Rugby union has long been termed 'the game they play in heaven'. Its ideals of mutual respect and fairness, its indefatigable spirit and its ability to fashion a camaraderie transcending the field are just some of the reasons cited for this lofty status. But if one nation demonstrates a devotion to the game that replicates heaven on Earth, then arguably that nation is Wales.

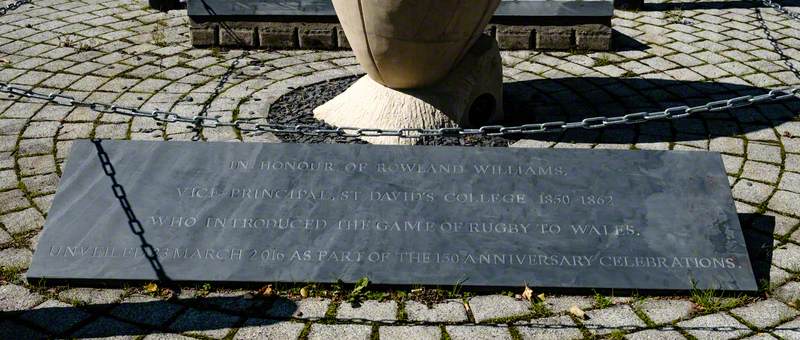

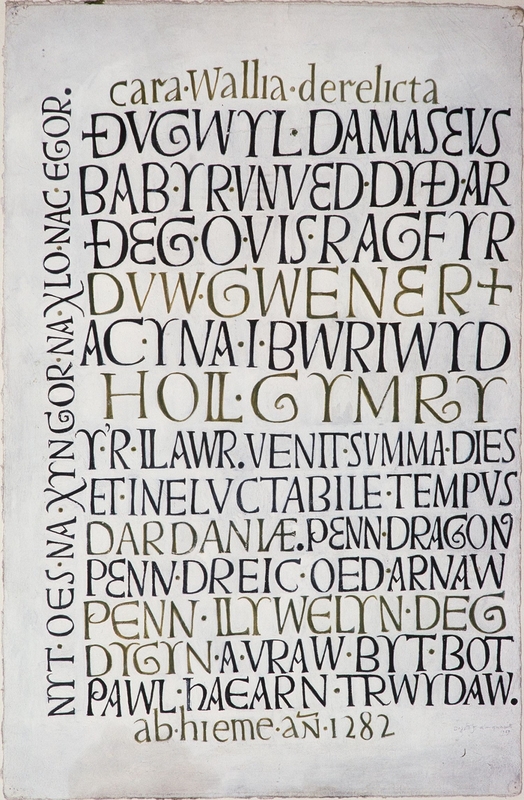

Since the game's arrival in 'The Land of Our Fathers' in the 1850s – when Rowland Williams first brought the sport from Cambridge University to St David's College, Lampeter – rugby union has inextricably stitched itself to Wales's national consciousness, permeating its art, literature, music, film and even its religions.

In 1905, when commenting on a rendition of Hen Wlad Fy Nhadau before an international at Cardiff Arms Park – the first time a national anthem was sung ahead of kick-off to a sporting event anywhere in the world – one New Zealand newspaper likened it to a spiritual experience for its capacity to bring a 'semi-religious' feel to the contest.

Perhaps it was the memory of these heady days when Wales first beat the mighty All Blacks – which happened to coincide with a great religious revival – that made songs like Cwm Rhondda (Rhondda Valley) with its stirring call to 'feed me till I want no more' commonplace in the stands and terraces of Cardiff through the golden era of the 1970s. Or maybe it was the byproduct of a collective identity forged in the coal mines, iron works and non-conformist chapels during the rapid industrialisation from the 1850s onwards? Both explanations have merit. As world-renowned Llanelli and British and Irish Lions coach Carwyn James remarked, 'a nation's memory is its history.'

