In the series 'Seven questions with...' Art UK speaks to some of the most exciting emerging and established artists working today.

Last year's Turner Prize was notable for several firsts: a debut appearance in the West Midlands' Herbert Art Gallery & Museum to mark Coventry's time as UK City of Culture, along with a groundbreaking shortlist of collectives and artist-run projects rather than the usual individual artists.

The winners, Array Collective, are the first to represent Northern Ireland. Since 2016, its Belfast-based activist-artists have provided mutual support and devised responses to the region's particular social and political issues.

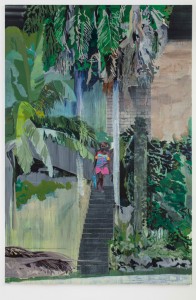

Array Collective, Pride 2019

Their work has included performances, protests and events in support of such campaigns as the decriminalisation of abortion in Northern Ireland and challenging legislative discrimination against the queer community. Recent years have seen more ambitious undertakings, including a large-scale installation created for the 2019 Jerwood Arts group exhibition 'Jerwood Collaborate!', which featured fictional characters drawn from Irish myths to reconsider contemporary anxieties, and the síbín or illegal bar built for the Turner Prize show.

Having won the award last December, the collective named after the studios where it formed was caught up in a whirlwind of art-world and media interest. Having taken a well-earned breather, Array's 11 members have agreed to answer – as a collective – questions about their background, practice and the challenges of working and living in Northern Ireland.

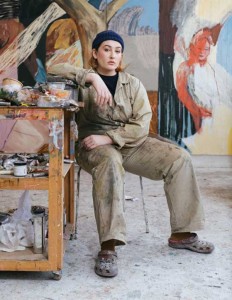

Array Collective at the Turner Prize Awards 2021

Chris Mugan: Congratulations on winning the Turner Prize! At the ceremony, Pauline Black from 2 Tone legends The Selecter handed you a cheque for £25,000. Any plans yet on how to spend this? Or how will you go about making the decision?

Array: We have no plans yet, but we have a meeting this weekend! Pre-Turner, our meetings were on an as-needed basis but now the full collective comes together weekly and we have smaller meetings as well. Some of us are hopeful about securing a new space in Belfast city centre, but even with the prize we still couldn't splash out on our own, so we will see!

