Born in Birmingham to Jamaican parents, Hurvin Anderson grew up hearing stories about Jamaica that mythologised his ancestral home. Animated by memory, imagination and personal heritage, his paintings explore his relationship to the Caribbean, a contradictory place filled with charm and beauty yet also tainted by its colonial history and present-day economic hardships.

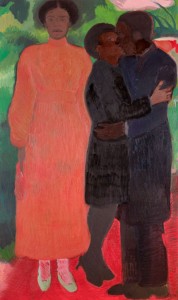

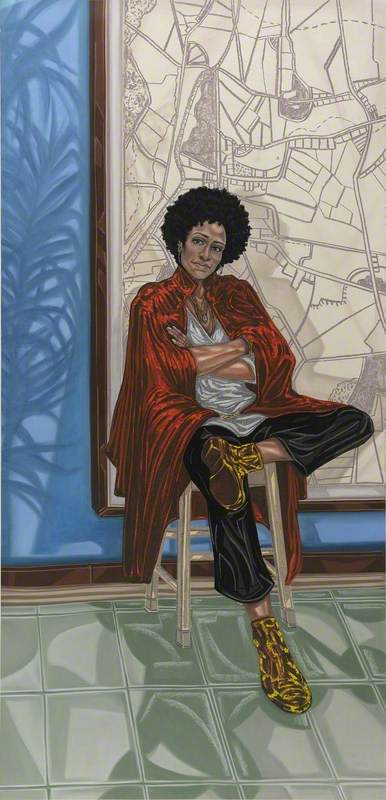

Grace Jones

2020, acrylic on canvas by Hurvin Anderson (b.1965)

Drawing from the genres of landscape, still life and portraiture, Hurvin creates open-ended images in which themes of emigration, citizenship, society and identity slip in and out of focus. From the nostalgic interiors of Birmingham's Black barbershops to the verdant landscapes of the Jamaican coast, his colour-saturated canvases hover between clarity and ambiguity. They are, he says, about being in one place but thinking of another.

His visual language blends abstraction and figuration, moving between loose, fluid brushwork and tighter, structured passages. Photographs and drawings provide a starting point, but he lets his paintings evolve intuitively, often returning to the same image and making several versions in order to better understand it.

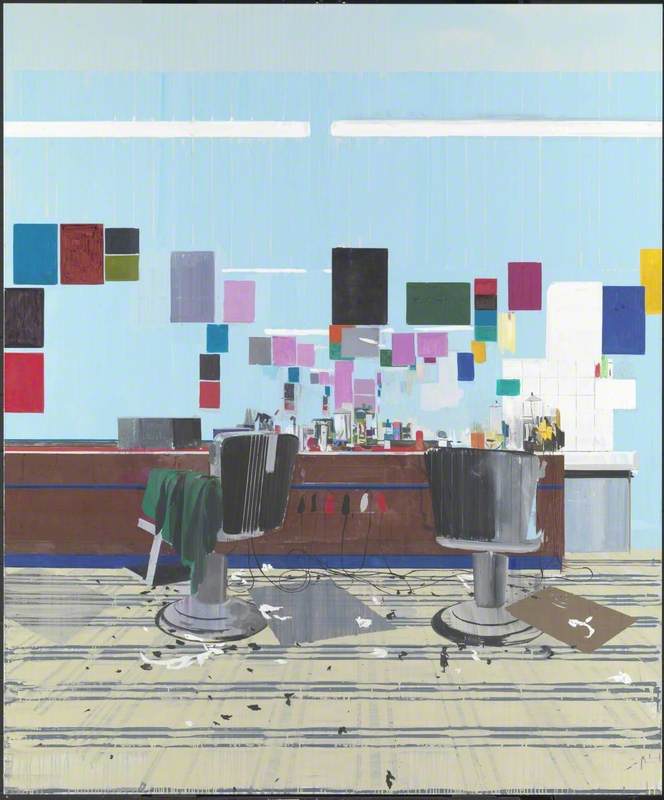

Installation view of 'Hurvin Anderson: Reverb' at Thomas Dane Gallery, London

Hurvin's solo exhibition at Thomas Dane, 'Reverb', presents a selection of paintings from his 'Jamaican Hotel Series', which focus on an abandoned hotel complex that he stumbled across while visiting the island in 2017. I spoke to the artist about the themes and ideas in these and earlier works.

