It was perhaps The Kinks who most neatly defined the customer of the late 1960s London boutique, singing in their 1966 hit 'Dedicated Follower of Fashion': 'His clothes are loud, but never square, it will make or break him so he's got to buy the best, 'cause he's a dedicated follower of fashion...'

Founder of Granny Takes a Trip, Nigel Waymouth, accompanied Michael English and Guy Stevens

1967, photograph by Patrick Ward for 'The Observer'

At this time there was a feverish excitement in and around Chelsea as scions of old-money families and entrepreneurial bohemians opened boutiques to dress their friends from the new countercultural aristocracy of artists, designers and pop musicians. With names like Granny Takes a Trip, Hung On You and Dandie Fashions, these outlets reflected the contemporary preoccupations of hallucinogenic drugs, psychedelic experimentation and the sexual revolution.

An exhibition at the Fashion and Textile Museum, 'Beautiful People: The Boutique in 1960s Counterculture' (until 13th March 2022) explores the vibrant history of 1960s boutique designs, which sparked a fashion revolution.

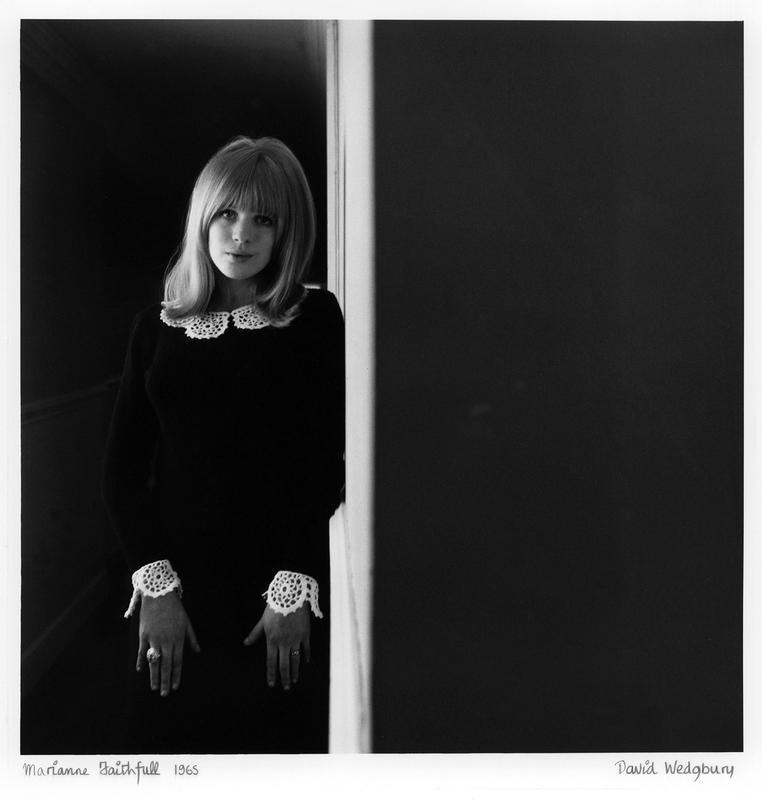

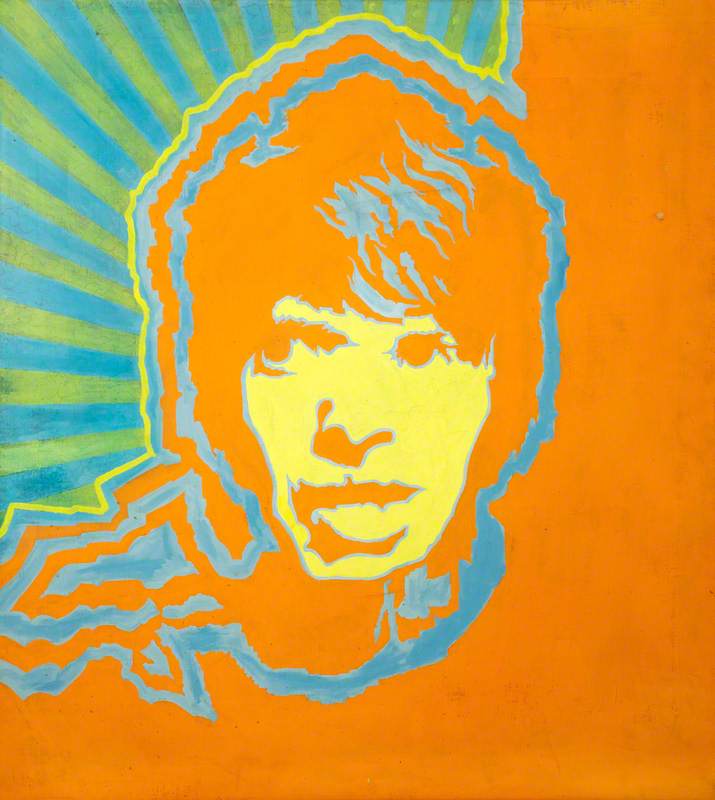

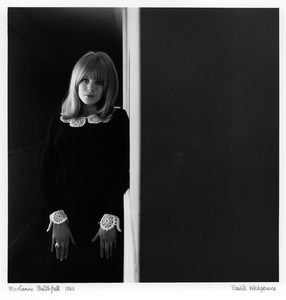

The 'beautiful people', a term coined by Vogue editor Diana Vreeland, was applied to celebrities such as Mick Jagger, Marianne Faithfull, Patti Boyd, Terence Stamp, Jimi Hendrix and The Beatles, all of whom beat a path to the dusky, patchouli-scented interiors of boutique emporia to buy androgynous and flamboyant garments in crepe, chiffon, satin and velvet. Although boutique fashion was deeply embedded in the new counterculture it also looked to art of the past to bring about a modern 'Peacock Revolution'.

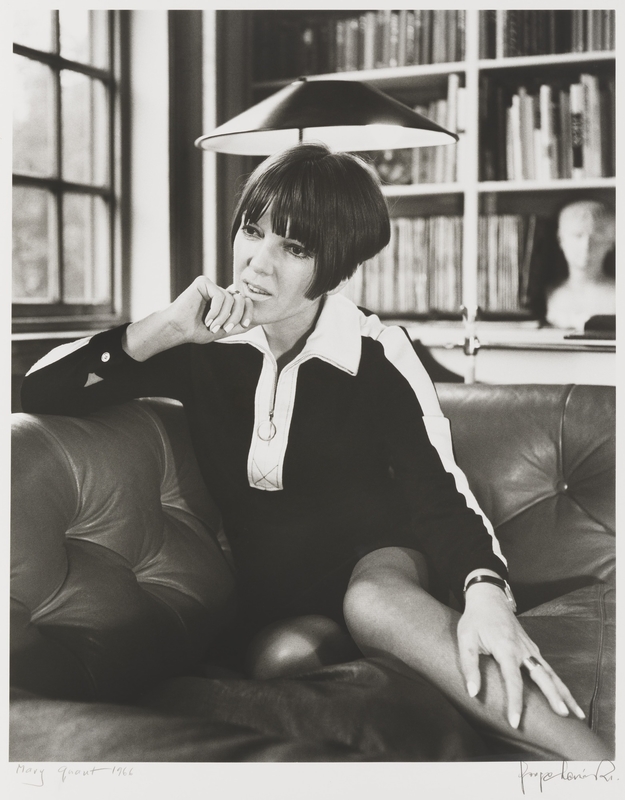

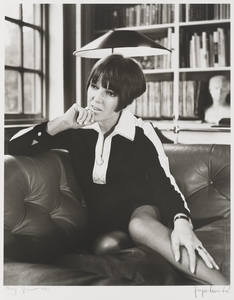

Only a few years earlier, fashion had allied itself with everything in art that was new and modern. In the wake of the trail blazed by Mary Quant in the late 1950s with her youthful miniskirts and geometric shapes, London had supplanted Paris as the leading fashion capital.

