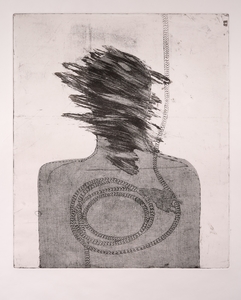

How do I look? No, really. How do I look? I don't mean tired and dishevelled, or youthful and remarkably handsome, or however I might appear to most people or my mother. I'm simply wondering if you might have a sense of – an insight into – how I might see. That is, how I might look at – and consequently select, process and interpret – things that are in this world. And then, more to the point, how do you look?

Plus que les yeux pour pleurer

2014

Flore Gardner (b.1975)

This text provides a reflection on visual literacy. As a creative exercise (which you might wish to try too), I will write 800 words or so, and then, once completed, select artworks from the Art UK online collection to accompany each paragraph. There will be no retrospective editing of the text to make reference to the pictures (although you might wish to click the artworks to find out more), and I'm not writing with any prospective artworks in mind.

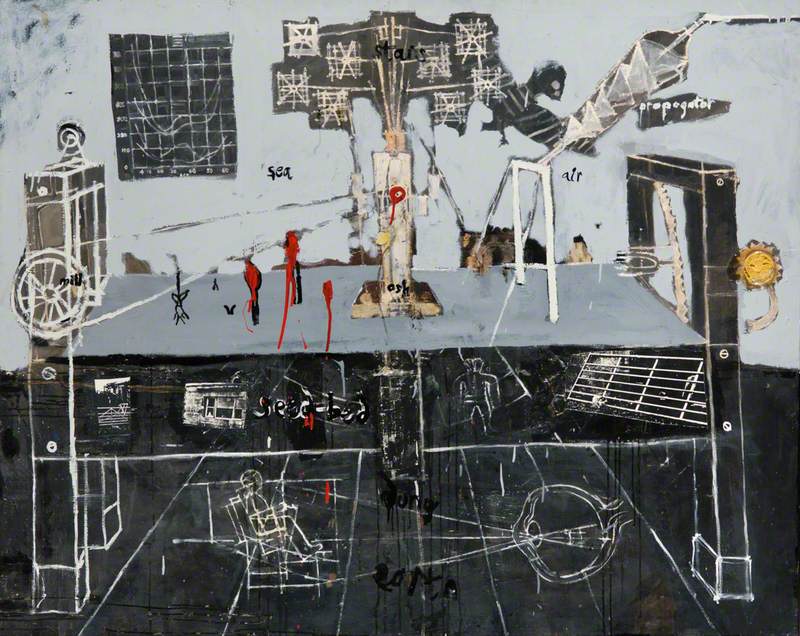

Mostly, I'm interested in how images (without explanation) might illustrate, enrich, emphasise or complicate an encounter, including this reflection, be it by chance or design. So, as you venture on, you might well ask: why am I encountering this image at this time? What is this image leading me towards (or away from)? Is this image helping or hindering me or others? These are important questions, and not just for now. These questions are increasingly pertinent for the complicated and highly visual world we inhabit. Best to keep them close.

Simply put, visual literacy is our capacity to make sense of visual information. It is comparable to learning to read, understand and make use of a complex language. As an art teacher and creative practitioner, my viewpoint on visual literacy has been sharpened. However, our ability to observe and make sense of what we see is initially formed and continually framed by wider forces. Which is not to say that images can't be conjured, applied or appreciated – felt, even – in illogical, ambiguous or inexplicable ways.

