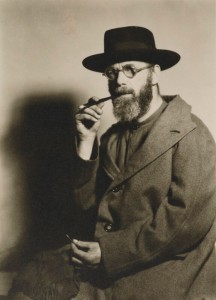

Given the futuristic look of the genre known as Op Art, it is fitting that the artist widely regarded as the founder of the movement is one of the few to have seen his works travel to space. In 1982, the pioneering French astronaut Jean-Loup Chrétien took part in a mission to the Soviet space station, Salyut 7, accompanied by prints of works by Victor Vasarely. This was a fitting tribute to an artist who did much to define Op Art, with his experiments in the optical illusions that gave the movement its name.

These pioneering innovations occurred during the late 1950s and 1960s, by which time the Hungarian-born, France-based Vasarely had already made his name as a painter. His fascination with illusory effects developed from his grounding in abstract art, a genre in which he had become known for vibrant compositions involving geometric but also fluid forms.

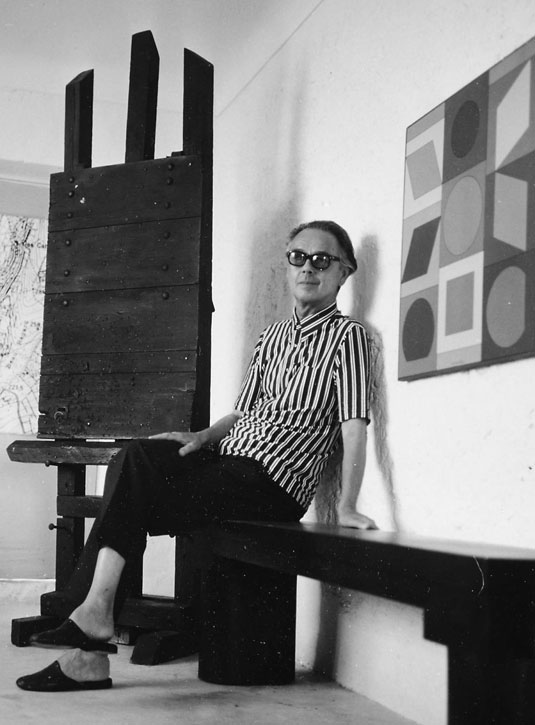

Victor Vasarely

Born and raised in Pécs, in southern Hungary, Vasarely demonstrated an early interest in science as well as art – an interest that would continue to shape his career. Although talented in drawing, he originally enrolled at the University of Budapest in 1925 to study medicine, dropping out two years later to pursue art. Later, he joined the private Műhely School, known as the 'Bauhaus of Budapest', where he studied graphic design. In 1930, he moved to Paris, eventually finding work in advertising to support his family, and his reputation grew as a respected designer. The artist explained later how working in advertising influenced his sense of the role of an artist: 'The extreme variety of its form leads the advertising designer to mute his personality.' Advertising also taught him about psychology – how we absorb images and process visual information.

In 1944, Vasarely had his first solo exhibition at the avant-garde Denise René Gallery in Paris. During the summer of 1948, he was invited to stay in the Provençal hill town of Gordes, which had a vital influence on his work for the next several years. So much so, that this period of his oeuvre became known as 'Gordes-Crystal'. While making drawings from the window of his lodgings, he found his sense of perspective muddled. Under the intense Mediterranean sun, shadows and walls became confused, solids and voids merged.

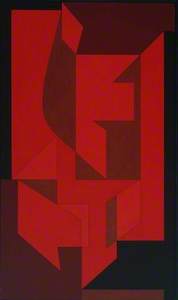

He later wrote: 'Thus identifiable things are transmuted into abstractions and begin their own independent life.' This realisation led him to work with flat planes that brought together figures and the ground under them as shifting forms. Although only completed almost a decade later, the oil painting Nives II (1949–1958) was first conceived in Gordes and later completed in Paris. Part of a series of similarly named works, its title, the name of a small town Belgian town, comes from Vasarely's practice of giving abstract works on completion geographical placenames.

