'BRINK: Caroline Lucas curates the Towner Collection' was on display from 14th December 2019 to 6th Setember 2020, but was closed temporarily in the middle of the run due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We invited Towner Eastbourne's Head of Collections & Exhibitions, Sara Cooper, to interview the curator of the show, Caroline Lucas MP.

A politician, environmental campaigner and cultural advocate, this is Caroline's first curated exhibition. Reflecting her interests in environmentalism and work for the UK's Green Party, the exhibition comprises of artworks from the Towner Collection that contemplate the changing effects on our landscape.

Continue scrolling to read the full interview.

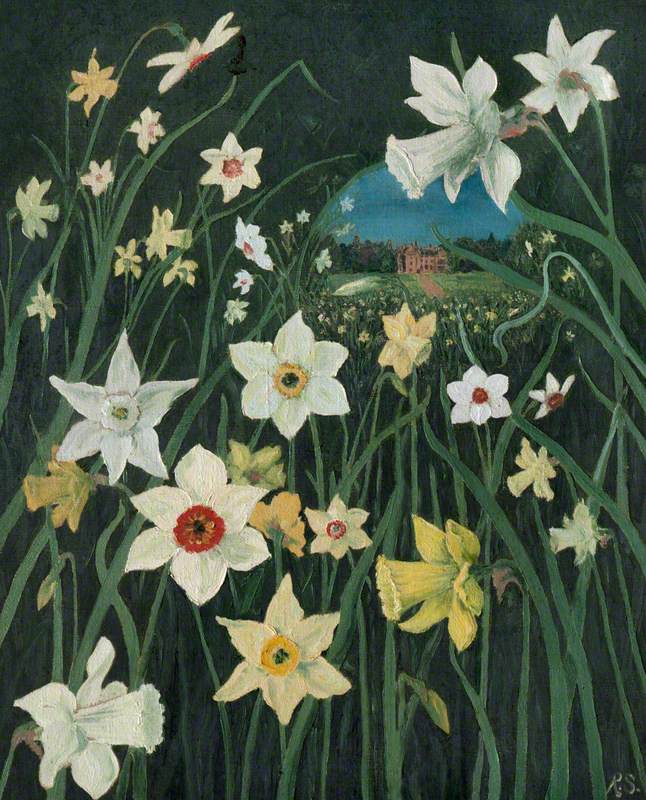

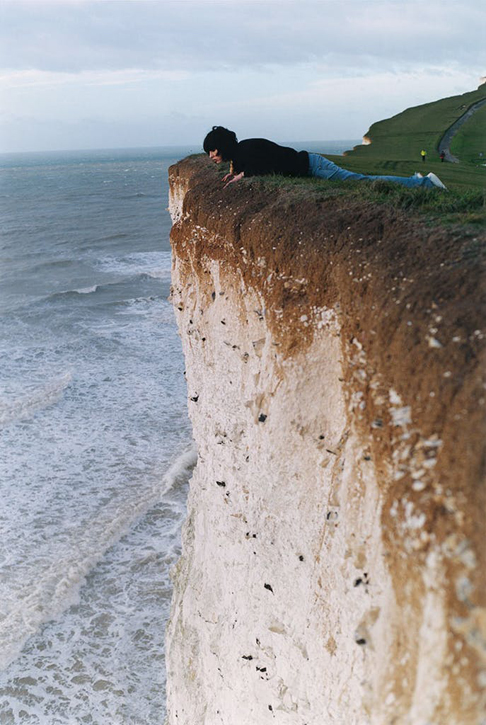

End of Land I

2002, chromogenic print by Wolfgang Tillmans (b.1968)

Sara Cooper, Towner Eastbourne: Caroline, thank you for taking the time to talk to me and answer some further questions about the BRINK exhibition. It feels like so much has happened since we opened the exhibition! Our audience were able to see it for a time before we had to suddenly close the show and Towner Eastbourne due to COVID-19. Whilst we haven't been able to physically see the works in the show I feel like this period has given us an opportunity to reflect further on some of the issues you raised through your selection of works, and has, in fact, shifted some of those issues into an even more pressing and pertinent place. But before we talk about those factors, I wonder if you could just tell the readers a bit about the show and its content in a nutshell?

