It was back in 2012 that I first met Roger Cardinal, who died on 1st November 2019. I was then engaged in writing a chronology of the East End artist Madge Gill, whom I'd been privately researching for some time, for an exhibition at the Nunnery Gallery in Bow.

Roger Cardinal (1940–2019) was an early champion of Gill's work, and a consultant on the exhibition; we were happy to compare notes. I discovered that he was the author of Outsider Art, which I had read at art school and which had struck me then – back in the 1980s – as revelatory. It was a doorway into a new world, excitingly different to the mainstream art I knew – though my high school tutor, the New Zealand painter Robert McLeod, had been at pains to stretch our curiosity beyond that of the school syllabus, bless him, and introduced us to automatism, beloved by the Surrealists.

As an enthusiast of Surrealism, Roger Cardinal wrote and taught on the creative imagination in literature and the visual arts. He was Emeritus Professor of Literary and Visual Studies at the University of Kent at Canterbury, but was perhaps best known for his work in the field of Outsider art, writing frequently on the subject, and a contributing editor for its primary journal, Raw Vision.

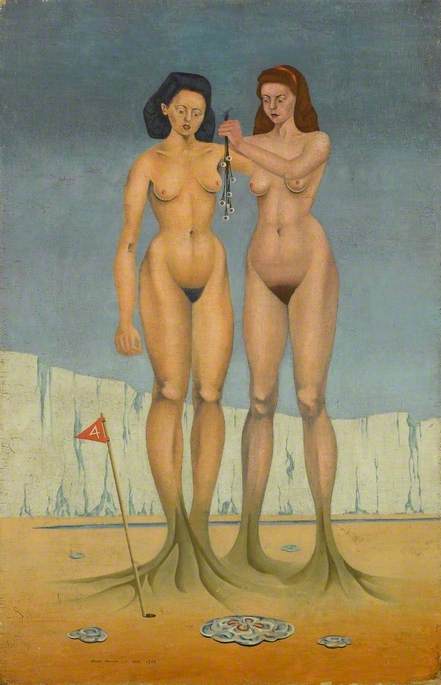

His 1970 book Surrealism: Permanent Revelation, written together with Robert Stuart Short, took a fresh approach to its subject, attempting to evoke surrealism's potential for a more 'lyrical' mode of behaviour, thinking, and seeing.

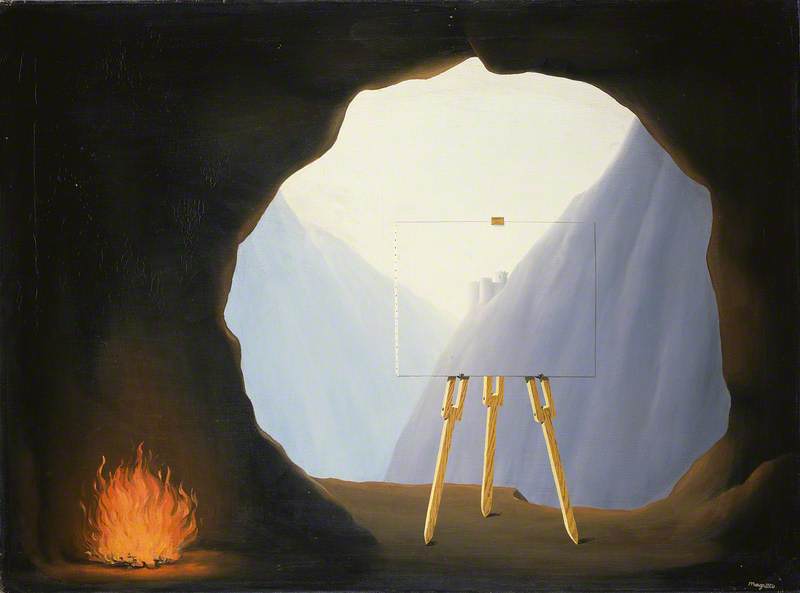

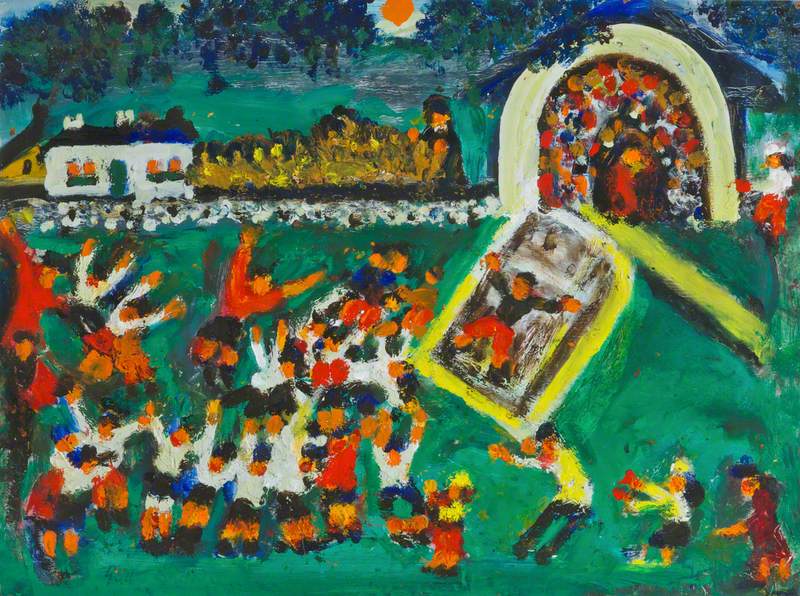

© ADAGP, Paris and DACS, London 2025. Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

