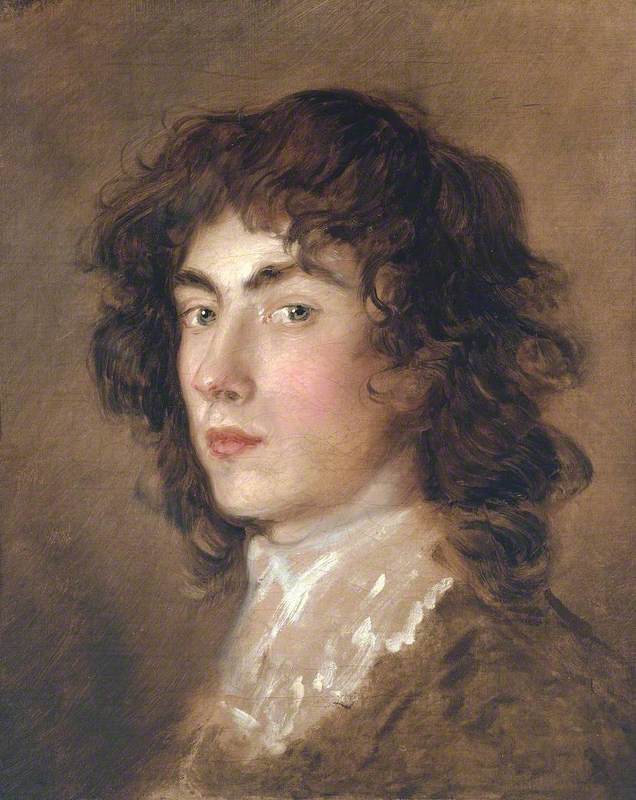

Johann Zoffany is perhaps not the most famous of artists today. During his life, however, he was a celebrated painter and a founder member of the Royal Academy. He mixed with royalty, celebs and generally lived the good life, possibly a little too much.

As you can read in this story, he was born in Frankfurt, trained in Regensburg and Rome, and moved to London around 1760. This coincided with the Hanoverian king George III ascending the throne. This sense of a shared German heritage was to prove useful for Zoffany. He moved to a house on the opposite bank of the river to the royal residence of Kew Palace, and promptly gained himself an introduction. He became particularly friendly with Queen Charlotte. Royal commissions followed, many of which are still in the Royal Collection.

The Story Behind The Tribuna Of The Uffizi By Johan Zoffany https://t.co/QkUAjKVeXc I wonder how many artworks can you recognize?@RCT pic.twitter.com/6HKxVxk1je

— dailyartmag (@DailyArtMag) February 19, 2018

The last work he painted for the royal family was The Tribuna of the Uffizi, a truly astonishing piece that faithfully reproduces a number of Italian masterpieces, as well as a selection of nobles on their Grand Tour. Sadly, he had spent too long on it, and ultimately the queen hated it!

Mary Wilkes; John Wilkes

exhibited 1782

Johann Zoffany (1733–1810)

He was also known – and made a fortune off the new middle classes – for painting ‘conversation pieces’. These were relatively small informal group portraits, often of a family group or a circle of friends. This genre became popular in Britain from about 1720. The group was usually apparently engaged in genteel conversation or some activity, very often outdoors.

But here we’re not interested in Zoffany as a royal painter or as a kind of eighteenth-century middle-class Instagram filter. We’re going to take a look at his portrayals of what we today might see as some of his more unusual subjects – even if many of them could be considered variations on the conversation piece genre.

A new stage in his career

When Zoffany first came to London, he managed to become acquainted with the circle of David Garrick (1717–1779), the most famous actor of the age. Even today, you can see plays at the Garrick Theatre (on Charing Cross Road, actually opened in 1889), walk up Garrick Street and – if you’re of that persuasion – become a member of the Garrick Club. It’s a measure of what a big deal he was that so many things are still named after him.

Garrick, Ackman and Bransby in a Scene from Lethe

1766

Johann Zoffany (1733–1810)

Two Sketches of David Garrick as Abel Drugger in 'The Alchymist'

Johann Zoffany (1733–1810)

Shuter, Beard, and Dunstall in 'Love in a Village' by Isaac Bickerstaffe, Covent Garden, 1762

c.1767

Johann Zoffany (1733–1810)

In the first decade of his residence in London, Zoffany undertook a series of paintings of Garrick and other actors often in character, giving us a fascinating glimpse into the world of Georgian theatreland. You could see these as ‘theatre conversation pieces’, but really they glorify the profession of acting.

