What connects eighteenth- and nineteenth-century anatomical illustrations with, among other things, 1950s collages and contemporary technology-inspired art? The answer lies in the intriguing concept behind a new exhibition at Glasgow's Hunterian Art Gallery.

The Hunterian's current show, 'Flesh Arranges Itself Differently', draws a line between the museum's own holdings and works from one of the UK's most important private modern art resources, the David and Indrė Roberts Collection.

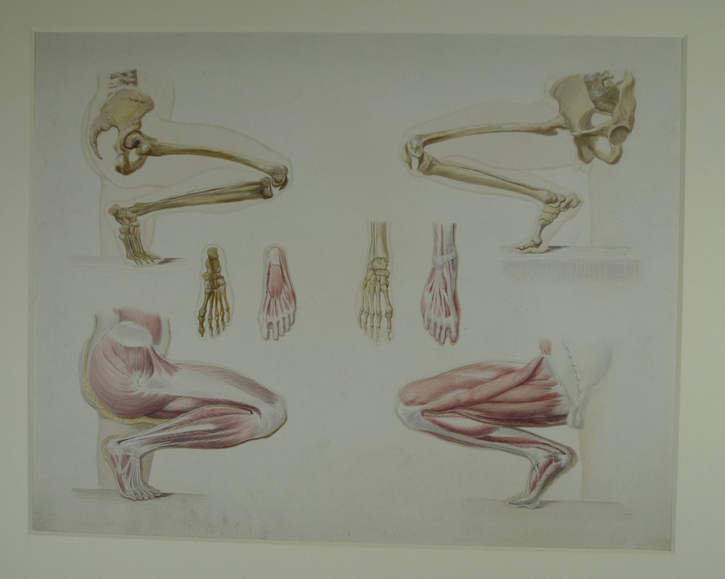

Écorché figure

by William Cowper (1666–1709)

What unites artworks from the likes of Robert Rauschenberg and Yayoi Kasuma with scientific inquiries of the Enlightenment is their shared concern with how we relate to our bodies, as well as to the world around us. For early anatomists, this came through discoveries about the workings of our flesh and blood, while modern artists have looked at our changing relationships with mortality, technology and spirituality.

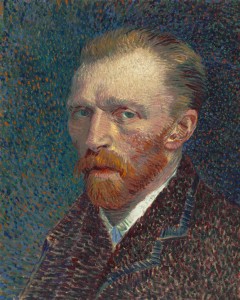

Of course, anatomical imagery has long been a fascination for those seeking to recreate the human form. Figurative artists have relied on knowledge of our interior workings – blood vessels, muscles and organs – to recreate ever more realistic representations of their subjects. As well as composing illustrations of body parts themselves, many have memorialised the work of the pioneers that made anatomy a science.

Here, the German Neoclassical painter Johann Zoffany portrays the renowned anatomist and physician William Hunter giving a lecture with the aid of anatomical and live models to members of the Royal Academy of Art – its founder Sir Joshua Reynolds is recognisable thanks to his ear trumpet. Scotland-born Hunter had founded the first private anatomy school in London, having learnt the practice of dissection on the Continent. He established an array of books and natural history specimens that later formed the basis of the University of Glasgow's Hunterian's collection. (Confusingly, his brother John Hunter's collection also formed the basis of a museum – the Hunterian Museum in London.)