Le temps menaçant (Threatening Weather) 1929

René Magritte (1898–1967)

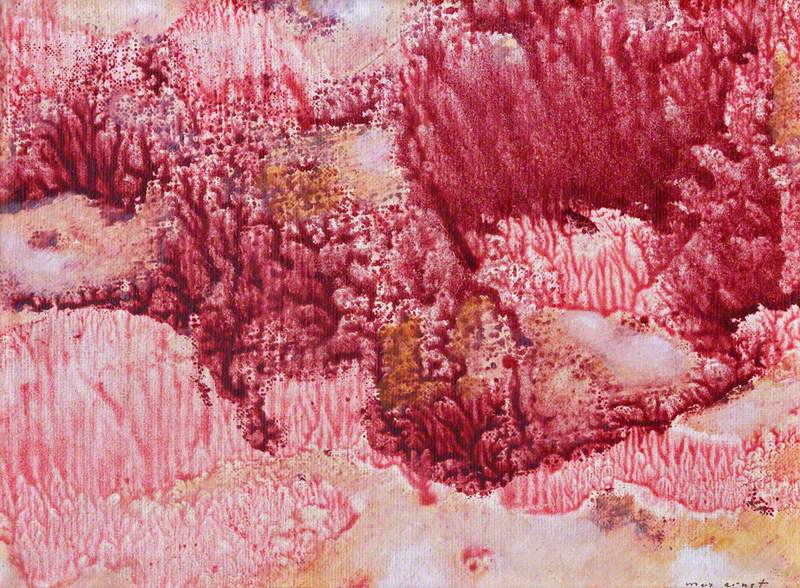

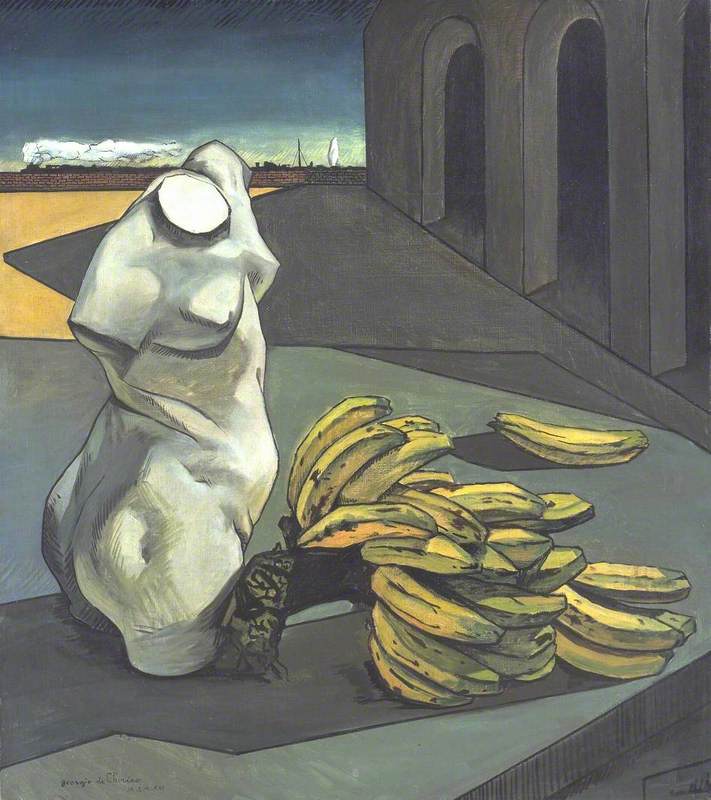

National Galleries of ScotlandUsing photographs, sketches and paintings (many in Continental collections) the authors examined the paranoic visions of Salvador Dalí, the subverted dream landscapes of Magritte, the 'chance' techniques of automatism, frottage and decalcomania of Max Ernst, and the disquieting juxtapositions of Giorgio de Chirico.

De Chirico, Cardinal observed, seemed to view life 'as a vast repository of unknowable secrets'.

Underlying his work, and indeed much Surrealist creative endeavour, is what the French poet Henri Michaux described as 'a hunger for situations of estrangement and discontinuity', perhaps seeing these as a key to unlocking these 'unknowable secrets' and so to shed some light on our everyday.

