Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510) may not be as famous as Leonardo or Michelangelo, but no artist better encompasses the complexities and contradictions of the Italian Renaissance.

Image credit: Uffizi Gallery, Florence, public domain (source: Google Arts and Culture)

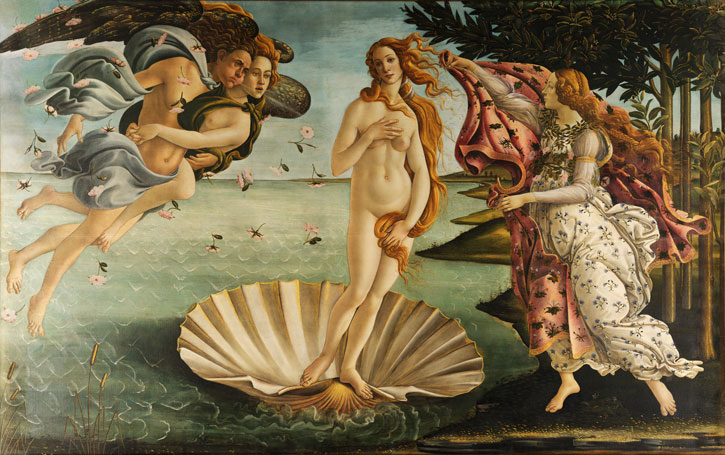

The Birth of Venus

c.1485, tempera on canvas by Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510)

Today, millions of people queue each year outside the Uffizi Galleries in Florence to see his great mythological paintings, The Birth of Venus and the Primavera.

In Botticelli's lifetime these works – made for semi-private spaces in Florentine palaces – were seen only by a handful of influential people. It is perhaps then not entirely surprising that within fifty years of his death in 1510, Botticelli had been almost completely forgotten. It took over 300 years before his pictures were accorded cult status. Loved by John Ruskin, Walter Pater and the Pre-Raphaelites, Botticelli gradually became a household name among the middle classes of Europe and America.

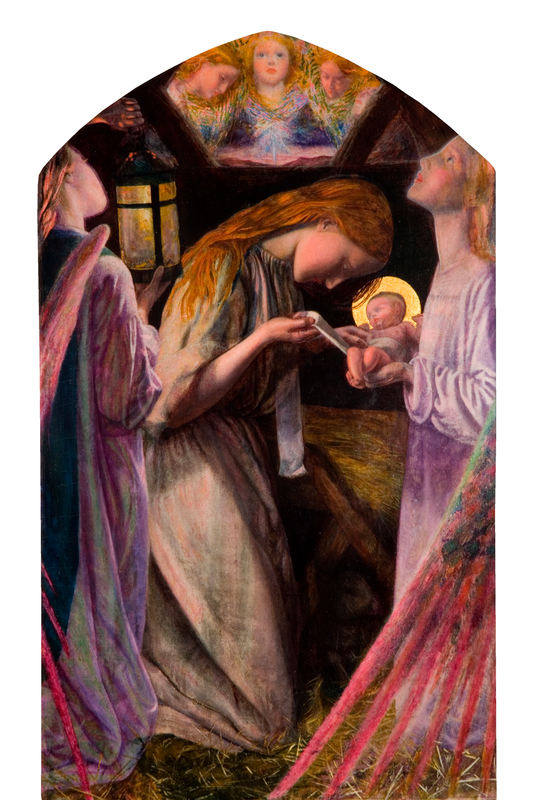

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

The Virgin Adoring the Sleeping Christ Child c.1490

Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510)

National Galleries of ScotlandSince then, his graceful, stylised and blonde Virgins and Venuses have become one of the archetypes of western female beauty, familiar and admired all over the world. Endlessly copied and reinvented by artists, trendsetters and marketeers, they nicely demonstrate that imitation is the most sincere form of flattery.

