'Everyone has a crayon in his hand,' wrote the French art theorist Étienne La Font de Saint-Yenne in 1746, reviewing the paintings then on display at the Louvre's Salon, the biannual art exhibition that represented the peak of Parisian taste. 'As with all that is fashionable, the public has embraced it with a frenzy.'

'Crayon' painting – or pastel, as we term it today – was indeed sweeping eighteenth-century Europe. A new technology, pastel accorded well with the artistic preoccupations and priorities of the period. It also appealed to eighteenth-century artists with a zest for experimentation.

Pastels are artificially constructed sticks comprising pigments, fillers and binders, which are rolled and shaped before being left to dry. From the late seventeenth century, it had become progressively easier to create useable sets of crayons for the commercial market, partly as a result of the development of artificial pigments (the first modern synthetic colour, Prussian blue, was developed in 1709).

Pictures in pastel were typically executed on vellum or paper, sometimes mounted onto a canvas stretcher. For this reason, finished works often occupy a strange in-between place between painting and drawing – and pastel's acolytes would argue they share the advantages of each.

Like paintings, pastels are brightly coloured, and can be brought to a high degree of finish. However, like drawings, work can be picked up and put down as the mood, or circumstances dictate. This last point made pastel a popular medium for eighteenth-century amateurs, and those artists (particularly women) who had conflicting demands on their time – women like Rhoda Astley, who was painted by Arthur Pond using her pastels in the 1750s.

At the same time, pastel was also popular with sitters, since pictures could be produced quickly. As a result, pastels were well suited to portraiture: increasingly a boom industry during this period.

Image credit: National Portrait Gallery, London

Rhoda Astley, née Delaval c.1750

Arthur Pond (1701–1758) (attributed to)

National Portrait Gallery, LondonIt was, in fact, a woman portraitist who is generally credited with popularising pastel. Born in Venice into a middle-class family, Rosalba Carriera began using pastel around 1708. By the time she died, she was not only one of the most successful women artists ever to have lived, but one of the eighteenth century's most commercially successful artists of any gender.

Venice was a popular destination for tourists, particularly young British aristocrats on their 'Grand Tour' of Europe. Working in pastel allowed Carriera to maximise her earning potential, by producing portraits quickly for clients who had no appetite for long sittings.

In 1730, Carriera painted the 21 year-old Gustavus Hamilton, 2nd Viscount Boyne, in the black cape, tricorn hat and white mask associated with the 'buata' costume worn at the Venetian carnival.

Image credit: The Henry Barber Trust, The Barber Institute of Fine Arts, University of Birmingham

Gustavus Hamilton (1710–1746), 2nd Viscount Boyne 1730–1731

Rosalba Giovanna Carriera (1673–1757)

The Barber Institute of Fine ArtsThe portrait is a spectacular example of Carriera's economy: the sitter's cloak and veil are almost entirely made up of unalloyed black pigment, the details of the costume being suggested by only a few strategically selected areas, such as the hint of brocade or the dazzling white edging on the hat.

Liberal use of the stump – a small roll of paper used to smooth the pastel's surface – gives the picture a distinctive soft-focus haze. For the sitter, this portrait would have been a souvenir of two key Venetian attractions: the carnival, and Carriera, whose pastels were not known for their likenesses, but rather their aura of distinctly Italian glamour.

Carriera made a triumphant visit to Paris in 1720–21, bringing pastel to the cultural capital of Europe. She arrived only shortly after the young French artist Maurice Quentin de la Tour, who, by the middle of the century, had come to dominate the Salon, exhibiting regularly from 1737 until his retirement in the 1780s.

La Tour worked solely in pastel, and solely on portraits, and his pictures of the French aristocracy and intellectual elite (as well as many members of the middle classes) were characterised by an immediacy and a naturalness that was almost entirely new in art of the period.