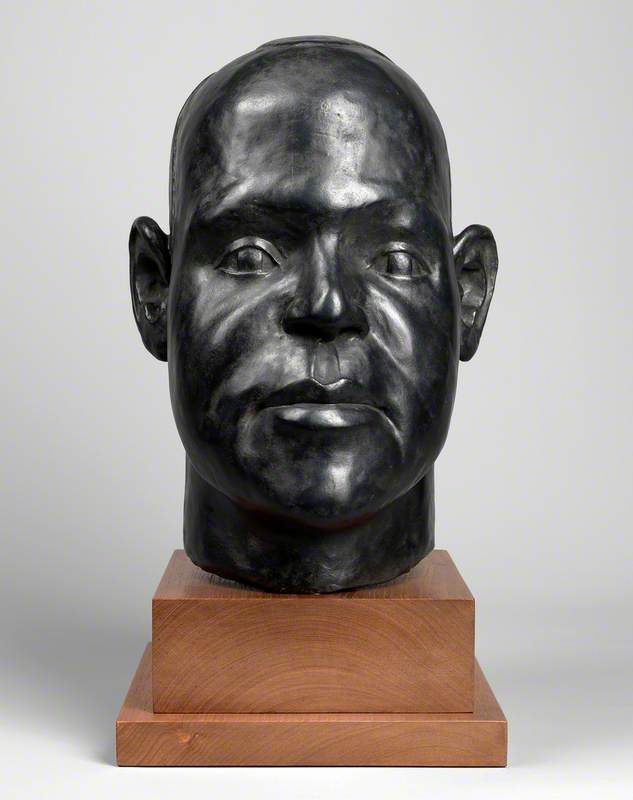

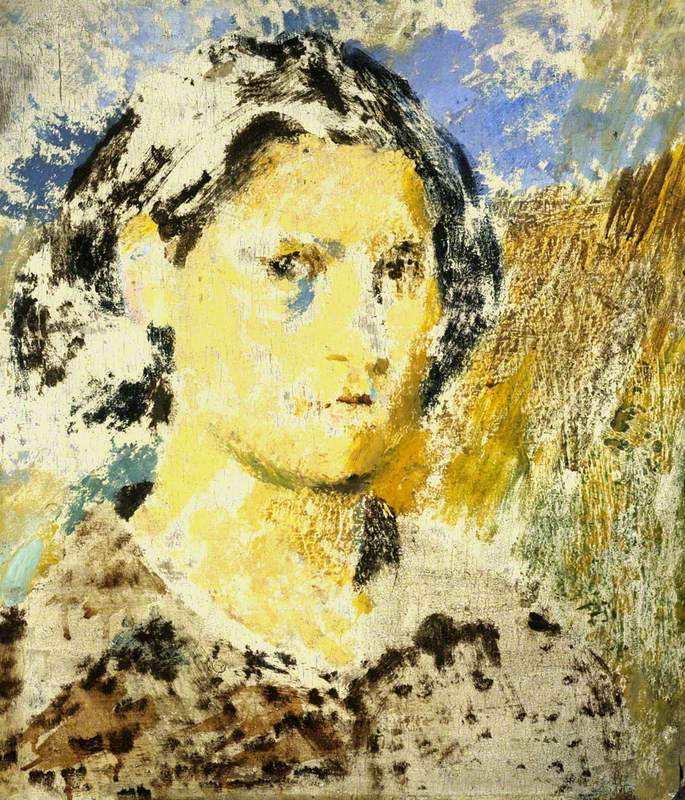

This period marked a key moment in the development of medical science and our understanding of the human body. Surgeons would break open corpses, divide them into pieces and separate the layers beneath the skin. Thus, the body became an object to be studied. As part of his collection, Hunter acquired works by the pioneering anatomist William Cowper. His work on dissection and preservation influenced Hunter's own patron and teacher, James Douglas.

Écorché figure

by William Cowper (1666–1709)

Zoffany's painting reminds us of the importance of anatomical knowledge to art education into the nineteenth century. A scientific analysis of perception was an integral part of the training offered by the nascent art schools, such as Glasgow, established in 1845. Here are examples of studies from casts made at the school in the latter half of the century by the landscape painter Robert Macaulay Stevenson from his early months of study there.

