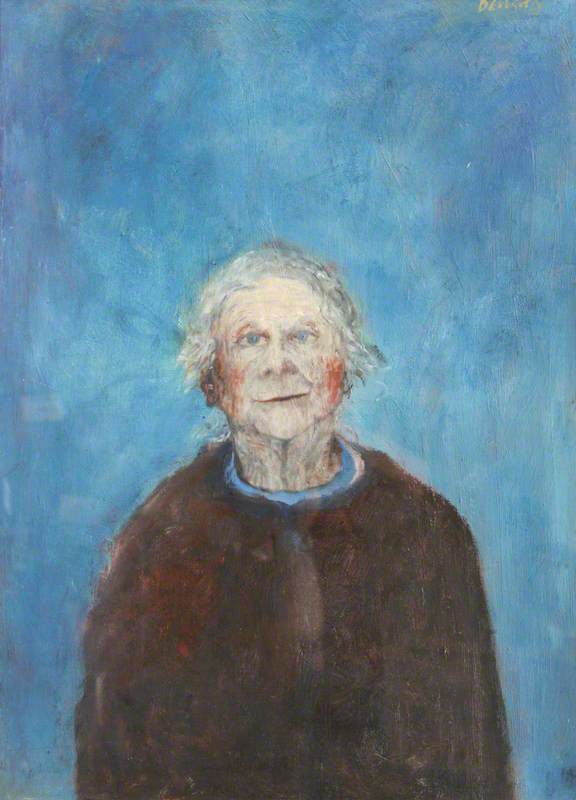

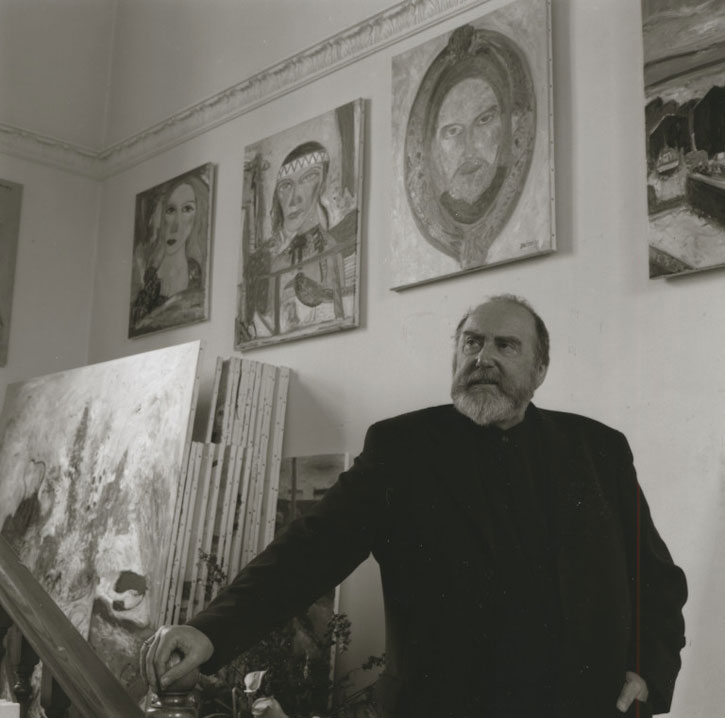

One of the most influential Scottish artists of the post-war period, John Bellany (1942–2013) re-established a native, figurative style at a time when abstract art was in the ascendant.

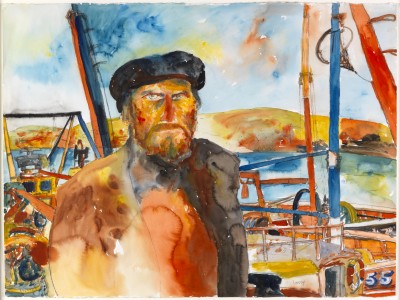

Raised on Scotland's east coast, the sea and the people who worked there remained an inspiration throughout his long career, though as an Expressionist, such subject matter came to hold strong symbolic values.