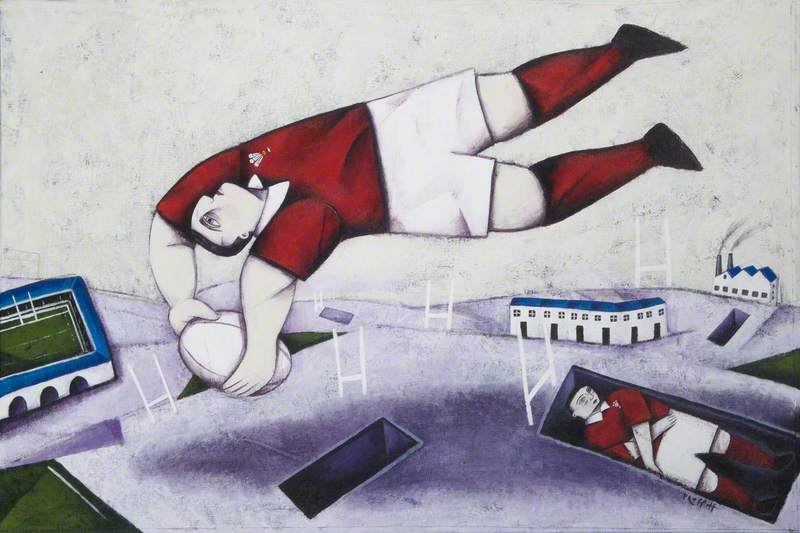

Paine Proffitt's striking All Welsh Rugby Players Go to Heaven illustrates this in many ways. Here, the central figure, floating through the air in the famous scarlet jersey, white shorts and immaculate socks is presented as a demi-god, reflecting a privileged position – a sort of abstract immortality afforded to players beyond the grave.

The reverence heaped on Welsh players for their skill and bravery on the field is implied through the intriguing anatomy of the hero gracing the whitewashed sky. The subtle but supernatural quality of the twist in his hips is at odds with the direction of the lower limbs, his outstretched arms defy any hint of an arch to the spine: movements only possible by sheer genius – or divine intervention!

For me, it conjures historian Dai Smith's view of the Welsh player christened 'The King' by the rugby fraternity: 'Barry (John) played in a different dimension of time and space to other rugby players' – or of J. P. R. Williams: 'My god, he walked on water!' An indication, if ever there was one, that the most accomplished international rugby players in Wales ascended to god-like status.

