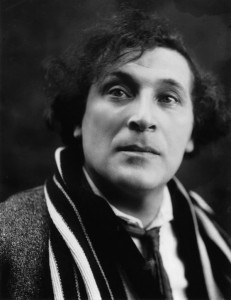

Marc Chagall (1887–1985) was described by the writer Henry Miller as 'a poet with the wings of a painter'. As an artist who preferred the company of writers, who wrote poetry and penned a dreamy memoir, it seems right to confer the title 'poet' on this most lyrical of painters.

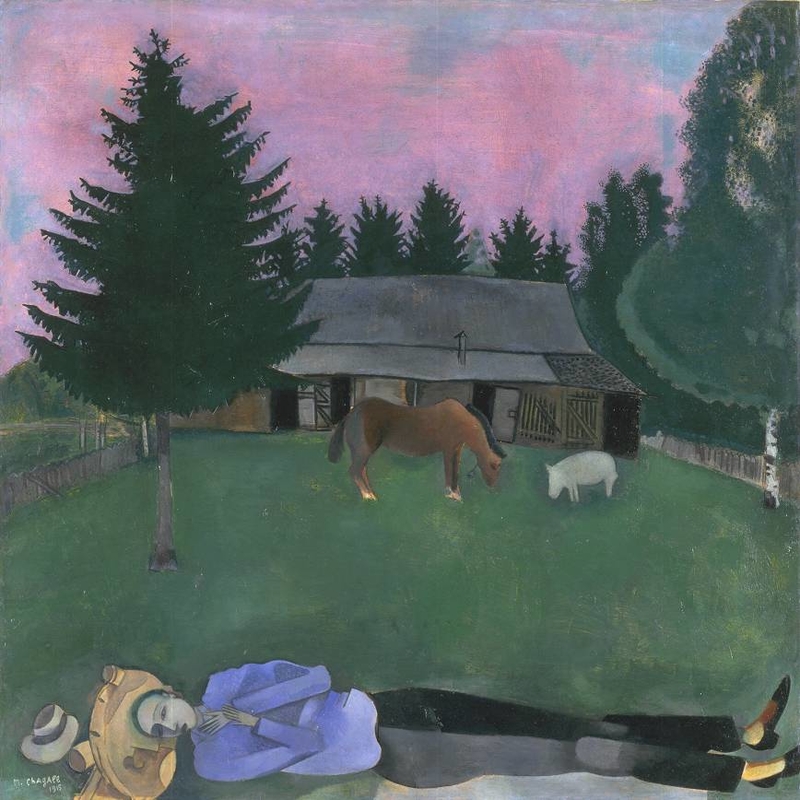

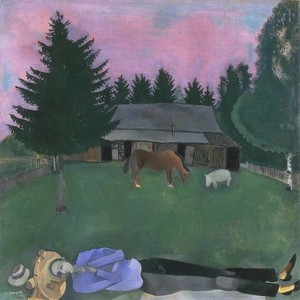

And it is commonly assumed that the figure in his 1915 painting The Poet Reclining, one of several works by the artist in Tate Modern, is Chagall himself. It is a view shared by his biographers Jackie Wullschlager and Jean Cassou, and further espoused by Stephanie Straine in the book that accompanied the exhibition 'Chagall: Modern Master' at Tate Liverpool in 2013.

This makes sense: Chagall was very fond of self-portraiture, and there's a line in his memoir which closely evokes the scene: 'Woods, pines, solitude. The moon behind the forest. The pig in the stable, the horse outside the window, in the fields. The sky lilac.'

