Tirzah Garwood (1908–1951) was a multi-talented artist and designer whose life was tragically cut short when she died of breast cancer aged only 42. While the fame of her first husband Eric Ravilious (1903–1942) has increased in recent years, especially since the 2015 Dulwich Picture Gallery blockbuster exhibition 'Ravilious', Garwood remains relatively unknown.

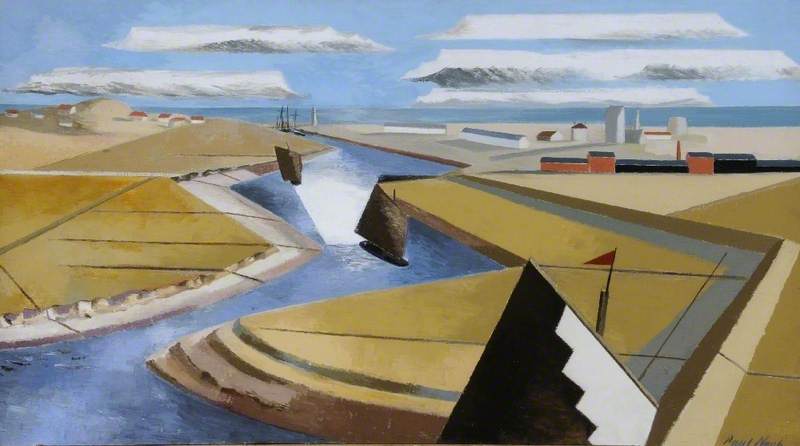

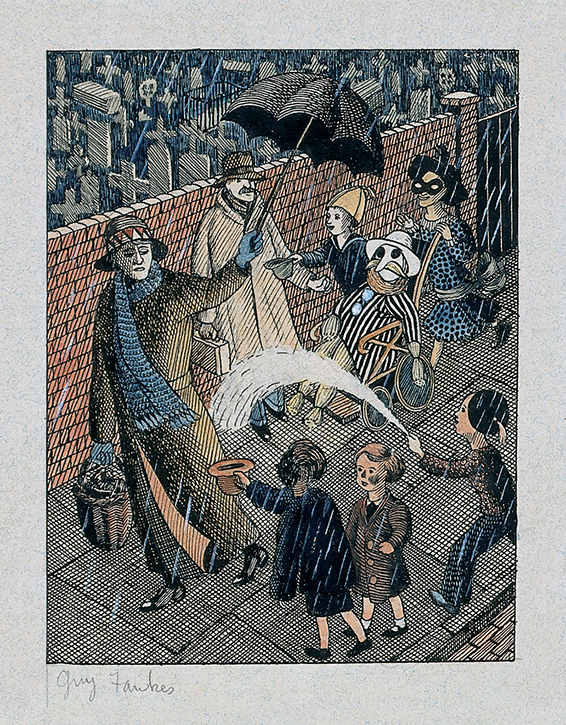

Guy Fawkes

c.1927, pen, ink & watercolour by Tirzah Garwood (1908–1951). Private collection

Her brilliance as a wood engraver and maker of marbled papers was acknowledged in her lifetime, but her early death meant that few were able to enjoy her captivating, collaged house 'portraits' and enigmatic oil paintings. Even so, her wide-ranging 1952 memorial exhibition was extended and transferred to London by public request. Now, more than 70 years later, Garwood is returning to the capital, as Dulwich Picture Gallery hosts the major survey exhibition 'Tirzah Garwood: Beyond Ravilious'.

The title and format of the show reflect the circumstances of the artist's life and career, and the importance of her personal and creative relationship with Ravilious. Eileen Lucy Garwood was born in Gillingham, Kent, in 1908, the middle child of five. An enquiry by a relative into 'Little Tertia' – the third child – led to her older siblings nicknaming her Tirzah after the Biblical character, and the name stuck. It suited the sharp-eyed, imaginative girl who spent summers hunting insects with her older brother John. Their father being a colonel in the Royal Artillery meant frequent house moves, particularly during the First World War, which the family spent mostly in the countryside south of Croydon. It was not until 1924 that they were finally united under one roof in Eastbourne.