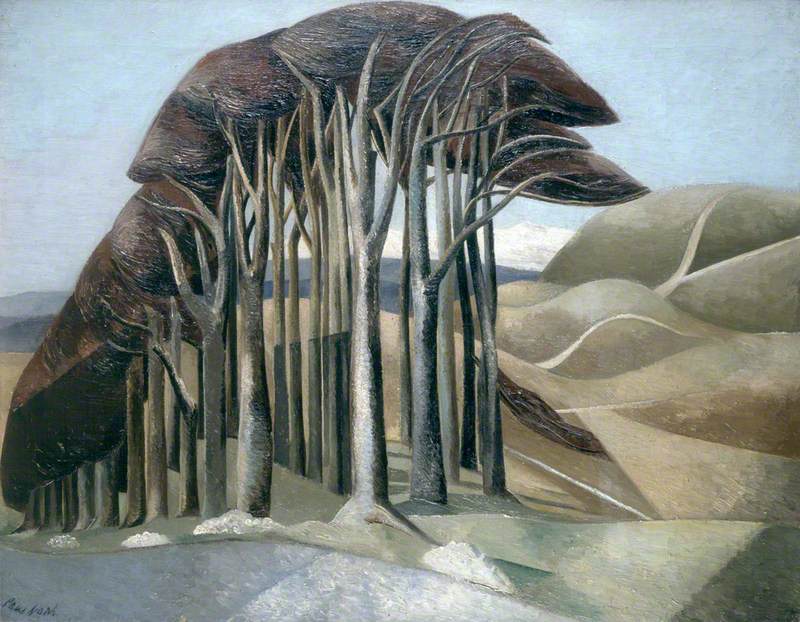

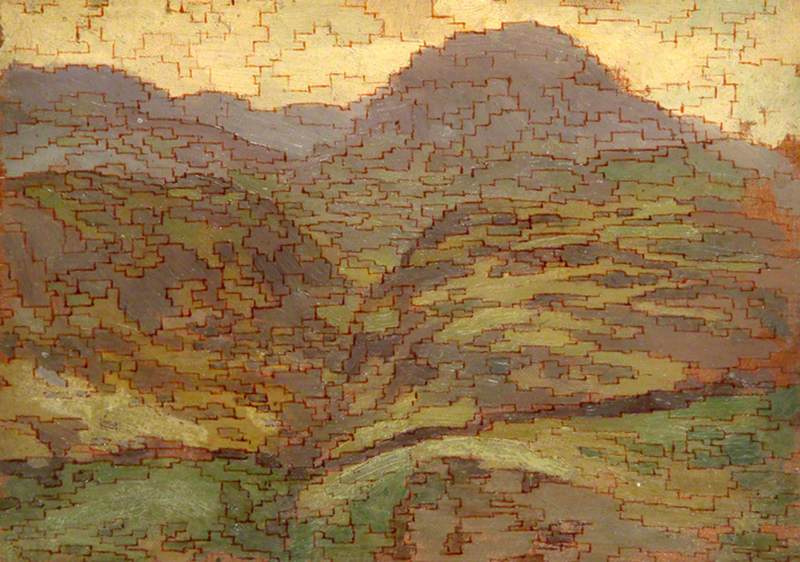

'Surrealism somehow embraces both the realist and visionary attitude by an art which at once discredits and renews the reality of ordinary perception,' Cardinal wrote. In The Landscape Vision of Paul Nash (Reaktion, 1989) he brought this understanding to his study of the English landscape painter Paul Nash.

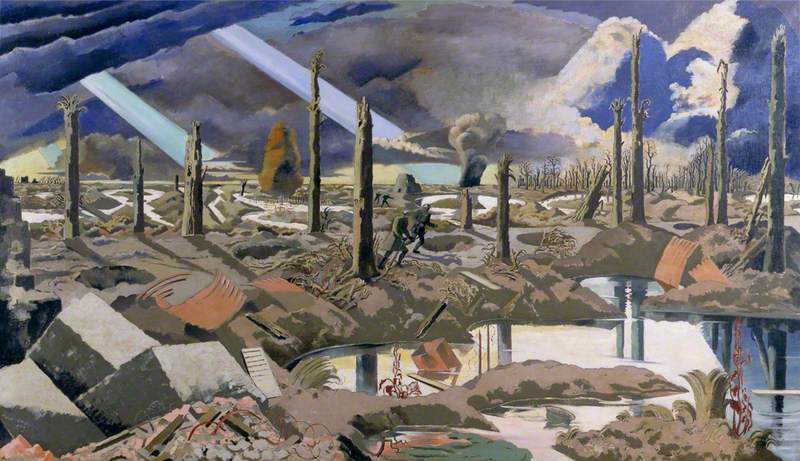

In it, he explored the range of Nash's work, from his enchanting Bird Garden at Iver Heath (1911) to the devastated landscapes of his Menin Road of the First World War and his Totes Meer of the Second.

