In the introduction to This Dark Country: Women Artists, Still Life, and Intimacy in the Early Twentieth Century (2021), Rebecca Birrell asserts that her fixation with the still life genre was due to 'its capacity to produce and accommodate intimacy, an affective power other genres simply could not provide'. For Birrell, the 'oranges, lemons... lilies, cups of tea' she observed in the work of Vanessa Bell, Dora Carrington and Gwen John, among others – were much more than they appeared: 'they were histories of women's lives compiled by way of the objects that bore witness.'

'Life is Still Life' at The Women's Art Collection

'Life is Still Life' – the current exhibition at The Women's Art Collection (housed at Murray Edwards College, University of Cambridge) – presents a series of modern and contemporary still life works made between 1940 and today, from artists such as Margaret Thomas, Shani Rhys James and Joy Labinjo. For curator Naomi Polonsky, the exhibited artists all 'engage with the history of still life as a genre, while also commenting on pressing current issues including climate change, the pandemic and the legacies of colonialism.'

In her text for the show, Polonsky also identifies how still life was dismissed as a 'low genre' within art history, despite it being a site for 'radical experiments with form and meaning and a way for artists to explore broad questions about life, death, gender and the self.' She explains how women artists were caught in a double bind in the twentieth century, being restricted and then denigrated for their choices.

If they attended art school, they would have turned to still life due to the fact they couldn't attend the life drawing lessons focused on human anatomy and were denied access to nude models. Without mastering anatomical form, any work depicting the figure would be dismissed as amateurish, which therefore precluded them from painting 'high genre' canvases, such as portraiture, history or religious painting.

Perfect by Nature for Gift and Centrepiece

2022, oil on canvas by Joy Labinjo (b.1994)

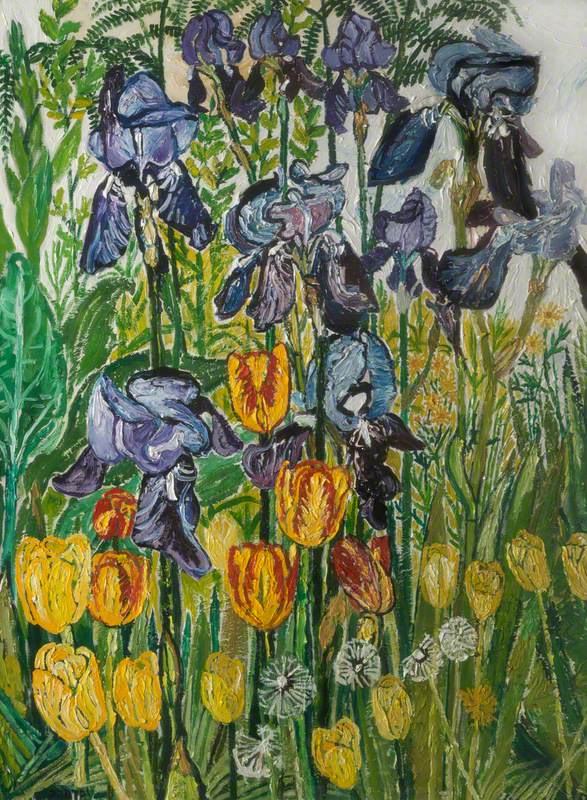

As a result, the still lives made by women artists often exuded a quiet radicalism. Despite their deceivingly straightforward subject matter, these paintings often contained references to biographical details or subjective interests, and have been interpreted through questions of gender, identity and the relationship between the public and private sphere.

'Paradoxically, the prosaic nature of its subject matter meant that still life has been the ideal genre for artistic experimentation,' writes Polonsky. 'The artworks [in the exhibition] contend with the tensions at the heart of still life... They freeze moments in time or create a dynamism that challenges the idea of 'stillness'. They integrate paintings-within-paintings or self-portraits, blending different genres.'