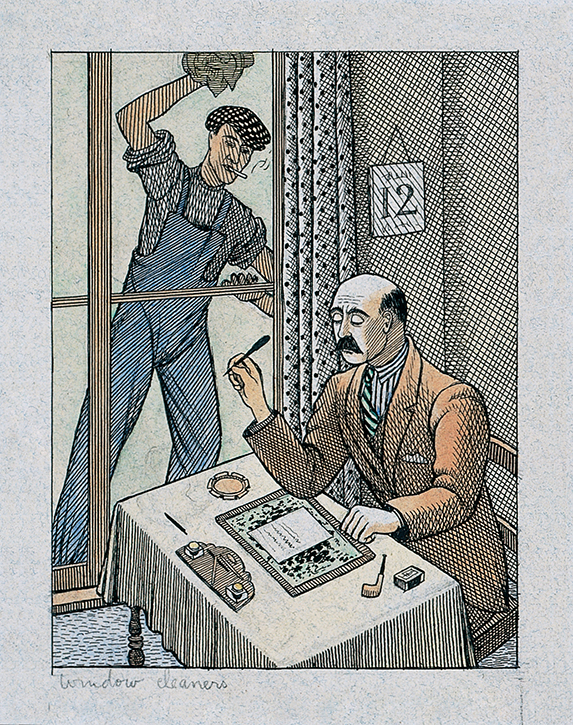

Window Cleaner

c.1927, pen, ink & watercolour by Tirzah Garwood (1908–1951). Private collection

Garwood's parents were both keen amateur artists and encouraged Tirzah to make botanical studies and draw scenes of fantasy and adventure. Having been head girl at West Hill School, she began studying at Eastbourne School of Art, attending full time from January 1926. When new teacher Ravilious encouraged his students to experiment with wood engraving, Garwood took to the unfamiliar medium with alacrity. She was still a teenager when the Society of Wood Engravers accepted her first work for exhibition the following year, and in 1928 she exhibited Hall of Mirrors.

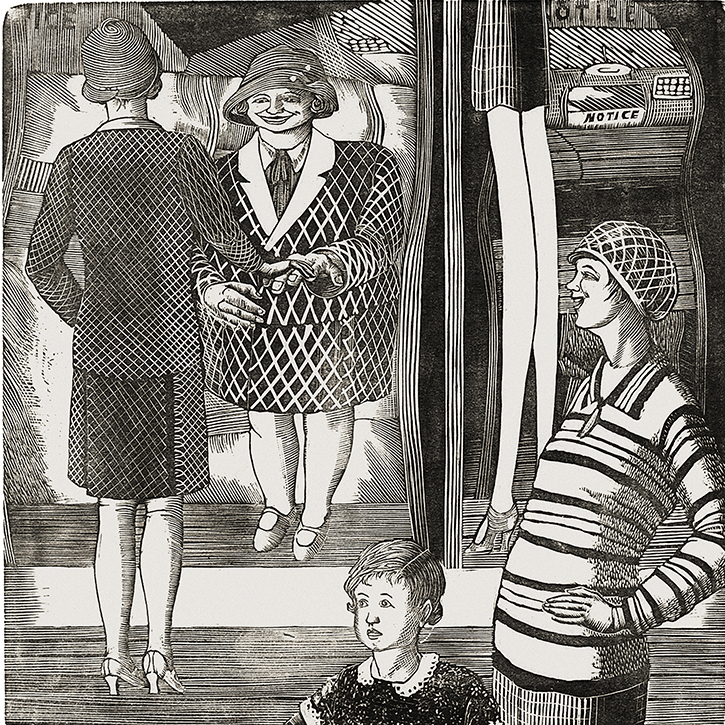

Hall of Mirrors

1928, wood engraving by Tirzah Garwood (1908–1951). Private collection

In this extraordinary self-portrait, we see Garwood happily admiring her oversized reflection which she (as the artist) brings to life by magnifying and distorting the criss-cross pattern on her skirt and jacket. She learned from Ravilious how to define textures and surfaces with contrasting patterns, but in some respects, she surpassed her teacher (who had, we should remember, been making wood engravings only a couple of years longer than her). The idea of presenting oneself as a reflection in a distorting mirror is brilliantly unconventional, and the execution is spot on. In the mirror to the right of hers, we see the elongated legs of the woman in the foreground, who is also chuckling heartily. The inclusion of the child sets up a triangle of contrasting characters in distinctive outfits. Garwood loved to depict different materials and styles of clothing in her wood engravings and was herself an excellent seamstress.