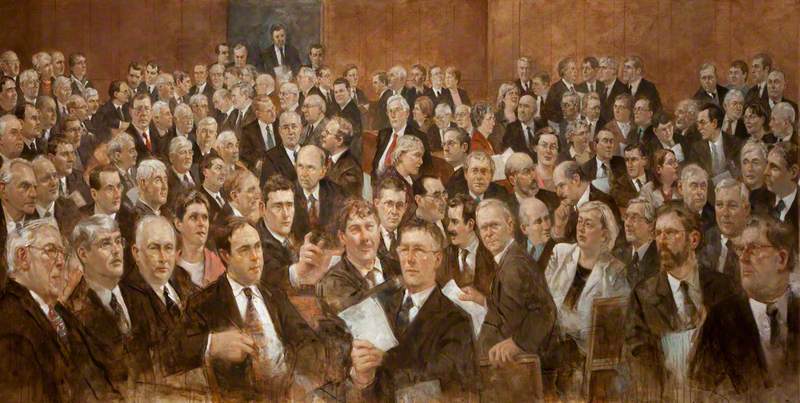

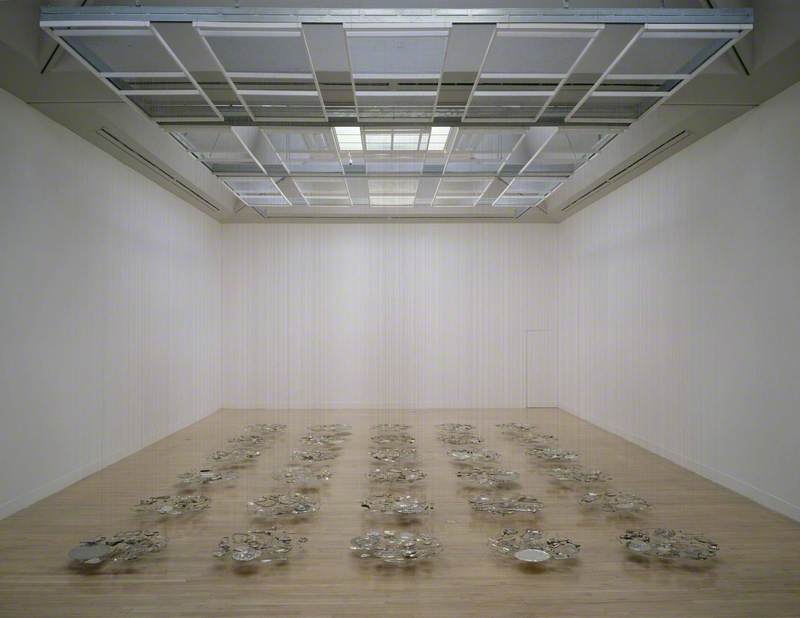

Installation view of 'Jerwood Collaborate!'

Chris: How did you come together as Array?

Array: [It comes from] the fact we were all out marching together for causes we believed in, the fact we were all friends. The studio is where six of us have physical studio space, but the collective is the larger group of artists that make things happen together.

We're from different backgrounds and places, but have made Belfast our home. We are all friends first and foremost – the collective would not have happened without these pre-existing friendships. We eat, drink and dance together.

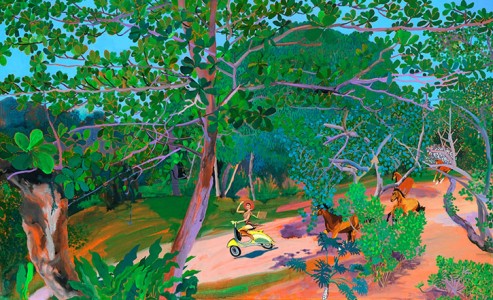

'The North is Now'

2020, public installation by Array Collective

Array started to form sporadically and organically from around 2016–2017 as queer and abortion fights were snowballing and gentrification ramping up. In 2017 we expanded and developed quite naturally into a collective due to various societal situations, the political climate and issues that were happening at the time.

Chris: How does your collaboration work in practice? How do you decide what to show together?

Array: We didn't start with a manifesto, more like a shared outlook. Then we developed how we worked together and how we made decisions when those needs arose, bringing in all of our experiences from working in the arts and heritage, community and voluntary sectors and past projects we worked on as part of other groups.

We have been able to survive doing this work because we are a collective, which means we don't all have to be 100 per cent [committed] all the time. The ebbs and flows of life outside of practice can be accommodated, such as looking after our mental health and so on.

