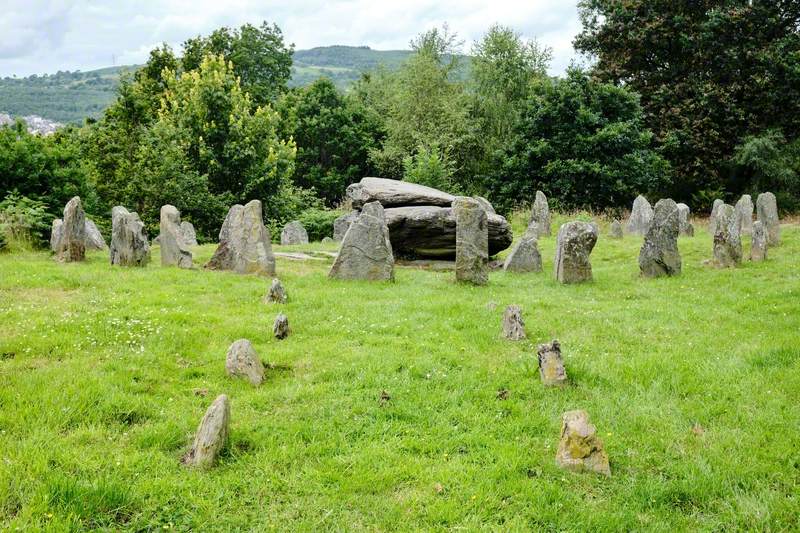

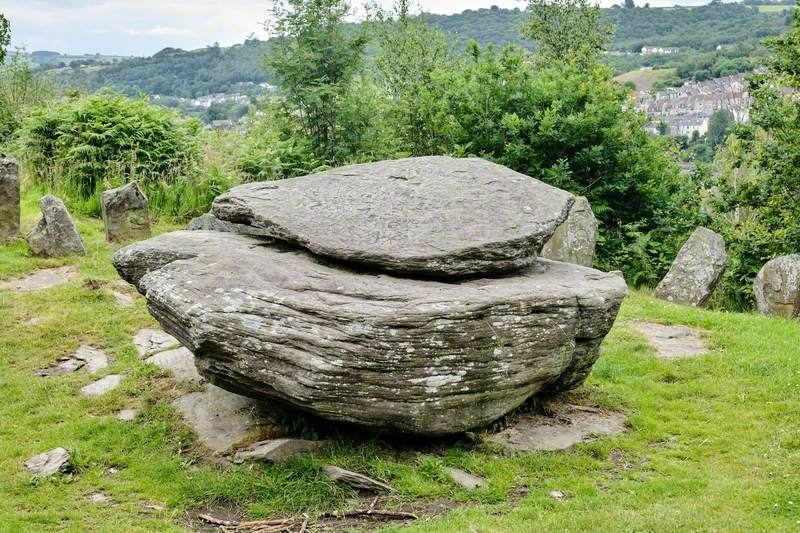

On the brow of Coedpenmaen Common in Pontypridd, serenaded by the droning hum of the A470 below, sit two imposing boulders of Pennant sandstone, one balancing atop the other. This striking glacial remnant of the valley's last Ice Age, dating from some 11,500 years ago, is known as Y Maen Chwŷf, or Rocking Stone, and has been revered as a nucleus of Welsh culture for centuries.

Known as Newbridge until 1856, following construction of William Edwards's iconic 1756 structure – the longest single-span bridge of its day in Europe – Pontypridd itself is a relatively new town, built on the back of the Industrial Revolution that swept through the south Wales valleys during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