The artist was not only limited to drawing and painting. As seen in Composition 'Pamir' (1949–1953), referring to the mountain range Pamir in central Asia, the artist stuck painted geometric sections of paper to the canvas. Whatever the format, though, Vasarely limited himself to a restricted number of forms and colours.

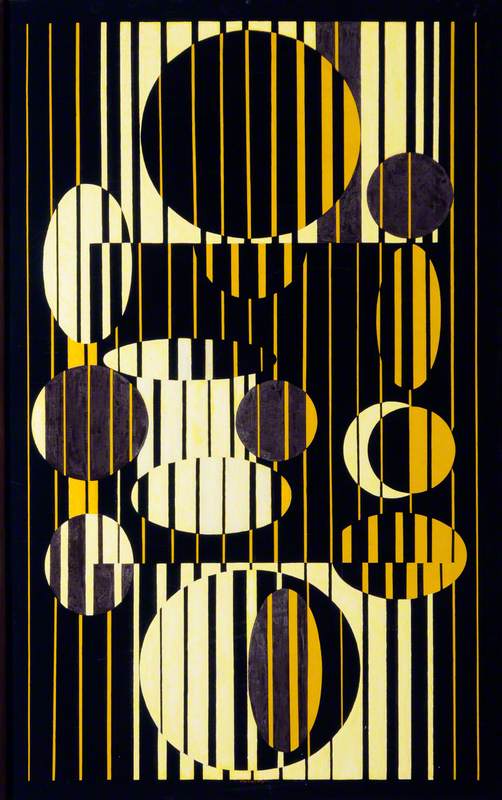

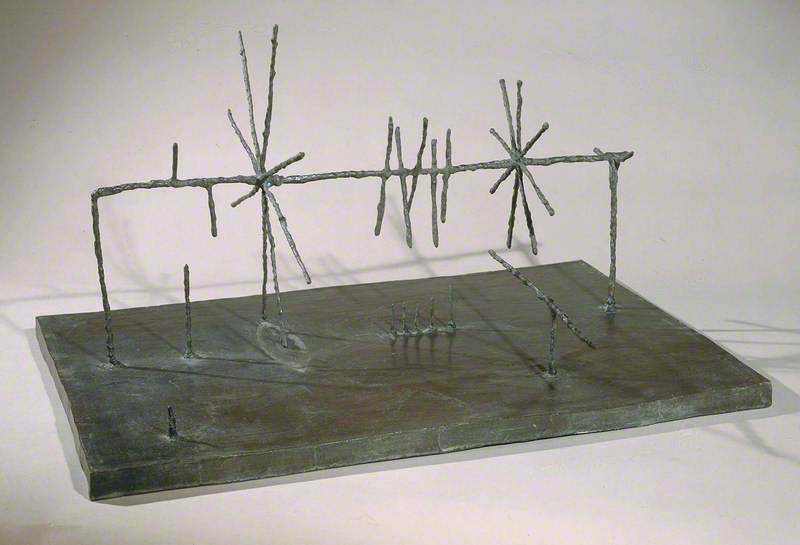

By the late 1950s, the artist was beginning to explore more systematically the ideas that became known as Op Art. At first, he sought more dynamism in his works, inspired by investigations in kinetic art, as with Iaca (1955–1957), an early example that is now a highlight of The Stanley & Audrey Burton Gallery at the University of Leeds.

Along with the fragmented diamonds of Taimyr (1958), you can easily grasp the sense of movement the artist was aiming to achieve in these asymmetrical compositions.

