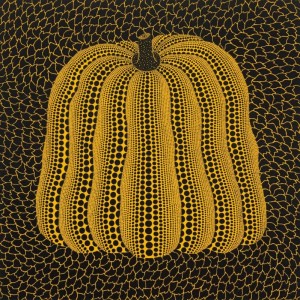

The shelves of the supermarkets may be sparse right now, but rest assured you can still feast your eyes on some of history's most delicious still lifes.

As you Google what to make out of half a red onion, a tin of baked beans and a bedraggled parsnip, let me take you back to a time when our tables were more plentiful, to an era when a bunch of white asparagus, a freshly cooked lobster and haunch of venison were commonplace. I'm not talking about Waitrose on a Friday night, but the extravagant and enticing world of seventeenth-century still life painting.

Looking at these images now they seem ostentatious and at times a little odd. Why are there so many lobsters? Why do they peel the lemons like that? Is a bowl of fruit just a bowl of fruit, or does it allude to grander themes? Art history hasn't totally decided what these images mean, but there is arguably a lost language of still lifes that leaves us all guessing.

Still Life of a Lobster, Vegetables, Fruit, and Game

1645

Adriaen van Utrecht (1599–1652)

These images were a snapshot of their time, but not in the way you might imagine; these are not larder images, these compositions intended to be fantastical and unrealistic. They are symbols of status, meaning and power. Their intended meanings are often served to us in more subtle ways – and with that in mind, I wanted to offer you a taste of some of my favourite symbolic foodstuffs.

Asparagus

Louis XIV of France dubbed asparagus the 'king of vegetables', which might be one of the many reasons this venerable vegetable appears in so many still lifes of the era.

In the Netherlands, the widely admired asparagus was associated with luxury, prosperity and abundance – its presence in Dutch still lifes thought to be symbolic of the fruits of paradise. Meanwhile, the seventeenth-century herbalist, Nicholas Culpepper, wrote that asparagus 'stirs up lust in man and woman', which is why it may have a further symbolic suggestion of virility and desire. Indeed, the French word asperge is also slang for a certain male body part...

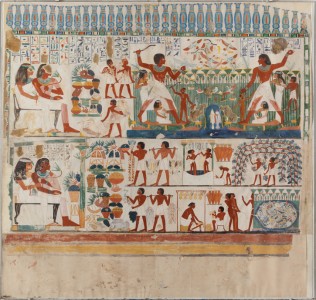

Cabbages

You'd be forgiven for thinking that a cabbage is an ordinary vegetable, but this understated icon of averageness has fascinated us since the age of the ancient Egyptians. Used in medicine and in cooking throughout the centuries, this sturdy vegetable was also recommended during the Roman era as a hangover cure, making it both an ancient licence for excess and a stoic symbol of sustenance.

This dual meaning makes it the perfect vegetable for inclusion in Nathaniel Bacon's Cookmaid with Still Life of Vegetables and Fruit, where the flamboyant bustle of leaves dominates the painting, mirroring the fabric of the figure's revealing dress – both alluding to a more delicate interior.

This sort of market scene was a popular genre in the seventeenth century, a chance for artists to hone their skills of observation and idealise the everyday. Here the humble cabbage is a symbol of beauty under the surface: it is both ostentatious and ordinary. Lewis Carroll had it right when he wrote 'Of shoes – and ships – and sealing-wax / Of cabbages – and kings'.

Lemons

The lemon has come to symbolise many opposing ideas – while it's considered a symbol of luxury, love and longevity, it's also emblematic of sourness and disappointment. The lemon is bittersweet: its beauty at odds with the sharpness within. Of all the icons in the still life scene, the lemon is the most favoured. Its appeal was both to the artist, as a chance to display their skill – and to the patron as an opportunity to demonstrate their sophisticated tastes.

If we look at a work such as Jan Davidsz de Heem's Still Life with Fruit (1650s), each curl of peel embodies a grasp of shape and perspective that only the most experienced of artisans can master.

While some say the peeled lemon may be seen as a symbol of time passing, its enduring appeal also makes sense of the Catholic tradition that links the fruit to fidelity. The art historian Mariet Westermann describes the lavish lemon as 'a sign of having arrived in society, as much as a Mercedes or a Louis Vuitton bag is today'. So next time life gives you lemons, what you should really do is paint them.

Lobsters

Like all representations of meat, game and shellfish, the lobster is most commonly thought to symbolise wealth, gluttony and temptation.

Certainly, if we look at the lobster in Simon Luttichuijs's Still Life, it seems almost remorseful, subservient yet also an audacious centrepiece. Some say the lobster is an allusion to the Resurrection, while others believe that the lobster represents unpredictability – due to its ability to crawl both forward and backward. Whatever your interpretation, it is safe to say that this crustacean has remained a powerful symbol for artists and designers, as popular now as it was then.

A classic still life motif, the lobster is also a memento mori, a symbol of both life and death. While almost every depiction of a lobster appears animated and characterful, the scarlet shell reveals that these shellfish are sadly departed – because a lobster only turns crimson after it has been cooked.

By looking for symbolism in these paintings we're seeking reason in these magnificent meals. While they certainly can suggest deeper meanings and nuanced connotations, at their core they are a visual feast, a lavish display of luxury that is intended to be consumed with our eyes.

Like the pageboy stealing a grape in Frans Snyders' Pantry Scene, we are all tempted by these displays, with their timeless allure continuing to be food for thought.

Tasha Marks, food historian, artist, and founder of AVM Curiosities