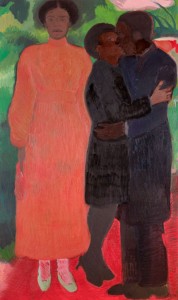

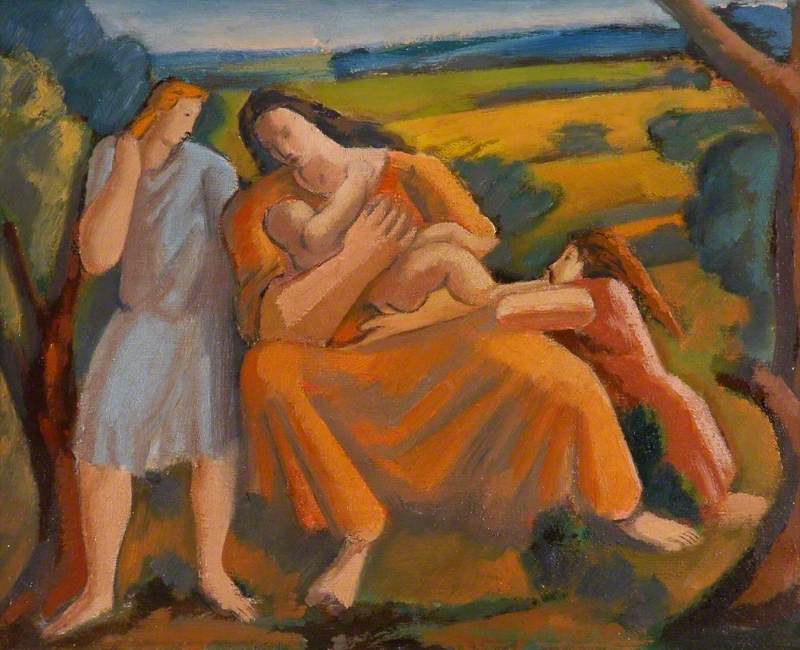

Installation view of 'The Druithaib's Ball'

2021, installation by Array Collective at the Turner Prize 2021

Chris: How far was forming the collective a response to being based in Northern Ireland? What are the challenges of working there?

Array: Identity and the legacy of the Troubles are often central to the political agreements that our country is supposed to be governed from. However, they can be reductive and restrictive and binary. They fail to include all of us and they strip us all down to impossible either/ors. The history of this place is inescapable and indeed one of our characters, called 'Long Shadow', is forever followed by a psychological shadow.

Yet all of us are living in a toxic global context where we have witnessed sharp turns to the right across many countries, especially wealthy ones with vested global interests. With that as a backdrop, it is more important than ever that our local struggles are understood as a part of a global push from the grassroots, towards greater recognition of human rights for all. At the entrance of our Turner installation, we had a series of designated days banners installed, all of which were tied to International Human Rights Days.

Installation view at the Turner Prize 2021

2021, Array Collective

Chris: What have you learnt about working as a collective? I suppose there might be practical considerations, but is there also a particular aesthetic that emerges while working in this way?

Array: One of our most often used banners is a bright pink one declaring 'Stop Ruining Everything'. It has been at Reclaim the Night, Save Cathedral Quarter, Pride, International Women's Day and as part of the last exhibition in Platform Arts Belfast before the building was shut down by developers forever. It perfectly illustrates how we adapt and reshape art into activism and vice versa.

Array Collective, International Women's Day 2019

We are proud of our dark humour, but we're only ever punching up. In his Education for Socially Engaged Art, the Mexican artist Pablo Helguera talks about the French medieval Feast of the Ass, where social hierarchies are temporarily broken through satire, celebration and chaos.

What Array tries to do is much like this carnivalesque approach to an agenda. As Helguera writes, 'not accurate representation but rather the complication of readings so that we can discover new questions'.

Chris: You are all working on solo work at the same time as Array projects. How do you balance those commitments and how do you maintain your identities as individual artists?

Array: The work we do as a collective is more explicitly political and tied to social movements than our personal practice, which for many of us is also political but in subtler ways. The social conditions of trying to be an artist making work under conditions of austerity, in a country with high levels of social deprivation and few paid opportunities for artists, means collective approaches enable us to sustain a meaningful practice, whilst also working and studying full time and with caring responsibilities.

Chris: Array is part of a small artistic community in Belfast that sounds quite self-supportive. What has your experience been as part of this and of Array itself over a tough few years?

Array: Being part of the Belfast artist-led community is sustaining – different generations of artists and different arts groups support each other across the city. This makes things possible in Belfast in the face of precarity – cycles of cuts in funding and evictions from arts spaces by private landlords. We're really grateful for this and we couldn't be artists without it. That generosity [helped] us make some of the work in [the Turner Prize] exhibition.

We support one another in many different ways. During COVID lockdowns we had online watch-alongs, yoga sessions and more. We big-up each other's individual practices and various other roles. And we enjoy each other's sense of humour.

Chris Mugan, freelance writer

You can find out more about Array Collective and upcoming projects on their website.