Still Life with Pears

c.1954, oil on canvas by Maeve Gilmore (1918–1983)

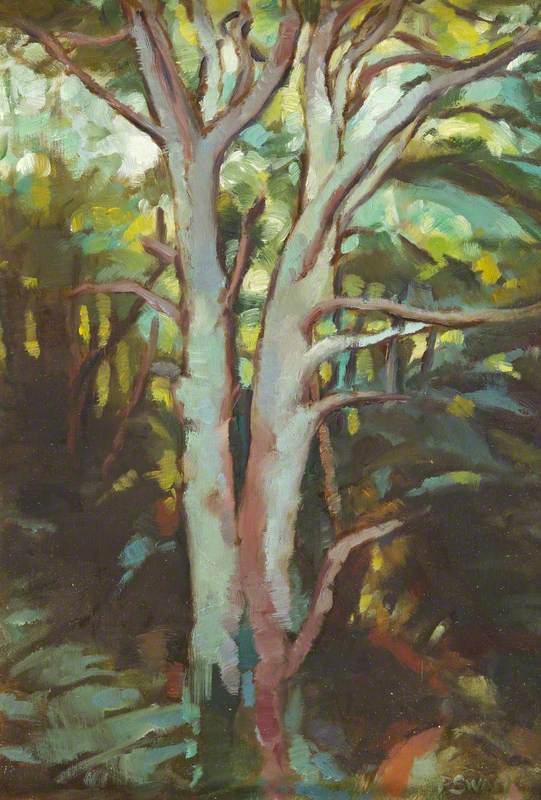

The exhibition includes Maeve Gilmore's paintings of pears, made in 1949–1950, while she was pregnant and in early labour with her daughter Clare. In Gilmore's memoir, A World Away (1970), she recalled, 'I went to my painting room, and started painting a still life, which under the circumstances doesn't seem quite appropriate.'

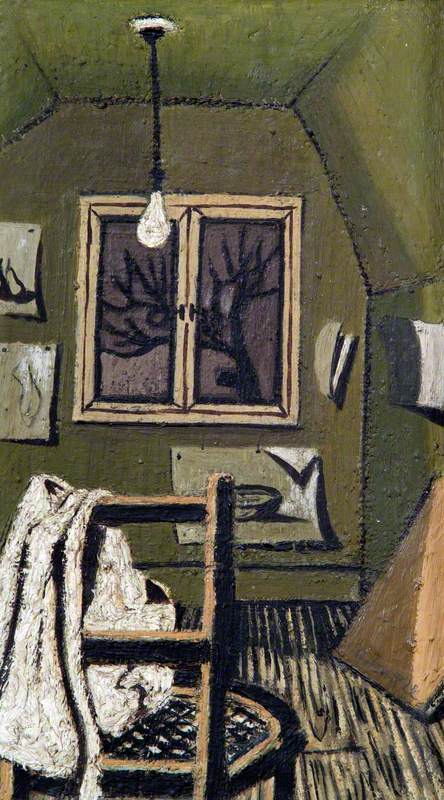

Albeit invisible to the viewer, the memory of her daughter's birth is indelibly linked to this bowl of fruit. Fruit and vegetables – particularly pears, apples and onions – recurred in her practice, along with other domestic and playful scenes of family life and animals. In the recent Gilmore retrospective at Studio Voltaire in London, the curators identified her 'distinctive compositional instincts... [using] doorways and windows as framing devices', which is particularly evident in the oil on canvas painting Attic Room.