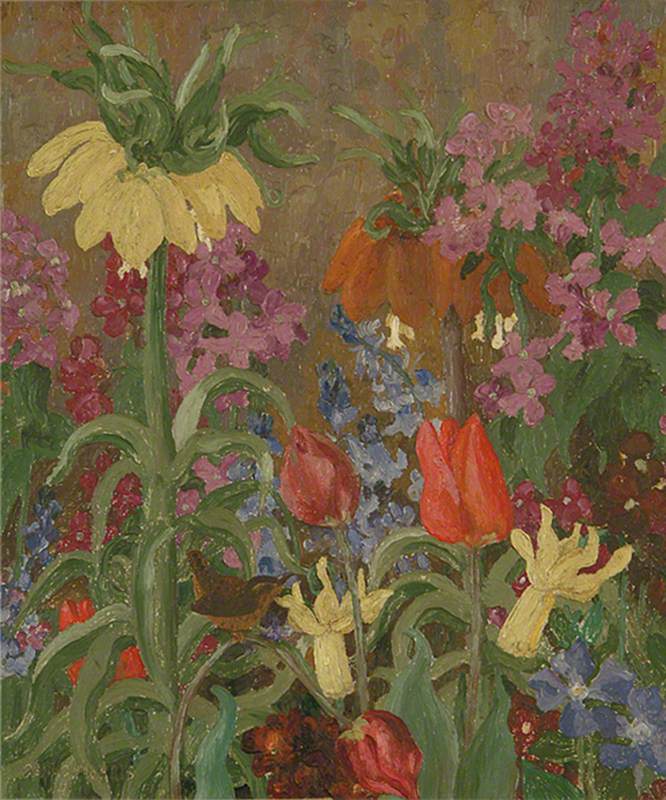

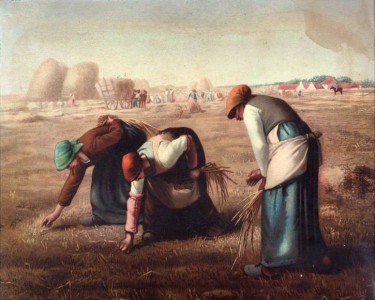

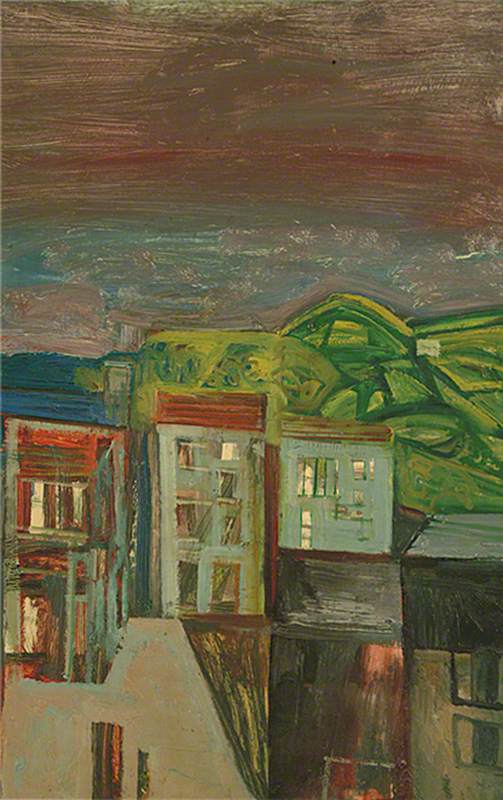

Caroline Lucas, Curator of BRINK: BRINK is about love for nature and the natural world around us – and about the threat they're under from the impacts of the climate emergency and growing environmental destruction. One of the lovely things about the Towner Collection is that there are so many landscapes and seascapes, a lot of them local to the gallery in Sussex, and I was hoping people might look at them differently when set within the overall context of a world on the brink: a world where accelerating climate change could change everything.