In this latter work, the wreckage of a downed aircraft resembles a lifeless, metallic Dead Sea; in both, in their separate ways, the unforgiving pattern of war transforms an ostensibly 'straight' view of landscape into a surreal version of itself. Cardinal noted Nash's taste for sites of disaster, 'able to discern in their ruinous aspect a potential for poetic renewal, evinced in the suggestiveness of their monstrous, stricken shapes.'

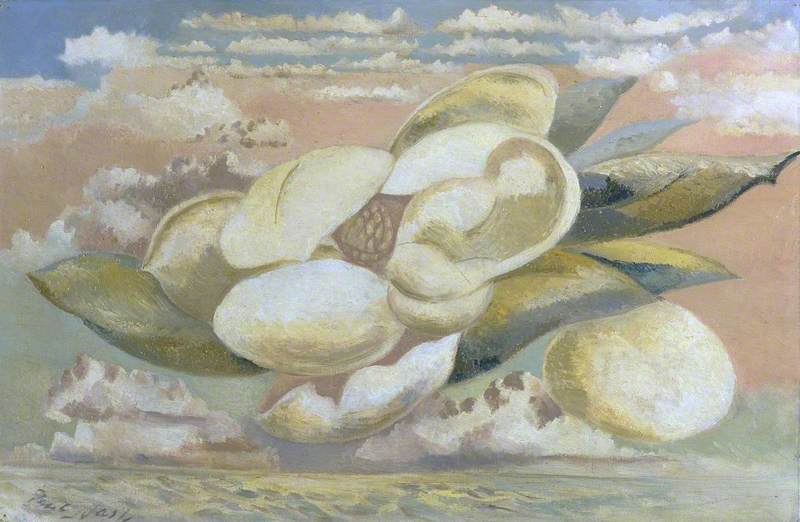

This surreal poetic element is present in Nash's later oils, like his Landscape of the Vernal Equinox (III), a contemplation of the Wittenham Clumps, and Flight of the Magnolia, both 1944.

'It is evident that Nash, in the waning months of his life, felt impelled to establish images of reconciliation in which the polar values of the sun and the moon, of life and death, of masculine vigour and feminine sanctuary, are fastened in dream-like apposition... Both real and unreal, lit up and mysterious, the magical landscape hovers before us, as we before it, suspended in a zone of pleasurable confusion wherein the familiar brushes against the unfamiliar, and the intangible floats silently into our embrace.'

Nash, Cardinal concluded, was a painter of 'the real', but one who cast a light on the unperceived within that reality: 'When Nash evokes 'hidden landscapes'... he is pointing not to a realm beyond our mortal orbit, but to 'the world that lies, visibly, about us.'

This wavering between inner and outer, of unperceived and hidden realities, this Surrealistic and, yes, potentially redemptive element, is, one senses, what drew Roger Cardinal to Nash, to the Surrealists, and in turn to the so-called 'Outsiders' – that incoherent grouping of disparate artists with which Roger was to become particularly associated. In 1970 he published Outsider Art, an exposition of the art made by, variously, the artistically untutored, the mentally unstable, the socially excluded – a collation of un-doings and understandings quite different from the aesthetic and social norm.

His book, which coined the English term 'Outsider art' (something Roger himself was never entirely at ease with) introduced to English-speaking audiences this 'new' type of art, one largely overlooked here in Britain, until very recently.

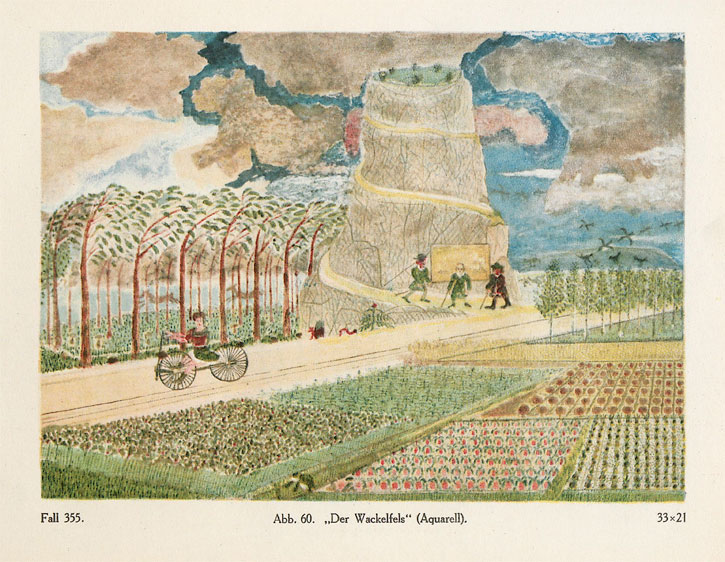

Image credit: Heidelberg University Library, https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/prinzhorn1922/0124

