern scene. As a young artist, Sorolla paid homage by copying paintings by Velázquez, including studies of details from his works.

In Sorolla's tavern scene, a heavy-set companion thrusts a glass under Moscorra's nose. At first sight, we might easily confound this man's arm with Moscorra's own right arm. Was this visual confusion deliberate, we wonder? However it came about, the artist left it like that, so that the giver and the receiver become one, and we onlookers put a drink in Moscorra's hand, which in fact is not his.

And isn't the profile of the heavy-set man the same as the face we can just see intruding from the right? Are these twin good and bad angels with opposing messages about the allure of intoxication? Or is soused Moscorra – and aren't we – simply seeing double?

In Velázquez's painting, Bacchus looks away, with an expression that has attracted much speculation. It might indicate unease, nonchalance, distraction, disdain. Is he already searching for his next customers? All interpretations are possible. It appears that Velázquez did not want his god to consort too closely with these very human boozers – in artistic depictions of Bacchus, he is far more interested in proffering wine than in drinking it.

Detail of 'The Triumph of Bacchus'

c.1628–c.1629, oil on canvas by Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

Seated among these carousing peasants, Bacchus is a very different creature: the bright marmoreal flesh, uncoloured by sun or drink, the nakedness among dull brown capes and hats. His aloofness might provoke our suspicion. Here's the god who gave us wine, that relaxant, that anaesthetic to our troubles, and yet he cannot bring himself to look at the drinkers who live by it, who, we suspect, also suffer by it. There is hypocrisy in his averted gaze, and discomfort in being there – like a duchess giving to the poor who wants to get away as quickly as possible. As Jonathan Brown writes, it is as if he is 'looking for the cue that will terminate the encounter'.

Like Bacchus, Moscorra looks away from his drinking companions, but his watery gaze is pitiful, an appeal perhaps to us, to rescue him from this degradation. Or to stand him another drink?

Velázquez and Sorolla knew well that alcohol is far from a simple elixir. As with so much in life, what delights may quickly dismay – as Walter F. Otto explains in Dionysus: Myth and Cult:

'[T]he Greek of antiquity was caught up by the total seriousness of the truth that here pleasure and pain, enlightenment and destruction, the lovable and the horrible lived in close intimacy. It is this unity of the paradoxical which appeared in Dionysiac ecstasy with staggering force.'

In Velázquez's day, there was a belief that Bacchus had, in fact, not only visited Iberia but had ruled there. Whatever Velázquez made of this, one view is that Velázquez's Bacchus represents kingly largesse in his offer of wine, and that the painter chose Bacchus as his subject in order to please his royal patron Philip IV and thereby further his career at court (as put forward in Steven N. Orso's book on the painter). This would explain the well-behaved drinkers, whose obvious delight in receiving Bacchus's gift does not result in unseemly behaviour: the grinning drinker holds his bowl of wine with incredible steadiness, and the respectful bow of the peasant receiving the crown of ivy may indeed indicate earnest gratitude – and not sarcasm.

Although alcohol has been consumed in generous quantities in Spain for centuries, drunkenness that results in loss of self-control and, with it, one's dignity, is very much frowned upon. Contrast the debauchery seen in many works by northern European artists in Velázquez's time, where the effects of drink are frankly displayed. As John Hooper puts it in The New Spaniards (1995), '[m]ost Spaniards do not need alcohol to help them shed their inhibitions'.

Interior of a Tavern, Peasants Carousing

c.1635

Master of the Large Jars

Sorolla's tavern picture may seem out of keeping with the numerous sun-kissed seaside children, genteel family portraits and promenading ladies that were his more typical subject matter, but, in fact, he had responded earlier in his career to matters of social concern, in paintings whose subjects included prostitution, striking workers and the dangerous conditions endured by fishermen. Since the mid-nineteenth century, there was a concerted movement in Spain, as elsewhere, to tackle the problem of alcoholism among the poorer classes, although it is interesting to note that there was some disagreement about whether alcohol was the cause of misery or misery the cause of alcoholism (ii).

The Drunkard, Zarauz records with brutal truthfulness the nature of addiction, evoking through its colours and composition its great predecessor, The Triumph of Bacchus. In these pictures, the eye is drawn to the faces of Bacchus and Moscorra, each of which presents a deliberate ambiguity. Bacchus is a creature of mythic complexity, whose image is rich in possibilities. Moscorra's hazy, miasmic stare is both sad and defiant. His ruin is no triumph. He musters a weak grin, a faint bonhomie, with what is left of his dignity.

But we will pass by, take our drinks to a far table, and keep Bacchus in check – so we think, or hope.

Adam Wattam, writer

(i) Walter F. Otto, Dionysus: Myth and Cult, p.121

(ii) Ricardo Campos, 'Alcoholism and Medicine in Spain in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century', History of Psychiatry 9, no. 2, 1998, pp.201–215

Further reading

Jonathan Brown, Collected Writings on Velázquez, Yale University Press, 2008

Philip Hook, Art of the Extreme, Profile Books, 2021

National Gallery Company, Sorolla: Spanish Master of Light, Yale University Press, 2019

Steven N. Orso, Velázquez, Los Borrachos, and Painting at the Court of Philip IV, Cambridge University Press, 1993

Enjoyed this story? Get all the latest Art UK stories sent directly to your inbox when you sign up for our newsletter.

.jpg)