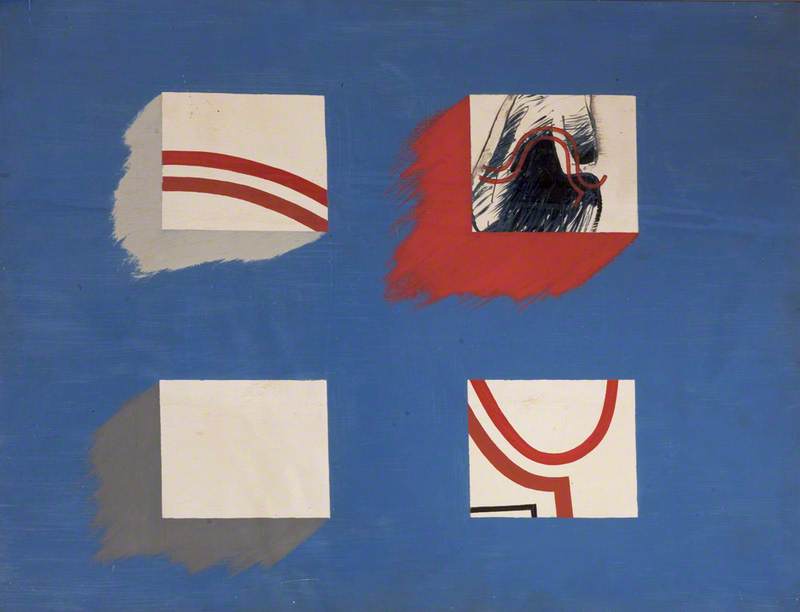

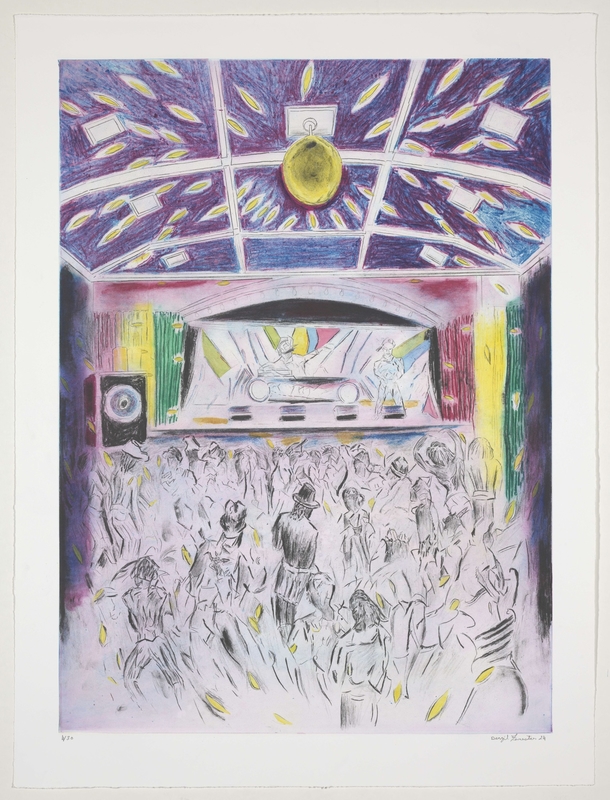

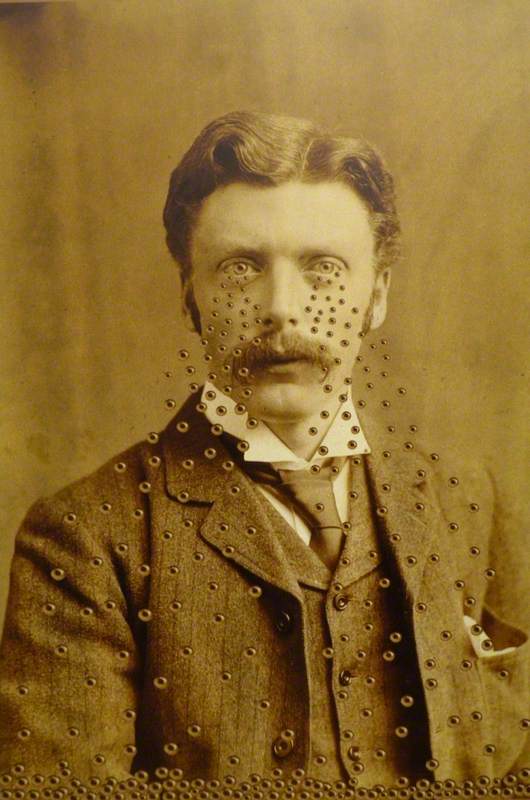

Time, histories, childhoods, chance, politics, perspectives, ethics and optics (for example) all influence our visual literacy. These and numerous other determinants might be imagined as sensitive dials and slider buttons upon a unique processor-mixer desk within our brains – a complex operating system continually at work, adapting to what we see with varying degrees of focus, fade and resonance. And if you can conjure that image, then that's also your visual literacy at work, albeit extracting from your memory bank rather than the world before you.

When it comes to deciphering or applying any language, our understanding of what we 'read', hear or set out to say – in words or pictures – is shaped by experience and education. Directly and indirectly, and for good or bad, we learn to construe and communicate with variable levels of efficiency and power. But images themselves hold no inherent meaning or power. To my teacher-mind, this is an inviting yet troublesome truth. Debatably, we might label this a 'Threshold Concept' – which could be described as a portal (of sorts) leading towards 'transformative knowledge'. But proceed with caution: Threshold Concepts can destabilise your existing convictions and shift the way that you think and see.