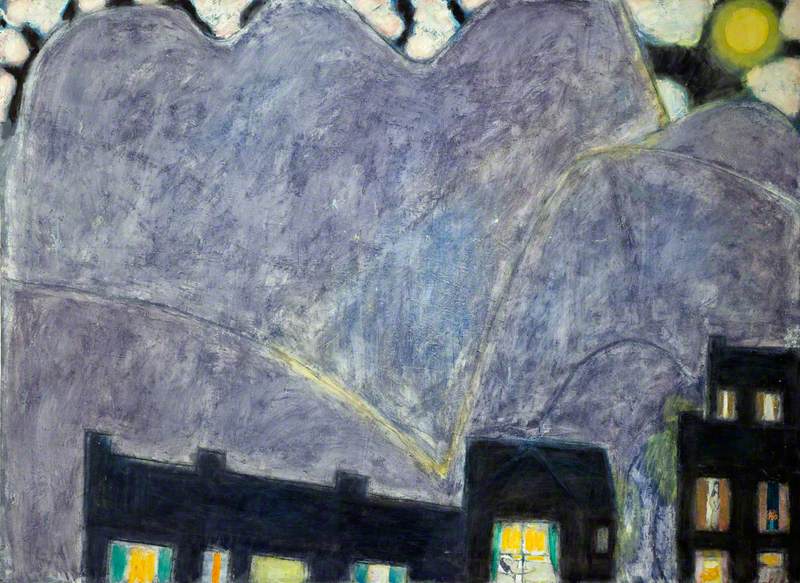

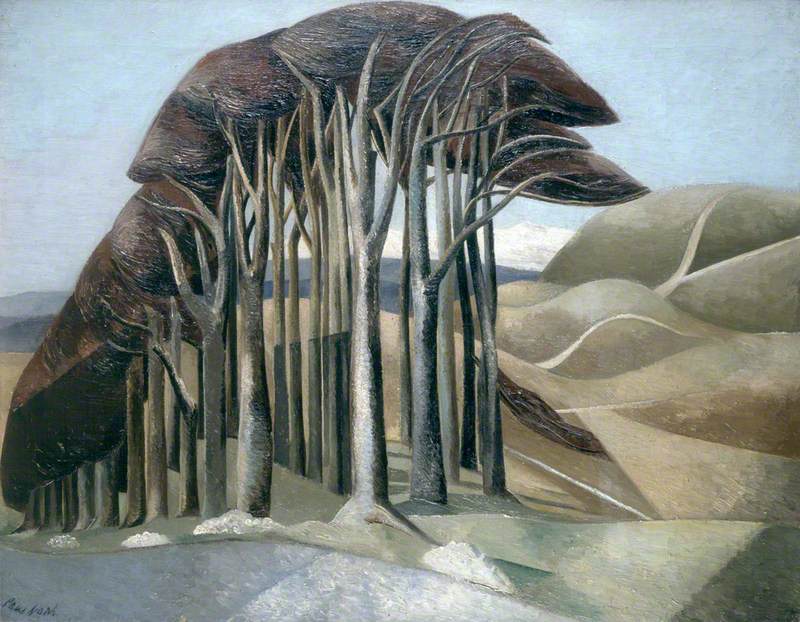

The Bridge at Pontypridd

c.1760

E. B. Edwards

As the population here flourished, to the east of the Old Bridge, the Maen Chwŷf became a convenient focal point for local Christian congregations, who gathered around it for weekly prayer meetings. Until the end of the nineteenth century, a fair was held on the common each Easter Monday, with the stone featuring at the centre of the celebrations.

However, it was with the arrival of stonemason, poet, master forger and cultural icon Edward Williams – better known by his bardic name Iolo Morganwg – that Y Maen Chwŷf developed an altogether different purpose. Fanned by the antiquarian flames of the London Welsh's Romantic ideals concerning druids and Celticity, Iolo sought to establish an invented bardic tradition by introducing the world to the Gorsedd of the Bards of the Isle of Britain – an association of notable figures recognised for their contribution to the promotion, development and enrichment of Welsh culture.