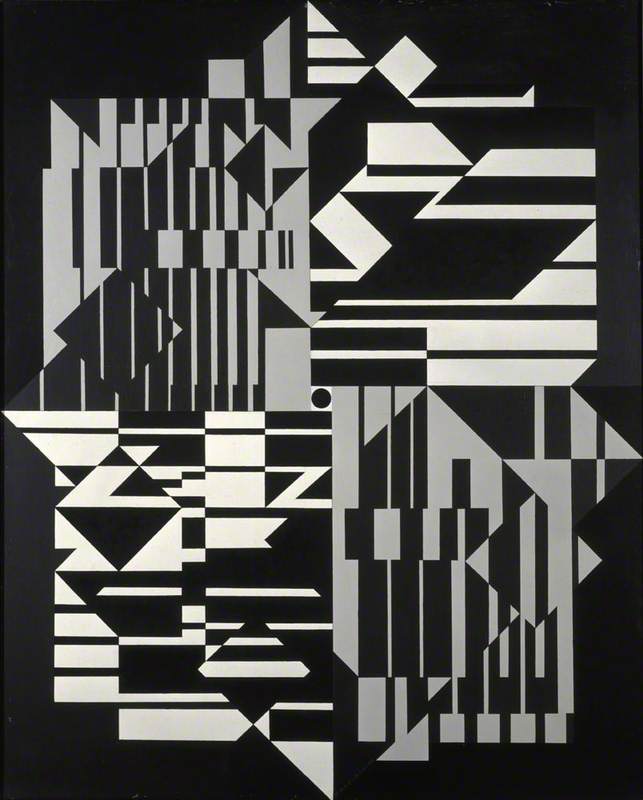

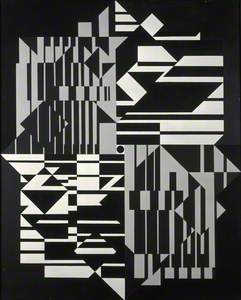

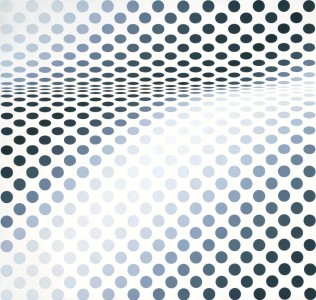

Vasarely's investigations of geometry, perception and movement continued with his black and white series. He devised this example, Supernovae (1959–1961), so that the image would appear to alter as the viewer moved in front of it. Depending on the angle, different sections appear to retreat or advance from the canvas, shifting in orientation or even changing in tone. The work also reflects Vasarely's fascination with cinema and photography – the artist executed each work in this series in both a 'positive' and 'negative' version.

With a title that suggests the excitement of the developing space age, Supernovae was originally conceived as a mural to be integrated into the outside form of a building. Vasarely desired to see his work placed outside galleries and in public spaces, leading to an interest in architecture, a field that he would become more involved in during the following decade.