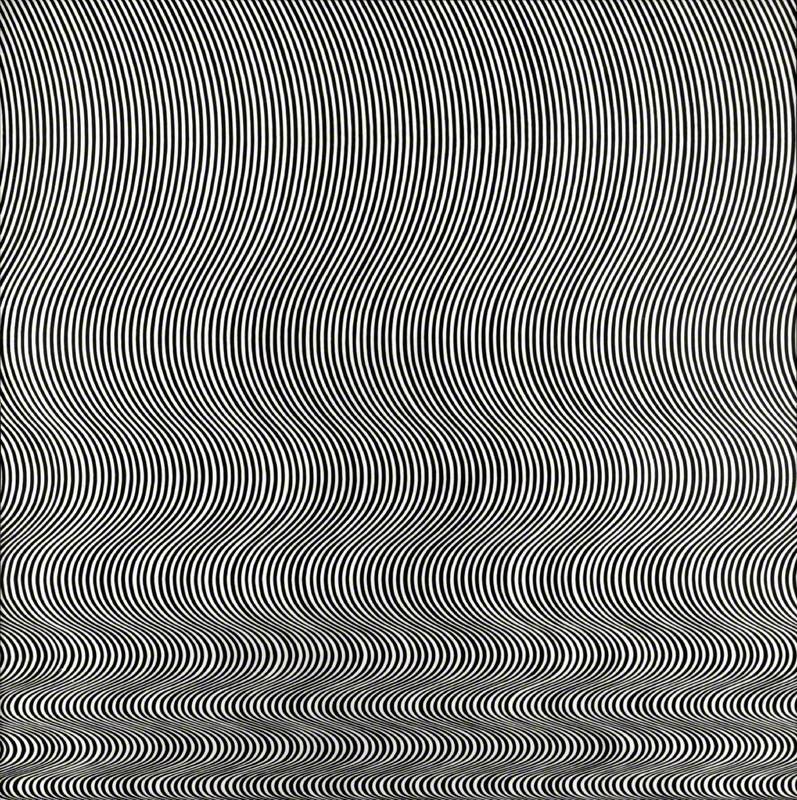

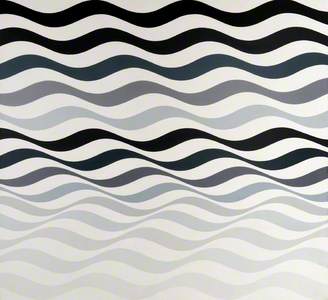

The dazzling optical patterns of the Op Art movement inspired fun skirt suits by London designers such as Foale and Tuffin, and legendary store Biba fused an Art Deco sensibility with black and white designs worthy of a Bridget Riley artwork, angering Riley herself who engaged in legal action to protect her work from commercial use.

Maxi dress with medieval-style sleeves, Biba, early 1970s

However, towards the latter half of the 1960s there was a turn towards nostalgia and the more romantic movements of aestheticism and Art Nouveau. As universities expanded in the 1960s and an art school education became available to people from all social backgrounds, a countercultural movement developed among the younger generation. They rejected the post-war austerity they had grown up with and rebelled against the values and wardrobes of their parents and the prevailing politics of conformism. Sceptical of new technology in the light of the threat of nuclear annihilation, they embraced peace and love, and turned to the past for comfort and inspiration.

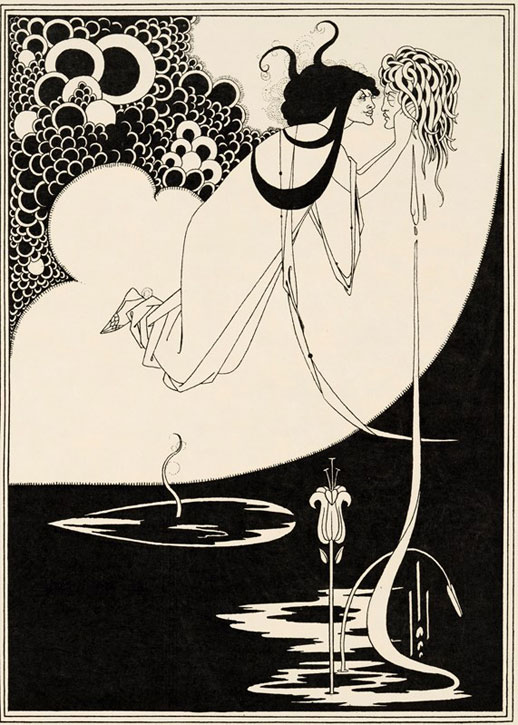

Illustration for Oscar Wilde's 'Salomé'

