In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

For an artist that identifies as a sculptor, Bruce McLean's career has proved remarkably diverse over the past six decades.

During the 1960s, his time at St Martin's College of Art saw the Glasgow-born artist rebel against established ideas alongside renowned figures such as the collaborative duo Gilbert and George. By doing so he shocked the institution with his 'living sculpture' performances.

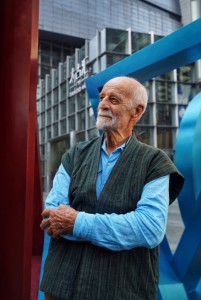

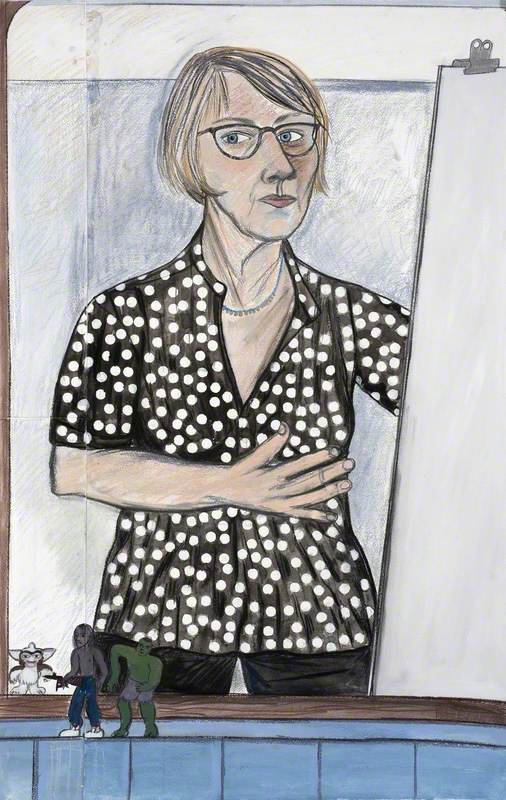

© the artist. Image credit: Reece Straw

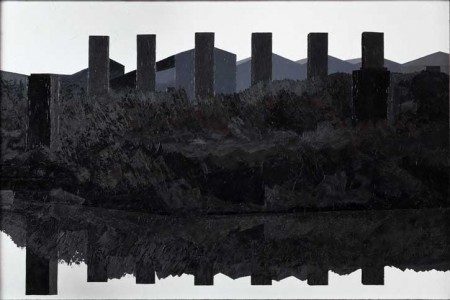

Installation view of 'Bruce McLean: Black Garden Paintings'

McLean would go on to incorporate ceramics (including a series of impractical jugs), dance, music, film and photography in his work. By the early 1980s, he turned towards a more traditional genre – painting. But he always maintained that he was a sculptor. Recent years have seen the artist focus on the theme of gardens, albeit in his familiar semi-abstract style.

Much of McLean's inspiration has come from his Spanish home in the Balearic sea, especially the patch of land developed by his wife Rosy. Now paintings of this space and other verdant plots have been brought together for a show, 'Black Garden Paintings', devised by the University of Leicester's Attenborough Arts Centre.

When in the UK, McLean works on many of his large-scale canvases at the couple's southwest London home, from where he speaks to Art UK about his current preoccupations and reflects on his long and varied career.