His portrait of Henry Dawkins, MP for Southampton, is an unusual example of an English sitter, but it retains all the hallmarks of his style: Dawkins looks directly at the viewer, with just a hint of a smile, the colour on his lips picked up by the light flush on his cheeks. There is nothing in the background to distract our attention from what feels like a direct communion with a real person – though Dawkins's elaborately brocaded waistcoat and the sheen on his velvet coat are rendered with a panache that suggests the speed at which this pastellist was able to work.

In contrast to Carriera and La Tour, who established artistic dominance in Venice and Paris respectively, the Swiss painter Jean-Étienne Liotard hardly ever stopped travelling. Born in Geneva, where he is assumed to have trained as an enamellist, he was an early European visitor to Constantinople, the capital of the former Ottoman Empire and a source of Orientalist fascination for many. Though he most frequently worked in pastel, Liotard also explored oil paint, mezzotint, coloured chalks and miniatures, and produced intricate coloured drawings.

His portrait of Harriet Churchill, wife of Sir Everard Fawkener, the English ambassador to Constantinople (Istanbul today), exemplifies his attention to surface texture and meticulous rendering of detail, both qualities well suited to pastels.

Composed of millions of tiny particles, which never fully dry, pastel pictures reflect light in many directions at once, giving them a distinctively velvety texture. Their colours are also particularly vibrant, and in this respect Liotard consistently pushed the potential of the medium, often painting the reverse of his supports with solid blocks of contrasting or complementary colour, to intensify their luminosity.

When Liotard visited England in 1753, he aroused the scorn of the ambitious oil painter Joshua Reynolds, but by the end of the century, Britain had its own industry of pastellists, and several treatises on the medium, notably John Russell's 1772 Elements of Painting with Crayons. Russell studied the example of Carriera, and, like her, blended his strokes to create a hazy atmosphere. He also shared Liotard's interest in colour.

'The beauty of a Crayon Picture,' he wrote, 'consists in one colour shewing itself through, or rather between another.' This is exemplified in the rich blues of his representation of the teenage James Lawrell.

Lawrell left Eton in 1799, and this picture is part of a collection of portraits of favoured Eton graduates, traditionally requested from selected students in lieu of the school's leaving fee. The fact that Russell was selected to paint the portrait may in itself indicate pastel's increased status by the end of the century. Previous portraitists selected for the task had included Reynolds, Thomas Gainsborough and George Romney, and – far from being shut in a portfolio – Russell's pastel would have been expected to hold its own on the wall beside them.

For many of Russell's contemporaries, pastels were a practical choice. The oil painter Ozias Humphry picked up the medium because he found it easier to use after suffering an injury to his eyes. By 1792, he had been appointed Portrait Painter in Crayons to the King (George III). Humphry's portrait of Christiaan van Molhoop, the so-called 'running footman' of the Dutch ambassador Baron van Nagell van Ampsen, was part of a series of portraits of the Dutch court.

It has pastel's typical brilliancy, with particular care lavished on the flamboyant costume, in the colours of the Dutch flag (footmen like van Molhoop were often elaborately dressed, since their role was inherently public).

However, the portrait lacks some of the refinement of earlier pastels, such as those of Carriera and Liotard: many of the lines remain visible, while the area around the head highlights pastel's problematic side. This may be a reworking that has not been fully concealed – pastel does not allow for easy changes of mind – or possibly an attempt at using a fixative.

Since pastel particles never fully adhere to their support, they are extremely vulnerable to damage. To counter this, recipes for fixatives (often using fish glue) increasingly began to percolate through European art circles in the later eighteenth century – in many cases ultimately resulting in the partial, or total destruction, of the very pictures artists had been hoping to preserve.

Though pastel portraiture dipped in popularity across Europe in the early nineteenth century, many British artists continued to find the medium useful, particularly when producing works that straddled the divide between the finish typically expected of oil paint, and the more experimental paper preparatory study.