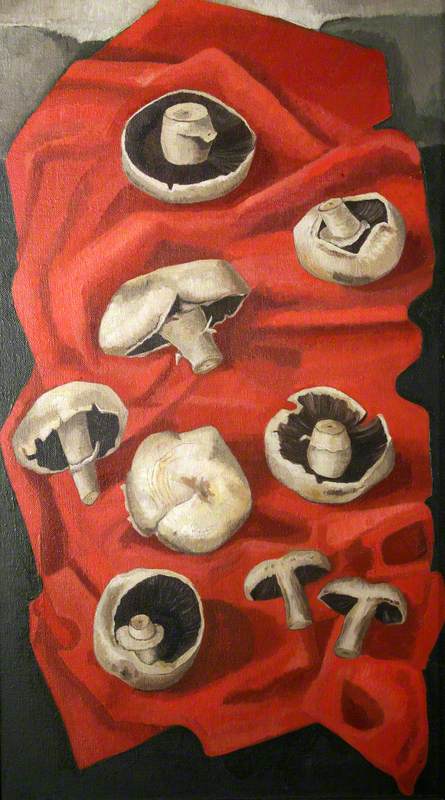

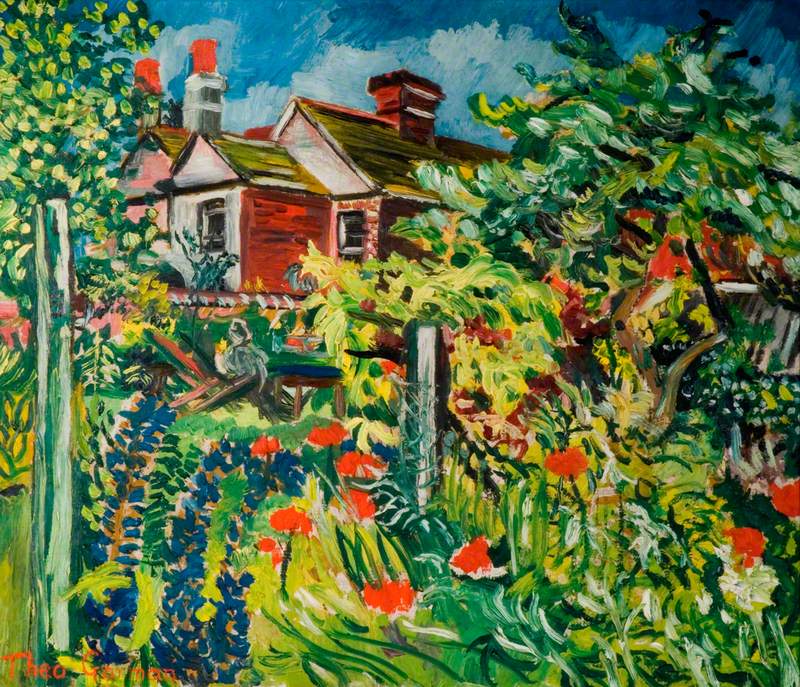

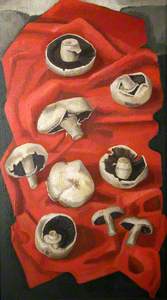

While Arlie Panting's figurative paintings have an ethereal quality, her still life paintings are rendered with a bold and heightened graphic style.