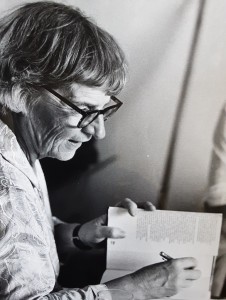

John Bellany RA

May 2000, silver gelatin print photograph by James Hunkin (b.1958)

Bellany was born in 1942 in Port Seton, 10 miles from Edinburgh, into a family of fishermen and boat builders. Within this close-knit community, another formative influence was a strict Calvinist upbringing that provided him with a strong sense of mortality and a visceral sense of good and evil, preoccupations that appeared from his student years, beginning at Edinburgh College of Art (1960–1965).

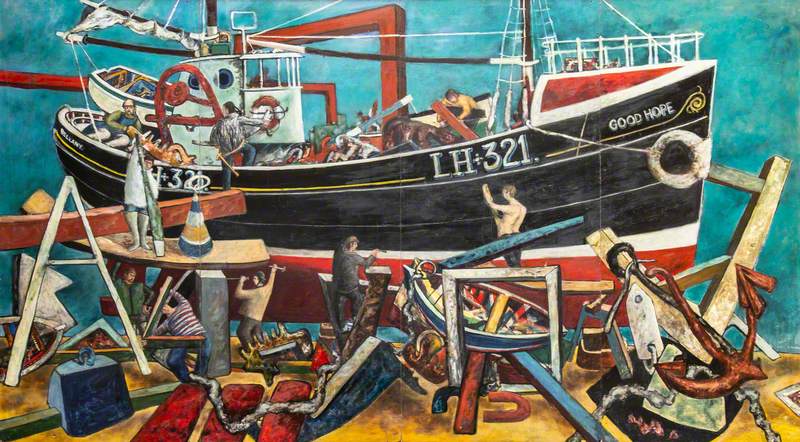

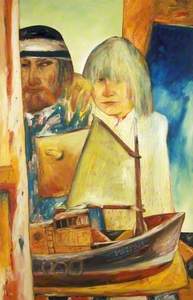

Early canvases, often painted on a monumental scale, were marked by a high degree of ambition and self-confidence. Boat Builders (1962), an oil on board, is almost five metres wide.

Emotive depictions of trawlermen and their precarious existence, such as Fishing Boat (1964), challenged the decorative landscapes and still lifes that characterised much contemporary Scottish painting during that decade.

The social realist heroism of Bellany's early work also ran counter to the prevailing trend for abstraction, revealing instead his admiration for modernist artists such as Fernand Léger whose 1950s series Les Constructeurs was a direct inspiration. Bellany also looked to the Old Masters, among them Tintoretto, Rubens and Poussin.

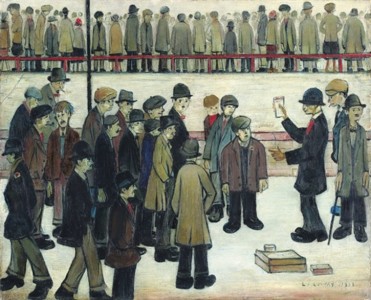

Going against the grain seemed to come naturally to Bellany at this time: for the Edinburgh Festivals of 1964 and '65, the artist and his colleague Sandy Moffat infamously mounted their own outdoor exhibitions, hanging paintings on the railings outside the city's Scottish National Gallery and Royal Scottish Academy.