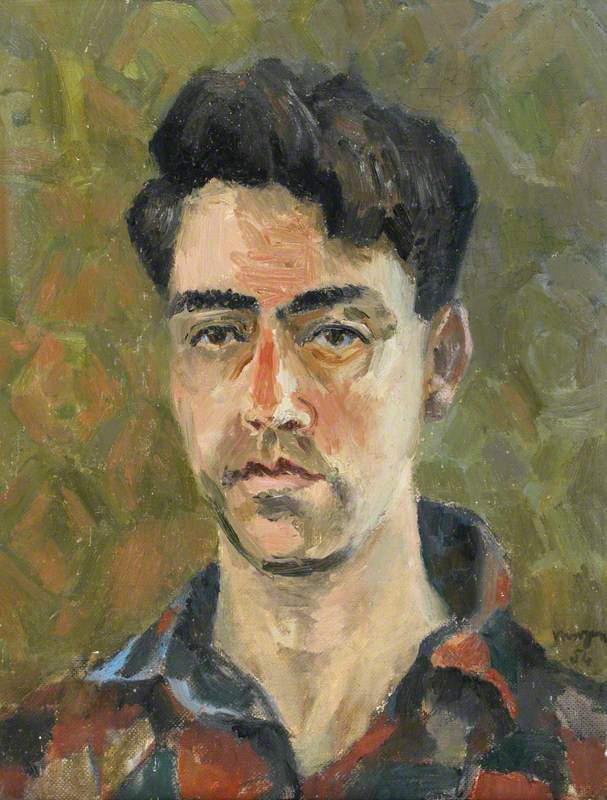

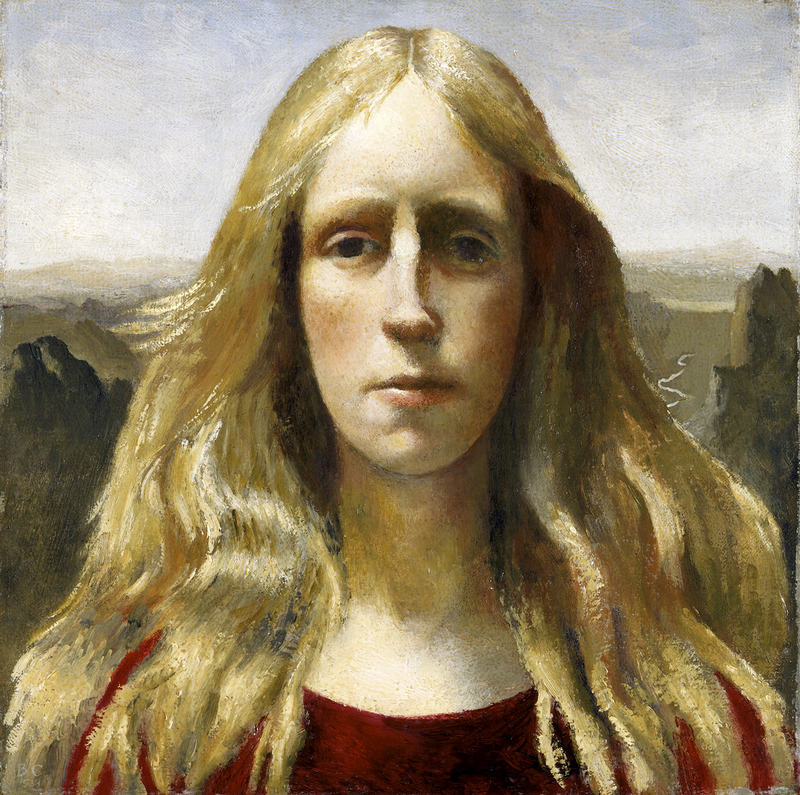

Iolo Morganwg (Edward Williams) (1747–1826)

1896

William Williams (Ap Caledfryn) (1837–1915)

While the first ceremony was held in front of a curious crowd on Primrose Hill in London in 1792, successive gatherings across Wales followed. In turn, Iolo's Glamorganshire roots brought him to the Rocking Stone, which he lauded as an irrefutable ancient druidic monument, performing the first of many Gorsedd ceremonies there on 1st August 1814.

Druid mania certainly did not die with Iolo; his many disciples continued to embroil themselves in Rocking Stone Gorsedd rituals for years to come. In the 1830s, the society known as Cymdeithas Cymreigyddion y Maen Chwŷf (The Welsh Scholarly Society of the Rocking Stone) was formed, largely spearheaded by one of Iolo's most notable followers, Thomas Williams (bardic name Gwilym Morganwg) – landlord of the nearby New Inn. Here, regular eisteddfodau were held, often in conjunction with Gorsedd gatherings, nurturing the talents of local poets, musicians and scholars. Gwilym himself had been initiated at the Rocking Stone in 1814, alongside Iolo's own son Taliesin Williams (Taliesin ab Iolo), who posthumously and uncritically published much of his father's most influential manuscripts and forgeries.

While much of the groundwork for the burgeoning neo-druidic movement in Pontypridd was now successfully laid, it was local clockmaker and preacher Evan Davies – later known as Myfyr Morganwg – who eventually succeeded in establishing Y Maen Chwŷf's place in Welsh cultural history.