Case 355, fig. 60, 'The rocking rock'

watercolour, from Hans Prinzhorn's 'Bildnerei der Geisteskranken', 1922

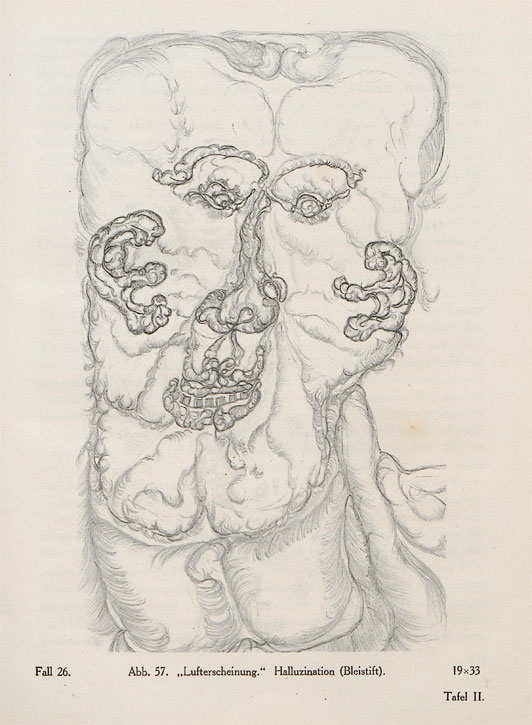

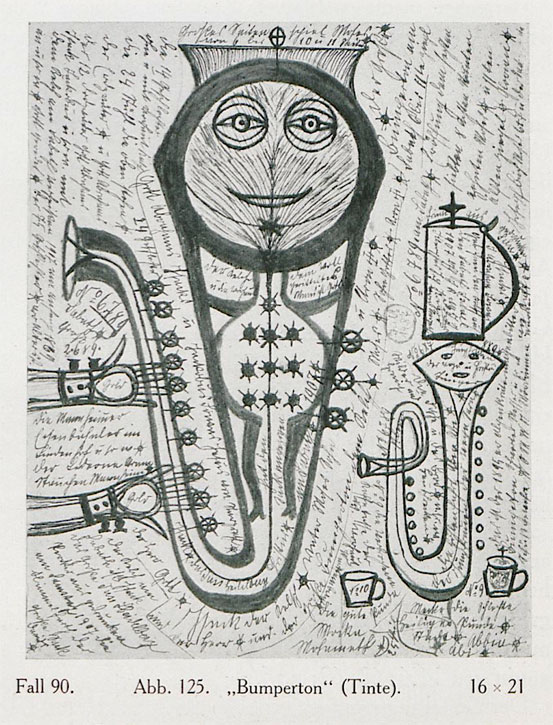

It came to public attention as a 'thing' with the publication in 1922 of Artistry of the Mentally Ill, an exposition of artworks made by patients and collected by the German psychiatrist and art historian Hans Prinzhorn at his asylum in Heidelberg.

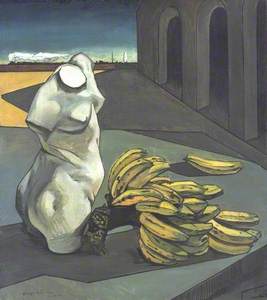

Image credit: Heidelberg University Library, https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/prinzhorn1922/0124

Case 26, fig. 57, 'Air apparition, hallucination'

pencil, from Hans Prinzhorn's 'Bildnerei der Geisteskranken', 1922

This fascinating landmark study attracted the attention not only of those in the developing field of psychiatry, but also from the art world.

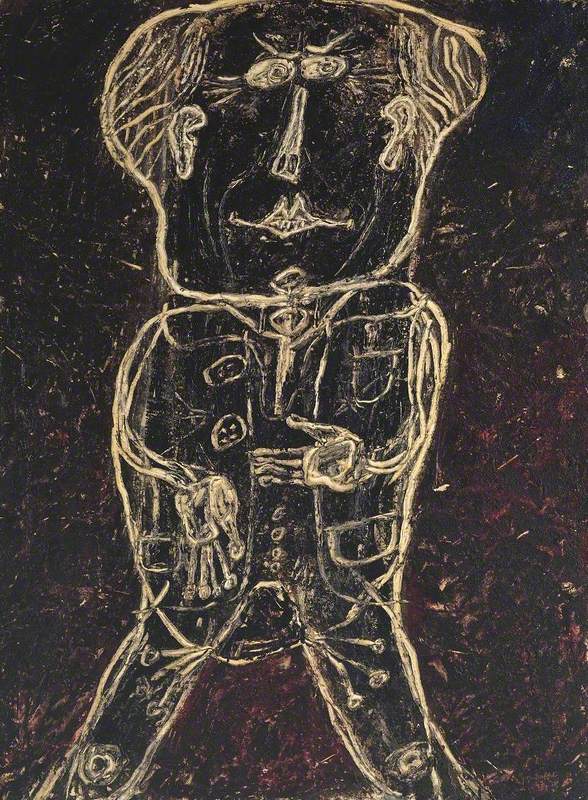

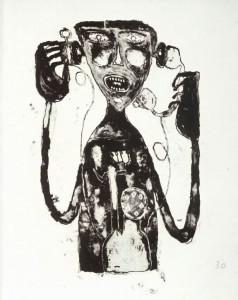

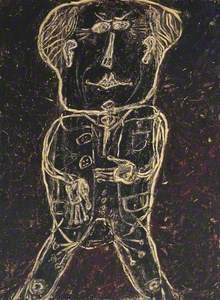

Image credit: Heidelberg University Library, https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/prinzhorn1922/0124