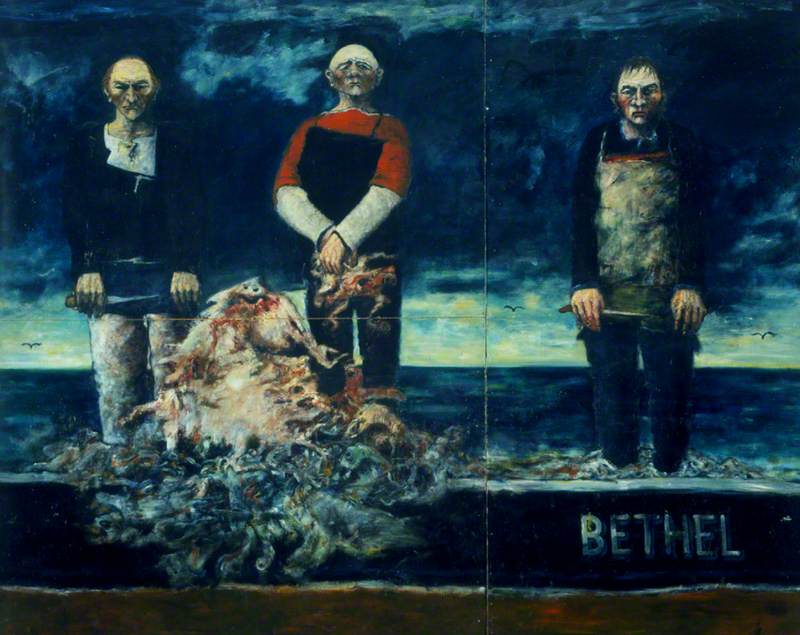

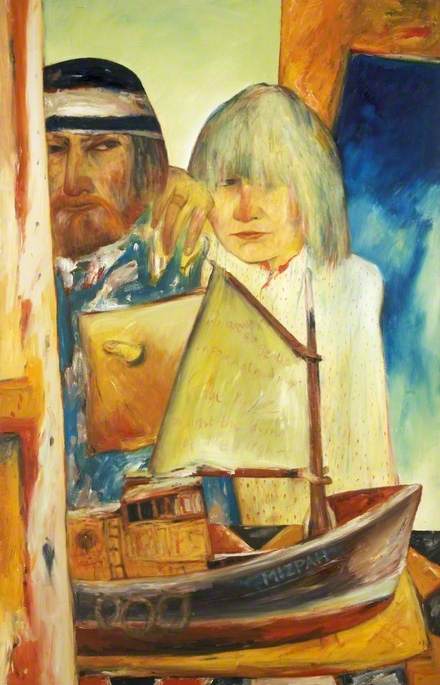

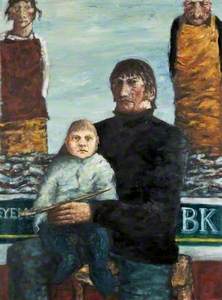

In 1965, Bellany moved to Royal College of Art, London, where his vision and iconography became broader. Kinlochbervie (1966) and Bethel (1967) are filled with symbolism that draws on traditional Christian motifs, such as the Crucifixion and Last Supper.

These elements transform images of ordinary fishermen into powerful allegories, linking Bellany's experiences to Western art's longstanding themes.

These preoccupations took a more dramatic turn following a trip to East Germany in 1967, where Bellany was profoundly moved by a visit to the site of the Buchenwald concentration camp, which encouraged him to introduce darker notes into his work. His worldview began to grow more tragic, ambiguous and complex.

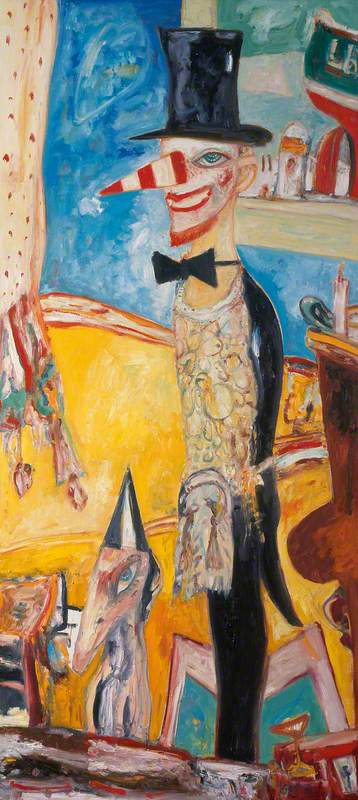

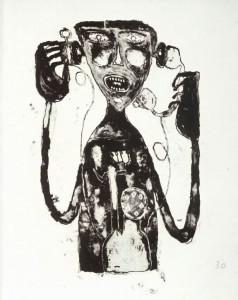

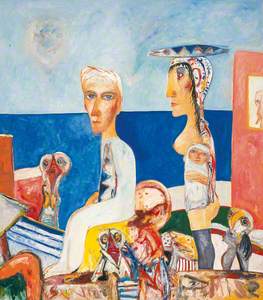

Influenced by the work of the German Expressionist Max Beckmann, he moved into a period where he dealt with the concepts of original sin, sex, guilt and death, as is the case with Lap Dog (1973).

