Monday 6th April 2020 marks the 500th anniversary of Raphael's death, in Rome, on Good Friday 1520. He's probably the artist who's had the greatest single impact on Western painting, certainly until the middle of the nineteenth century.

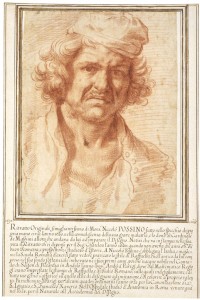

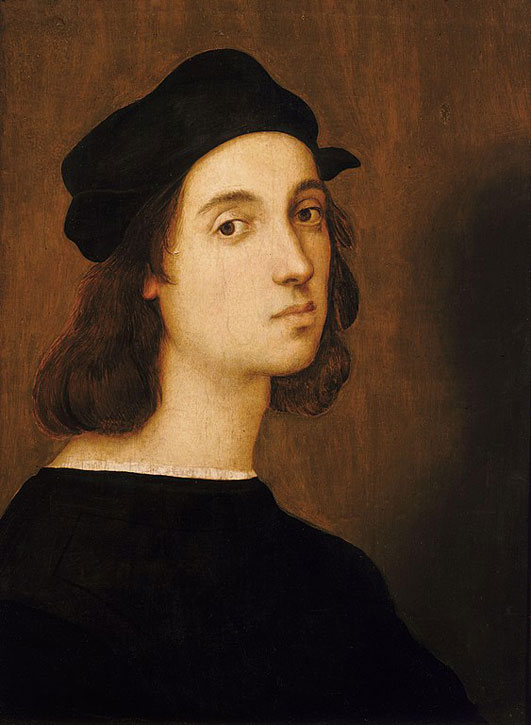

Self Portrait

1504–1506, tempera on panel by Raphael (1483–1520)

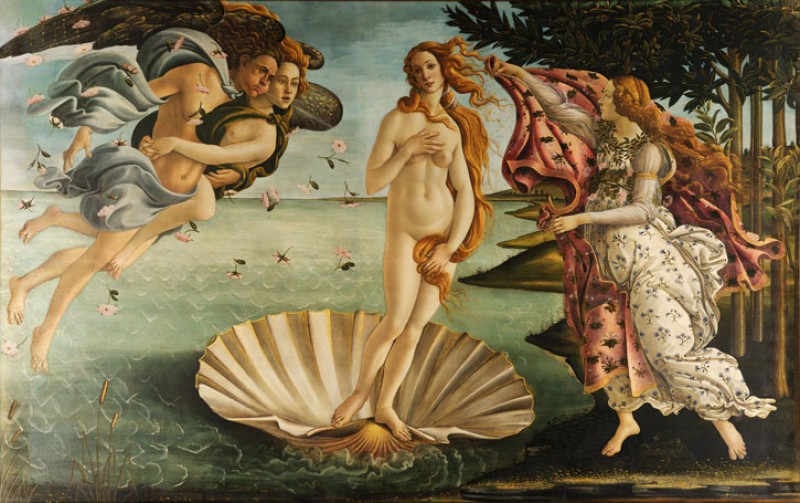

For centuries after his death, Raphael was God of the artistic pantheon. When Giorgio Vasari wrote his hugely influential Lives of the Artists in the mid-sixteenth century, he singled out three artists for aspiring painters, sculptors and architects to follow – Leonardo da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael. But most of all, Vasari (in the second and final edition of the Lives) encouraged artists to take Raphael as their model. Not only was he supremely talented and versatile – he could turn his hand to almost anything – and his technical and intellectual skills were of the highest order. No one in history has been a more talented or influential draughtsman. Just as importantly he was charming, excellent company, and adept at flattering patrons and influencers.

Raphael, or Raffaello Sanzio as his contemporaries knew him, was born in the small, elite and intellectually sophisticated city-state of Urbino in March 1483. His father, Giovanni Santi, was the court painter to the city's ruler, Duke Federico. Duke Federico's territory was so small, and so financially weak, that he hired himself out as a military commander to make ends meet. He made up for this indignity by presiding over one of the most sophisticated courts in Europe. Giovanni was at the heart of this – writing a poetic chronicle of Federico's achievements, and a further discourse about the merits of his artistic contemporaries.

It was clear from the start that Raphael's artistic talents far outmatched his father. Giovanni, to his credit, wasn't jealous. His priority was to give his superstar son every advantage in life. So, from a young age, Raphael played a leading role in his father's workshop, and, subsequently (in circumstances which still aren't entirely clear) became a close associate of the Umbrian painter Pietro Perugino. At that time Perugino was the most celebrated painter in central Italy, running workshops in Florence and Perugia, and working extensively for the Papacy. Raphael was Perugino's most talented assistant, and he fully assimilated every aspect of the older painter's style and technique.