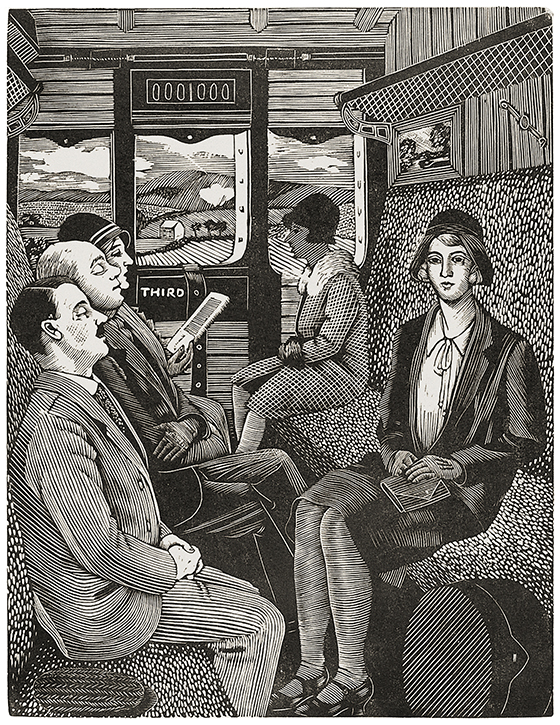

Train Journey

1929, wood engraving by Tirzah Garwood (1908–1951). Private collection

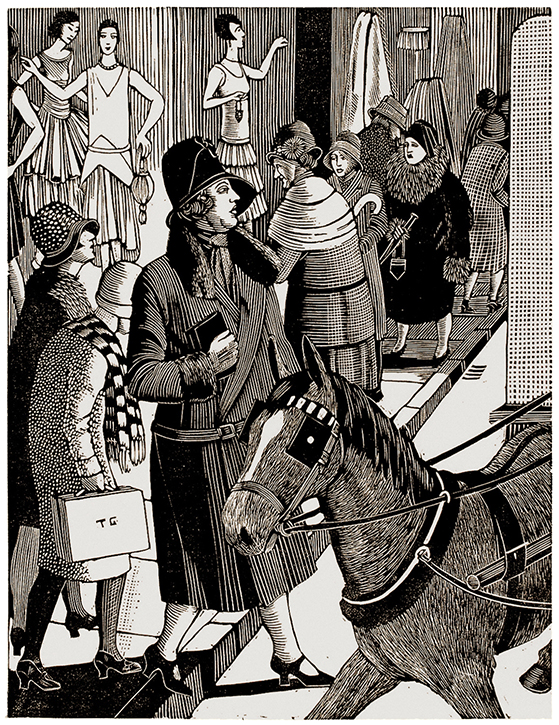

As a young woman in the 1920s, she adopted the pussy-bow blouses, loose-fitting v-neck sweaters and cloche hats of the day, but she still enjoyed poking fun at the absurdity of the fashion world. Indeed, a sometimes waspish humour suffuses many of the wood engravings she made between 1927 and 1930, particularly the series 'Relations'. In this group of prints, commissioned for a calendar which, sadly, was never published, Garwood turned her satirical gaze on her extended family – and on herself. In Kensington High Street she shows herself as a provincial visitor to bustling London (carrying a case initialled 'T. G.'), cowed (it seems) by the overbearing presence of her aunt or perhaps by the hubbub surrounding her stooped figure. Beyond the trotting horse, the women passing by are bundled up in coats and scarves, in contrast to the slender mannequins displaying summery fashions in the shop window nearby.

Kensington High Street

1929, wood engraving by Tirzah Garwood (1908–1951). Private collection

Each element of the scene is perfectly observed and realised, from the ridiculous postures of the mannequins to the range of hats worn by the passersby, who seem as oblivious to the shop window display as the blinkered horse is to the whole scene.

In 1930, Garwood married Eric Ravilious, and the pair set up home together, first in a flat on the Hammersmith/Chiswick border, then in rural Essex. Their first son, John, was born in 1935, followed by James in 1939 and Anne two years later. Artistically, this period was in some ways frustrating for Garwood, who devoted herself to her family. She made clothes and patchwork quilts and, most importantly, achieved renown as a maker of marbled papers. A stream of orders from design shops and private clients provided valuable income for the family, but this dried up with the outbreak of war. Then, in 1942, she suffered two life-changing blows. Early in the year she was diagnosed with breast cancer and underwent an emergency mastectomy. She was still recuperating when, in September, Ravilious was killed while on active service in Iceland.