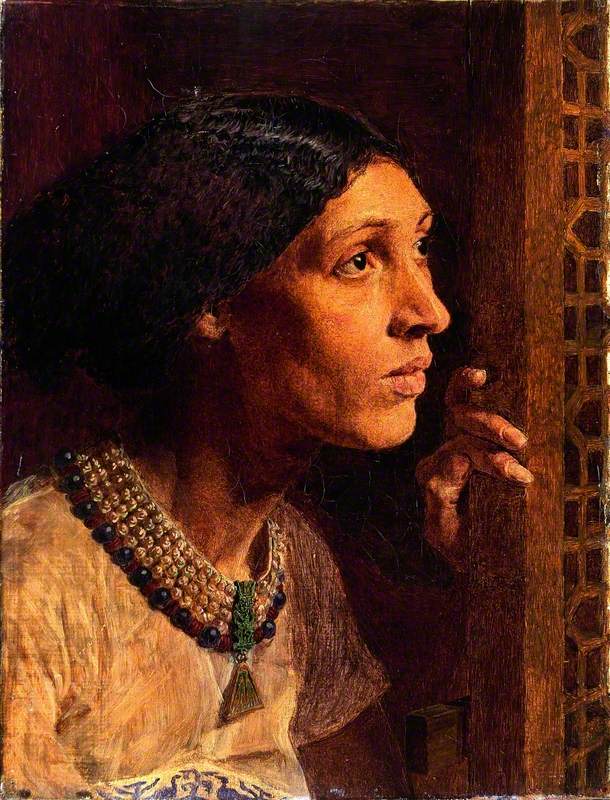

Image credit: Victoria and Albert Museum, London

Portrait of a Lady (known as Smeralda Bandinelli) 1470s

Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510)

Paintings CollectionWhat's surprising is that none of this could have been predicted during Botticelli's lifetime. He lived a quintessentially Florentine life. Born in the mid-1440s, Botticelli died a short distance away from where he was born, a stone's throw away from the river Arno, next to the church of Ognissanti where he and his family worshipped, and where he is buried. We think that he left Florentine territory only once – to travel to Rome, where he was summoned by Pope Sixtus IV to decorate the walls of his private chapel. Much of his working life was spent working for the Medici family, and their close associates.