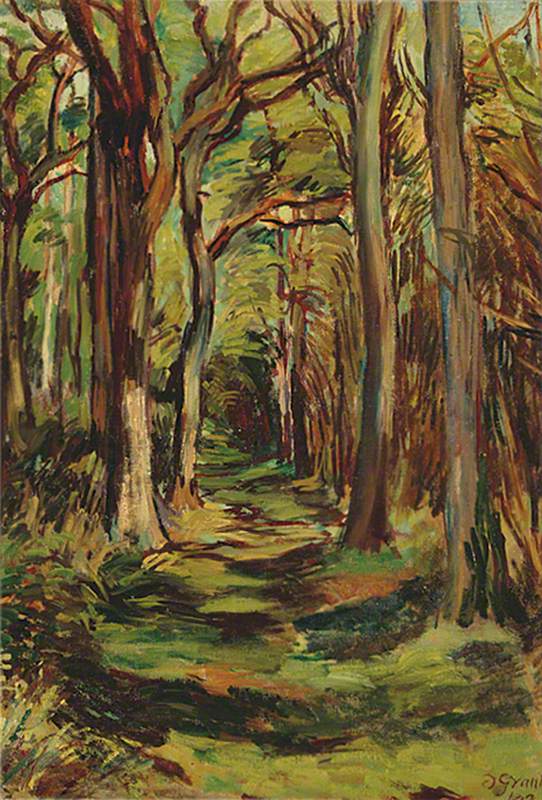

One of my favourite parts of the exhibition is the 'wall of trees' – a selection of paintings, prints, photographs and drawings, from Eric Ravilious to Mircea Cantor via Duncan Grant and others, representing the place trees have in our hearts. As well as sustaining us emotionally, we're also learning a lot more about how vital trees are on a physical level in terms of sequestering the carbon and cleaning the air. Even more exciting, and what Jennifer Dickson's etchings, Night Trees and Tree Structure, put me in mind of, is the emerging science about how trees 'communicate' with one another via underground fungal networks, allowing them to distribute sugars and nitrogen and phosphorus between them. What we're looking at in a forest is not single trees, but a forest community, connected by literally miles of super-fine threads called hyphae that fungi send out through the soil.

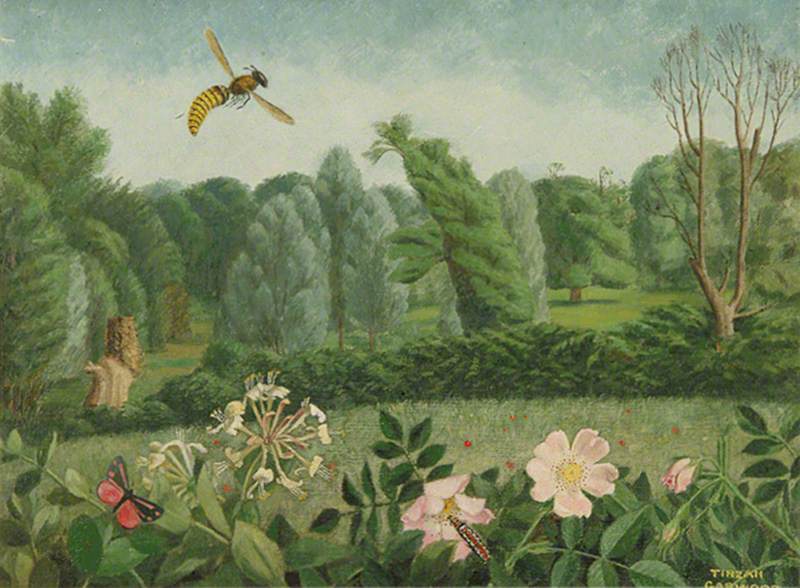

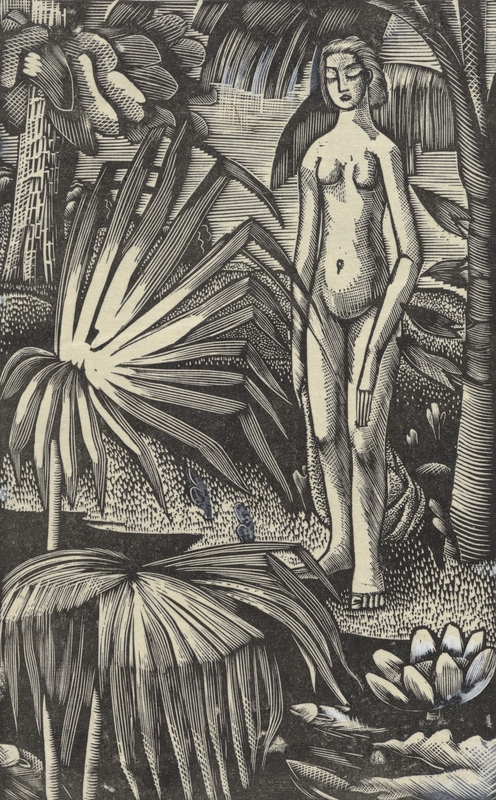

I was also keen to feature some of the works of Tirzah Garwood, who should be better known for her own work, rather than only for being the wife of Eric Ravilious. Hornet with Wild Roses and Orchid Hunters in Brazil, both so vibrant and full of rich colour, remind me of the insect world we're losing. In my lifetime alone, we've wiped out half of the wildlife in this country. Bird song has thinned, the buzz around the flowers is quieter and there is less colour in the fields. It worries me that unless we pay attention, unless we celebrate what we have, we won't appreciate what we are losing and won't preserve it.