Case 90, fig. 125, 'Bumperton'

ink, from Hans Prinzhorn's 'Bildnerei der Geisteskranken', 1922

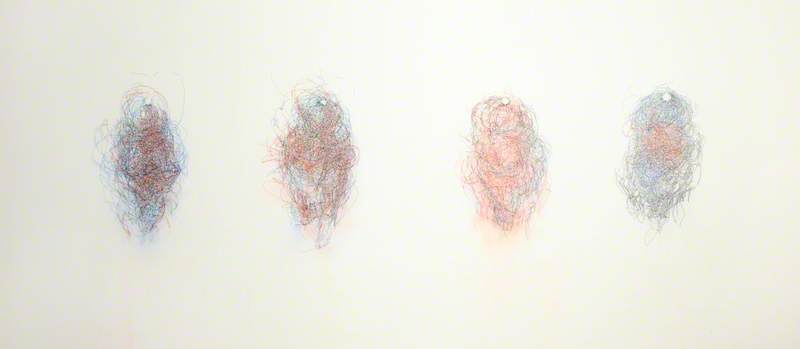

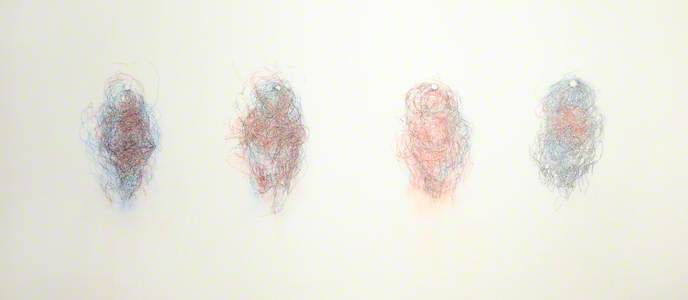

Image credit: Heidelberg University Library, https://digi.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/diglit/prinzhorn1922/0124

Case 450, fig. 74, 'Decorative symbolic drawing'

coloured pencil, from Hans Prinzhorn's 'Bildnerei der Geisteskranken', 1922

In particular, the artist and polymath Jean Dubuffet, who became an early enthusiast of what he termed 'art brut' (raw art), displaying his own rapidly expanding collection in his studio in Paris and later, more permanently, in Lausanne (Collection de l'Art Brut). Dubuffet had rejected his own academic training, dismissive of what he saw as its stifling conventions, and revelled in the incidental, spontaneous, 'raw' nature of art brut, so emotionally charged and open to aesthetic accidents (much like Max Ernst's 'chance' works). This in turn directly affected the painter's own work when he returned to painting, around the time of his 1947 portrait of his friend Henri Michaux.

In Outsider Art, Cardinal named and provided biographical context for many of these artists, reproducing 'Case 450' (above) which he identified as by Adolf Wölfli, and its title as Saint Adolfe-Grand-Grand-Godfather, dated 1915. But he extended this discussion more generally beyond Prinzhorn's collection, to other artists who shared some common traits, including three British artists: the Glaswegian Scottie Wilson, and south and east Londoners Gilbert Robert Arthur Price and Madge Gill.