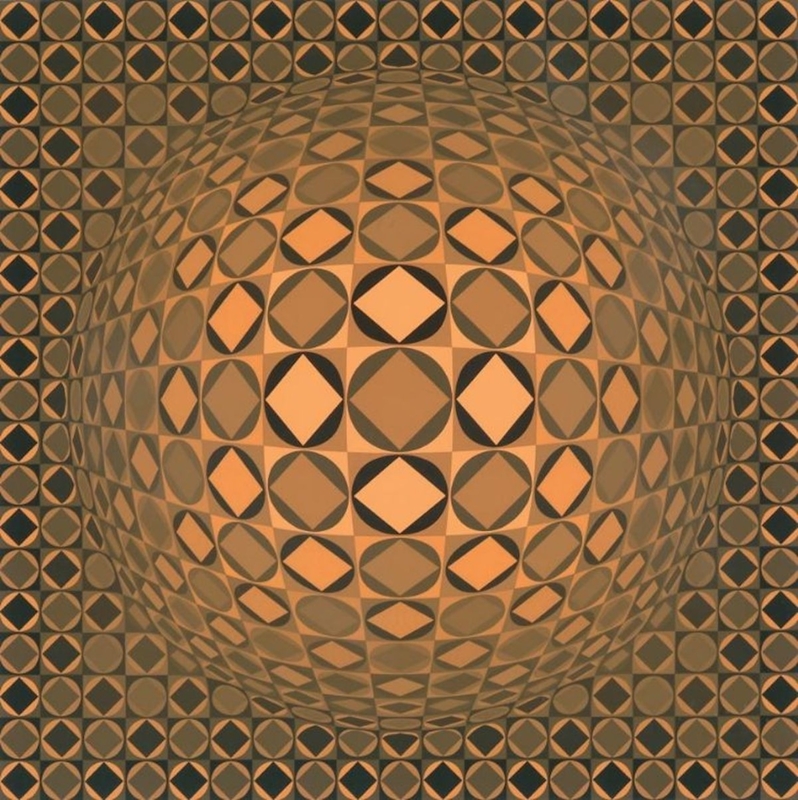

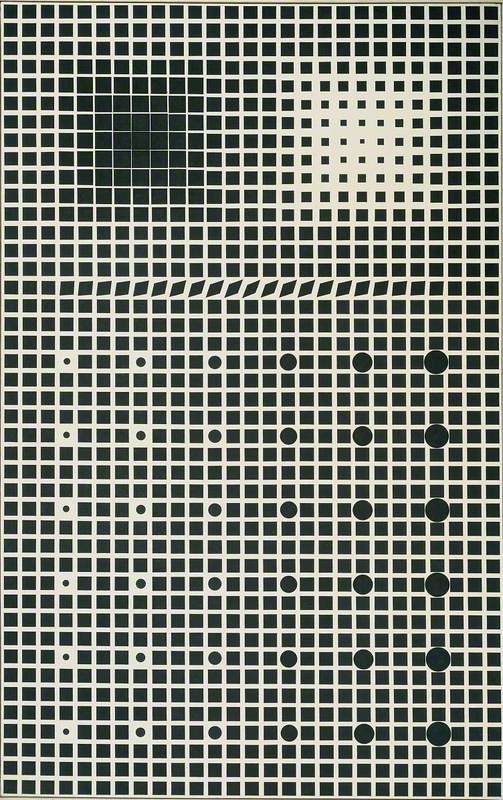

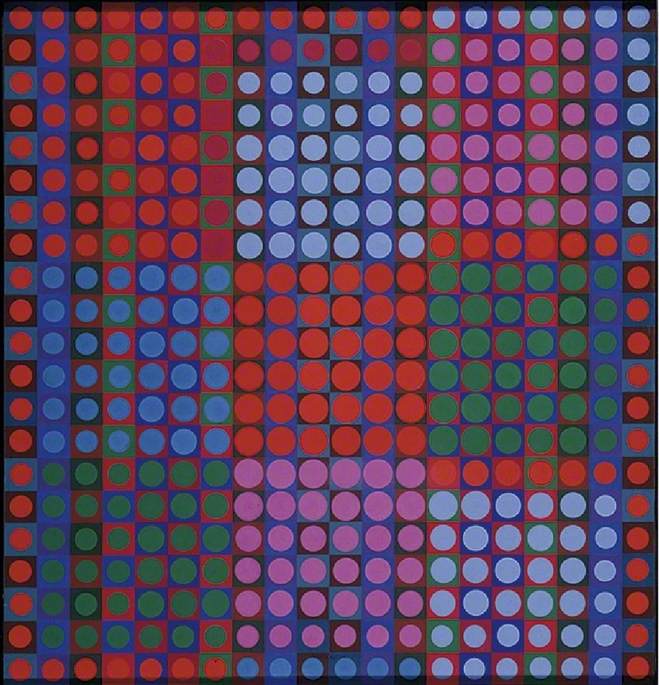

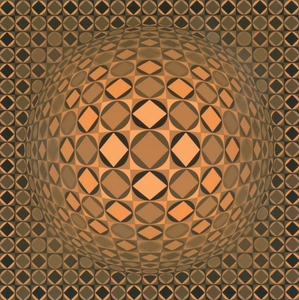

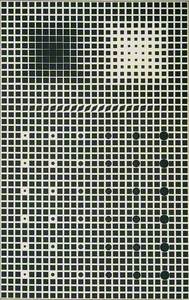

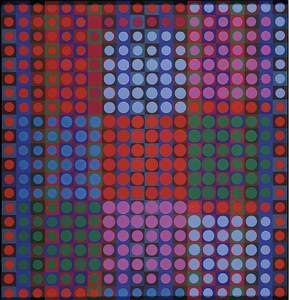

Vasarely was also simplifying his graphic language into a Bauhaus-inspired universal vocabulary he termed the 'Alphabet Plastique', a system of squares filled by a variety of geometric forms, whether smaller squares, or circles as seen in Kontosh (1964). As a genre, Op Art was christened in 1964 by Time magazine and quickly spread to become a signature look of the decade, from movies such as Casino Royale (1967) through mass media to the boutiques of Pierre Cardin and Paco Rabanne. By the end of this period, the artist was deforming these elements so that spherical forms appeared to explode from or recede into the plane, as in the abstract work at the top of the page.