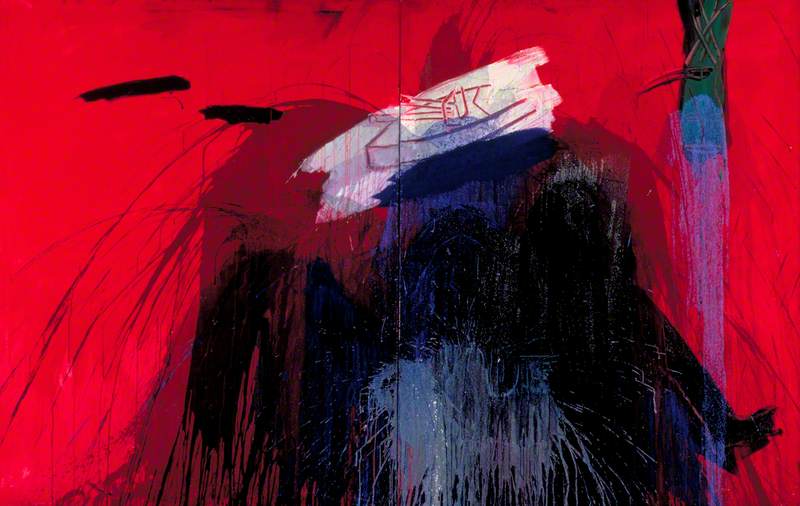

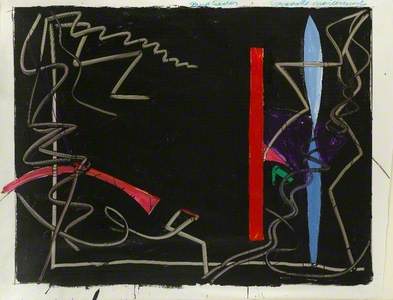

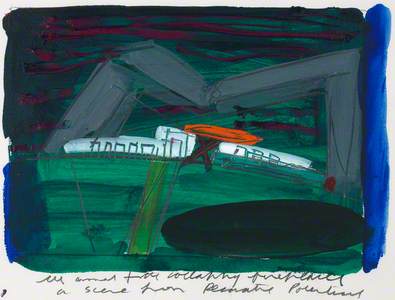

© Bruce McLean. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025. Image credit: Dundee Art Galleries and Museums Collection (Dundee City Council)

Bruce McLean (b.1944)

Dundee Art Galleries and Museums Collection (Dundee City Council)Chris Mugan: This exhibition 'Black Garden Paintings' covers work from the past 15 years. Why do you find these natural spaces so inspiring?

Bruce McLean: It's about light and colour. The first garden painting I did was in 1965 when I was still a student at St Martin's, a six-foot-by-six-foot stained canvas of some geraniums and a tree. It's quite a good painting, actually.

Then in 1981 I went to Japan to do a show and I was absolutely knocked out by the ornamental gardens, which were actually only about the size of a painting. So that's when I did Oriental Garden, Kyoto, which is about four metres by three metres, about the size of one of those gardens. I did a series of them and one won the John Moores Painting Prize in 1985, but I didn't do any more until 2006.

Since we bought the house in Menorca in 1988, my wife has been growing plants, usually ones that would thrive without water. One day I was sat looking at her working and it just came into my subconscious – not to make paintings of the garden, but inspired by it. As I get older, I just find myself sitting there more and more. Until recently, I've worked in a studio up the road where I look over the valley into the sea, so I get the colours of the water, sky and land, with the garden part of that.

© the artist. Image credit: Reece Straw

Installation view of 'Bruce McLean: Black Garden Paintings'

Chris: Your current exhibition refers to the colour black, a pigment you use a lot, especially as a background. Where does that come from?

Bruce: When you work outside in summer in Menorca you can't work on a white canvas. The light is too bright and it reflects off a canvas when it's primed with white paint. So I painted them black and found that quite interesting, because you get a better sense of colour. The colours become more intense. Black Gardens sounds a bit ominous, but it's not really. I think they're quite beautiful paintings.

© the artist. Image credit: Reece Straw

Red path, son caragol

acrylic on canvas by Bruce McLean (b.1944)

Chris: You describe your practice as 'painting as sculpture'. In fact, you have always described yourself as a sculptor. Given the wide variety of media you use, what do you mean by that?

Bruce: I am a sculptor who happens to paint. These garden paintings are two metres by two metres, they're all the same size and if you stand near them, you are in the painting, you are in the garden. In Leicester, they're all in one space so you have to look at all of them and you are drawn into the whole series.