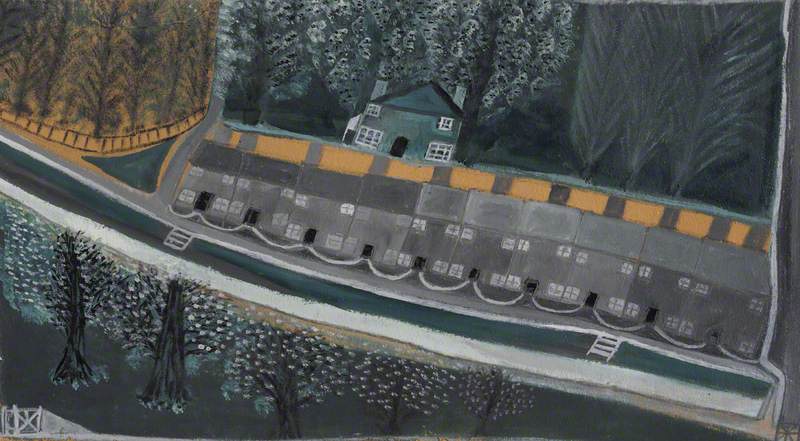

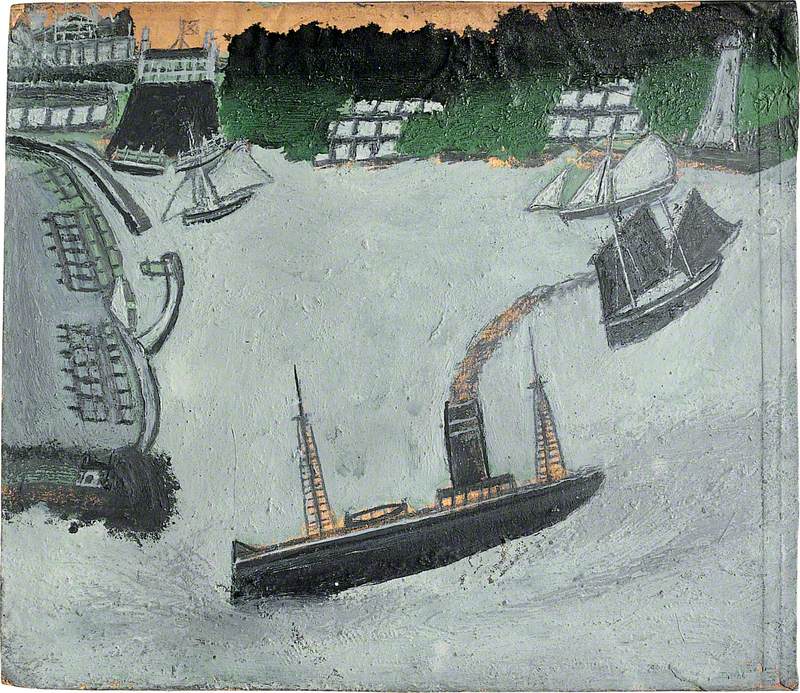

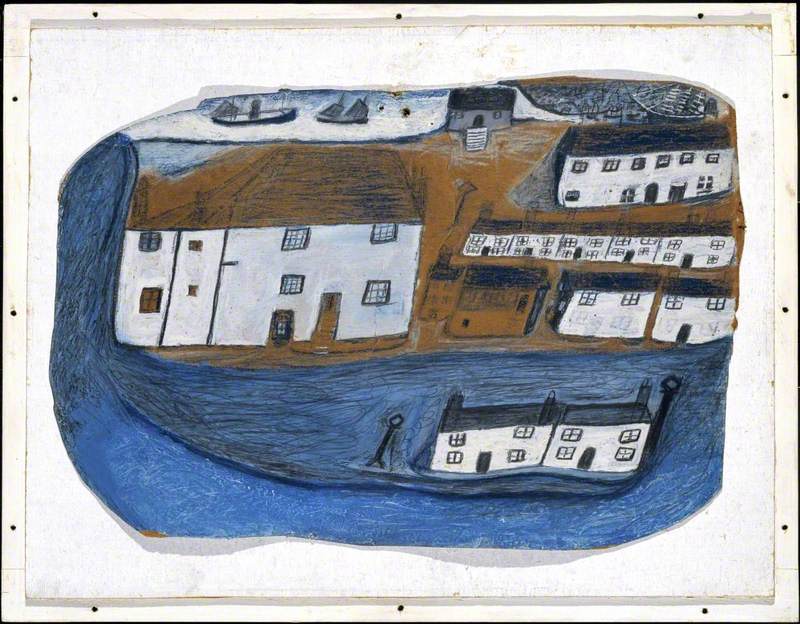

In Primitive Painters (Thames & Hudson, 1978) Cardinal took these considerations of 'illegitimate' art wider – to a discussion of folk art, much of it American. Here too British collections have lagged behind Europe and America in embracing this untutored art, but the book included a few from British collections: Henry de Valcourt Kip's quaint Attacked by Bears (c.1850) and the customs officer Henri Rousseau's quietly enigmatic Toll Gate (1888–1892), as well as works by the Cornish painter Alfred Wallis such as his Penzance Harbour (1920s–1940s).

'Unity is a preconception,' Henri Michaux wrote. Preconceptions, of idea and composition, as we have come to know them through the cultivated traditions of western art, is often absent in the work of the so-called Outsiders, the visionary, folk or primitive artists, and perhaps one of the linking aspects in this disparate 'group'.

One gets a sense of this with the naïve painter Alfred Wallis, for example, that he paints as he goes, much as a child does, starting at one end of the paper and following along the brush where it takes him, tongue poked at the corner of his mouth to aid the concentration. The 'inspired' artist Madge Gill, approached her huge calicos in similar piecemeal fashion, working on a roller contraption rigged up by her son Laurie in the drawing-room of their Plashet Grove house – able to see just a small section at a time.

Both artists clearly gave over freely to what popular psychology likes to call 'flow' – that relaxing into the creative process whereby the created object, be it artwork, novel, dance or musical competition – carries the creator away, often with little sense of controlling the process. But their lack of a compositional intent is not to deny an eventual unity – Gill was skilful enough for her compositions, their ends unseen, to come together extraordinarily well when viewed overall on completion.

Wallis, much of whose work is on display in the delightful Kettle's Yard in Cambridge, was familiar enough through his experience as a mariner with the merchant navy, and then as a fisherman, to understand almost 'innately' how ships and harbours operate. Such almost instinctive knowledge reminds one of the body knowledge evident in the palaeolithic paintings of Altamira and elsewhere.