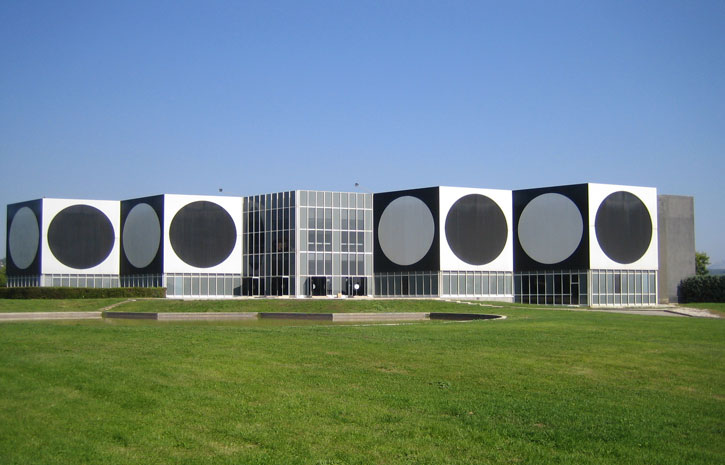

Fondation Vasarely, Aix en Provence

In the following decade, Vasarely turned his attention to his legacy. In 1970 he opened a museum dedicated to his work in Gordes, though this closed in 1996. However, In 1976, the French president Georges Pompidou opened the Fondation Vasarely in Aix-en-Provence, an institution dedicated to the Op Art founder designed by the artist himself – its facade forms its own monumental optical artwork.

While Hungary later set up museums dedicated to his work in Pécs and its capital, it is the Provençal foundation that preserves Vasarely's work and legacy with its permanent collection, exhibitions and cultural programme.

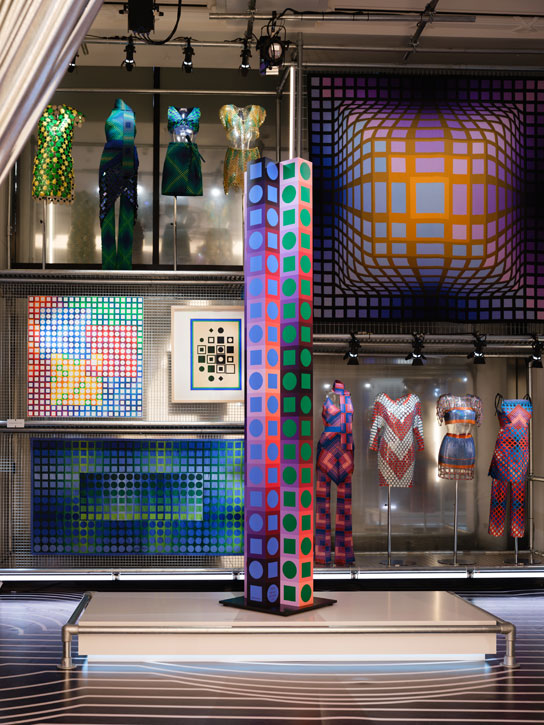

The Paco Rabanne collection at Selfridges inspired by Victor Vasarely

Recently, Paco Rabanne's creative director Julien Dossena worked with the institution to translate some of Vasarely's pieces into a 2022 fashion collection, accompanied by an exhibition at Selfridges London.

Looking at the artist's previous immersion in commercial art, it is hard to argue against such a collaboration. Indeed, his grandson, Pierre Vasarely, president of Fondation Vasarely, commented: 'Victor...stood for social art, the integration of art into the city and programmable art long before the age of computers. He was, above all, a visionary and utopian.'

Chris Mugan, freelance writer

'UNIVERSE', a collaboration between Paco Rabanne and Fondation Vasarely, is at Selfridges London until 31st March 2022