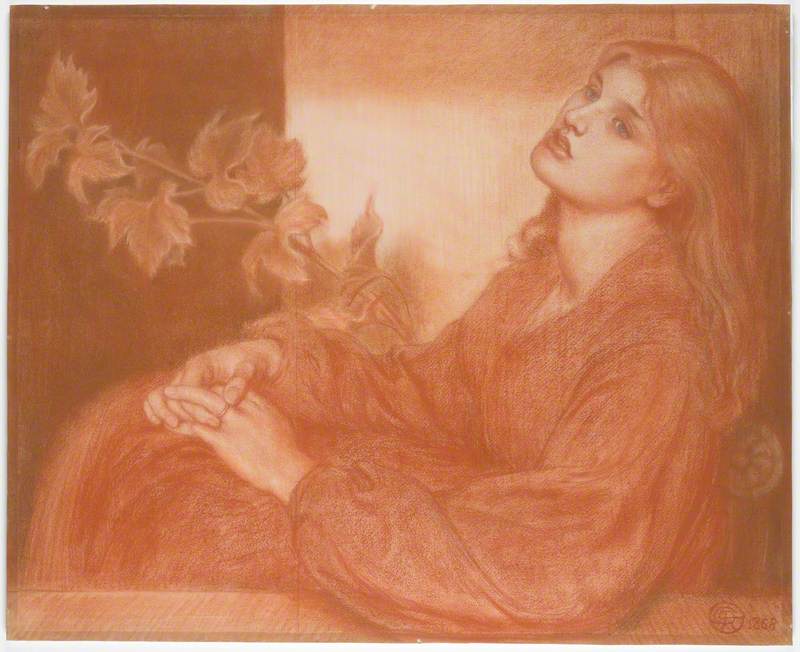

The Pre-Raphaelite painter Edward Burne-Jones, famous for drawing almost obsessively, often used pastel in combination with watercolour and gouache (powdered pastel pigments mixed with water) to test how sketches might work as paintings, and to explore their possible colour and tonality.

Working with pastel allowed him to produce more finished work than he would have been able to execute in watercolour alone, thus enabling him to develop themes and ideas over a greater number of pieces – as with the series of works on the story of Cupid and Psyche, a subject to which he returned seventy times over the course of thirty years.