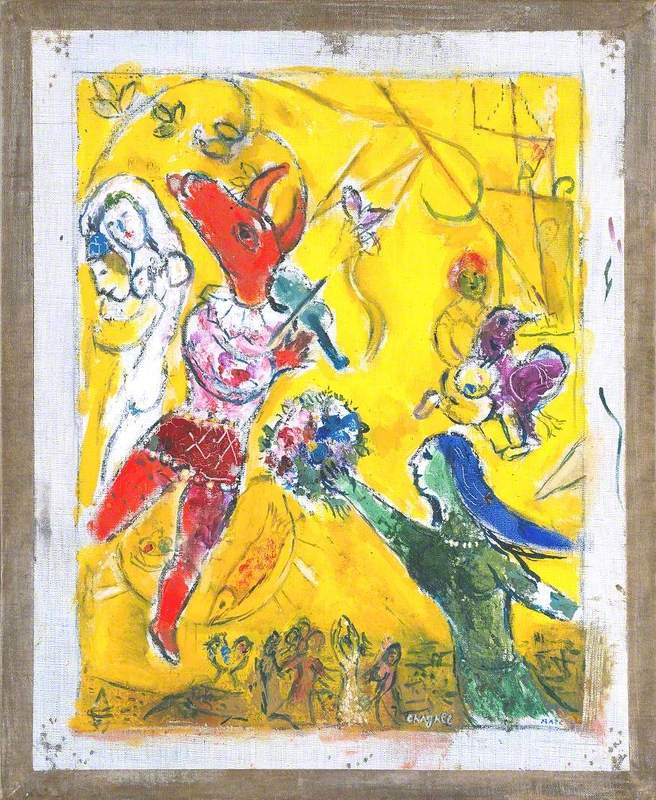

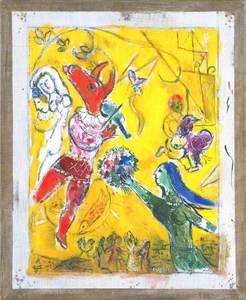

But this is an unusual Chagall, as compared to his other works, such as The Dance and the Circus. In The Poet Reclining, the landscape is plainly painted – there are no distortions, no flying animals, no rabbis with jet packs. Being a picture of dusk, the colours are muted. There's a horse and a pig in the field, their feet firmly on the ground, side on, almost cutouts, chewing the cud. The pig is ghostly, without features. Each animal stands before its shelter: the stable to the left, the sty to the right. Each will retreat there when the darkness falls further.

The Poet Reclining shows a sky of unforgettable lilac, just as Chagall described it. Its beauty never ceases to amaze. Turn away from the picture, turn back, and that lilac sky loses none of its force. That dusk is the other wonder, captured as it falls in shades of deepening green.

Chagall painted it when he was on honeymoon in the peaceful setting of his in-laws' dacha in the countryside near his home town of Vitebsk, in present-day Belarus. He had just married Bella Rosenfeld and his passion for her is clear in painting after painting, made over many years.

Often their love finds expression through weightlessness and flight. In The Promenade (1917–1918), Chagall holds on tight to Bella's hand lest she flies away like an untethered kite. In Above the City (1914–1918), they cross the sky like Superman and a rescued Lois Lane. Daniel E. Schneider's psychoanalytic study of his art remarks that for Chagall 'the act of flying is the act of love'.

Years later, Chagall mourned the death of Bella in Bouquet with Flying Lovers, completed in 1947.

Yet in The Poet Reclining, the poet is flat on his back, not upright, not flying. The opposite of flying, in fact. He might be dead – his arms are crossed on his chest, and although his eyes are open, they are dead eyes in a mask-like face, and the face has a sickly, deathly pallor.

This poet seems in despair in the countryside. He's taken off his hat and coat and submits himself to the chill of the evening. His hands seem to reach for his throat as though he is choking on the pine-scented air.

This desperate figure makes for a strange Chagall self-portrait. There is no physical resemblance, for sure, but more importantly, this is a joyless figure, a man in torment, not at all a happy newlywed. (Here, we must take issue with Wullschlager's view of the painting as the 'happiest of all his self-portraits', a claim questionable in both respects. For good measure, she identifies the white pig as a goat.)

We should think of this man, this poet, as someone who is denied Chagall's idyll, a man without a lover, without solace. Then the darkening wood would seem less appealing, the onset of night something to fear.

Chagall had originally painted Bella lying next to the poet, but painted over her. And indeed the faint trace of a long dark shape, including the vague silhouette of a head and a foot, can be seen above and alongside him, in what Michael R. Taylor describes as 'a ghostly pentimento in the grass'. In so doing, Chagall turned the painting from what was likely a celebration of the loving couple to one in which the male figure is left alone and in distress.

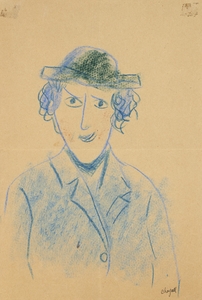

The Poet with the Birds, Marc Chagall, 1911 https://t.co/P44VfRpfJV #marcchagall #minneapolisinstituteofart pic.twitter.com/0KelCJBVVL

— Marc Chagall (@artistchagall) January 17, 2021

Four years earlier, while living in Paris, Chagall painted a very similar scene. In The Poet with the Birds (1911), the recumbent poet is in an almost identical position and looks up at three white birds perched in a tree. The mood here is very different. It's a spring or summer day and the trees are in blossom. The poet, moustachioed and with floppy red hair, seems to be smiling up at the tree. His hands are crossed at his waist and he appears relaxed.

Perhaps Chagall remembered this earlier painting when he was on honeymoon among the pines, and produced a new version of it, replacing the contented poet with an altogether less happy man: a poet faced with nature, and nothing else but his artistic response to it.

Consider what the two poets are wearing. In the later picture, The Poet Reclining, his formal clothes are those of a town dweller. They mark him out as an alien here, emphasising his discomfort. In contrast, his happier antecedent wears the red smock and heavy boots suited to country living.

If the later poet 'seems oddly isolated' because the First World War was being fought not so far away, as the Tate's display caption claims, Chagall himself appears not to have felt much of an urge to participate. He might have felt guilty, with the war 'rumbling over' him, but following his honeymoon he first tried to return to Paris (where he had lived between 1910 and 1914) and then avoided active service by taking a clerical job in his brother-in-law's office in Petrograd. Trapped by the war, he wrote that 'Europe closed before my very eyes'.