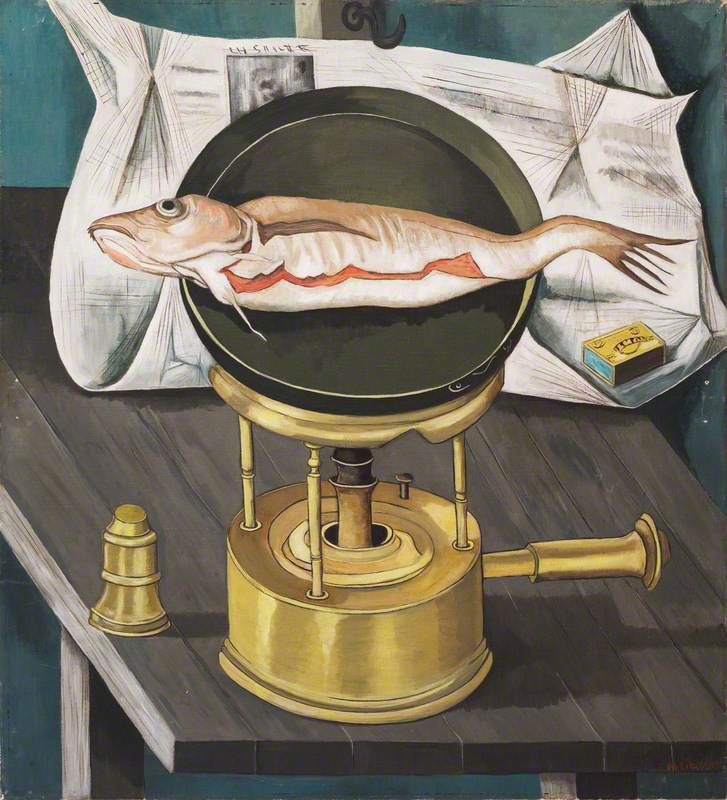

This can be perceived in the paintings she made of mushrooms on a red tablecloth, and a pile of verdant green leeks, in addition to the curious Haddock (1955), which is owned by The Women's Art Collection.

Despite the messy reality of gutting and cooking a whole fish, Panting's canvas is far more clinical and sanitised, with the arrangement of the beady-eyed, oversized fish arranged on the clean frying pan and polished gas burner perhaps having more in common with the language of surrealism and the uncanny.

In addition to these more conventional works on canvas, 'Life is Still Life' also features photography, video, and ceramics. Maisie Cousins' lurid and visceral photographs muddy the boundaries between seduction and disgust, encouraging the viewer to feel simultaneously attracted and repulsed. Glistening egg yolks and half-chewed cherry stones are combined with fresh flowers in Breakfast (2017), unsettling the traditional expectations of a still life image as focusing on something evergreen or flawless.

Breakfast

2017, photograph by Maisie Cousins (b.1992)

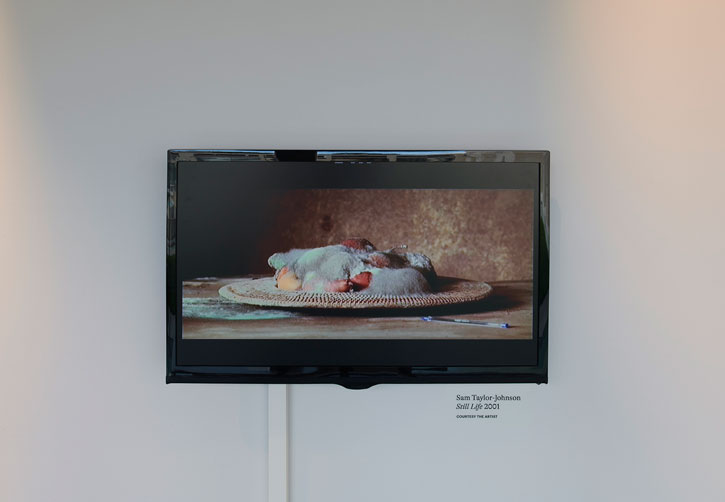

In Sam Taylor-Johnson's silent time-lapse video Still Life (2001), a pile of fruit arranged decoratively on a platter is shown decomposing into a rotting mass of dusty grey mould. The video replicates the Northern European 'vanitas' trend, where images of decaying fruit and foodstuff were set to sombrely impose the transience of life, the futility of pleasure and the certainty of death onto the viewer.

'Life is Still Life' at The Women's Art Collection

Katy Stubbs' ceramic sculpture There Has Been a Terrible Accident (2022) was commissioned for the exhibition. The work takes the form of a decapitated budgerigar, with its bloody head and body lying in an open cardboard box. Here, Stubbs subverts the moralistic tone of the melancholic vanitas image in favour of something more playful and sardonic. 'I like to explore the really dark side of human nature,' she told the New York Times, 'but to make it light'.

A Hint of Blue 2

2021, photograph by Sekai Machache (b.1989)

Sekai Machache's digital photograph A Hint of Blue (2021) disrupts the conventions of the still life genre even further, by converging it with the self-portrait. Standing at a laid table, interacting with the tableware, candles, and food on show, she physically inserts herself into the image, rather than just through metonymic objects.

Philomena Epps, writer

'Life Is Still Life' at The Women's Art Collection, Murray Edwards College, University of Cambridge runs until 12th February 2023