What do the blind see?

People often assume the answer to this question is 'nothing at all'. But there are actually many answers. For some, it's a hazy, indistinct version of the world; for others, it is flashing lights and moving dots. People who have had their eyes removed see a kind of white fog, and others perceive colours in radically different ways. Blindness is a spectrum, and just as the people affected by sight loss are diverse, so too are the ways in which your vision can alter.

But painters throughout history, from the Impressionists to modern abstract artists, have provided us with the tools to better understand the reality of living with sight loss. By looking at art, we can learn how blind and partially sighted people might see the world in a different – but equally valid – way.

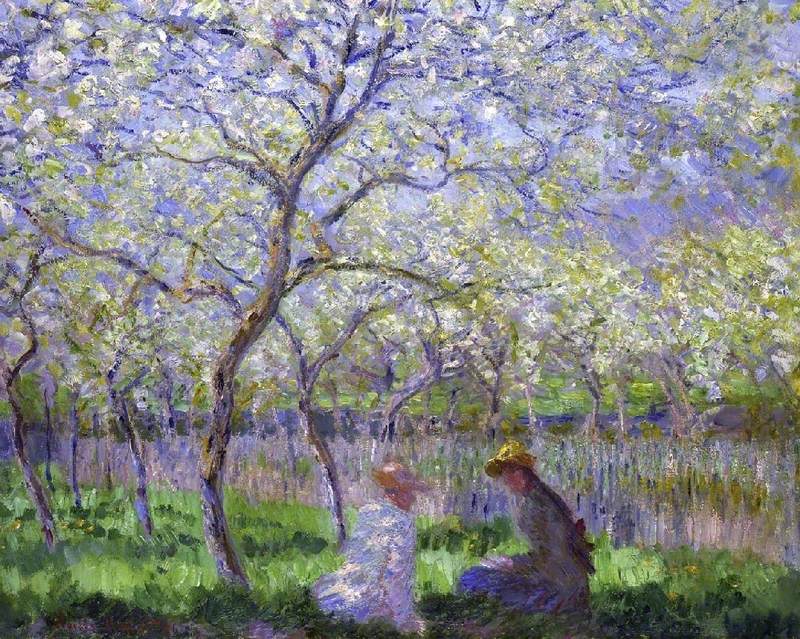

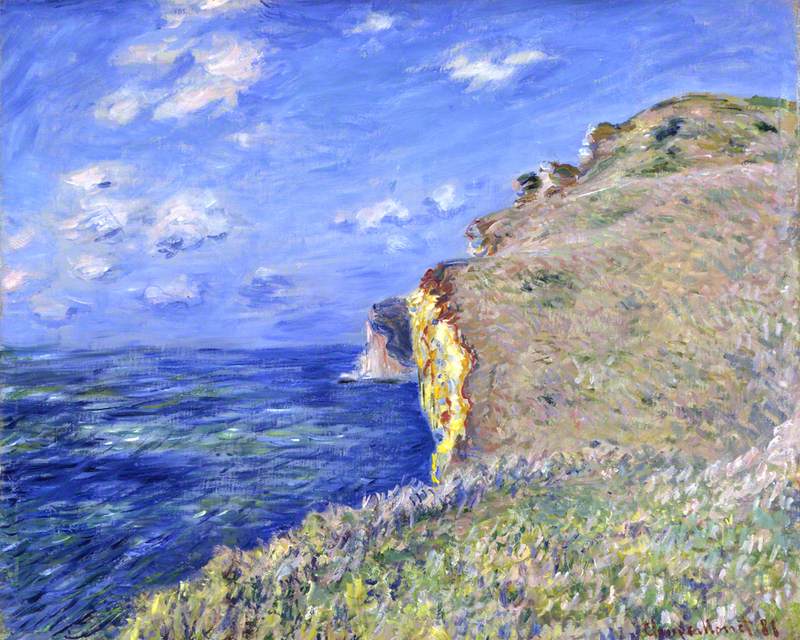

A good starting point is to consider perceptions of colour. For the Impressionists, the rules of colour were there to be broken. Claude Monet once said: 'Colour is my daylong obsession, joy, and torment.'

Their love affair with blue pigment led to the coinage of the term 'violettomania' or 'seeing blue', exemplified by Monet's Springtime and Waterlilies. The group drew much criticism for this vision of colour: one comment even denounced their works as looking like 'worm-eaten Roquefort cheese'.

But this innovative pigment usage serves as a window into the reality of colour blindness, a condition that affects three million people in the UK (about 4.5 per cent of the population). The Impressionists embraced the fact that colour is subjective, not objective, and through looking at their artworks we can better understand how people can have different relationships with the visible light spectrum.

The Impressionists also earned their name by using fast brushstrokes and broken-up colour to evoke their subjects, rather than accurately depict them with photorealistic clarity. In this way, they managed to capture what it's like to see using only peripheral vision: hazy, fugitive worlds, full of perceptible light, colour, and shapes, but lacking sharpness. For hundreds of thousands of people across the country who are severely visually impaired, this point of view does not exist only in art galleries, in framed masterpieces: it is an everyday reality.