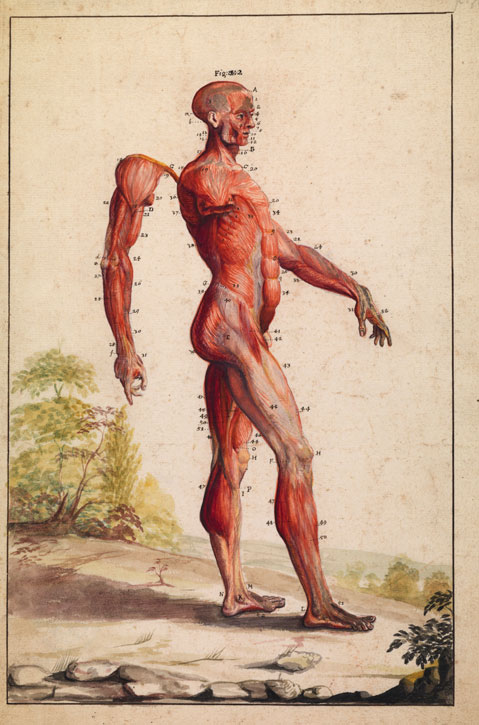

Anatomical studies of legs and feet

1874, watercolour & pencil on paper by Robert Macaulay Stevenson (1854–1952)

For the curators of this show, Ned McConnell and Dominic Paterson, the 'naturalism and neutrality of tone in these studies attest to the priority given to "ever-more-minute" visual analysis of bodily forms.'

We can also see Stevenson has been encouraged to look at the limbs as individual units rather than parts of a whole, a way of viewing that became ever more problematic during the twentieth century as the body was literally broken to pieces by industrial-scale warfare.

For artists that emerged after the Second World War, many seemed bent on putting the body back together, though not without leaving it disfigured in some ways.

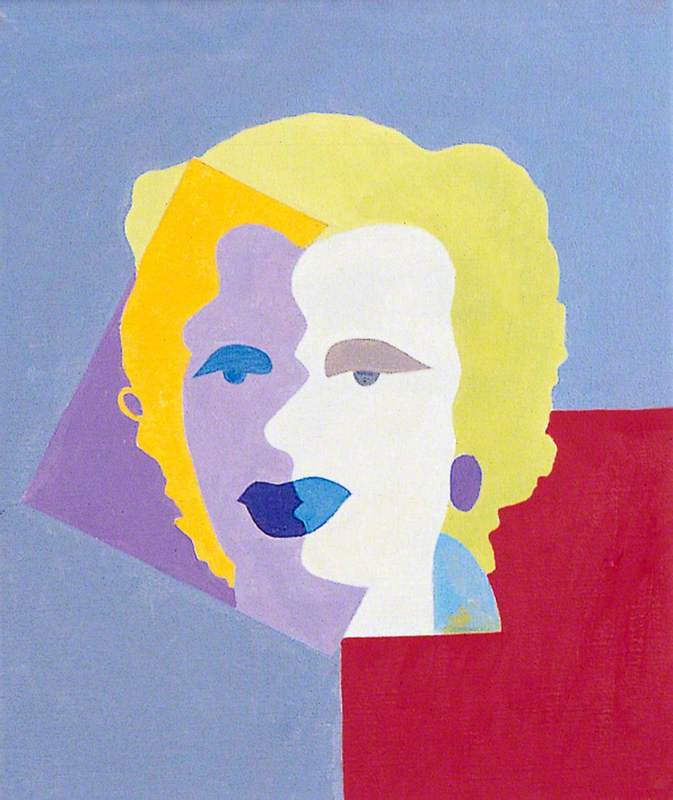

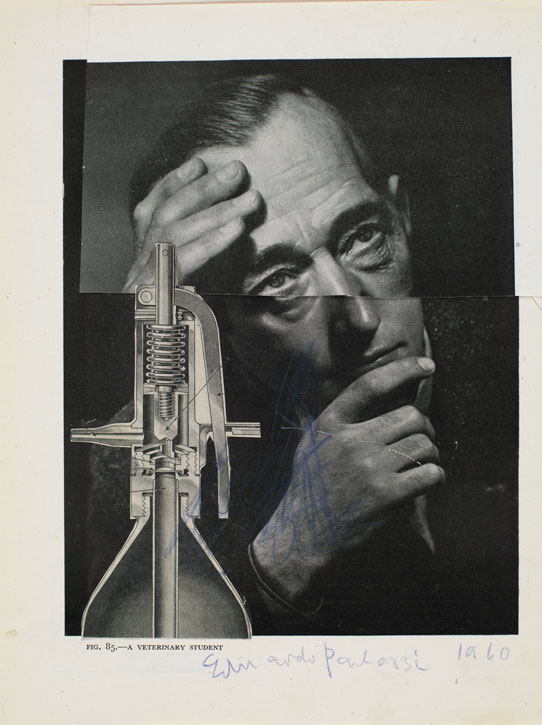

In his prints and collages, Eduardo Paolozzi augmented the human form with the detritus of mass culture and elements of modern technology. In A Veterinary Student (1960), the subject seems to be enmeshed with the apparatus of his chosen profession.