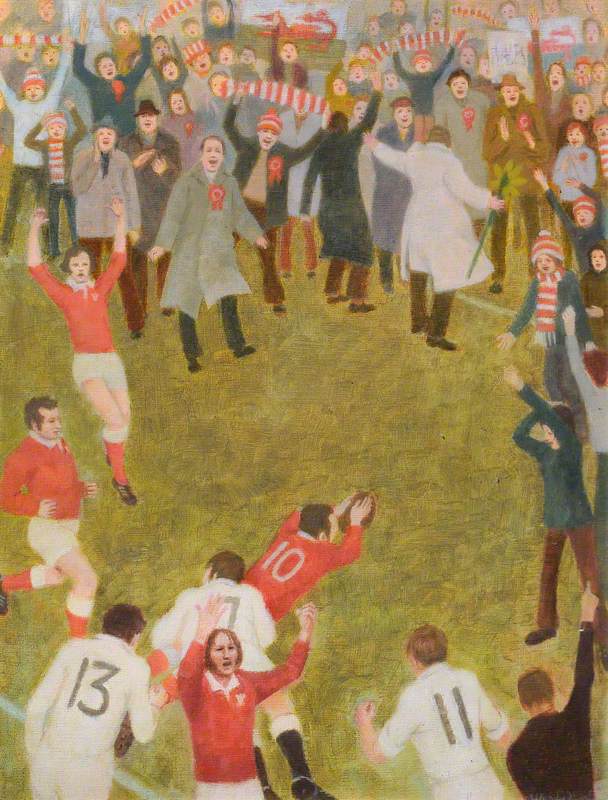

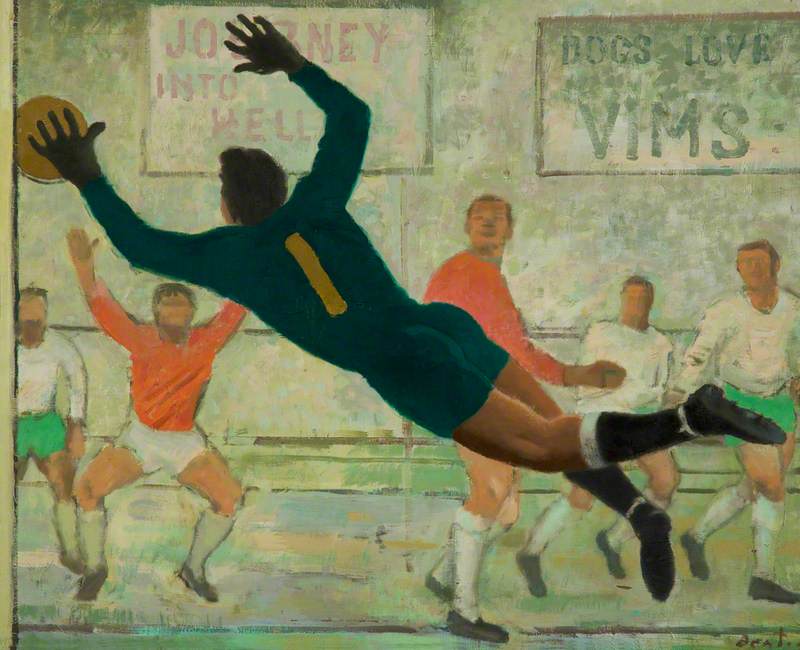

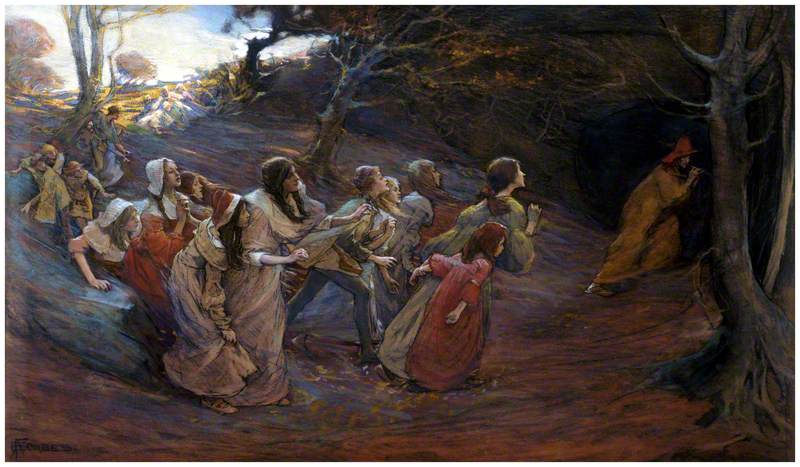

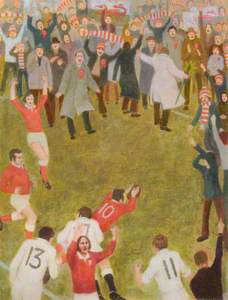

This adulation is reflected in Wendy Noel's delightful Hymns and Arias. The title, which takes its name from Max Boyce's iconic ditty, will be familiar to Welsh rugby supporters and global followers of the game alike. A song that came to be adopted, not only in the stands and terraces of international rugby's great cathedrals, but in pubs and social clubs across the country, especially those at the heart of the old south Wales coalfield. Composed in the mid-1970s, it endures to this day in the hearts and mouths of Welsh rugby's faithful, not to mention fans of Swansea City!

Returning to Proffitt's image, it's important to note the presence of a second player: a figure lying in an open grave, arms crossed, a mere mortal contrasted to the celestial figure above. Crucially, he too is adorned in the iconic red jersey. The artist could be suggesting the close, almost mythical connection that Welsh people – especially in more rural communities – have with landscape; how our modern nation has been shaped by resources extracted from the ground; and the sense that these gods of the sporting arena, born ordinary folk, will also ultimately return to the soil.