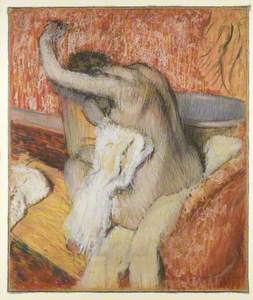

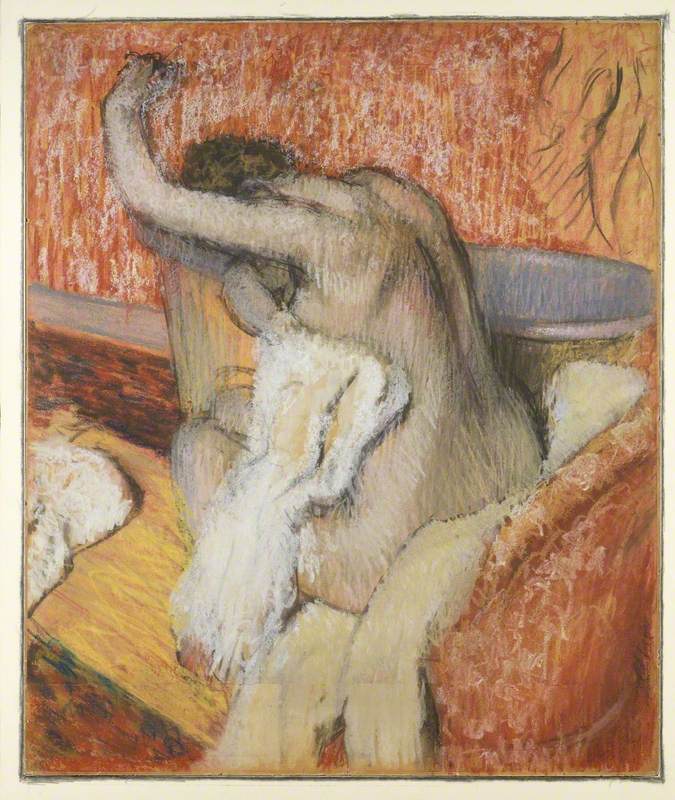

Unlike in Britain, pastel in France suffered a precipitous decline in the early nineteenth century, increasingly considered an unserious art form inappropriate for the large-scale ambitions of the post-Revolutionary world. Only in the 1860s did French artists really return to the medium, and many of this generation had made a careful study of eighteenth-century art and techniques. Chief among them was Edgar Degas, who produced well over 500 pastels between 1880 and his death in 1917.

Typical of his later series showing women bathing or drying themselves, After the Bath is composed of distinct layers of colour, which are left unblended, giving his work a rhythmic quality and extraordinary chromatic richness.

After the Bath – Woman Drying Herself c.1895

Edgar Degas (1834–1917)

The Courtauld, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust)Degas often used pastel in powdered as well as wet form, occasionally mixed it with steam, and combined it with other media such as monotype prints, tempera and oil, to create a huge range of tonal values. Justly celebrated as a master of the medium, Degas showed what pastel could be – but in doing so, he joined an illustrious line of pastellists going back two centuries, always relentless in their desire to explore the full possibilities of this distinctively charismatic medium.

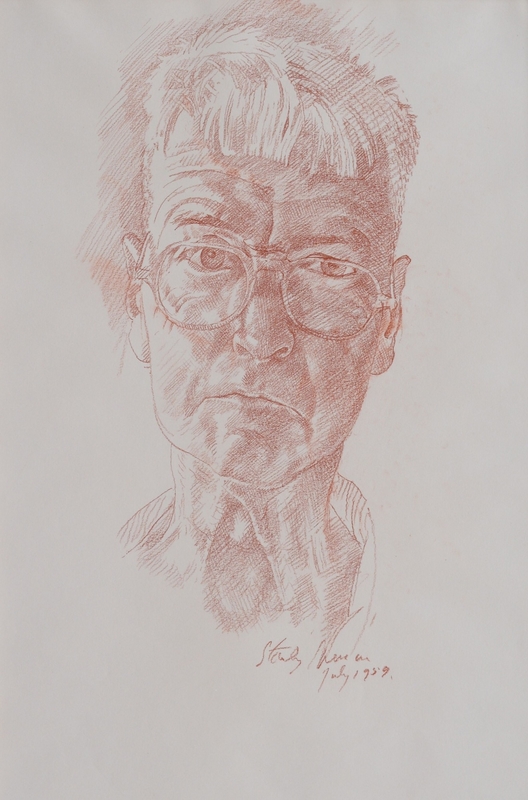

© courtesy of the artist and Thaddaeus Ropac, London. Image credit: Arts Council Collection, Southbank Centre, London. Image courtesy of the artist and Thaddaeus Ropac, London

lick your teeth, they so clutch 2021

Rachel Jones (b.1991)

Arts Council Collection, Southbank CentreThat exploration continues to this day – artists including Rachel Jones, Claudette Johnson and Paula Rego have all used pastel in their contemporary works.

Kirsten Tambling, art historian

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation

Further reading

Christopher Baker, Liotard: A Portrait of Eighteenth-century Europe, Unicorn, 2023

Thea Burns, The Invention of Pastel Painting, Archetype Publications, 2007

Neil Jeffares, Pastel & Pastellists

Angela Oberer, Rosalba Carriera (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2023

John Russell, Elements of Painting with Crayons, printed for J. Wilkie and J. Walter, 1772

Marjorie Shelley, 'Painting in the Dry Manner: The Flourishing of Pastel in Eighteenth-century Europe', The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, 68:4, 'Pastel Portraits: Images of 18th-century Europe', 2011, pp.4–56