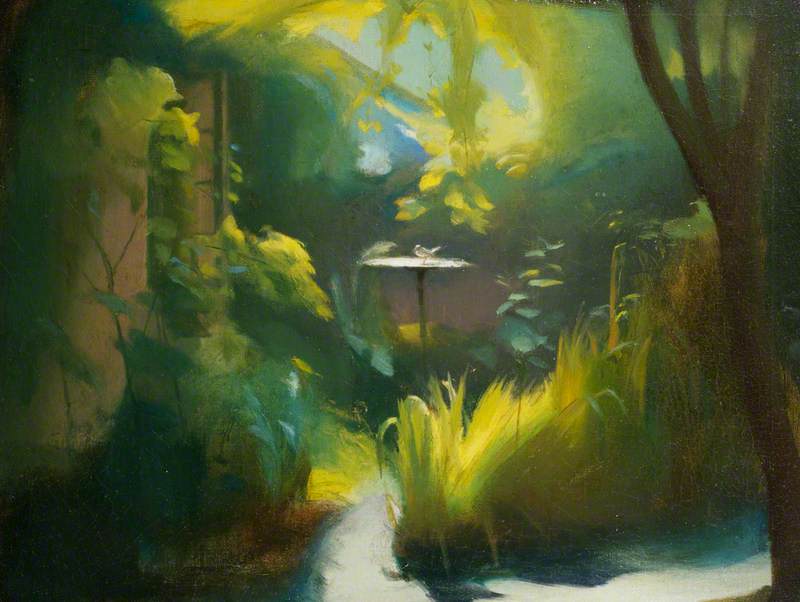

Evan Davies, Myfyr Morganwg (1801–1888)

late 19th C

William Williams (Ap Caledfryn) (1837–1915)

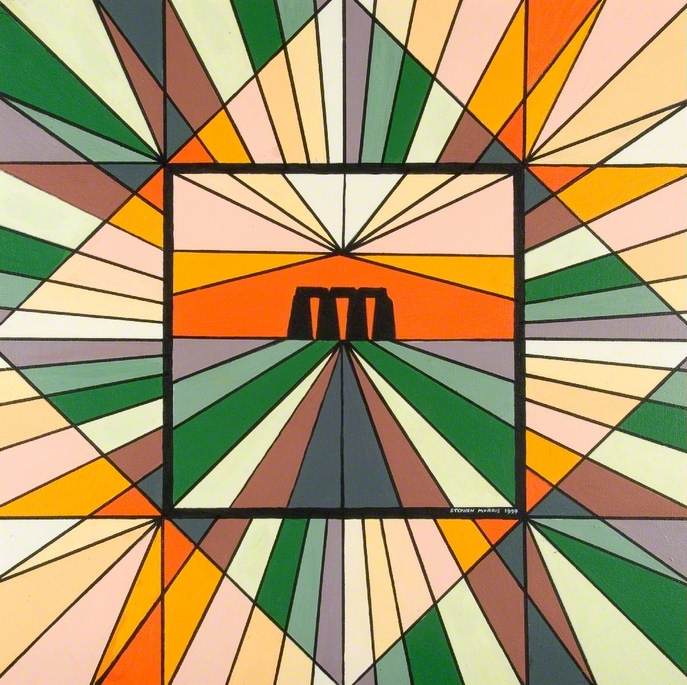

Inspired in part by the antiquarian periodical Asiatick Researches, Myfyr claimed to have unlocked the secrets of the ancient druids and set to work establishing his own doctrine in Pontypridd. While his vision was a far cry from that previously espoused by Iolo, Myfyr was similarly influenced by the works of earlier antiquarians such as William Stukeley and John Aubrey. It should therefore come as no surprise that in 1849, he commissioned a ceremonial double stone circle around the Rocking Stone in a bid to cement its status as an ancient druidic temple. His design was completed with a series of smaller stones, set out in the form of a Stukeley-esque serpent, winding its way across the hill with the Rocking Stone at its centre.

With mounting confidence, in 1852 Myfyr proclaimed himself 'Archdruid of the Isle of Britain' – a title which both Iolo and Taliesin had previously shunned. Up until his 78th year, he continued performing increasingly eccentric and flamboyant quarterly rituals to his followers while standing barefoot on the Rocking Stone, staff in hand and coat buttonholes adorned with mistletoe.

