Vanessa who? I hear you say. Name not ringing any bells? Well, fear not because Dulwich Picture Gallery's latest exhibition features six glorious rooms of her paintings that are set to reveal this underrated and underappreciated artist.

Bell was the older sister of Virginia Woolf (you know, that famous feminist writer of the early twentieth century?). She was brought up under a very controlling and patriarchal father who, whilst loved, was also resented by his daughters due to his strict rules and adherence to 'tradition' that dominated their home. His death in 1904 released Bell from the confines of late Victorian sensibilities and she blossomed into a revolutionary, rule-breaking artist. If that doesn't whet your appetite then you should know that this exhibition is Bell's first retrospective ever in the UK and includes many paintings from private collections that have rarely been seen in public. Tempted? You should be.

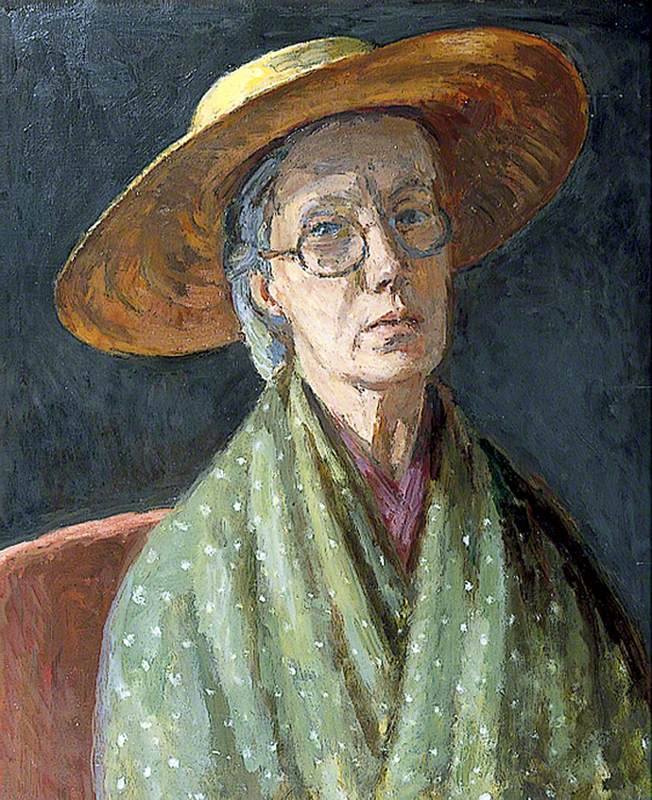

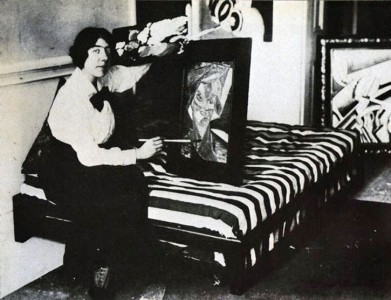

When you glimpse Bell in a photograph, it is difficult to think that she was the rebel I describe to you. Her beautiful, elegant face with elongated features scowls out at you, for she was known to dislike her photo being taken, and she looks quite sulky and vacant. But do not be fooled, dear reader – there is far more to her than meets the eye.

We are introduced to Bell as a quiet force of nature. She is described as radically unconventional yet also possessing a constant stillness amidst the whirring artistic environment that she called home. She belonged to the footloose and fancy-free artistic company known as the Bloomsbury Group. Think born again bohemians. Some of the most renowned artists, writers, poets and critics of the twentieth century were a part of this artistic clan, living (and loving) together as one large family, sharing everything.

In room one we are presented with what appear to be works by two different artists. On one side of the room hang a number of small, muted paintings that reveal Bell's training in the Royal Academy under John Singer Sargent. The colours are dark and the subjects traditional – and not terribly engaging.