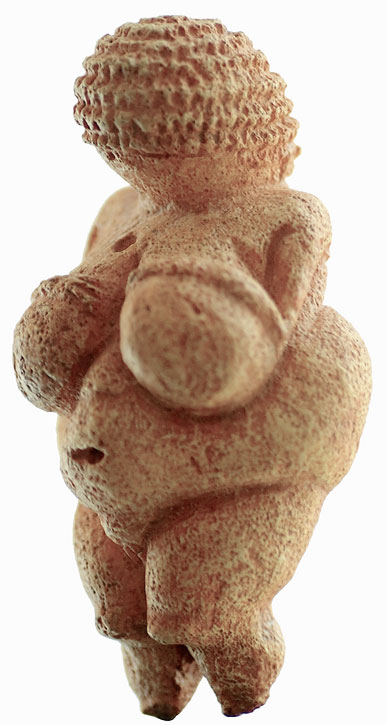

An acute sense of 'body knowledge' is, in fact, to be found in much naive, primitive and 'Outsider' art. The Stone Age sculptor of the so-called Willendorf Venus, made around 30,000 to 25,000 years ago, understood precisely how the folds of flesh sit against each other, the weight of breasts against the belly, the mass of high haunches, the texture of corn-row braids.

Image credit: Matthias Kabel, GFDL and CC BY-SA 3.0 (source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Venus of Willendorf

c.28,000–25,0000 BC, oolitic limestone by unknown artist. Naturhistorisches Museum, Vienna, Austria

One looks and at the same time one feels the sculpture. The sculpture becomes the thing, votive, a totem – who knows? But the transformation is one of primitive magic, and one that even after some thirty-thousand odd years still continues to exert a fascination.

With much Outsider art, there is a sense of 'pent-up-ness', where the energy of emotion and of intention translates onto paper or canvas in an intense physicality: densely overworked entire surface coverage (seen in the artworks of Madge Gill and 'case 90'), short sharp brutal marks, long linear swirls. With their mark-making the creator is magic-making – creating an alternate world, one often galaxies away from the theoretical approach of much post-Renaissance mainstream art, and in particular, as Dubuffet found, of that Classical vision promoted by the academies. Naïve, primitive, Outsider – what you will – is an art of process, a channelling of emotion, of magic, of incantation, of body-knowledge, of play. It is where, very often, Picasso was coming from, in his playful magical transformations.

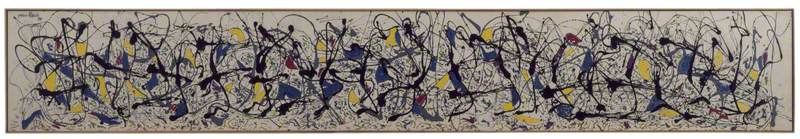

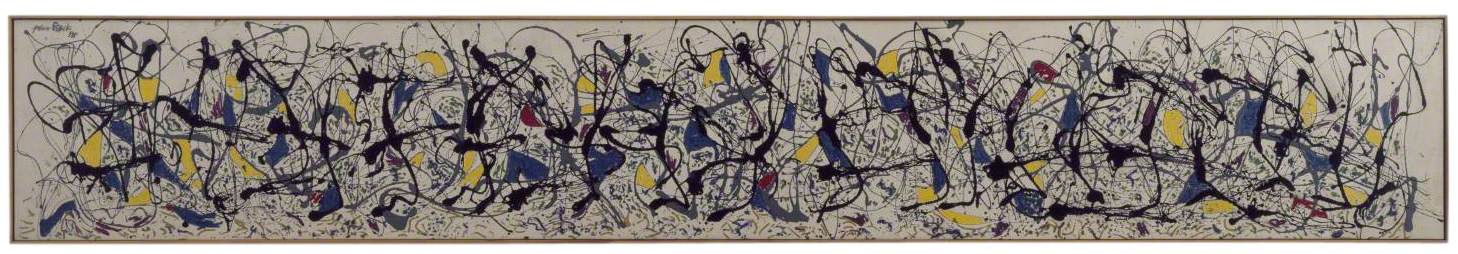

It is where, at times, Jackson Pollock coming from, with his Summertime rhythms.

It is about feeling one's way through the media and translating emotion, preoccupation and intent, into marks on a surface: it is the inverse of vanishing-point perspectives, of reductive aesthetics and academic technical skill.

Writing in 1999 Roger Cardinal described the poet Henri Michaux as wanting 'to avoid being pinned down to a single role in life', surmising that 'perhaps one isn't meant to be a single self... Michaux defines his vocation in terms of a refusal of antecedents, and a hunger for situations of estrangement and discontinuity'. Perhaps the same might be said of Roger himself, as a champion of the unprecedented, the independent in art. His take on the creative imagination will be missed.

Sara Ayad, independent art researcher