David Trigg: Your recent paintings are inspired by old hotel buildings on the north coast of Jamaica, near Oracabessa. What attracted you to this subject?

Hurvin Anderson: When I saw these run-down buildings on the hillside, they intrigued me. The environment there felt inhospitable and it was as if the abandoned hotels had become like monuments. There's this idea of the Caribbean as a place where you disappear off to and enjoy, and it felt like this hotel complex was questioning that – if you can no longer enjoy going to these places, then what are they? So, there's a perception of the Caribbean and then there's the reality, and I wanted to dig into the reality in some way. I've always been intrigued by the idea of a no man's land, a kind of in-between space and what that might look like, what it might mean. These paintings are all a part of that.

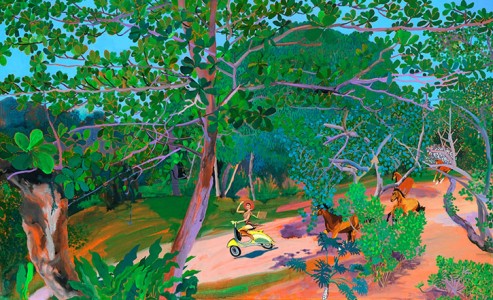

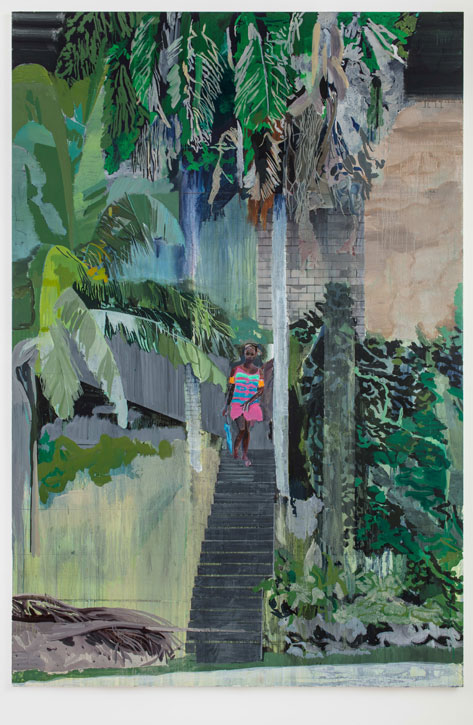

Skylarking

2021, acrylic on canvas by Hurvin Anderson (b.1965)

David: In many of the images nature seems to be taking over, almost consuming the buildings. What is the role of the natural world in your work?

Hurvin: My family talked about the country a lot when I was growing up – the country being nature – and the idea that you could live freely off the land. That's quite a strong idea in the Caribbean. So, in an odd way, nature in my work is about understanding where I came from. It's also about playing with this perception of the Caribbean being a place of lush greenery and challenging the idea that nature is always beautiful; we want to be in it, yes we do, but it is also something that can be aggressive and ominous.

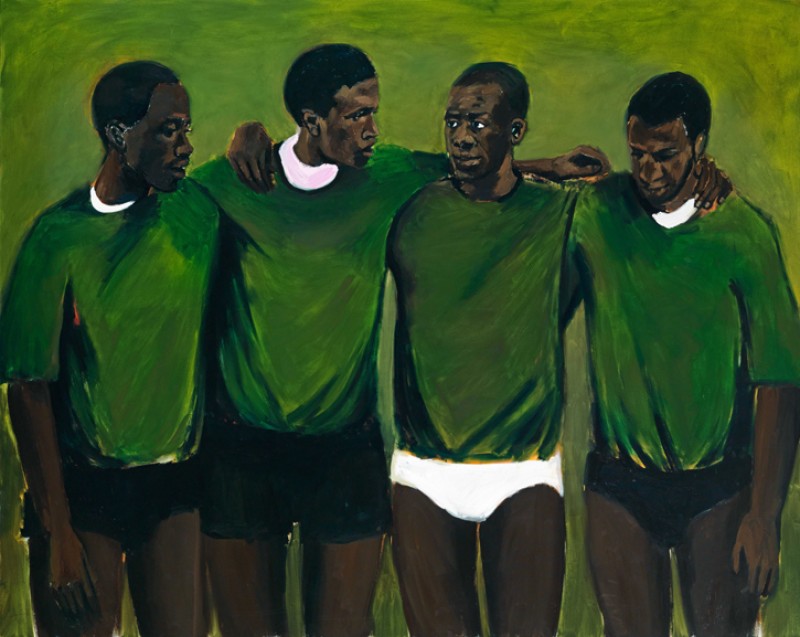

Greensleeves

2017, acrylic on canvas by Hurvin Anderson (b.1965)

David: Nature is a central element of paintings such as Greensleeves (2017) from your 'Grafting Series' (included in 'Mixing It Up: Painting Today' at the Hayward Gallery). What led you to meld together trees from different locations in these works?