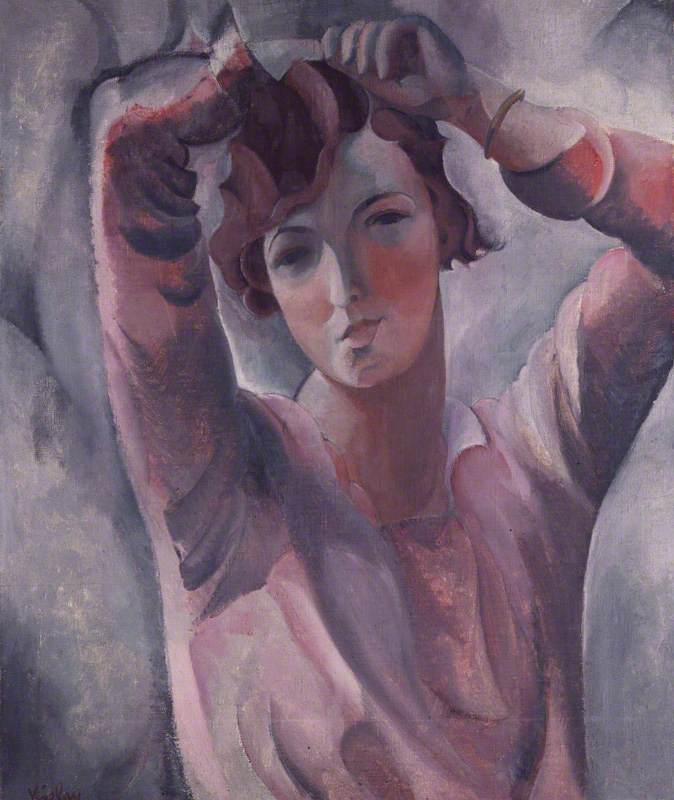

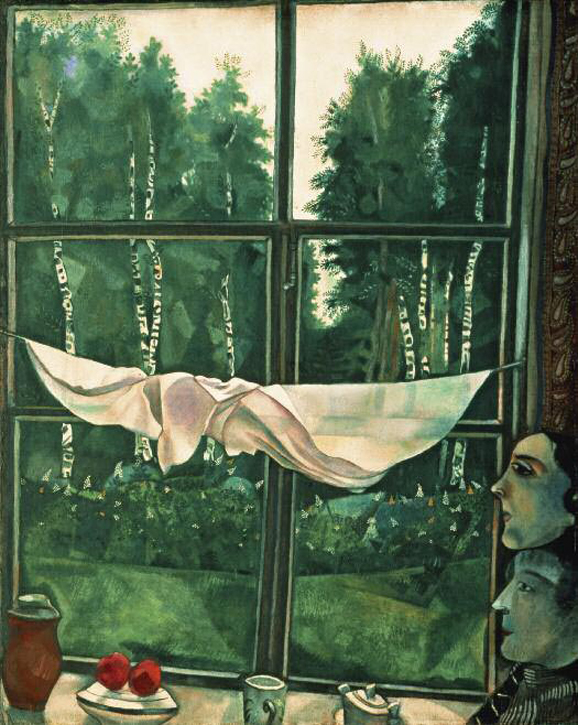

Window in the Country

1915, gouache & oil on cardboard by Marc Chagall (1887–1985)

Chagall's fascination with the forest is plain to see in Window in the Country (1915), painted during the same stay, in which he and Bella stare out at the trees surrounding their cabin. Their expressions give little away, but the view affords no obvious pleasure. Those dark trees reach high and hem them in. The curtain has been folded on itself to let in light and allow them to see out. We might assume that they bothered Chagall, those tall trees, for they restrict and dominate, and he is a painter of panoramas, of bird's-eye views, of brilliant colour, of movement and freedom.

The Poet Reclining is not a self-portrait, at least not a conventional one. This mask-faced man is a generic type, or a ghost of a man. He has no blood in his veins. In fact, he is not a particular man at all, but a type, or a condition, of man. He is what results when love is missing, Chagall seems to say. At the moment of Chagall's greatest happiness – at least the selfish happiness of the honeymooner – the artist could not forget what might have been, had life worked out differently: the heights of his own joy have brought to mind its opposite.

In recognising how fortunate we are, a fear might creep up on us, as forbidding as a forest, that we might lose what we have.

In one of his poems – In Lisbon Before Departure – written at a time of despair, Chagall refers to the loss of his own identity:

Have you ever seen my face –

In the middle of the street, a face with no body?

There is no one who knows him,

And his call sinks into the abyss.

Adam Wattam, writer

Further reading

Monica Bohm-Duchen, Chagall, Tate Publishing, 2001

Marc Chagall, My Life, Peter Owen, 2003

Simonetta Fraquelli, Chagall: Modern Master, Tate Publishing, 2013

Daniel E. Schneider, 'A Psychoanalytic Approach to the Painting of Marc Chagall', College Art Journal 6, no. 2, 1946

Michael R. Taylor, Paris Through the Window: Marc Chagall and his Circle, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 2011

Jackie Wullschlager, Chagall: Love and Exile, Allen Lane / Penguin Books, 2008