Portrait of Peggy Angus

1949, oil on canvas by Tirzah Garwood (1908–1951). Private collection

Garwood recorded in her autobiography – Long Live Great Bardfield, which she was writing at the time – that she suffered 'spasms of dreadful sorrow ' after her husband's death, but following a period of mourning, she rallied. In June 1944, she went to visit her friend, fellow artist Peggy Angus, at Furlongs, her cottage near Lewes. As gliders flew overhead transporting troops to join the invasion of France, Garwood studied the local scene and, later that summer, painted Etna, which is based on the view north from Furlongs to Mount Caburn.

'I have started painting in oil,' she wrote to Angus, 'and I believe it may be my cup of tea.'

Etna

1944, oil on canvas by Tirzah Garwood (1908–1951). Private collection

As with wood engraving, she took to this new medium quickly. In Etna, the hill itself is painted with authority, the solid mass conveyed with subtle variations in tone. Garwood's first experiment with oils involved copying a naive nineteenth-century painting of a cockerel, and she brought this direct, clear approach to Etna. The farmhouse and cyclist are perfect miniatures. Even the hens' feathers are painted in meticulous detail. Placing the viewer low down among the barley and wildflowers, she creates the impression that the crops are towering over the chickens, which are the same size as the driver of... a toy train. This is Etna, a tin toy bought from a jumble sale and perhaps included here to amuse the children. The effect is magical, turning the scene – one familiar to travellers between Lewes and Eastbourne – into a surreal dream.

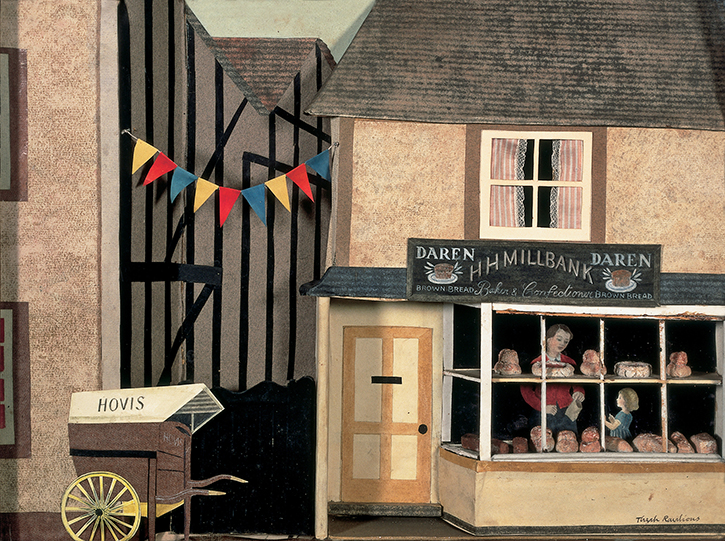

A friend wrote of Garwood at the time that she painted in the kitchen with the children locked out, but Anne still managed 'to press her nose against one picture'. It was perhaps for this reason the artist shifted her attention to collage, creating in 1945 the first of a series of 'portraits' of houses and other buildings that appealed to her. This proved a timely venture, as two years later the first 'Pictures for Schools' exhibition was held at the Victoria and Albert Museum by the new Society for Education through Art. A thousand works were submitted by artists, out of which 250 were displayed for sale to education authorities – and for the pleasure of young visitors. Garwood submitted Daren, Baker's Shop, which was voted best in show by the youthful audience.

Daren, Baker's Shop

1945–1946, paper & card collage, wood & Pyruma set in box frame by Tirzah Garwood (1908–1951). Private collection

One can see why the work would appeal to children, having as it does the 'world-in-miniature' quality of the doll's house. Here is a baker's shop in Wethersfield, Essex, modelled from collaged paper and set in a deeply recessed frame of the kind used by butterfly collectors to display their wares. This allows Garwood to offer a view through the window (a frame within a frame), where we see Anne Ravilious choosing a bun, both child and foodstuff made from a modelling clay called Pyruma. What makes the collaged models so alluring, however, is their meticulous artistry. The bunting with its nine pennants is perfectly positioned, while the pattern on the wall beyond resembles an abstract painting. Garwood shared with her late husband a passion for intriguing wheeled vehicles, indulged here in the form of the baker's barrow.

Indeed, Garwood shared numerous interests with Ravilious, and one of the chief reasons for including a small number of his works in this exhibition at Dulwich is to explore the similarities and differences in their approaches to various motifs. So, the work of both artists can be seen in the first two rooms, but after the mausoleum, it is all Garwood: a change reflecting her artistic reawakening in 1944. For a few short years after this, life was good. A year after the war ended, Garwood married BBC producer Henry Swanzy, and the family moved to leafy Primrose Hill. Garwood made collages and marbled papers, and recorded trips to Ireland and the Hebrides in oil paintings.