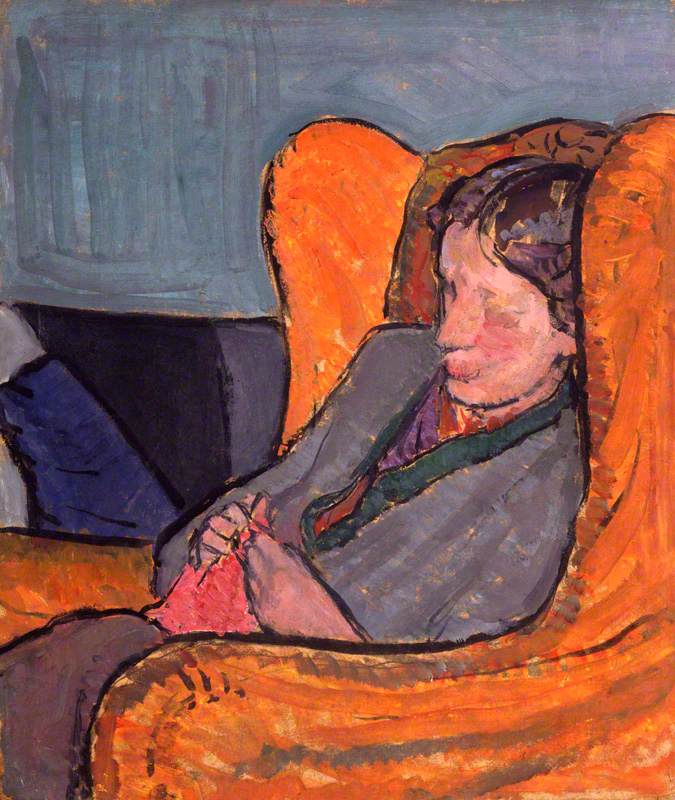

But then we are greeted by three striking canvases on the back wall. Can this be the same Vanessa Bell? Bright colours have been boldly applied and vigorous brushwork has been worked onto the canvas resulting in large, dynamic portraits. They are not stilted, posed and wooden but captured in a moment – a glance to the right or gazing off into the distance.

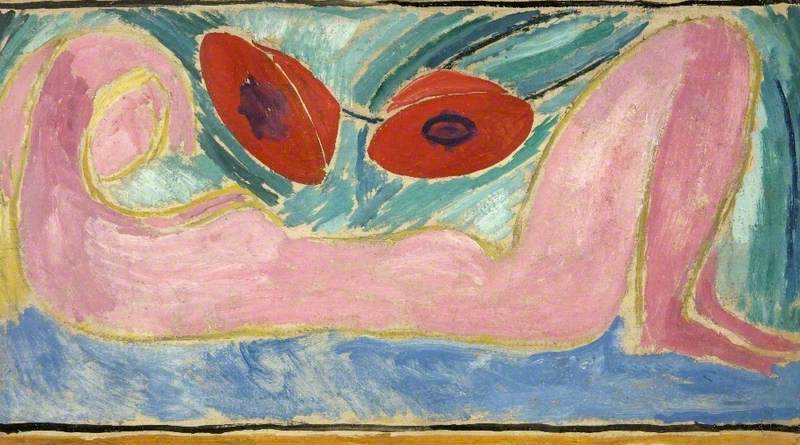

This change was in part due to the death of her parents, which allowed Bell's artistic creativity to flourish. But she was also inspired by Matisse and Gauguin whose work she saw in the Post-Impressionist exhibitions, curated by her friend Roger Fry in London in 1910 and 1912. What is particularly fascinating about Bell is learning how her paintings were louder than the artist herself, who reputedly said 'the best weapon against her father was silence'. It would appear that this was a weapon she used throughout her life, and spoke through bright colour and bold paint.

The portrait of Mrs St John Hutchinson, for example, suggests Bell was not as complaisant as she seemed. Mrs Hutchinson was a known beauty of the day and mistress to Vanessa's husband, Clive Bell. Given the bohemian nature of the Bloomsbury Group, an open marriage was not unusual. They all socialised together as one large company – wives, mistresses, husbands and lovers. The portrait, however, is not particularly flattering. Mrs Hutchinson wears an alarming shade of lime green and looks as if she is sucking on sour grapes. Is this Bell cleverly stating her dislike for the lady whilst also complying with an open marriage?