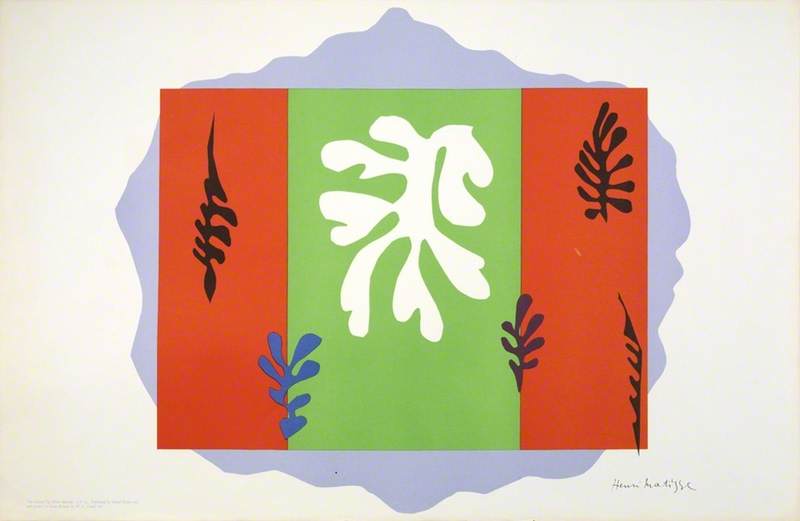

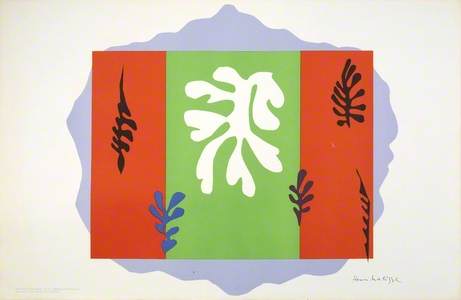

I'm thinking about sculpture all the time, but I never understood why you just had to do one thing. When I was very young I went to Saturday classes at Glasgow School of Art where I was introduced to all these great artists like Constantin Brâncuși by a man called Paul Zunterstein. I realised that Henri Matisse was a better sculptor than a painter. In fact, at the end of his life, when he was making his cut-outs, he said he was sculpting with scissors.

Chris: You studied sculpture at St Martin's under tutors such as Anthony Caro and Phillip King, where you reacted against the orthodoxy of the teaching. How did that time shape your understanding of the art form?

Bruce: It changed my life completely. It was really rigorous training, looking at what modern sculpture might be. They were very keen that we made sculpture, but also that we didn't do anything else other than sculpture, which I found very odd. I think you just do what you have to do when you have to do it. If somebody lays down rules or regulations about what it is sculpture's got to be, you immediately think, why can't it be something else?

Richard Long, Barry Flanagan, John Hilliard and me were all there at the same time. We all questioned everything they said, but that was from the training at St Martin's. I used to do impersonations of sculptures in the canteen, a quick Caro or something. George from Gilbert and George liked this idea, so we made some sculptures together.

Chris: One of your most high-profile projects to come out of that period was Nice Style, your 'pose band', where a group of you would be on stage together. That has proved influential and also inspired talks and workshops around Black Garden. What was behind that?

