In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

Laura Ford (b.1961) is a Welsh artist who having grown up around a theatrical fairground family has developed playful, humorous and often disquieting emotional narratives around her sculptures. She explores hybrid characters, neither wholly child nor animal, but which unlock our inner vulnerabilities and engage our child self. I caught up with Laura during the opening week of her new solo exhibition, 'Laura Ford: Under this Roof'.

Image credit: Bo Lee and Workman

Laura Ford in the studio

Melissa Munro: You grew up in Porthcawl, a seaside resort in south Wales. I've heard you talk about gaining interest in art as a teenager when you began visiting galleries in Wales. Can you remember what inspired you to go to art school?

Laura Ford: I used to be taken to the Glynn Vivian Art Gallery quite a lot with my Auntie Margaret who had been to art school. My other aunt would take me to the National Museum of Wales because she would take us as chaperones when she would go on dates. It did mean I got to see a lot of art that I wouldn't have seen otherwise, like Ceri Richards' The Lion Hunt at the Glynn Vivian.

When I was 15 a friend introduced me to David Hockney. I was really inspired by his way of drawing and knowing there was the possibility that you could be an artist. Chapter Arts Centre came much later when I started getting interested in fashion. Punk was amazing in Wales. A lot of punk followers congregated at Chapter.

Melissa: Has that played into the costume, dressing up and humour of your work?

Laura: Definitely. I think the play aspect comes from very early on. My mother gave us a playroom and we could do anything we wanted in there like paint the walls absolutely anything and it could be kept constantly messy. We had incredible games in there. Sofas became cliffs; the carpet became a sea. It allowed us as kids to be very imaginative. The dressing-up box was a massive thing. As a young kid, I would go out and sit on the sewage pipe in Porthcawl and imagine I was on a submarine going out to sea and that the rocks were castles. My approach to making sculpture is still based in that way of playing.

© the artist. Image credit: Bo Lee and Workman

Epstein's Magic

2024, painted fibreglass, fabric, steel & wood by Laura Ford (b.1961)

Melissa: In the Government Art Collection there is a work called Home (1983). You were still a student at Chelsea at the time. Can you tell me more about the context of this piece and what you were making then?

Laura: At the time there was this famous sculptor teaching me. I'm not giving any names [Laura laughs] but he said, 'I think you're a fantastic artist, but the trouble is your work is figurative and that's always going to be a problem.' So I experimented for a while in trying to make more abstracted work. For most of my time at Bath Academy, I was threatened with being thrown out because I was making the 'wrong' kind of sculpture. Later on, I went to Chelsea, and I'd got a first from Corsham – a kind of approval – and so I was getting these mixed messages of, yes, your work is really good but it's still embarrassing. It's still figurative. It's still all these things that you shouldn't really be doing. I still feel it with my work. I can look at it and think that's on the cusp of being a bit silly. I like it being on that edge, but it doesn't feel like a safe place to be.

Melissa: In 2005, you represented Wales at the Venice Biennale showing a group of works called Glory Glory which includes Hat and Horns and Beast. How did you come to form the idea for this group of work?

Laura: It came out of a series of interviews and being asked what it was to be Welsh. I found myself giving these glib answers that fed into that idea of nationalism. When I was a child, I loved dolls in national costume and I had this massive collection. I started thinking about those and how national identity can give you strength, but it can also be used to create wars and conflict. These sculptures are dressed up in national costume, but it's all mashed up, it's all wrong because all the things people think of as nationality are all misconceived anyway.

Melissa: Weeping Girls is an emotionally disturbing work of little girls who appear to be lost in the woods. There is a prevalence of children in your work, including Stilt Boy I (2001) and new pieces called Under My Roof and The Sad One (with Dogs). Has being a mother and the worries that come with that influenced your work?

Laura: I think it has because it takes you back to experiences of your own childhood but it also untaps the child self. I want the viewer to be slightly protective of them as well. The child within us is very important and we never lose those feelings. The Weeping Girls are very performative. On the one hand, they do look quite distraught, but they also look melodramatic. Are they just performing for us?

Melissa: Describe a typical day in the studio.

Laura: I don't know if there is a typical day, but it will start at 8.30ish and depends on if I have an assistant coming in, so I might be setting them up with their tasks to do. Then I will be going from one sculpture to another because I never work on one sculpture at a time. I'll stop for lunch with my husband Andrew. His studio is next to mine so we'll pop in and out and see what each other is doing. Sometimes we'll have longer chats about things, if there's a problem with the work or a solution that you can't work out. He's very good with finding technical solutions and I encourage him to bring more playfulness into his work and he encourages that in me. Then I'll finish working around 6pm.

We've been at Matt Black Barn for three and a half years. The amount of space we've got and the potential there is great. We've got a ceramics space, a working studio and a quiet studio and our home just attached to it. Having a landscape to work with as well offers so much potential for the growth of our practice.

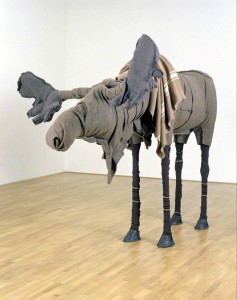

© the artist. Image credit: Bo Lee and Workman

Under My Roof

2024, steel, Jesmonite & fabric by Laura Ford (b.1961)

Melissa: Let's end with your new exhibition at Bo Lee and Workman Gallery. Could you tell us about your new work in particular the context of the title 'Under This Roof'?

Laura: The title came much later, but what I realised was that there were all these connections to the fairground, the Catholic Church and a film by Jean Cocteau called Blood of a Poet that I wrote my thesis on. There are lots of threads that join them together. In a way it's being under a roof, under God's roof, a domestic roof or a roof of a tent that you might create a show in, but also the psychological roof thinking of the mind as a roof. All of those things connecting up, that's where it came from.

View this post on Instagram

Melissa Munro, freelance writer and curator

This content was supported by Welsh Government funding

Related learning resources on Art UK