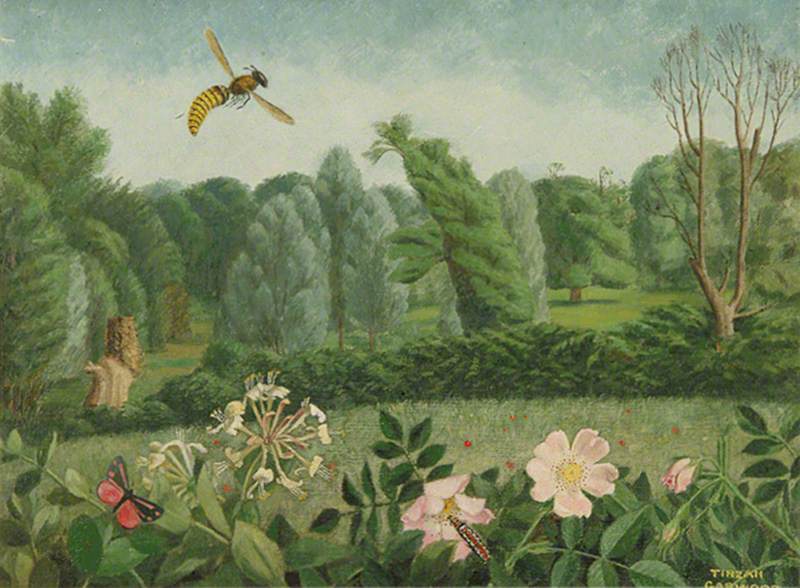

Springtime of Flight

1950, oil on canvas by Tirzah Garwood (1908–1951). Private collection

This honeymoon period ended with the return of her cancer in 1948, and this time there was to be no respite. By the spring of 1950, the cancer had spread, and that summer she moved to Copford Place, a nursing home in rural Essex, where she died in March 1951. Throughout her last year, Garwood astonished her friends with her gaiety and enthusiasm for life. Free to paint as much as her illness allowed, she did so, producing around 20 canvases. They are small, reflecting the fact that she was often confined to bed, and, like so much of her work, painted in a direct, seemingly straightforward style that belies hidden complexities. Often, she addressed her terrible plight but did so obliquely and even playfully.

Weewak's Kitten

oil on canvas by Tirzah Garwood (1908–1951). Private collection

The painting Weewak's Kitten appears, on the face of it, to depict a whimsical castle built in a garden by Anne. They were visiting Garwood's friends, the artists John and Christine Nash, and it was the latter's beautiful German bricks Anne used; their cat Weewak was named after an island in Papua New Guinea. So, the house of bricks stands among the mare's tail and euphorbia. Just to the right, in the shadows, the black kitten sits. It is larger than life in this miniature garden world, and its expression is not friendly but coldly curious. The eyes are set close together and they gaze unblinkingly at the castle. An attack is coming, but is the sense of imminent threat just that of a child who knows her wonderful castle is about to be knocked down by a naughty kitten? Or does the cat symbolise death, waiting without emotion in the wings? With the black pansies in the foreground, the enigmatic structure could be seen as a mausoleum – but at the same time, it remains the child's castle in the garden.

Spanish Lady

1950, oil on canvas by Tirzah Garwood (1908–1951). Private collection

Only occasionally in this last year did Garwood come close to despair, but when she did, she produced a work of haunting beauty. Her Spanish Lady is modelled on a Victorian water bottle, with a head that lifted off and acted as a stopper. Made of unglazed clay, this ornament stood on the mantelpiece at Adelaide Road in Primrose Hill. In April 1950, depressed as she rarely was by a new and terrible diagnosis and by the side effects of the treatment that followed, Garwood painted this familiar figure in an imagined night garden, surrounded by ghostly spring flowers and with a pale owl at her shoulder. That she meant this as a kind of self-portrait seems clear, especially given the resemblance between the long-necked jug and her own physique. Likewise, the pale solemnity of the painting and its nocturnal setting suggest that she was contemplating her own mortality. This is the final work in the exhibition, and a suitable memorial to an artist of unique, unforgettable vision.

James Russell, author, art historian and curator

'Tirzah Garwood: Beyond Ravilious' runs from 19th November 2024 to 26th May 2025. A digital exhibition guide is available on the Bloomberg Connects app

This article was originally published in In View, Dulwich Picture Gallery's members' magazine