A veterinary student

1960, by Eduardo Paolozzi (1924–2005)

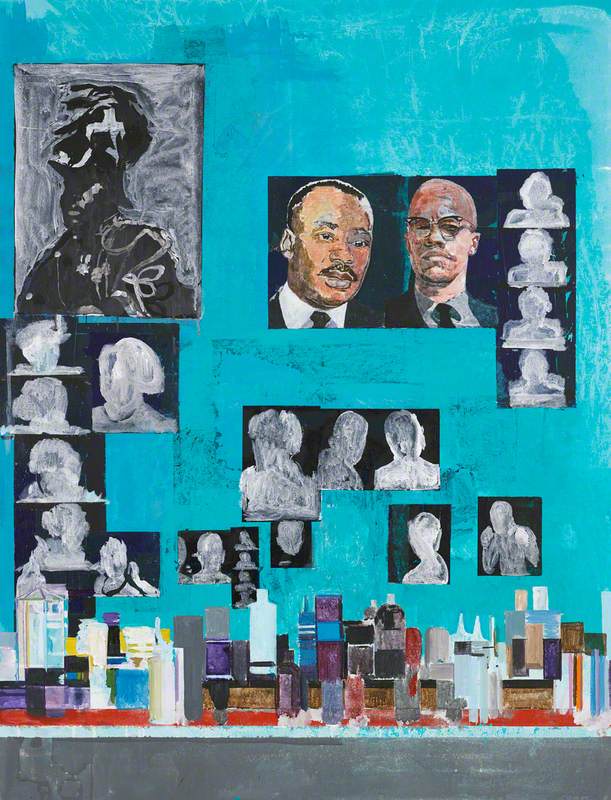

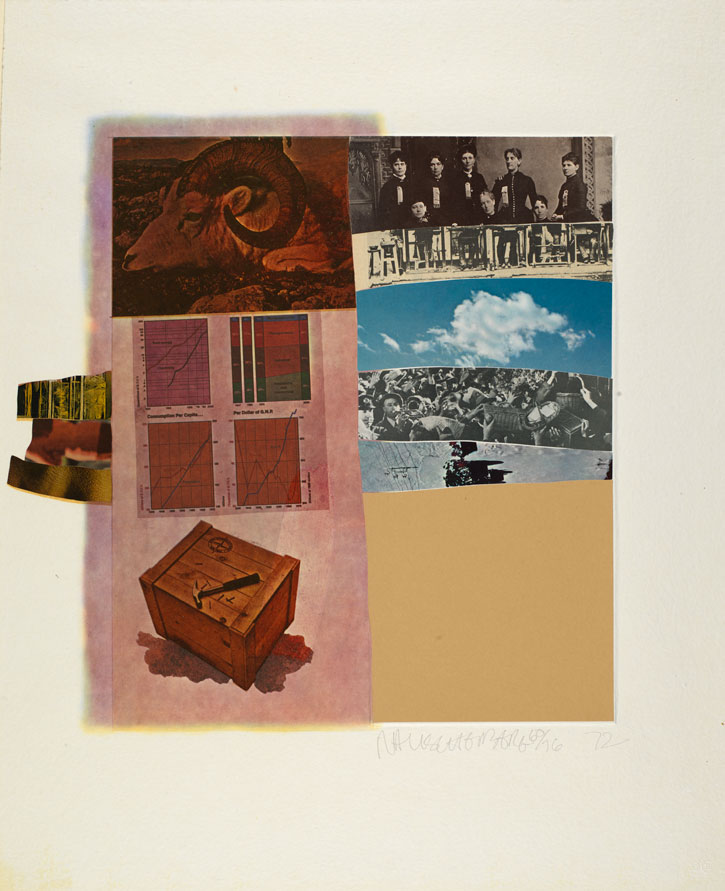

Other artists would avoid figurative imagery altogether, alluding to the more fractured experience of modern life and leaving us to free-associate among a disparate array of images. As was the case for US artist Rauschenberg, famed for his combines from the 1950s that brought together the disciplines of painting and sculpture. For his 1972 print series Horsefeathers Thirteen, Rauschenberg juxtaposed images of the natural world with technology and consumerism – revealing to us the confusion of our incorporeal lives.