1893, drawing by Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898) published in 'The Climax'

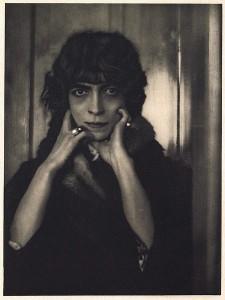

Attending the Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898) exhibition held at the V&A in 1966, jazz musician and writer George Melly was struck by the youthfulness of the crowd he saw there. Observing the art students and 'Beats' he noted: 'I believe now... that I had stumbled for the first time into the presence of the emerging Underground'. Beardsley's erotic black and white drawings for Oscar Wilde's Salomé, published in 1894, generated just the kind of outrage that the new underground press, epitomised by International Times and Oz magazine, sought to provoke.

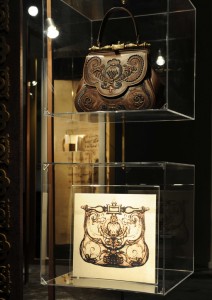

Tableau representing Hung On You boutique at the Fashion and Textile Museum

The boutiques loved Beardsley too. His sinuous lines and elaborate detail, typical of Aesthetic poster art, prompted society couple Michael Rainey and Jane Ormsby Gore to ask graphic designer Antony Little to create a Beardsley-style mural for the backdrop to their boutique Hung On You, visible in this tableau recreation on display at the Fashion and Textile Museum's current 'Beautiful People' exhibition.

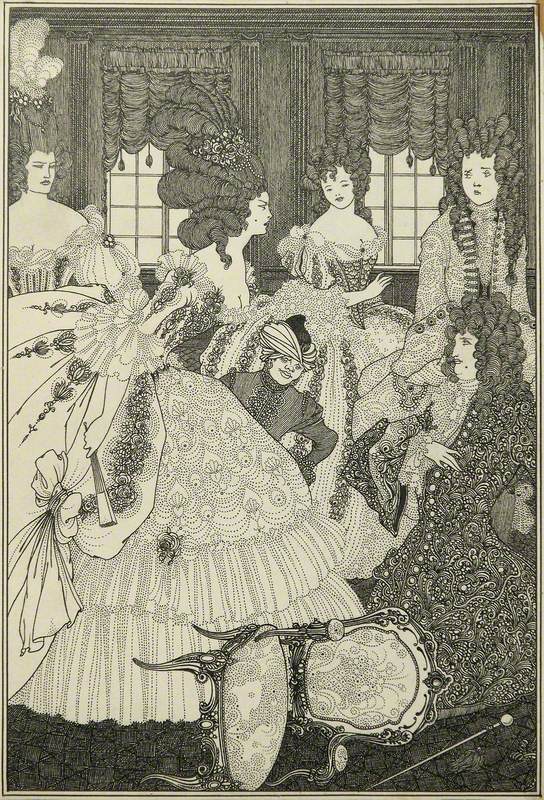

The Battle of the Beaux and the Belles

c.1896

Aubrey Beardsley (1872–1898)

The store's collection echoed the extravagantly fashionable beaux and belles depicted in Beardsley's drawings, offering richly coloured satin and velvet suits for men, some tailored from vintage fabrics. High-buttoned jackets and ruffled shirts recalled the original dandy of Regency England, parading the streets in his impeccable tailoring.

Across the music scene, brocade and tapestry jackets with a high-stand collar formed part of the rock-star wardrobe, adorning performers from The Beatles to Pink Floyd.