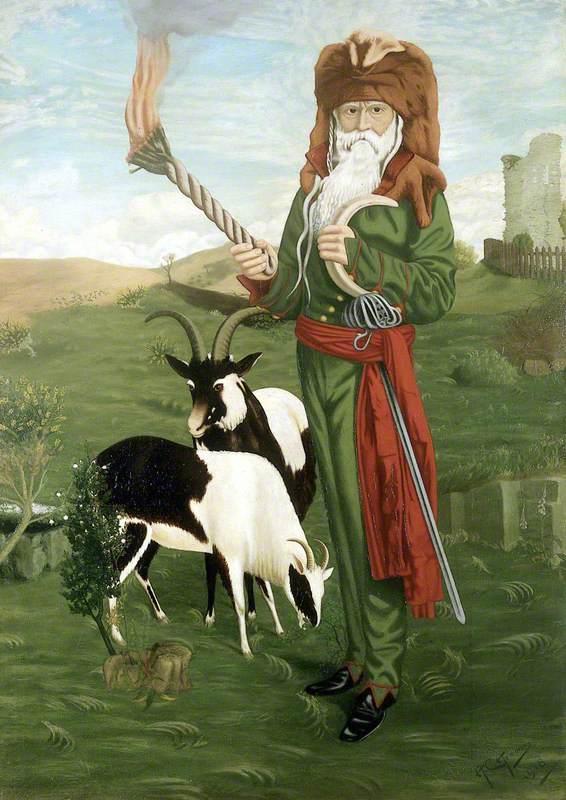

William Price of Llantrisant, in Druidic Costume, with Goats

1918

Alfred Charles Hemming (active 1904–1933)

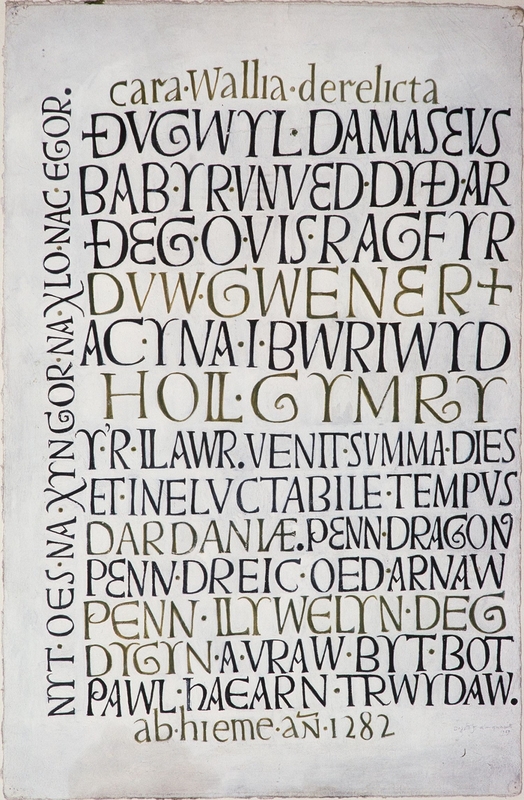

One of Myfyr's most vocal critics was none other than pioneering surgeon, nationalist and self-proclaimed rival Archdruid, Dr William Price. Furious that Myfyr's claim to the title had been largely accepted by his peers, Price developed his own druidic doctrine by which he could claim supremacy as the true Archdruid of Britain. This came in the form of a cryptic manifesto for the future of Wales, the contents of which allegedly appeared to him in a prophetic vision while in the Louvre in 1839, which he dubbed Gwyllllis yn Nayd, or 'The Will of my Father'.

View this post on Instagram

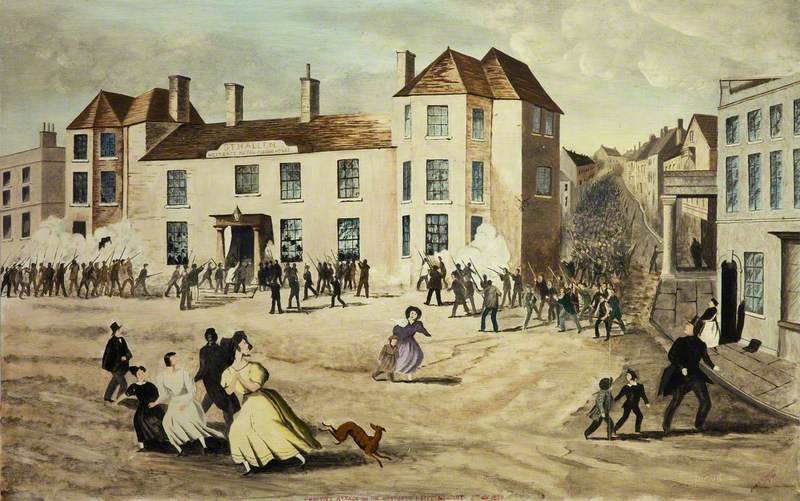

Like Myfyr, Price himself had previously attempted to safeguard the Rocking Stone's legacy following several attempts to destroy it by disgruntled locals. In 1838, he implored subscribers to contribute towards the building of a 100-foot-high tower on the common which would serve as a museum of Welsh culture, topped with a camera obscura, at an estimated cost of £1,000. As with many of Price's more ambitious and arguably ill-conceived ventures, he failed to collect sufficient funding. The project was finally doomed when the doctor was forced to flee to France to avoid prosecution following his integral role in the Chartist movement and his association with the Newport Rising of 1839, leading in turn to his prophetic Parisian epiphany.