Horsefeathers Thirteen I

1972, lithograph, screenprint, pochoir, collage & embossing on paper by Robert Rauschenberg (1925–2008)

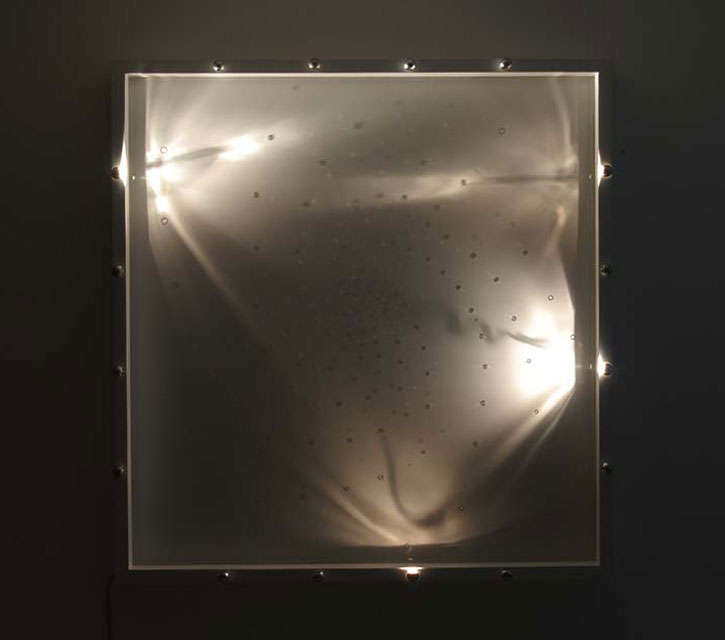

Another American artist, Lilliane Lijn, went further by breaking down the barriers between physical and immaterial forms, as seen in her kinetic and light-filled pieces. Lijn stated that she saw 'the world in terms of light and energy... my sculptures use light and motion to transform themselves from solid to void', hinting at the desire to escape into dreamworld or hallucinations. Cosmic Flares III (1966) is devised from a series of lightbulbs powered by motorised switches. Flashing inside a spiral lens, though, the surface is in a constant state of flux.

Cosmic Flares III

1965–1966, polymer lenses on perspex in painted wood frame, lights & motorised cam switches by Liliane Lijn (b.1939)

From the late twentieth century into the present day, artists have continued to look at the human form from the point of view of the forces applied to it rather than the body itself. Ilana Halperin is especially preoccupied with the relationships between personal experience and the natural processes occurring perhaps imperceptibly around us – the idea of deep time.