We see a similar situation arise again with her portrait of David 'Bunny' Garnett, who was known to be a lover of Duncan Grant, a great friend and romantic attachment of Bell's. Both Vanessa and her husband Clive painted Garnett's portrait side by side. Clive's painting shows a charming young boy. Vanessa, however, to quote the co-curator Ian Dejardin, has painted 'Little Miss Piggy' – a boy with flushed cheeks, a sickly complexion and beady eyes. Perhaps she was not such a fan of Bunny as everyone else? The saying 'a picture paints a thousand words' comes to mind...

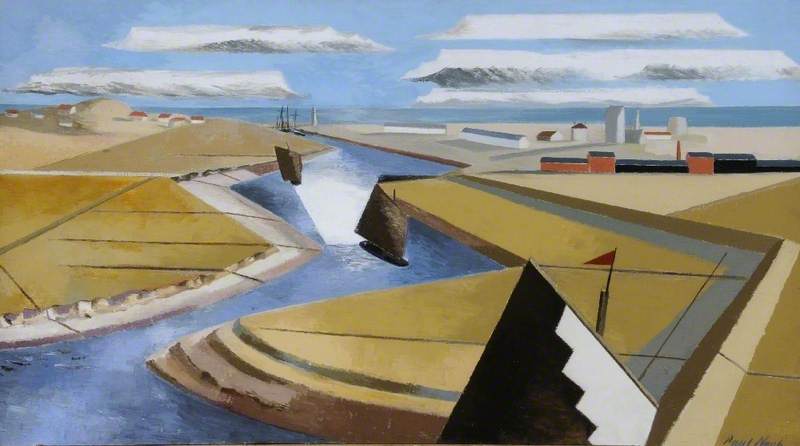

We step into room two and are hit again with Bell's creative experimentation and artistic versatility. As a part of the Omega Workshops, she produced colourful, geometric patterns for new, radical textiles, pottery, rugs and home furnishings. She took these elements of design into her exploration of abstraction in painting, combining her training at the Royal Academy with her interest in design to mould exciting, well-constructed compositions.

You would be fooled when you step into room three that Bell returned to 'traditional painting' when you are met with a series of still lifes. But if you look again, the pots and vases aren't straight but crooked, the flowers sing out rather too brightly against their muted backdrops and lemons and gourds bulge and bloom with flesh-like qualities. Here, Bell's love of life and pleasure comes through together with her fascination with colour and local craftsmanship. She wasn't so much as a 'flower painter' as a disciple of colour, studying the plants in a domestic environment, highlighting how her art was as ingrained in her home life as it was in her career.

Passing through rooms with collections of bright landscapes and intimate domestic scenes, you arrive in the final room which is the cherry on the cake. Here we see how Bell rejected the conventional representation of women and ideals of female beauty. We are met with a company of women who are presented not in a late Victorian 'ready-set-go-mind-the-flash' sort of way but more a 'candid camera' snapshot. There is a fascinating and unusual small Madonna and Child sculpture from Bell's home, Charleston, where Bell has reinterpreted the iconographic canon of this maternal icon. These works recall elements of the first three portraits in room one, and it is a lovely bookend to the exhibition to see how Bell applied her artistic insight specifically to portraits of the 'fairer sex'.

It is clear that Bell was not your 'average gal' and whilst this exhibition contains strong examples of the range of her work, it is in her portraits where she really excels. Dejardin has said that Bell was a remarkable painter who chose relatively unremarkable subjects. So when this remarkable painter chose to paint remarkable people, such as the sensitive portraits of her sister, the end result is fascinating. Being Woolf's sister, it would seem that Bell was sort of the 'Other Boleyn Girl' of the twentieth century, but it is clear she was so much more.

This unassuming, artistic rule-breaker, mother, sister, creative force – call her what you will, is back. And quite rightly too. Let's see that she stays.

Ellie Walker, blogger of View from the Gallery, currently works in sales and marketing with an Art History cultural courses company

'Vanessa Bell (1887–1961)' was on until 4th June 2017 at Dulwich Picture Gallery, London