A female figure, her face obscured by a sheep-head mask, representing self-sacrifice, faces a more indistinct male (the artist himself) accompanied by a phallic monkey, with religious symbols of ladder and fish in the background – lust and guilt forever in close contact.

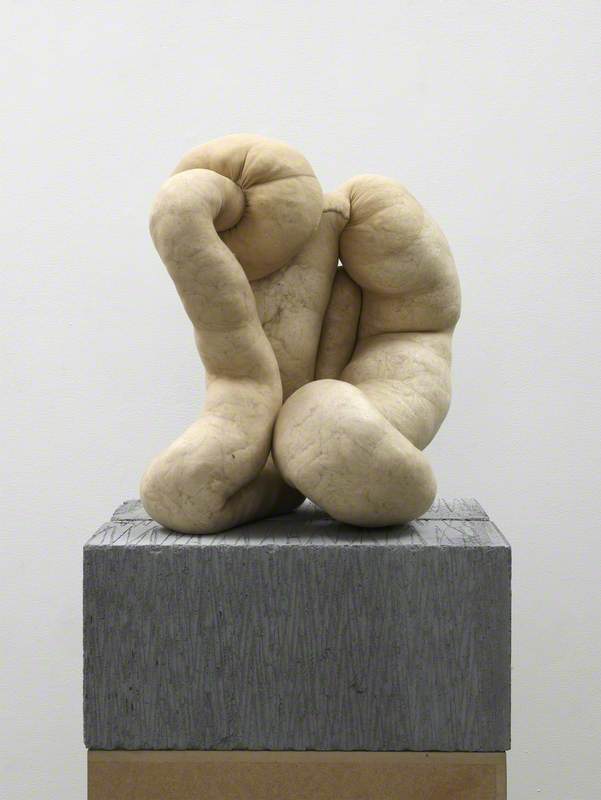

At the same time, Bellany's boat motif came to symbolise the soul's journey, just as his brushwork, in paintings such as The Sea People (1975), became more free and expressionistic, leading to a period of semi-abstract work predominated by themes of aggression, violence and general breakdown.

He also began to develop a complex repertoire of symbolic creatures, including various fish, birds, skeletons, dogs, cats and monkeys. These figures represented the artist or embodied his personal demons.

L'Horloge (1979) is especially enigmatic with its bird heads that suggest first-hand observations of seabirds, alongside awareness of Beckmann's bird-masked figures.