David Garrick as John Brute in 'The Provok'd Wife' by Vanbrugh, Drury Lane, 1763

1763/1764

Johann Zoffany (1733–1810)

With the popularity of these works and the royal patronage, it was no surprise that Zoffany became a founder member of the Royal Academy in 1768.

Scientists, artists and connoisseurs

Sometimes seen as a kind of conversation pieces, these next works take a look at intellectual and cultural life in Georgian society.

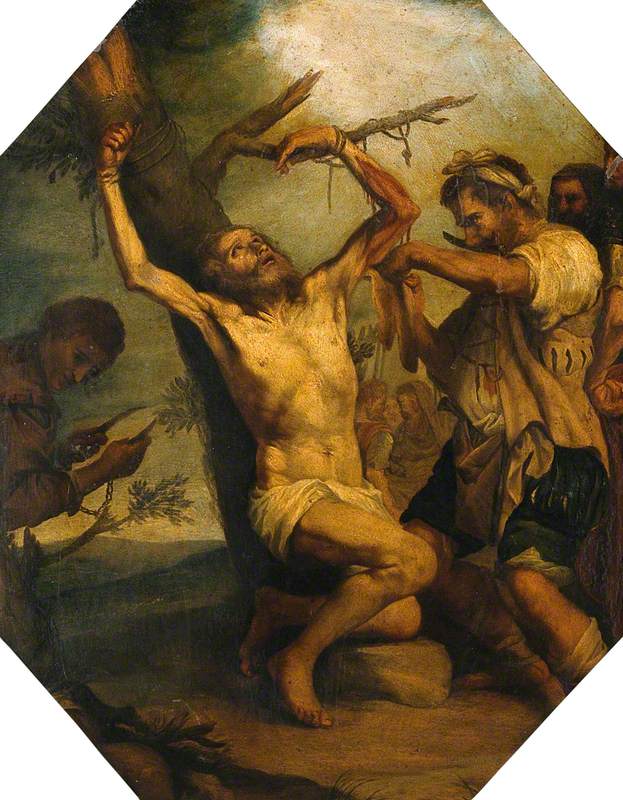

This unfinished painting depicts a life class at St Martin’s Lane Academy, which had first been established in 1720. The Academy was a kind of forerunner to the Royal Academy of Arts. You can see some casts of ancient statues in the background, which would have also been used by students as part of their training. Zoffany painted this in the early 1760s, before the Royal Academy was founded.

William Hunter (1718–1783) was a Scottish-born anatomist and surgeon. He lectured on surgery and later anatomy, which became his chief interest. This painting shows one of his anatomy lectures at the Royal Academy of Art, with anatomical and live models. The man with an ear trumpet is Sir Joshua Reynolds. Hunter was appointed physician-extraordinary to the Queen. He established a superb library and collection of medals and natural history specimens which became the collection of the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow. Hunter was the older brother of John Hunter, also a surgeon – the museum of the Royal College of Surgeons of England is named after him (also confusingly called the Hunterian!).

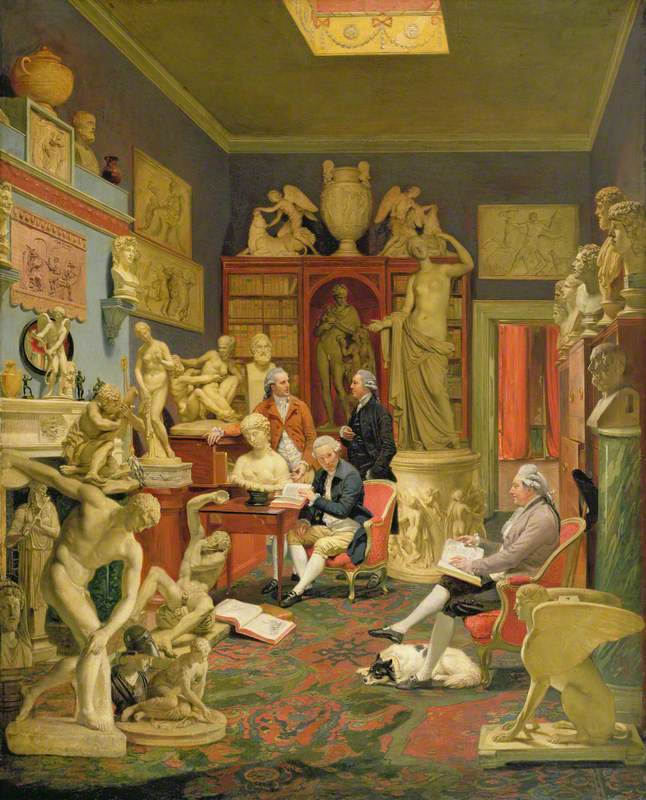

Charles Townley and Friends in His Library at Park Street, Westminster

1781–1790 & 1798

Johann Zoffany (1733–1810)