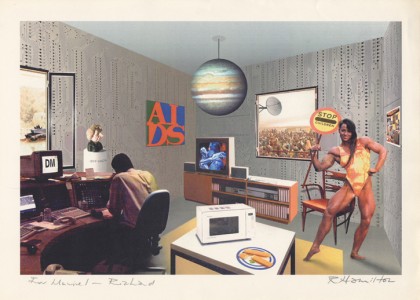

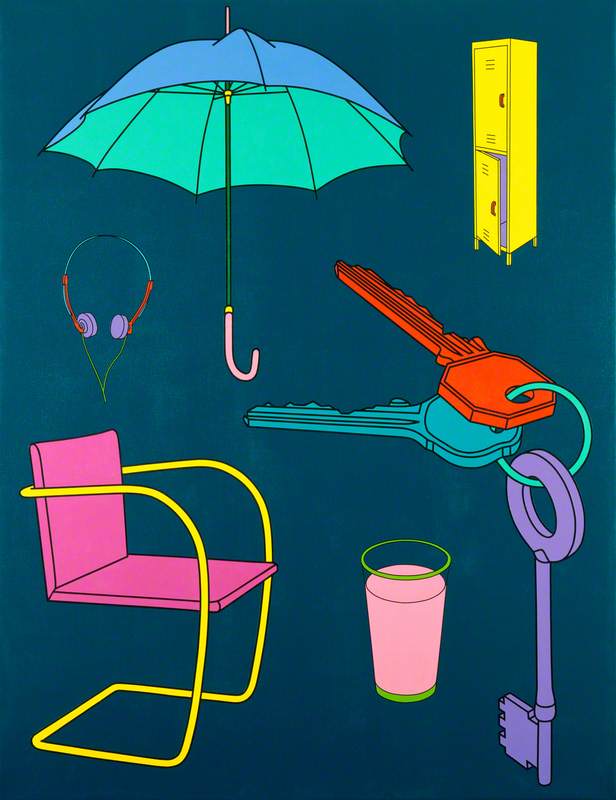

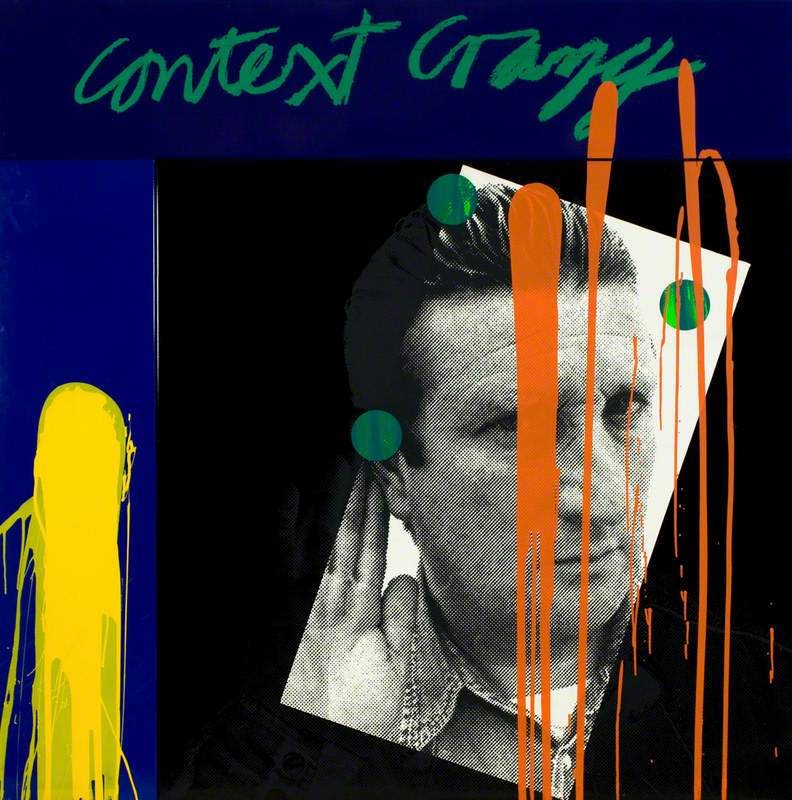

Image credit: Paul Richards

Nice Style

Bruce: I like the idea of mixing things up, high art and low art, from Bruce Nauman to Liberace. I don't like things being pigeonholed. The idea of Nice Style was to make a new context to work with. It wasn't me and my group, we were all sculptors working together. It was misunderstood by some of the art world and broken up by people trying to determine what it was.