Hurvin: These paintings are about my family's migration story, about overlapping worlds and the meeting of two ideas. I am the youngest of eight siblings. All my elder siblings were born in Jamaica, while I was born in the UK. For me, this has always created a tension and raised lots of questions. My brothers came here when they were 13 and they would go scrumping for fruit. I imagined that this was something they also did in Jamaica, so I decided to pull together these different times and spaces.

When I was young I heard my brothers discussing eating mangoes, and so the mango tree is symbolic of Jamaica and of the loss they experienced in leaving. The apple and pear trees are symbolic of Britain. It seemed quite apt to marry the pear and apple trees with the mango tree. The paintings are like collages in a way.

I went to Brogdale in Kent, to the National Fruit Collection, where they have all of the ancient varieties of fruit tree and that's where I learned about grafting, where young trees are grafted onto rootstock, hence the title of the series.

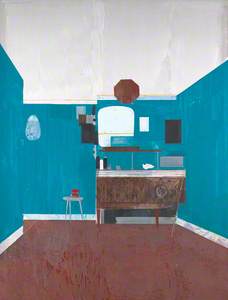

Installation view of 'Hurvin Anderson: Reverb' at Thomas Dane Gallery, London

David: Your 'Barbershop Series' paintings are among your best-known works (included in 'British Art Show 9' at Wolverhampton Art Gallery). What led you to explore this aspect of Afro-Caribbean culture?

Hurvin: I was living in London and had gone back to Birmingham to visit my Dad. I went to collect him from this local barbershop, which was in the attic room of the barber's home. I'd had my hair cut there when I was young and the barber, Peter Brown, had kept the place going. My dad was there with a few other older guys and it felt like I was going back in time. There was something about being in that place that felt like these men were keeping alive the spirit of a former age, of when they first came to this country from the Caribbean. The colour of the walls made it feel like a little bit of the Caribbean had been transported into that room. That strong blue colour felt like places I'd seen in the Caribbean where people weren't afraid to use colour. I had my camera with me and so I asked to take some photographs and things went from there.

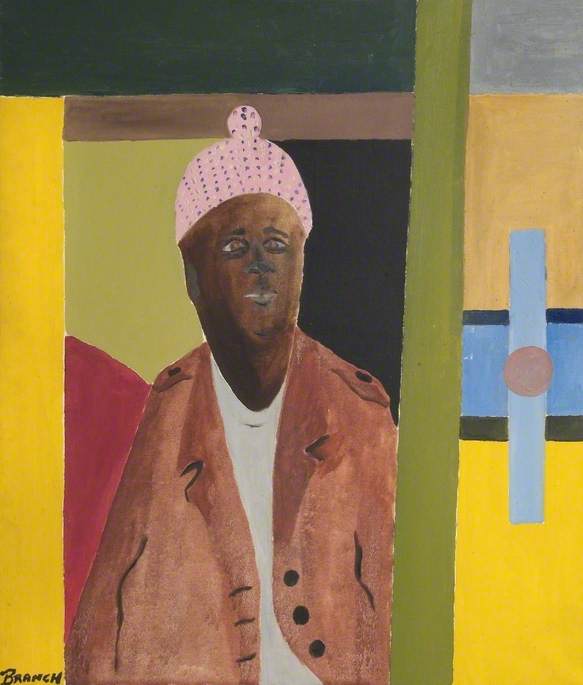

Genera Palmurum

2021, acrylic on canvas by Hurvin Anderson (b.1965)

David: Some have seen the blue, white and red colour scheme in those paintings as a tacit reference to the Union Jack, a way of nodding to questions of identity and belonging. Was that intentional?