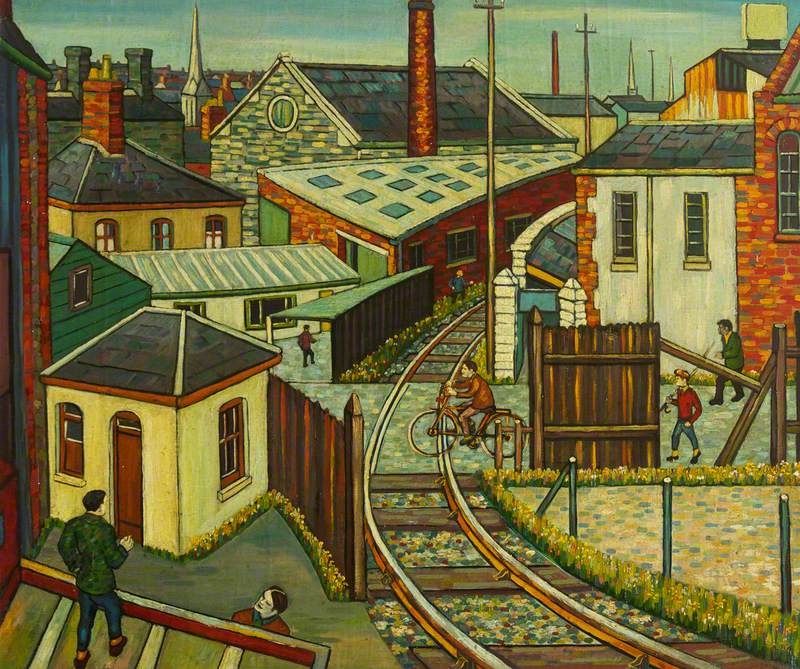

Chartist Attack on the 'Westgate Hotel', Newport, 3rd November 1839

1970

Bert Canham (active 1969–1971)

Egos aside, to many of these neo-druids, the Maen Chwŷf represented a pre-Christian communion table, a sacred temple and the ark of the goddess Ceridwen. It was believed to carry the sap of the sun's rays in the form of a sacred mundane egg, deemed responsible for creation itself, steeped in imagery derived from the mythology and theology of other world cultures – albeit repackaged with a Welsh twist and some inventive etymological interpretations.

These varying beliefs were recorded across several volumes by Western Mail journalist and final acting Archdruid, Owen 'Morien' Morgan, whose death in 1921 signalled the end of the neo-druidic movement in Pontypridd and the Rocking Stone Gorsedd.

Today, the smaller of these two boulders nestles comfortably and unmoving on the brow of the largest, its uppermost surface gouged by the carved initials of generations of well-wishers and bored teenagers. While the local community may not congregate here in their thousands to attend lectures and prayer meetings, or immerse themselves in the colourful neo-druidic rituals of their forefathers, the Maen Chwŷf remains a beacon of Pontypridd identity. It is as important in its influence within the local landscape as the Old Bridge, the anthem, the chinaworks and chainworks, the poets and musicians, and – dare I say it – even Tom Jones.

Now with the 2024 National Eisteddfod making its way to Pontypridd, its history, and that of its motley congregation, remains as relevant as ever.

Dr Delyth Badder, folklorist and author

This content was supported by Welsh Government funding

Further reading

Ronald Hutton, Blood and Mistletoe: The History of the Druids in Britain, Yale University Press, 2009

Geraint H. Jenkins (ed.), A Rattleskull Genius, University of Wales Press, 2005

Owen Morgan (Morien), History of Pontypridd and Rhondda Valleys, Glamorgan County Times, 1903

Rhys Mwyn, Cam i Forgannwg, Gwent a Brycheiniog: Safleoedd Archaeoleg yn Ne-ddwyrain Cymru, Gwasg Carreg Gwalch, 2024

Dean Powell, Dr William Price: Wales's First Radical, Amberley, 2014