Gear on the Warpath: Mick Jagger in a Grenadier Guards jacket, 1967

Victorian military uniforms from boutiques like I Was Lord Kitchener's Valet were worn subversively by the likes of Mick Jagger and as part of artist Peter Blake's Victorian scrapbook-style cover design for The Beatles' Sergeant Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album, causing offence to war veterans while thrilling young fans.

Happy Birthday artist Peter Blake, responsible for co-creating the Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band album cover pic.twitter.com/ej1XorEhkv

— Saatchi Gallery (@saatchi_gallery) June 25, 2015

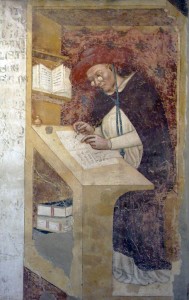

At the Royal College of Art, where Peter Blake had studied alongside David Hockney, a new generation of talented fashion designers emerged, including Ossie Clark, Zandra Rhodes and Bill Gibb. Their tutor, textile designer Bernard Nevill, taught them the history of fashion through frequent visits to the V&A, introducing them to Art Deco, Art Nouveau and the work of Russian artist Léon Bakst.

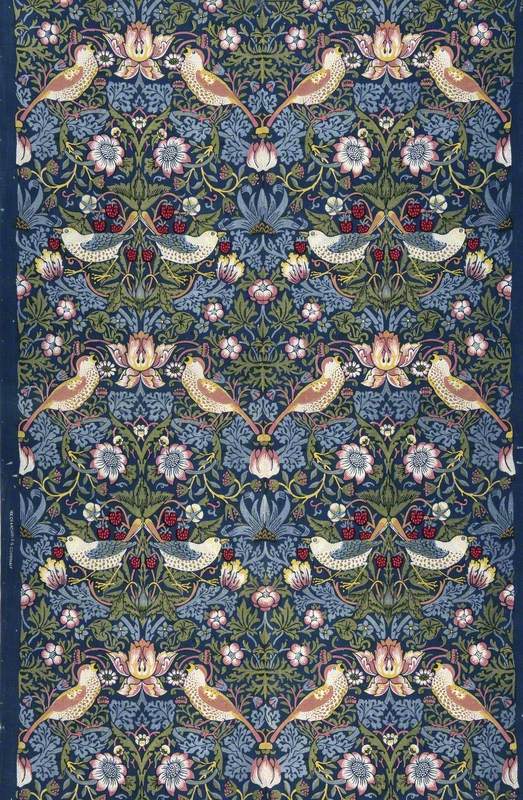

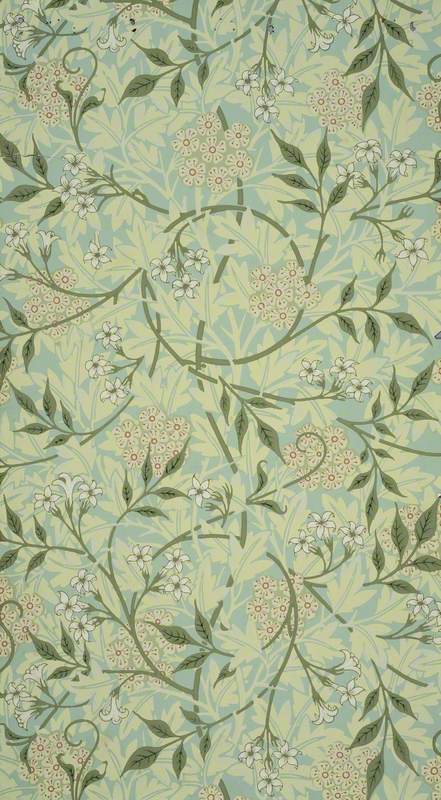

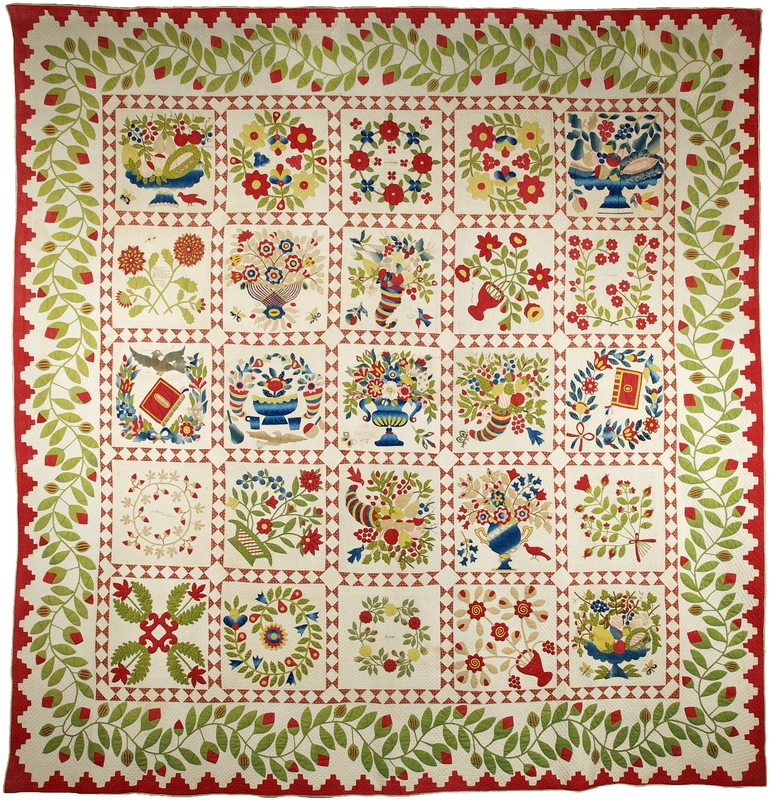

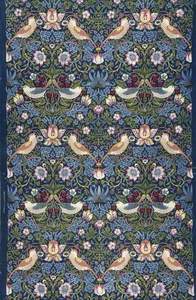

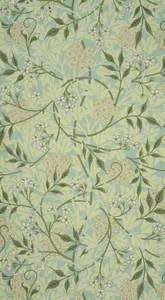

Formerly director of design at department store Liberty, which had long championed Aesthetic style, Nevill set his students a project using William Morris designs, just ahead of a relaunch of Morris' fabrics at the store. Victorian flower designs were appearing again in home furnishings, particularly targeted at affluent young people setting up their first homes.

The revival of interest in Morris and the Art Nouveau style chimed well with the utopian vision of bohemians and hippies whose interest in ecology and conservation movements looked back to a simpler time where nature was central to life. Morris believed in expressing truth in nature, designing only from British fauna and flora and rejecting the rapidly industrialising world in his quest for beauty and the revival of crafting by hand.

Morris, in harmony with the Pre-Raphaelite painters, sought to recapture the spirit of Medieval chivalry and romance, myth and legend. Graphic and textile designers alike were drawn by the whorling curves and twisting representation of plants found in Art Nouveau patterning. Poster artists developed new bulbous typefaces and incorporated sensuous female figures into their designs, inspired by the Czech artist Alphons Mucha whose work adorned the walls of so many student bedrooms.

'Reverie', poster for the publishing house Champenois

1897, poster by Alphonse Mucha (1860–1939)