However, the rugby-obsessive at my core also likes the romantic notion that representing Wales in rugby is the pinnacle of a life's achievements. In this context, the work can be interpreted as a dreamscape for that almost universal Welsh childhood experience of growing up with the ambition of pulling on that famous red jersey for real.

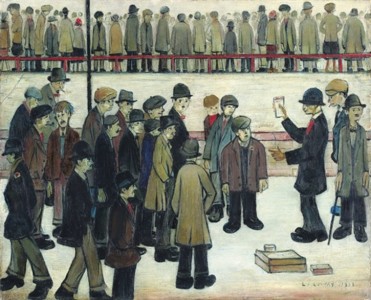

But why is rugby such a fundamental part of Welsh identity? Wales is different to most rugby-playing nations in that rugby was swiftly embraced by people of all social backgrounds and occupations. This is apparent in the attire worn by the partisan pitch invaders in Noel's piece. Across the border in England, rugby union was largely the game of the establishment. The same was true in Ireland and Scotland. In Wales, however, rugby union managed to transcend class and rugby clubs became prominent places at the heart of their communities.

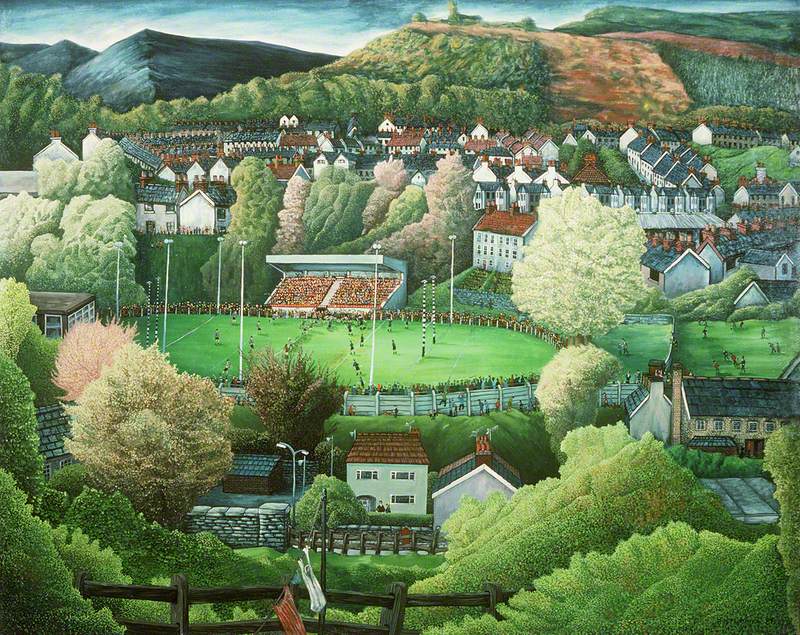

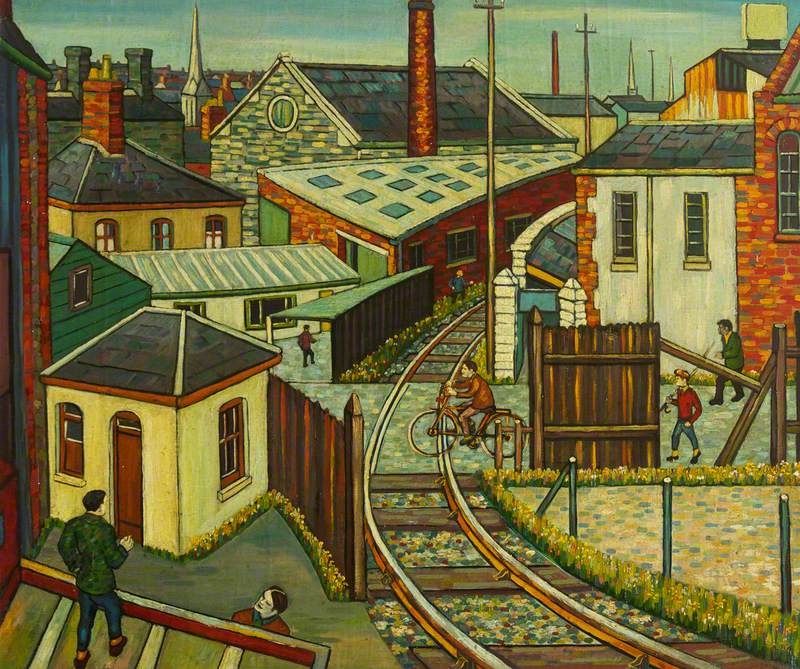

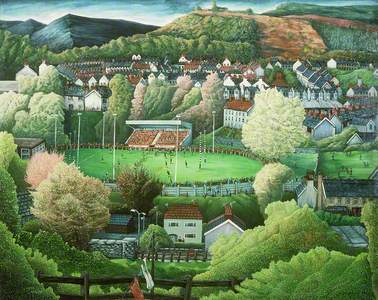

This idea is central to The Rugby Match by Ronald Herbert John Lawrence. The landscape is unmistakably Sardis Road, Pontypridd, with its oval field, black and white striped goalposts, and fabulous setting at the gateway to the Rhondda. While rugby in Wales captured the imagination of people from different social backgrounds, like the tribes of ancient Britain these local communities developed their own distinct identities.