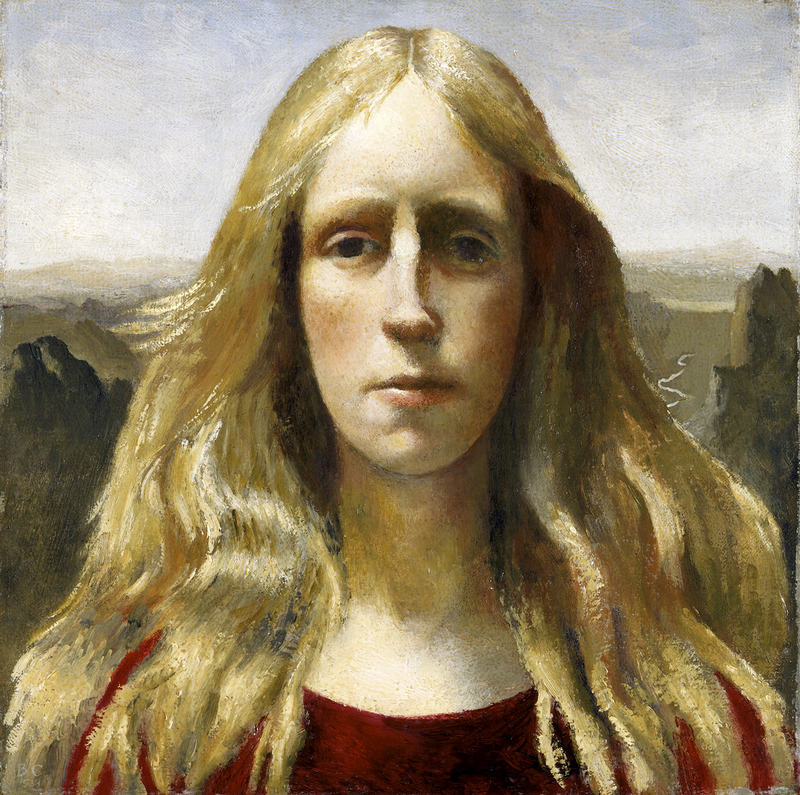

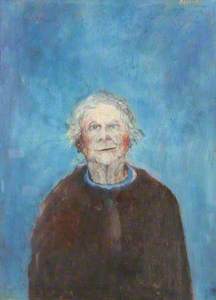

During the late 1970s, this feeling of fate and doom began to be alleviated as Bellany embarked on a new relationship with his second wife Juliet Gray, painting several tender portraits of her.

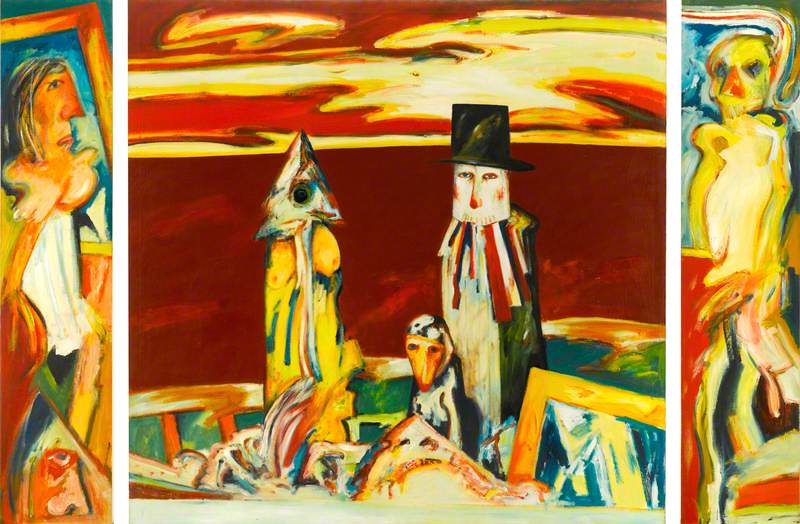

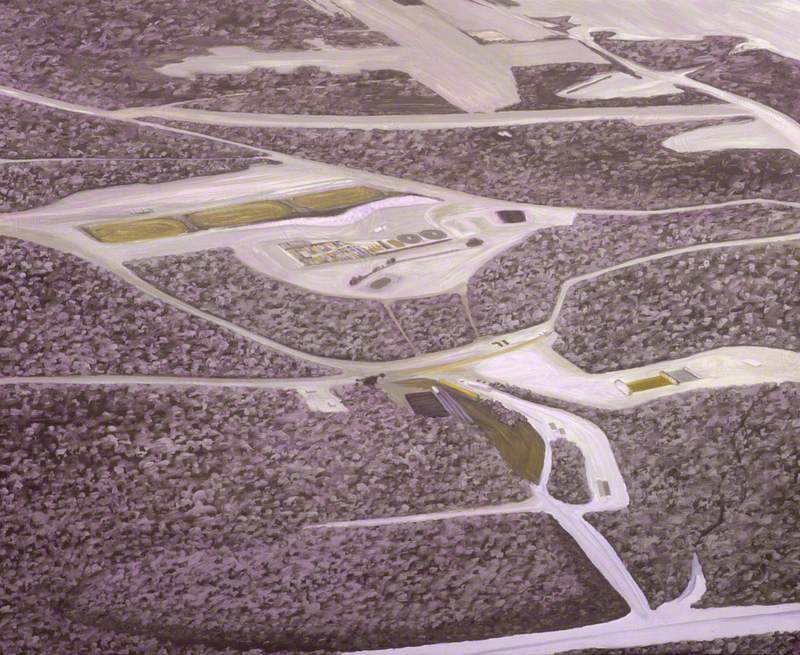

Lune de miel (Towards the Lighthouse)

(triptych, centre panel) 1980

John Bellany (1942–2013)

However, the highly gestural, attacking manner in which he painted pieces such as his triptych Lune de Miel (Towards The Lighthouse) (1980), reflected renewed turbulence in Bellany's life, including Juliet's bouts of depression and his own similar troubles exacerbated by struggles with alcoholism.