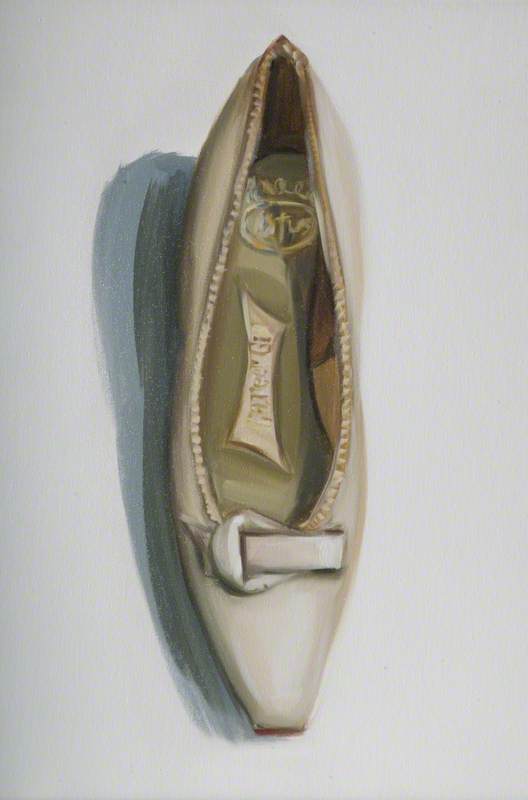

Out of the Morris revival came one of the most photographed jackets of the period. It was produced by influential boutique Granny Takes a Trip, founded in 1966 by graphic designer Nigel Waymouth and vintage dress collector Sheila Cohen.

Nigel Waymouth (right) outside Granny's in 1966

1966, photograph by unknown

Using William Morris' 'Golden Lily' furnishing fabric they created a three-buttoned jacket worn, among others, by George Harrison of The Beatles and Roy Wood of The Move. The designer Ossie Clark wore a version of it to attend an exhibition of work by his artist friend Patrick Procktor in 1968, assuring its iconic status as part of the modern dandy's wardrobe.

William Morris jacket by Anna Sui

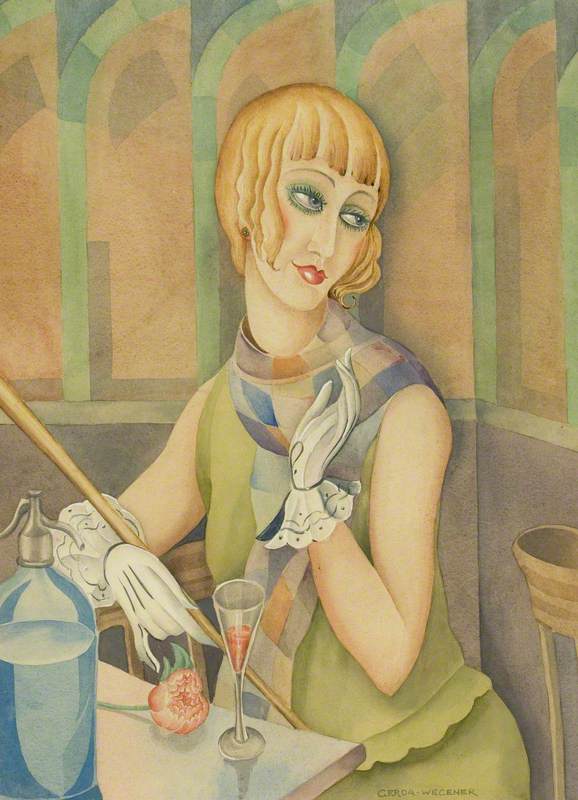

Ossie Clark took the revivalist style to another level with his beautifully proportioned, fluid silhouettes which owed much to bias-cut 1930s dresses he discovered in the Portobello Road market. Clark was part of the influx of talent from the North who studied under Bernard Nevill at the RCA and he formed close friendships with David Hockney, with whom he had a brief affair in 1964, and Celia Birtwell who had studied textile design at art college in Salford. Clark and Birtwell were later to marry. Nevill noted that Clark was 'hooked on glamour', and while he was still a student he and Birtwell were snapped up by Alice Pollock to design collaboratively for her boutique Quorum, a leading style-setter of the period.

Satin trousers and jacket, Ossie Clark for Quorum, print by Celia Birtwell, 1968

The Sleeping Beauty: The Prince Discovers the Princess and Wakes Her with a Kiss

1913–1922

Léon Bakst (1866–1924)

Celia's textile designs drew on a number of historical reference points. She was particularly influenced by the Sotheby's auction in 1967 of vintage costumes designed by Léon Bakst for the Ballets Russes and, in this loose flowing trouser ensemble by Clark for Quorum, the combined the influences of Bakst's designs with their intense colours, echoed in his paintings, can be seen alongside Art Deco graphic shapes.