Below is an interactive visualisation showing how a person with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy might see, compared to someone with 20/20 vision.

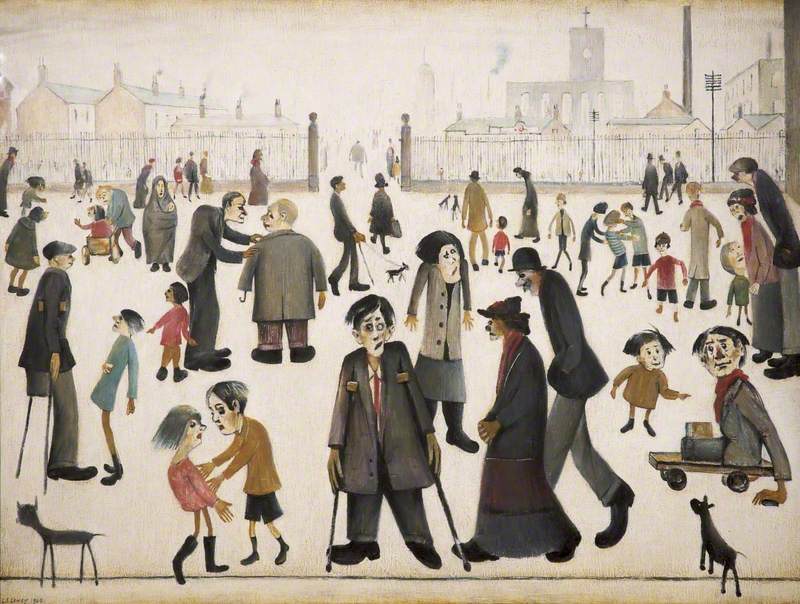

The leading cause of blindness in the UK is age-related macular degeneration (AMD), whereby those afflicted lose their central vision and must rely primarily on peripheral vision. The degeneration of the focal point is also symptomatic of various other eye conditions, including diabetes (the fifth most common cause of blindness) and diseases that affect the retina.

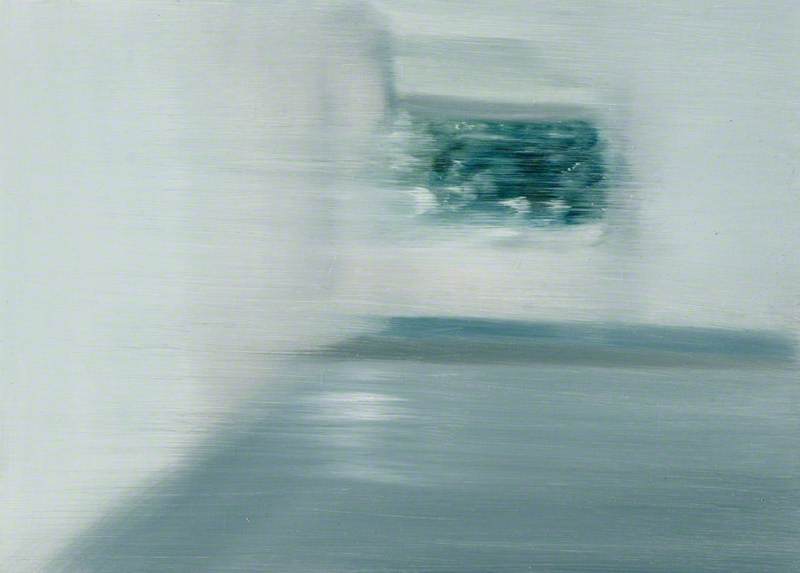

After the Impressionists, many other artists sacrificed clear, detailed depictions for evocative usage of light and colour, all of which act as windows into the world of central vision loss.

The oil paintings of Gordon Hales – who most enjoyed depicting 'ships and the sea, the Thames, men at work, the streets of London, the half-light' – also demonstrate this; so do Nicky Hodge's Mountain Series and Corridor Series.

The disorienting journey of the eye across these works as it searches for something in focus to anchor itself on is fruitless. So, too, is the search for definition in the periphery for those with central vision loss, and these paintings can help us understand what that feels like.

Abstract art also provides us with the tools to understand visual snow, whereby people see black or white dots moving around in their field of vision. A simple way to imagine this is by looking at paintings like White Abstract by Christopher Barke; for some blind and partially sighted people, shapes like this are constantly drifting across their eye-line, obstructing their view.

The following is an interactive visualisation showing what someone with acute retinal necrosis might see, compared to someone with 20/20 vision.

Visual snow persists even in darkness, and can create confusing nebulae of light and pattern, comparable to Laura Rayner's Abstract Galaxies (Purple, Blue and Black).

This interactive visualisation shows how a person with acute retinal necrosis might see, compared to someone with 20/20 vision.