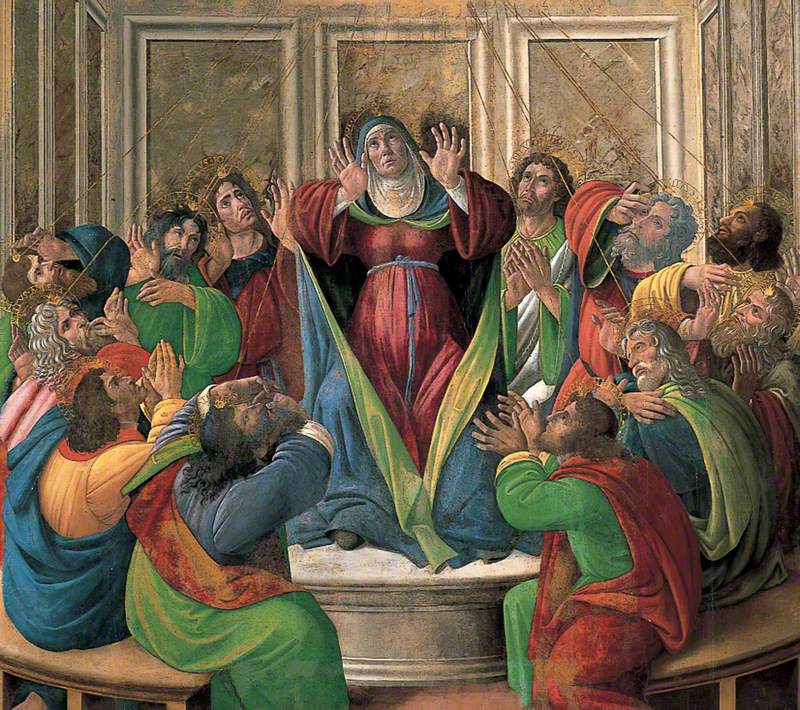

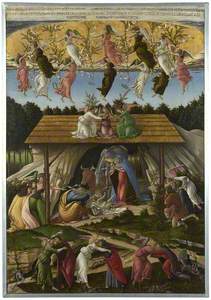

For all his Medici connections, Botticelli remained in Florence after their regime fell from power in 1494. He seems to have become an advocate of the charismatic religious reformer Girolamo Savonarola, who dominated Florence for four turbulent years. The Mystic Nativity, painted 'by I, Sandro... at the end of the year 1500 in the troubles in Italy' reflects these difficult times. Mythology was out of favour – Botticelli himself may have added some of his own paintings to the infamous 'Bonfire of the Vanities' where Florentines burnt indecent books and pictures.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

Four Scenes from the Early Life of Saint Zenobius about 1500

Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510)

The National Gallery, LondonHowever, there was still a steady market for Botticelli's work. One of the difficulties for art historians today is separating the many pictures made in Botticelli's studio, or under his influence, from those which he painted himself. The number of these works that survive today, over 500 years after Botticelli's death, suggests a career that flourished until the end of his life. So it's likely that Vasari's compelling word-picture of a decrepit, abandoned painter, dying in poverty, is some way from the truth.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

Adoration of the Kings about 1470

Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510) and Filippino Lippi (c.1457–1504)

The National Gallery, LondonThe glimpses we get of the real Botticelli suggest that life with him was riotous, sometimes rumbustious. He was renowned from his earliest years for his quick wit and hyperactivity. Even the name by which he's commonly known reflects his sense of humour, and his self-deprecation. You're not likely to call yourself Botticelli, or 'little wine barrel' – the nickname attached to the artist (born Alessandro di Mariano Filipepi) by his elder brother – unless you have a good sense of the absurd.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

Three Miracles of Saint Zenobius about 1500

Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510)

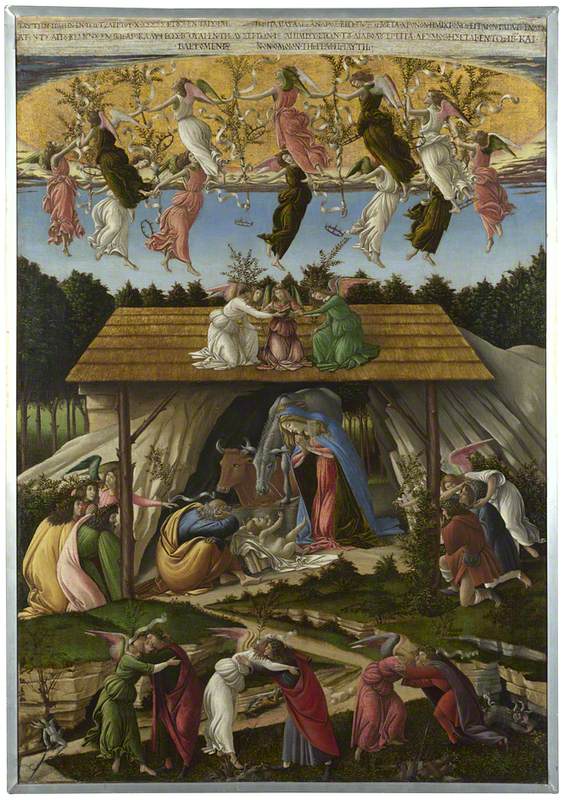

The National Gallery, LondonAnd yet, for all this, it is the sense of sublime grace and beauty, underpinned by tragedy, that draws us back to Botticelli's art. He had an unerring talent to tell a story simply, and visually. You don't need to know even a fraction of the allegories, texts and images behind the Primavera, that most complex and confusing of pictures, to understand that it's a story about spring, and about love.

Image credit: Uffizi Gallery, Florence, public domain (source: Google Art Project)

Primavera

1482, tempera on wood by Sandro Botticelli (1444/1445–1510)

Botticelli returned to fame from obscurity because his pictures have an ability to communicate to almost everyone – across the barriers of culture, of language and of time.

Caroline Campbell, Director of Collections and Research, The National Gallery, London