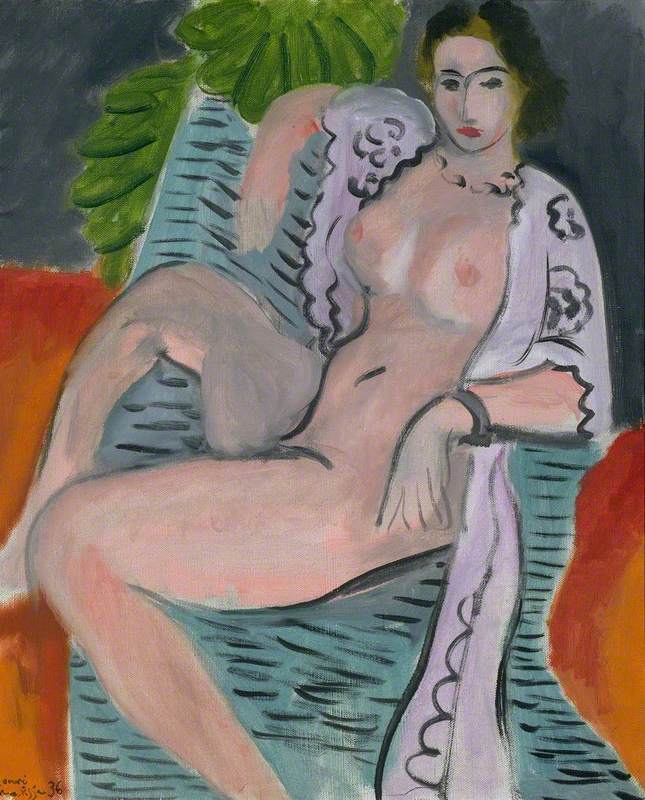

Celia also incorporated Matisse's floral motifs into her work, particularly the cut-out flowers of his later work. The light wrap draped over Matisse's nude in this painting could have come straight out of an Ossie Clark/Celia Birtwell collection. The perennial appeal of Celia's poppy print, featured in this androgynous top, means that it is still being used in high-street collections today.

Shirt in Poppy print, Ossie Clark for Quorum print by Celia Birtwell, 1968

Hockney was a staunch supporter of Clark's work, attending his runway shows and designing the programmes, but it was Celia to whom he was closest and who became his lifelong muse. She features in numerous of his works, often wearing Ossie Clark garments. In Mr and Mrs Clark and Percy, a portrait of the couple in their Notting Hill Gate flat, one of his nostalgic dresses is given prominence.

Although some critics have suggested that the pregnant Celia is portrayed standing as an indication of her elevated status in the relationship, Hockney denied this, saying: 'It's really because I thought the dress looked better that way'.

Celia wears Ossie Clark's black moss crepe wraparound dress with a flowing neck sash and black sleeves twined with red, designed in 1969. The spiral seams of the sleeves were a technique Clark had learned from studying dresses from the 1930s, but the overall effect is of a Pre-Raphaelite heroine. The fluid dress skimming her body, combined with her statuesque pose, ringleted hair and limpid eyes conjure up the figure of Jane Morris, wife of William Morris and Dante Gabriel Rossetti's muse.

The Fool inside The Beatles' Apple Boutique on the corner of Baker Street and Paddington Street

The heyday of the 'beautiful people' and their boutiques lasted only a few years. Many of the shops fell prey to widespread shoplifting and a cavalier approach to accounting. By the time the 1970s dawned, increasing levels of unemployment and hardship brought an end to the utopian dream. But while it lasted, its brilliant stars had reconnected with an artistic heritage that produced some of the most exciting fashions London had ever known.

'Beautiful People: The Boutique in 1960s Counterculture' continues at the Fashion and Textile Museum, London, until 13th March 2022

Further reading

Marnie Fogg, Boutique: A '60s Cultural Phenomenon, Mitchell Beazley, 2003

Dominic Sandbrook, White Heat: A History of Britain in the Swinging Sixties, Abacus 2006

Emma Baxter-Wright, Vintage Fashion: Collecting and Wearing Designer Classics, Carlton Books Ltd, 2006