His career, in contrast, was going from strength to strength. His first international exhibition came in New York in 1982, with more overseas shows to follow.

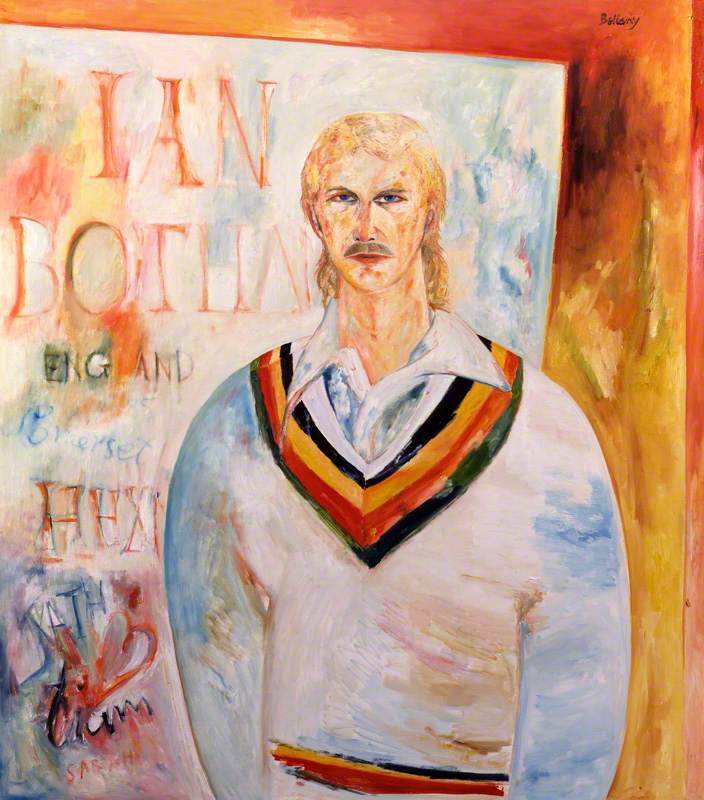

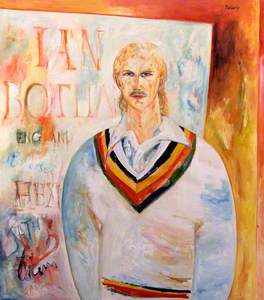

Another landmark came in 1986, a show dedicated to his work at the National Portrait Gallery, London, the institution's first solo exhibition. It centred around Bellany's portrait of the England cricketing hero Sir Ian Botham, a work that the collection had acquired the previous year.

In the mid-1980s, a serious illness and the deaths of both Juliet and his father led Bellany to reconsider his personal life: he reunited with his first wife Helen Percy, marrying her again in 1986.

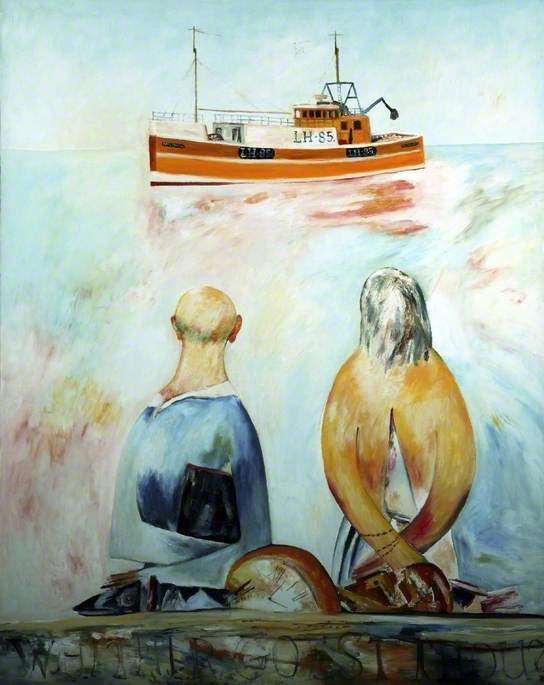

Paintings of this time became marked by reflective calm, characterised by a tighter handling of paint, lightness of touch and a narrow range of warm yellows, oranges and reds, with blues as a contrast. Wither Goest Thou (1986) is imbued with an especially elegiac feel.