Sara: The idea of inviting external people to select the Collection displays was a new strategy for Towner and as the first person I invited, I was delighted when you accepted the challenge. Can you say something about your initial response to the invitation?

Caroline: I remember getting your email and genuinely feeling that I couldn't believe my luck! It was an amazing opportunity to become immersed in over 5,000 artworks and having the privilege of being able to choose from among them. But as well as feeling incredibly honoured and excited, I have to admit that I also felt pretty overwhelmed. Where on earth would I start? And did it matter that I didn't know very much about the Collection? It was really helpful when you explained that the idea behind having a programme of guest curators was to have someone coming in from the outside who might be able to bring a fresh set of interests to the Collection and make new connections.

Sara: Once the discussions began and then you came to Towner to look at the Collection what did you most enjoy about curating the show? And what were some of the more challenging aspects? From my perspective I really enjoyed hearing your take on some of the works, hearing about what you liked and why, and how aspects of the Collection spoke to you and your interests. As a curator, we are sometimes guilty of slipping in to working with 'favourites' or getting bound into a certain aesthetic, so for myself, and for our Exhibitions Curator Karen Taylor, it was quite liberating to have fresh eyes and new perspectives on the Collection.

Installation shot including Joe Hill, Sara Cooper and Caroline Lucas

Sara: It was so rewarding being able to use the Collection works as a conduit for discussions about the environment, climate change, the declaration of a climate emergency and our shared concerns and fears about these issues, but also our optimism that there is a new generation of people prepared to stand up and make changes to fight some of these issues.

Caroline: One of the things I most enjoyed was simply the time to explore new works and make new discoveries – for example, the exquisite detail of the beautiful but tiny Robert Morris ink drawings of the cliffs and the Downs, the sea views of Victor Pasmore and David Jones or Nick Johnson's painting of his characterful lurcher, which I immediately fell in love with. But it was also really exciting to think more about the role art can play in bringing about change, reminding us that human beings are endlessly creative, and that when we choose to, we can make things happen. The more challenging aspects were definitely trying to work out what to leave out!

Sara: At a moment when Eastbourne Borough Council had recognised and declared a Climate Emergency and began taking steps to implement changes, Towner was able to be part of that conversation and was able to do what I believe we can do best, which is using art as a way of communicating ideas, concerns and fears, but also to foster an understanding, appreciation and a passion for an issue amongst our community and audiences. So that's why I found working on BRINK so rewarding: what was it that you found special and interesting about our Collection during the process and why?

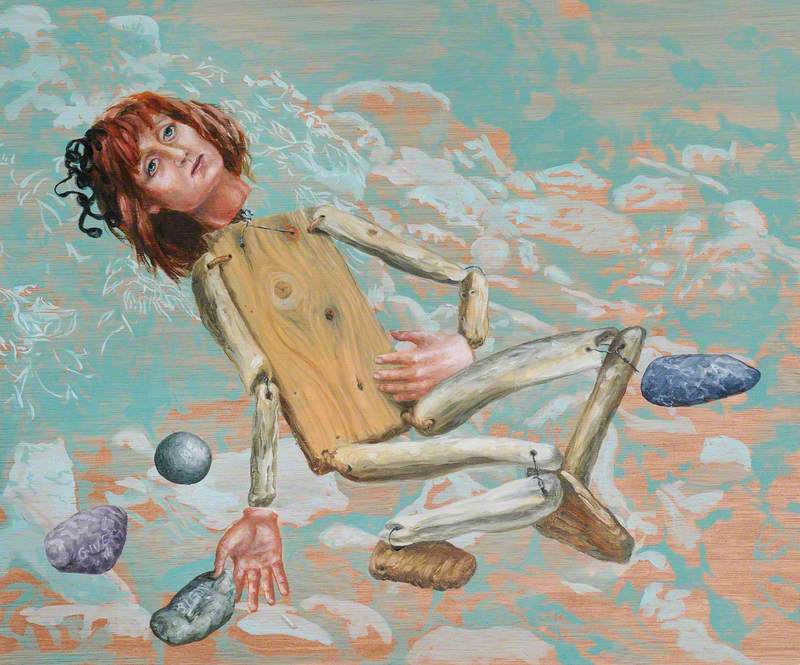

Caroline: As a Green politician, I spend a lot of time trying to work out how to make change happen at the scale and speed the science demands. And maybe one of the many reasons why we have not made the changes that are needed is because people haven't made an emotional connection with what we stand to lose if the climate breaks down. You can see why, because who wants to immerse themselves in that horror, really?

