Perusing the art historical literature over the last 30 years or so, there has been a lot of interest in women artists. Just one example is the brilliant Elizabeth Southerden Thompson Butler, the Victorian military painter.

When we go back to the sixteenth century we find a few women painters in the Italian States such as Lavinia Fontana and Sofonisba Anguissola. The latter was Cremonese; the town of Cremona was later famous as the home of the violinmaker Stradivarius.

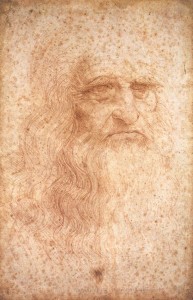

Image credit: Southampton City Art Gallery

The Artist's Sister in the Garb of a Nun 1551

Sofonisba Anguissola (c.1535–1625)

Southampton City Art GalleryFrom the artist’s early period in Cremona, we have the charmingly mysterious portrait of a nun (The Artist’s Sister in the Garb of a Nun) in the collection of Southampton City Art Gallery. Her acknowledged masterpiece is the Three Children in the private Methuen collection at Corsham Court in Wiltshire, and thus outside the remit of the Art UK project.

Image credit: Łańcut Castle, public domain (source: Wikimedia Commons)

Self Portrait at the Easel

1556, oil on canvas by Sofonisba Anguissola (c.1532–1625)

At a young age, Anguissola left Cremona and went to work in Spain where she was successful as a court artist. Unfortunately, she hardly ever signed her pictures and her work in Spain has been confused with Spanish portraitists such as Alonso Sánchez Coello and possibly even El Greco. The artist then left Spain, married a Genoese merchant, was widowed, and retired to Sicily. It is there that our story ends. At a very great age, she was painted by the young Anthony van Dyck, and this picture survives at Knole in Kent.

Knole is a rambling house and does not lend itself to circulation as there are dead ends after suites of rooms which run into one another. To keep the whole house open requires a full complement of room guardians and if there is the odd staff shortage the National Trust uses its only weapon, the protective rope. The Van Dyck hangs above a door just inside one of these sets of rooms.

On a visit not so long ago I tried to see the picture but no amount of neck-craning could do it. However, I was with a more intrepid colleague and he, like the ‘man who asked for a glass of whisky in the Pump Room at Bath’, asked for the rope to be moved. They were very nice and they obliged. But I could not help thinking of my colleague, Benedict Nicolson, whose mother Vita Sackville West had been born at Knole. He had been annoyed by the difficulties of getting photographs from French museums, and in despair he remarked ‘It would provide material for a Kafka novel’.

Christopher Wright, Art UK advisor, art historian, artist and author of numerous catalogues of Old Master paintings in Britain