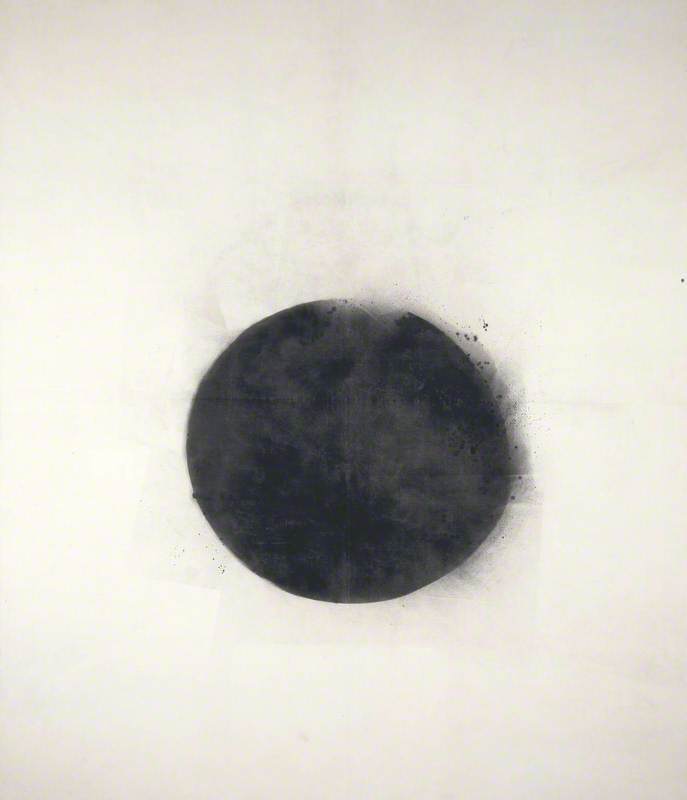

One further example of abstract art which teaches us about blindness is John Latham's Full Stop, completed during a three-month stay at the Chelsea Hotel in New York.

This painting was executed using a spray gun repeatedly, so that the one large dot is made of millions of smaller dots, and fragments slightly on one side, with a nebulous, stippled haze haloing it. This painting encapsulates what it is like to see big, oscillating shapes which obstruct the vision – shapes made up of tiny, shimmering dots, a phenomenon often caused by fluids leaking inside the eye.

This interactive visualisation shows how a person with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy might see, compared to someone with 20/20 vision.

Latham's chosen title, Full Stop, evokes endings – the end of a sentence, the end of language, and the end of art and culture. In this sense, it can be a poignant reminder that many forms of blindness do signify an end to a relationship with written text. But the work also evokes planetary beginnings, bodies materialising in deep space – a theme that is central to Latham's work. An end to a sentence and a relationship with one form of language can mean the beginning of a new one – so it is also apt that the circle shape recalls Braille, the tactile alphabet of dots used by more than 30,000 blind people in the UK.

The following is an interactive visualisation showing how a person with familial exudative vitreoretinopathy might see, compared to someone with 20/20 vision.

But it is the works of J. M. W. Turner that can teach us the most about blindness. Not only do his hazy, ephemeral landscapes – which became more incandescently vague in Turner's later years as he used oils increasingly transparently – help us understand central vision loss, but they are also a brilliant tool for understanding how the spectrum of blindness represents a change in subjectivity, rather than a complete stripping of ones ability to perceive beauty. For we are all experiencing blindness when we look at Turner's works today.

The artist famously worked with pigments that looked good when freshly applied, without any regard for posterity: cochineal carmine and chrome yellow, for example, faded even within Turner's lifetime. When William Winsor (one half of Winsor and Newton, still a manufacturer of fine art products) expressed concern over the longevity of Turner's chosen pigments, the artist responded: 'Your business, Winsor, is to make colour. Mine is to use them.' He also stored his canvases in extremely damp places without regard for the damage inflicted by these conditions.

As a result, the Turner works we see today look very different to how they did in his own time. Skies once vividly coloured with natural indigo are now grey or reddish in tone, due to the fact that Turner would mix this short-lived pigment with black or vermilion. Canvases once pristine are now marked by mould, discolouration, flaking, and all the preventable ravages of time and environment that Turner chose not to protect against.

And yet Turner is one of the UK's most beloved artists: The Fighting Temeraire was voted Britain's greatest painting in a 2005 public vote, beating out every other painting in a British collection, including Sunflowers by Vincent van Gogh. As of February 2020, Turner graces the polymer £20 note. Statues of the artist stand in the Victoria and Albert Museum, Royal Academy of Arts, and St Paul's Cathedral (in which crypt Turner is buried).

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

The Fighting Temeraire tugged to her Last Berth to be broken up, 1838 1839

Joseph Mallord William Turner (1775–1851)

The National Gallery, LondonTurner's works teach us that what is imperfect can still be beautiful and that all ways of seeing are valid. Even when blindness does mean a complete lack of vision, the link to beauty is far from severed. In fact, according to Picasso, 'painting is a blind man's profession': art is as much about emotional engagement as it is about objective appearances.

Throughout human history, art has expanded our understanding of ourselves, each other and the world around us. One of the ways it does that is by teaching us about the realities of sight loss. From art, we can become more informed and more tolerant people, and gain a wider appreciation of what others can see. The answer is never 'nothing at all'.

Maud Rowell, journalist