Yet we need some way of being able to do that safely, and constructively. So paradoxically perhaps at the time when the case for urgent action becomes most apparent, being able to address some of these issues through art, albeit obliquely, feels apt. I spend my life banging on about the fact that we have only ten years left to halve global climate emissions. We know what we need to do, yet still the political will is lacking. And that's what makes me feel, in a sense, that art is more important than ever – because it can reach people who perhaps wouldn't otherwise engage with these issues, and has the potential to generate change.

Sara: In order to continue the important conversations that began through BRINK we set up a 'provocation wall' in the gallery, providing visitors with an opportunity to have their say on the issues and any changes they feel can be made either by themselves as individuals or that we should make collectively as a society. From all these comments cards, of which there were hundreds, our aim is to produce a BRINK Manifesto that we will share widely with the public and with our councillors and politicians.

Sara: Can you talk about your (ambitions) or hopes for the manifesto?

Caroline: If part of the aim of the exhibition is to challenge people to ask different questions about familiar landscapes, and if part of the role of art is to stimulate conversations that might otherwise not happen, then it has to be a two-way process, there needs to be an interaction. So the provocation wall, and the manifesto it gave rise to, were partly about celebrating the fact that young people, in particular, are such a source of hope but also about encouraging people to think about what they themselves can do: there's no point raising questions about the destruction of the environment without giving people some sense of agency. I'm hoping we can present the manifesto to policymakers, both locally and nationally, at the end of the exhibition to demonstrate the public appetite for change, but it needs to be a living document too – one that people can revisit and revise.

Sara: Perhaps a pertinent place to finish would be to talk about BRINK in the context of the times in which we are currently living. COVID-19 and the lockdown have raised so many issues and debates about society and its inequalities, but in this context, focusing on the environment and landscape: I have certainly been part of numerous discussions about the impact of lockdown on our relationship to the environment – whether that's about the drop in air pollution and improved air quality, fewer cars on the roads and planes in the sky, species recovery, etc. There are many very positive conversations about what happens next, which I'm hoping that the BRINK manifesto can be part of.

Sara: Can BRINK take on new meaning, in the days we are living through?

Caroline: In A Paradise Built in Hell, the US writer Rebecca Solnit writes that disasters can give us a glimpse of who else we ourselves may be, and what else our society could become. The COVID-19 pandemic has been an unprecedented disaster, but it has also forced many of us to re-evaluate what matters in our lives, and to think about how we might live differently. It has reminded us about the importance of community, but also about the benefits of cleaner air, clearer birdsong, and quieter streets, as well as shining a spotlight on the inequality that scars our country, revealing how race and class are such important determinants in terms of its impacts.

Political failure is, at root, a failure of imagination. Yet the strange events of the past few months have forced us to imagine things differently. For decades those of us campaigning for a fairer, greener world have been told to be realistic, that we can't be too ambitious, that many things just aren't possible. Yet it turns out that when the political will is there, enormously bold change can happen. We've seen how governments can cancel NHS debt overnight, renationalise whole industries, provide homes for the homeless, and pay the salaries of more than 6 million people. That means that, as we emerge from the peak of the pandemic, they can also choose to build back better. Going 'back to normal' is nowhere near good enough because normal was failing the vast majority of people as well as trashing the planet.

So at this moment of re-evaluation, perhaps the arts in general, including BRINK, can offer a source of inspiration, restoration and connection – as well as a spur to action. We need to rebuild a world that is fairer – and one that is greener too. Because there is such urgency to this. As US climate campaigner Bill McKibben says, when it comes to the environment, winning slowly is the same as losing. The biggest threat is not the climate deniers but the climate delayers. Net-zero by 2050 is just too late – Greta Thunberg says we're living in a house that's on fire – she's right – but when you dial 999 and ask for a fire engine, you don't ask it to come in 30 years' time – you ask for it right now.

Sara: Thank you so much for your time, Caroline.

Caroline: Thank you, Sara.

Sara Cooper, Head of Collections & Exhibitions, Towner Eastbourne

BRINK: Caroline Lucas curates the Towner Collection was on display from 14th December 2019 to 6th September 2020, with a temporary closure in 2020 due to COVID-19