For me, Lawrence's piece captures the essence of working-class life in the old south Wales coalfield: how the landscape shaped the town; its characteristic terraced housing; the nod to its rural past through abundant greenery. But not least, it captures rugby's popularity. The stand and terraces are brimming with supporters. Note the figures climbing the perimeter wall to sneak a peek or gain free entry: a spectacle I remember well from watching my hometown club Maesteg while growing up in the 1980s. This was a time when it felt like an entire community attended a home fixture every other Saturday – a time when every town had local gods, regardless of whether they made it to the national side.

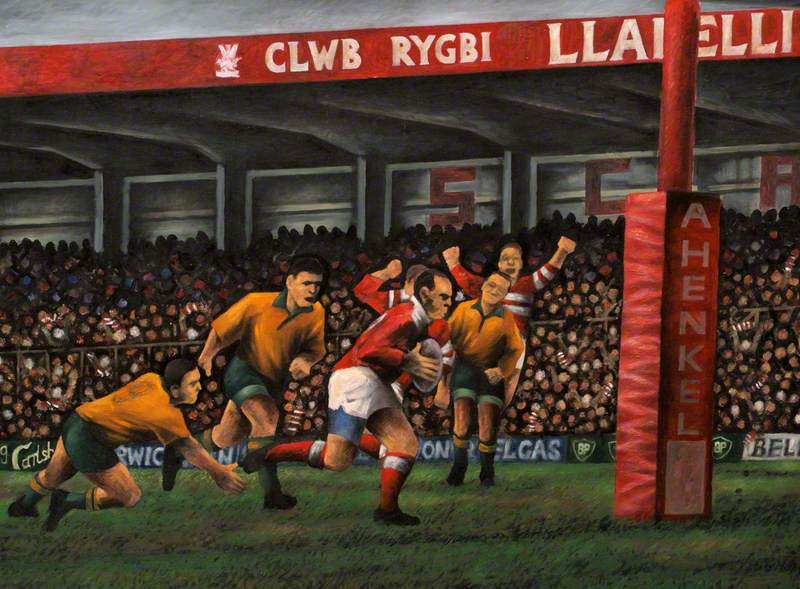

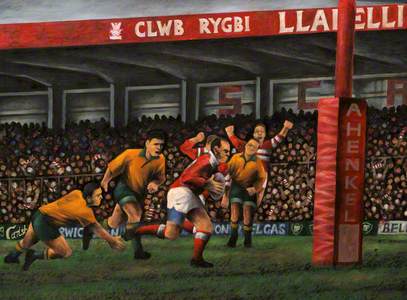

We observe similar scenes with Gareth Davies' Y Clwb Rygbi. In a packed Stradey Park, Colin Stephens jumps for joy as Ieuan Evans goes over for a try against reigning world-champions Australia in 1992: a time when Welsh club rugby was still the envy of the world for the crowds it attracted. Davies's work highlights the prominence of y Gymraeg (the Welsh language), an element of Welsh identity damaged in the south-east by rapid industrialisation, but that remained steadfast further west.