By 1987, Bellany had stopped drinking, yet still needed to undergo a life-saving liver transplant. The artist made a near-miraculous recovery from this long and arduous operation at Addenbrooke's Hospital, Cambridge, something his surgeon put down to a desire to carry on working.

Returning to health, Bellany was fired by renewed energy, once again tackling large canvases with ambitious compositions, where he pitted his talents against those of the Old Masters he revered, among them Rembrandt and Titian. Bellany painted the above work in 1991 for an exhibition dedicated to him at The Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, where he had become a frequent visitor.

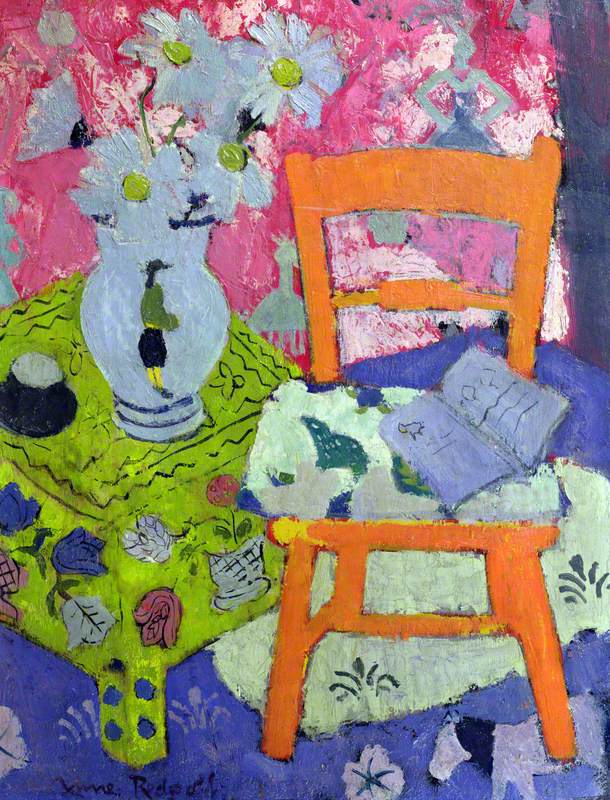

It relates to another work in its collection – Titian's Venus and Cupid with a Lute Player (1555–1565). He also returned to themes he had explored around two decades earlier – the pleasures of earthly delights and the guilty consciousness in the Calvinist imagination, as with the triptych Sweet Promise (c.1994).

Sweet Promise

(triptych, left wing) c.1994

John Bellany (1942–2013)

In 1995 Bellany made a three-month trip to Mexico, where seeing the traditional Day of the Dead celebrations led him to question his Calvinist outlook on life and death. Three years later, he bought a house in Tuscany and began to spend part of the year there. Enjoying the Italian dolce vita reinforced his more life-affirming, optimistic view of the world. Bellany's paintings became brighter and more colourful as his sense of guilt and personal doom was lifted.

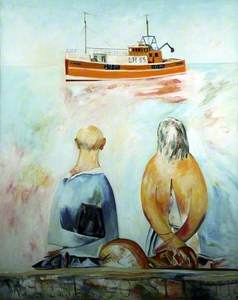

In his final decade, Bellany returned to painting landscapes, townscapes and harbour scenes, inspired by frequent travels abroad, home life in Italy and visits to Scotland.

The ‘Dawn Pearl’ in Port Seton Harbour

before 2006

John Bellany (1942–2013)

He passed away in 2013, just months after a major retrospective at the Scottish National Gallery – the venue he had once picketed with his student work. This was his first show of this scale in three decades, and its title perfectly captured the essence that set him apart as a painter: 'John Bellany: A Passion for Life'.

Chris Mugan, freelance journalist