Chris: Would you consider yourself to be a performance artist?

Bruce: No! I've never wanted to be called a performance artist. I've made action sculptures, in the same way Jackson Pollock did action paintings and Johnnie Ray was an action singer. I've used dance and posing, but I've always been a sculptor, not an artist. I don't know where the term came from, but I think it was invented in the late 1970s and ever since organisations like the Arts Council have used it because they need to put a label on everything.

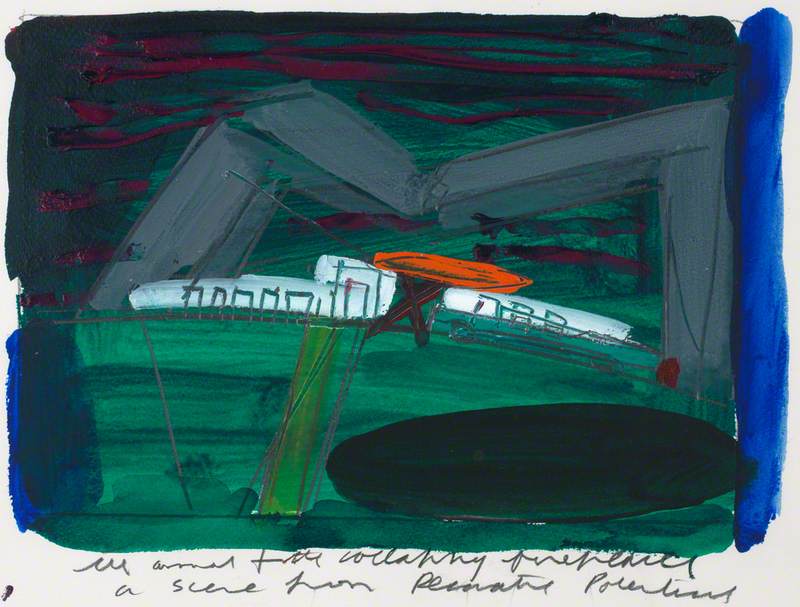

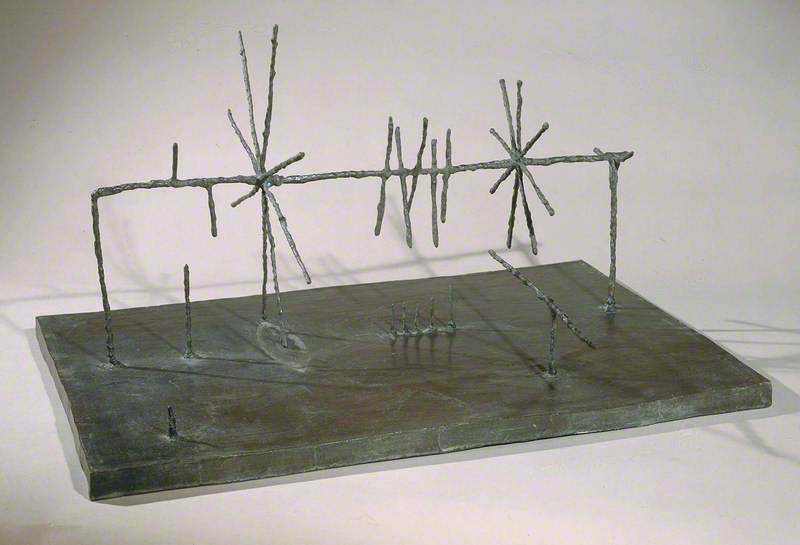

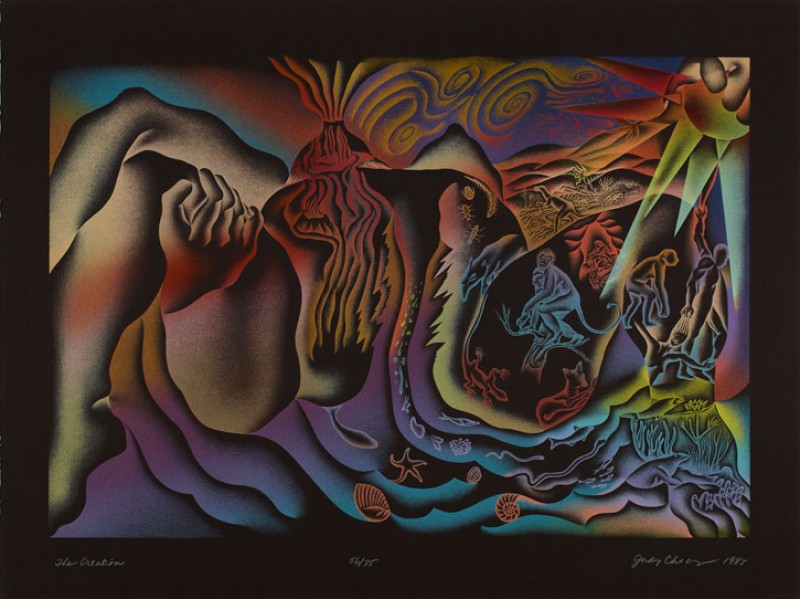

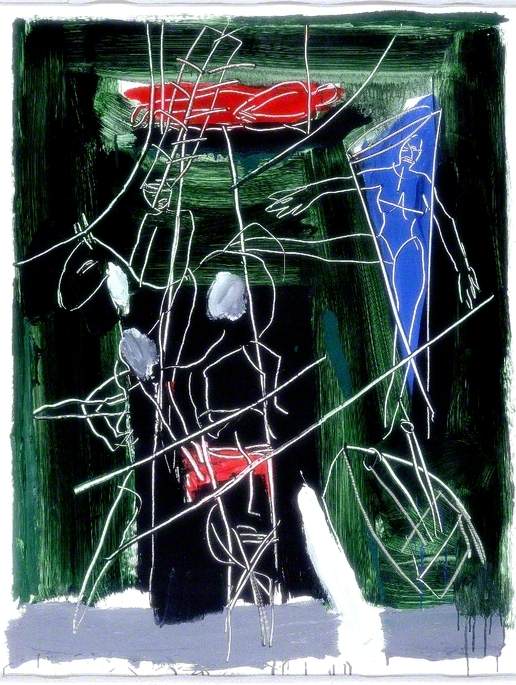

© Bruce McLean. All Rights Reserved, DACS 2025. Image credit: Laing Art Gallery

Towards a Performance, Good Manners or Physical Violence III 1985

Bruce McLean (b.1944)

Laing Art GalleryChris: How did you move from action sculpture into painting?

Bruce: After Nice Style broke up in 1974, I started making drawings with Paul Richards, another member, for a major project called 'The Masterwork' and out of that I became more interested in painting. There was a resurgence at the time, because people had got fed up with conceptual art, which I'd been one of the instigators of in Britain along with Barry, Richard and Roelof Louw. I was accused of being a charlatan and giving up on the avant-garde, but I didn't care – the work determines what I do next, I don't know what I'm going to do tomorrow.

I'm not a career artist, I'm just trying to be a sculptor. Everything I do and have done, whether it's film, dance, song, painting or drawing, is related to the notion of what sculpture might or might not be. My ambition is to make a new sculpture, something that changes people's perception of what sculpture could do, what it has done or what it might do. That's what I'm doing with my paintings at the moment.

I'm painting my ceramic sculptures of jugs, trying to correct mistakes I made at the time or do things better with paint than with firing. They're very odd, but I like them. With a bit of luck, something might come out of that.

Chris Mugan, freelance writer

The exhibition 'Black Garden Paintings' runs at Attenborough Arts Centre, Leicester, until 2nd October 2022