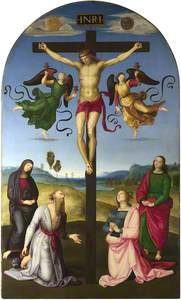

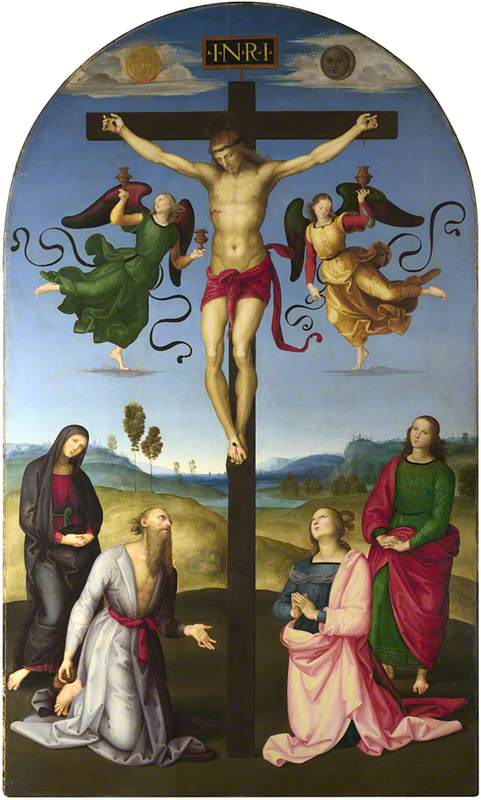

Around the year 1500, when Raphael was described as fully trained, he was also producing works as an independent artist. The Mond Crucifixion, painted c.1502–1503 for a rich merchant and banker in Città di Castello, is signed proudly by Raphael, in Latin, at the foot of the cross. But, as Vasari noted, without Raphael's signature no one would have believed that he – not Perugino – had painted it.

The Crucified Christ with the Virgin Mary, Saints and Angels (The Mond Crucifixion)

about 1502-3

Raphael (1483–1520)

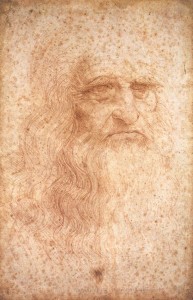

For the next few years, Raphael lived a more peripatetic life. He worked extensively in Città di Castello, in Perugia, and increasingly in Florence. Florence, of course, despite political tribulations, was one of the richest cities in Europe, and still one of the continent's greatest artistic centres. The major draw, as much as patronage, was the presence of avant-garde and innovative artists such as Michelangelo, the Dominican Fra Bartolommeo and – beyond all others – Leonardo da Vinci. Leonardo was resident in Florence from 1500 to 1506, and after Perugino, he was the largest single influence on Raphael's developing style. From Perugino, Raphael had learnt how to create perfect ideals from what he saw around him; thanks to Leonardo, he imbued his rather static compositions with a sense of dynamism. You can see this clearly in Raphael's Madonna of the Pinks.

The Madonna of the Pinks ('La Madonna dei Garofani')

about 1506-7

Raphael (1483–1520)

This tiny devotional work was painted for a private patron, probably a nun. It seems to be based on a painting by Leonardo, made about 30 years earlier. Yet the close relationship between mother and son, as the infant Christ swings towards his mother to offer her a carnation, is learnt from close study of more recent works by Leonardo, such as the Burlington House Cartoon, which Raphael may have known in Florence.

The Virgin and Child with Saint Anne and the Infant Saint John the Baptist

(The Burlington House Cartoon), c.1499–1500, charcoal & chalk on paper, mounted on canvas by Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519)

By the early sixteenth century, Florence's star was beginning to be eclipsed by a city further south: Rome, the Eternal City, since 1377 home once more to the Popes, returned from their 'Babylonian Captivity' in Avignon and the tribulations of the Church Councils. Raphael, like all men of ambition, was drawn to the honey pot of Rome – home to an aggressive, warmongering but cultured Pope, Julius II, and his court of Cardinals.

In 1508, Raphael moved to Rome, where he was to live for the rest of his short life. His first commission was to decorate semi-private spaces for the Pope and his entourage, the so-called Vatican Stanze, or rooms. This project immediately brought him into conflict with the other outstanding artist of his generation – the Florentine Michelangelo Buonarotti. Michelangelo and Raphael's rivalry dominated both their lives. It led to great personal enmity, but it undoubtedly had a positive impact on their artistic production, pushing each artist to new heights in order to triumph over the other.

The battle, at least in their lifetime, was won hands-down by Raphael. His charm and diplomacy evidently endeared him to his patrons. When Julius II died in 1513, to be replaced by Lorenzo de' Medici's son Giovanni, Pope Leo X, Raphael's ascendancy became complete. We can't, like Michelangelo, put it all down to politics. By any measure, the Stanze and the tapestries of Saint Peter and Paul that Raphael designed, to go head-to-head with Michelangelo's ceiling in the Sistine Chapel, are an incredible achievement.

Apparently effortlessly, Raphael manages to make arid intellectual debates, such as the School of Athens, or remote Biblical events, such as the Conversion of the Proconsul, exciting and dynamic.

His compositions, although carefully conceived in many drawings and plans, have a life of their own. The idealised settings, combined with the perfected naturalism of the individual figures, and a strong sense of atmosphere and emotion, are compelling.

500 years later, in very different times, Raphael's Stanze still take us from an imperfect present into a divinely created universe, where everyone and everything has its proper place. It is not surprising that his patrons, and all subsequent viewers, have found these inspiring, and – at the same time – hugely comforting. Looking at Raphael, whatever the circumstances, you feel that everything is alright with the world.

The Madonna and Child with the Infant Baptist (The Garvagh Madonna)

about 1509-10

Raphael (1483–1520)

With Raphael, the tragedy is to consider what his early death has robbed us of. While completing the Stanze, other painting projects in the Vatican (more and more the work of his very talented assistants, including Giulio Romano and Gianfrancesco Penni), and commissions for key patrons like the Sienese banker Agostino Chigi, he worked increasingly as an architect.

In 1514 he was appointed Chief Architect of St Peter's Basilica, and although much of his work was destroyed after his death, drawings give a sense of what he wanted to achieve. As Prefect of Antiquities, he lobbied for a visual survey of all monuments within Rome, and powers to prevent the destruction of ancient monuments.

He collaborated with leading printmakers so that his designs could be – as they soon were – diffused throughout Europe. So, although Raphael's legacy was long, and persists down to this day, it is hard not to wonder how much greater it would have been had he been blessed with another 37 years of life.

Caroline Campbell, Director of Collections and Research, The National Gallery, London