Arguably, this linguistic divergence became a key cultural distinction that fuelled tribal rivalries on the club scene, noticeably when east met west. Even today, language underpins a cultural and geographical difference separating Llandovery from Llantwit Major and Carmarthen Quins from Cardiff Harlequins. And in the professional game, Cymraeg remains an integral part of the Scarlets' identity. In their early years, they adopted that most defiant of Welsh anthems, Dafydd Iwan's Yma o Hyd,(Still Here), long before it became synonymous with Welsh football.

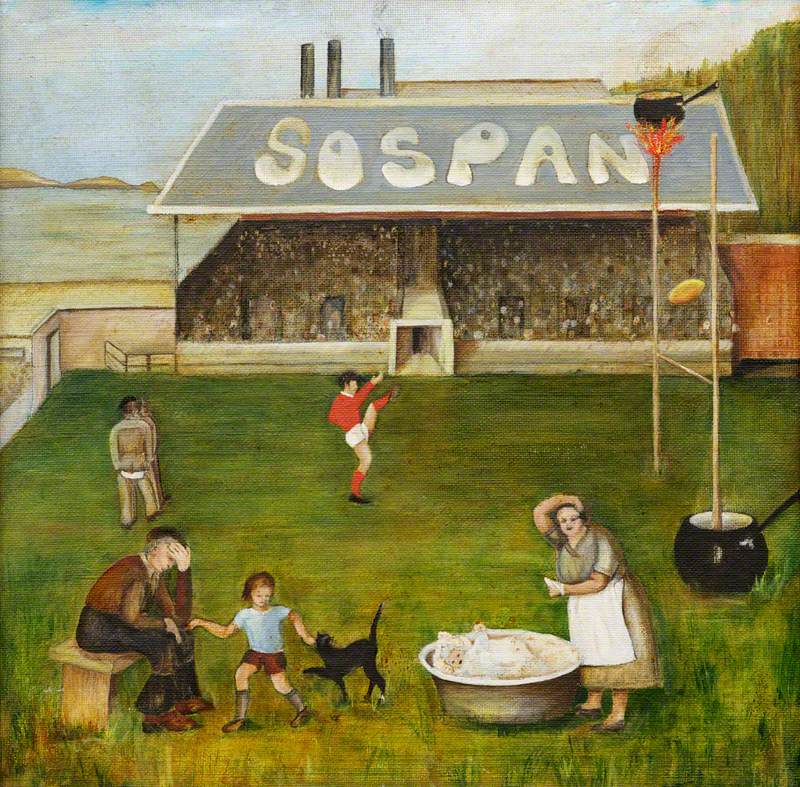

Sosban Fach (Little Saucepan) by E. R. M. Williams - based on the famous Welsh folk song associated with Llanelli RFC - also speaks to the distinction of a more agricultural way of life west of the Loughor Estuary. Yet, it still places industrialisation and a ball-playing hero in red at the centre of its story. And what a story: of tin plate production (the saucepans) and victories over the All Blacks!

Perhaps the last word should go to Gareth Edwards. Like Phil Bennett in his beloved Felinfoel, Ray Gravell in Llanelli, Billy Boston in Tiger Bay, and Max Boyce in Glynneath, Gareth – the legendary scrum-half – has been sculpted into immortality, his statue on display in the heart of Cardiff's shopping district.

In his foreword to The Wales Rugby Miscellany Edwards wrote 'Rugby is part of the DNA of Welshmen and women across the globe. It is at the heart of our very essence, defining us as individuals and as a nation.' And let's face it, there's not a god out there who would refuse this great man entry at the pearly gates. And if they did, I've no doubt he'd hurdle the wall to show the crowd what they are missing!

Leigh Manley, writer, poet and creative facilitator

This content was supported by Welsh Government funding