This a group portrait of Charles Townley and friends. Townley was a collector and a trustee of the British Museum – many of his pieces ended up there. Townley is sitting in his library, his dog asleep at his feet, in conversation with baron d'Hancarville, who sits in a red chair. The other two men are Sir Thomas Astle and Charles Greville. The painting is an elaborate fiction. In reality, Townley's collection was distributed throughout the house but here it has been collected together. This way it demonstrates d'Hancarville's theories on the evolution of classical art, in a similar vein as Zoffany's painting of the Uffizi.

Originally painted in the early 1780s, Zoffany was asked to amend it in the 1790s. The discus-thrower (also known as The Townley Discobolus) was not discovered until 1791, but it was considered so important that it just had to be in the painting. Fun fact: the discus-thrower's head has been restored incorrectly – the Greek bronze original had the head looking back towards the discus. The repainting was undertaken after Zoffany returned from... India!

A passage to India

This is one of Zoffany’s most famous works. It's called Colonel Mordaunt's Cock Match. But how did he come to paint this? When he returned from Italy, he was out of favour with the British royals, and the fashion had moved on from conversation pieces. So he thought it would be a splendid idea to go to India. He stayed a few years, created some fascinating works, and then returned to London.

These two portraits are of the Nawab of Oudh, Asaf-ud-Daula, and his minister, Hasan Reza Khan, both of whom are to be found in Colonel Mordaunt's Cock Match. In the portrait, Asaf's dress is white muslin, with necklaces and armlets of pearls, rubies and uncut emeralds, and he wears a red turban. Asaf's court at Lucknow was extravagant, attracting many European adventurers lured by money and an exotic lifestyle. Zoffany was just the sort of man who would be enticed by this prospect – true to form, he gained a mistress and a family during his stay.

Major William Palmer with His Second Wife, the Mughal Princess Bibi Faiz Bakhsh

1785

Johann Zoffany (1733–1810)

These next two works feature people from India in the setting of a conversation piece. The first is a striking group portrait of Major William Palmer (1740–1816), with his wife, Bibi Faiz Bakhsh ‘Faiz-un-Nisa’ Begum (d.1828), on his right and her sister Nur Begum on his left. Palmer was a friend of Warren Hastings and was at the Lucknow court at various times between 1782 and 1785 as Hastings’ confidential agent for the extraction of loans from the Nawab. His will described his wife as ‘his devoted companion of more than 30 years’. In the early days of the British in India, this relationship was able to be celebrated in art – something that would have been highly unusual later on.

The second group portrait is of William Blair’s family. Blair was a Colonel in the East India Company. One of his daughters is feeding a cat held by an Indian girl. The girl is described in the title as an ayah, a girl or woman employed by a family to clean, look after children, and perform other domestic tasks. In the background are three paintings, two of which depict Indian customs which fascinated and horrified Europeans – preparation for a suttee, the burning alive of a widow, and Charak Puja, a religious ritual in which a man is suspended by a wire.

Together these works show the complex relationship between India and Europe that was already in progress, before the even greater upheavals of the nineteenth century and the seizing of power by the East India Company.

As with the ever-quirky Zoffany though, there was a tall tale to add to his return journey. It was reported (although not totally verified) that he was shipwrecked on the Andaman Islands on the way home, and the surviving sailors drew lots to see who would be eaten! If this story is true, as William Dalrymple remarks in his book White Mughals, Zoffany was the first (and last) Royal Academician to have become a cannibal. As usual with Zoffany though, this particularly gruesome dish should be served with a large amount of salt!

Andrew Shore, Head of Content at Art UK

You can find out more about Zoffany in this episode of BBC Four's Britain's Lost Masterpieces.

Plus, see what Zoffany works are available in our online shop.