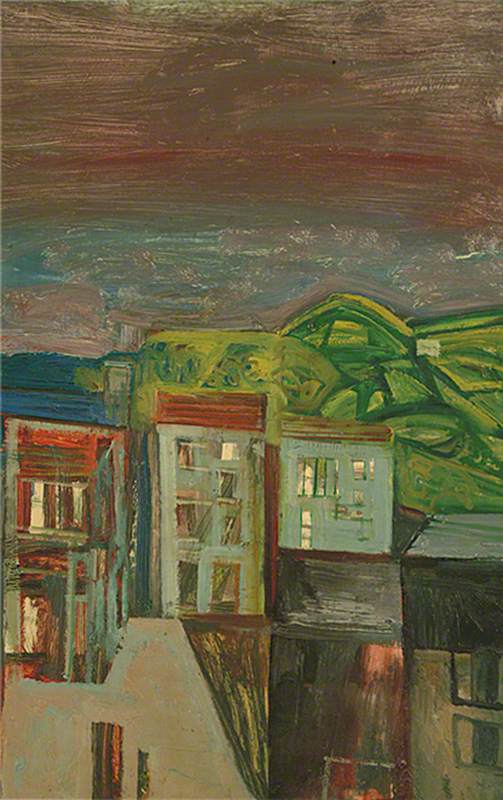

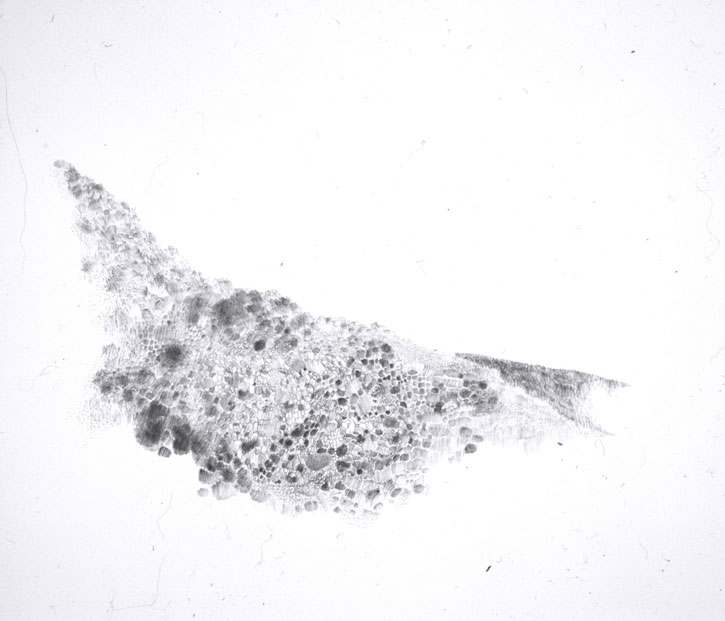

Halperin's concept of the 'autobiographical trace fossil', a means of relating to the world around herself, is illustrated by her project Nomadic Landmass (2005).

Nomadic Landmass (Eldfell)

2005, by Ilana Halperin (b.1973)

Here she documented her decision to mark her 30th birthday with a pilgrimage to the site of the Eldfell volcano in Iceland – formed also in 1973. Alongside sketches and photographs, the artist created a map-drawing that plotted her life in relation to this and other events, including the recent death of her father.

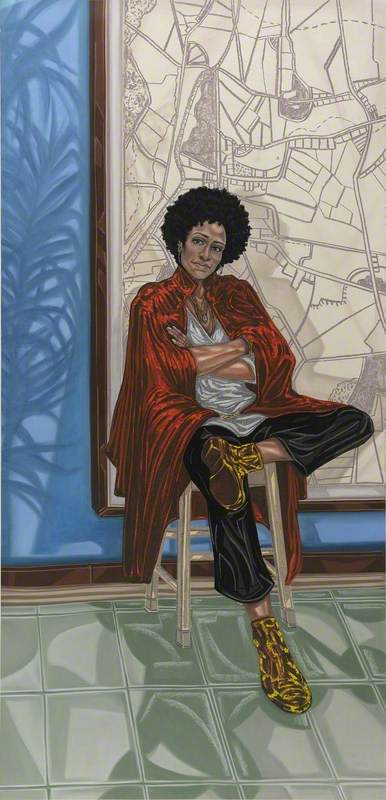

Yet anatomy continues to have a hold on one contemporary artist – another Scot, Christine Borland. Her work has developed a long relationship with the body, often in collaboration with experts in science and medicine. This began with the human skeleton she bought from a medical education supplies catalogue that became the starting point for her first solo exhibition at Tramway, Glasgow ('From Life', 1994).

Her 2010 video work Sim Woman is part of a trilogy featuring animatronic medical mannequins.

Since no female versions of these uncanny devices were then in production, seemingly a patriarchal oversight, Borland cast her own body in wax and overlaid this form on a male mannequin.

It is a reminder that even with advances in technology, we still need to think about the bodies we look at and the complex identities behind them.

Chris Mugan, freelance writer

'Flesh Arranges Itself Differently' is at the Hunterian Art Gallery, Glasgow, until 3rd April 2022