Hurvin: No. I can't control what people see in the work. It's like when you're looking at an abstract painting and someone says they can see a face; you might get annoyed by that, but you can't stop them from seeing it. The barbershop paintings are quite open and there is space for ambiguity. Maybe through that ambiguity you can start to bring some of those questions in, but I don't want to force an opinion in my paintings.

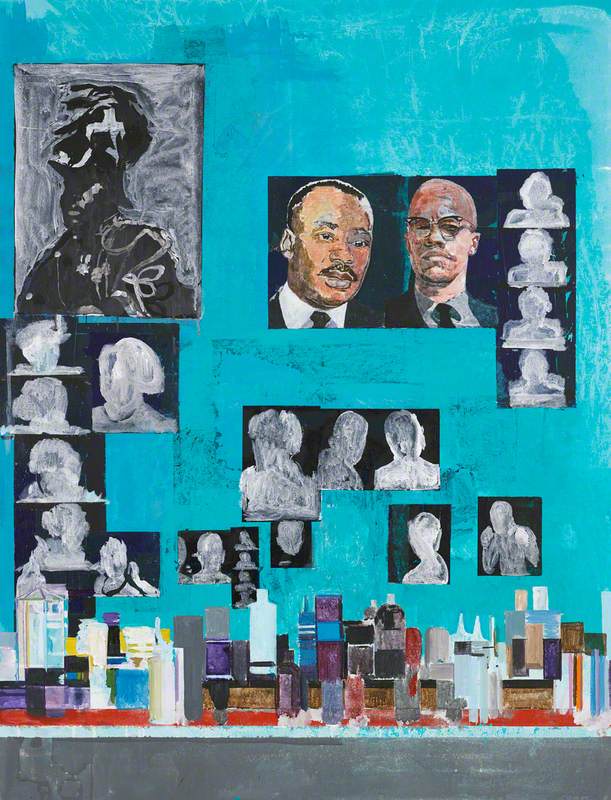

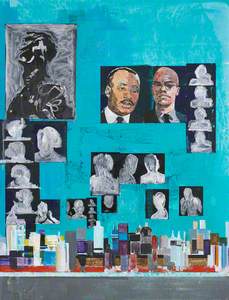

David: While politics remains a fairly subdued element of your work, your painting Is it OK to be Black? (2015–2016), in the Arts Council Collection, speaks more overtly to questions of Black identity. What prompted this work?

Hurvin: I was trying to make a painting about figures that were seen as influential to the Caribbean community. When you go to these barbershops, there's lots of photographs on the walls; you've got pictures with the different hairstyles on offer, and then there's often other people: sportsmen, political figures, actors. And this made me wonder, what are they really asking me here?

For the painting I chose Marcus Garvey, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King because these were key figures that people in the Black community were looking to. There are more ambiguous figures in there, but those are the ones that everyone knows. It's tied up with questions that were being asked about how Black people can become properly seen as part of society, how do we stop this feeling that we're being suppressed. Today we're living in an unusual moment where we are maybe finding our voice, or society is now embracing and understanding some of the questions we've been raising, but those historical figures and their ideas are still present.

The title came from a Tam Joseph painting of a barbershop, Is it OK at the Back? (1983), which is what is often said to people as they're leaving the barbershop; they have two mirrors and they check the back of your hair, and they say: 'is it OK at the back?'. But I kind of misheard it as 'Is it OK to be Black?'. So I kept the title.

Hurvin Anderson

David: What is it about painting that you continue to find so appealing?

Hurvin: I enjoy the fact that it's kind of archaic. There is a constant discussion about whether painting is dead or not, that it's an outdated medium. And, yes, maybe it is. But it's still here. There's something fundamental about it. It's like a fundamental act to want to paint, to want to represent your environment in some way. I still find it a fascinating medium and there are things I still want to do, things I want to make.

David Trigg, writer, critic and art historian

'Reverb' at Thomas Dane runs until 4th December 2021, 'Mixing It Up: Painting Today' at the Hayward Gallery runs until 12th December 2021.

A selection of Hurvin's works from the last two decades is included in 'Life Between Islands: Caribbean-British Art 1950s – Now' at Tate Britain, which runs from 1st December 2021 to 3rd April 2022.

Hurvin's 'Barbershop' paintings will be included in 'British Art Show 9' at Wolverhampton Art Gallery from 22nd January to 10th April 2022.