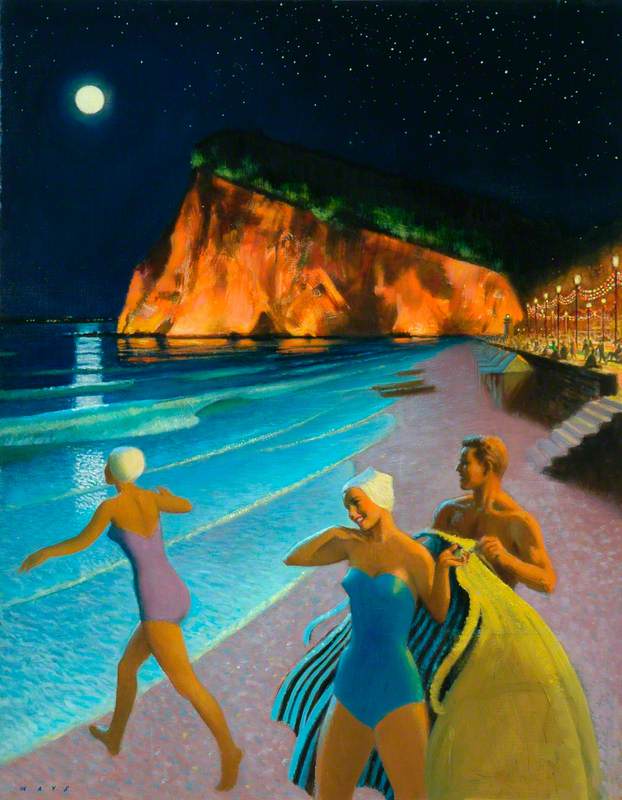

Teignmouth

(British Railways poster artwork) 1957

Douglas Lionel Mays (1900–1991)

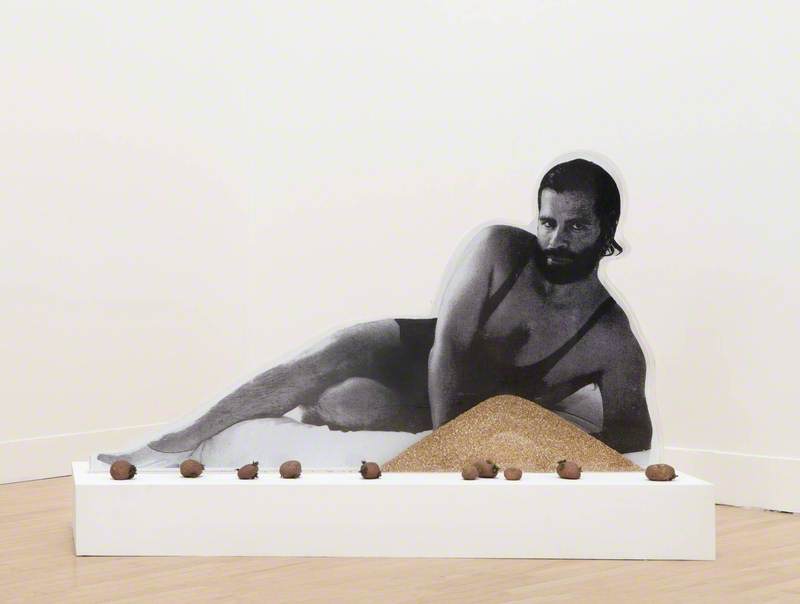

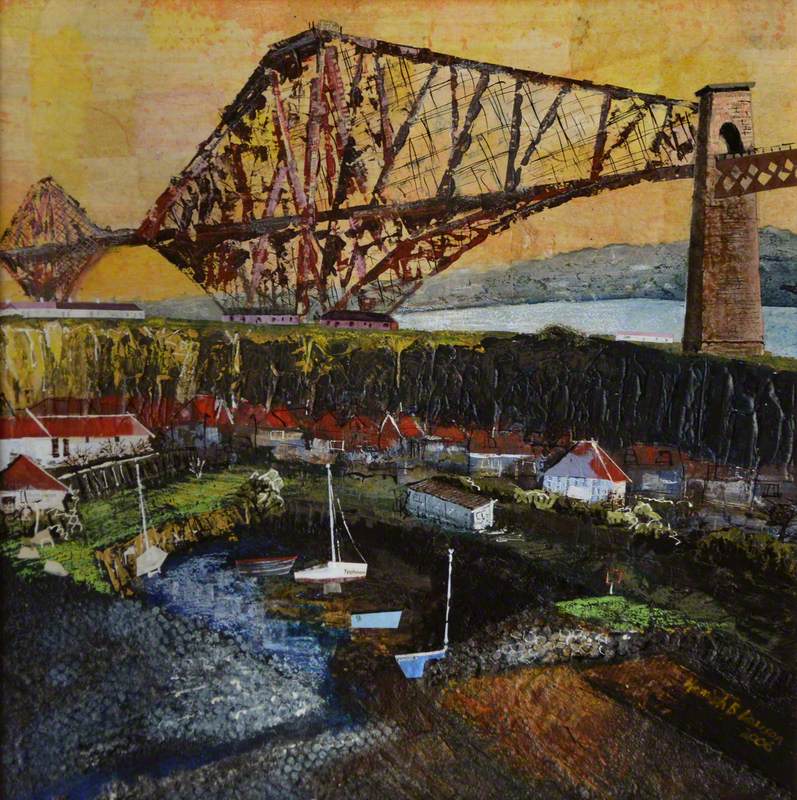

The power of an image – be it a photograph, drawing, painting, advertisement, AI-generated or whatever – does not exist within its material properties (its paper, graphite, paint or sub-pixel intensities, for example). Nor does an image's potency reside in its visual or formal elements, such as its lines, shapes or colours – or any marks that an artist or entity might make. The arrangement of these elements is often referred to as the 'design' or 'composition', but you'll find no inherent force embedded there, either. Even the subject matter of an image holds no power or meaning, be it easily recognisable (for example, as a tree, cat or potato), entirely abstract, or anything in-between.

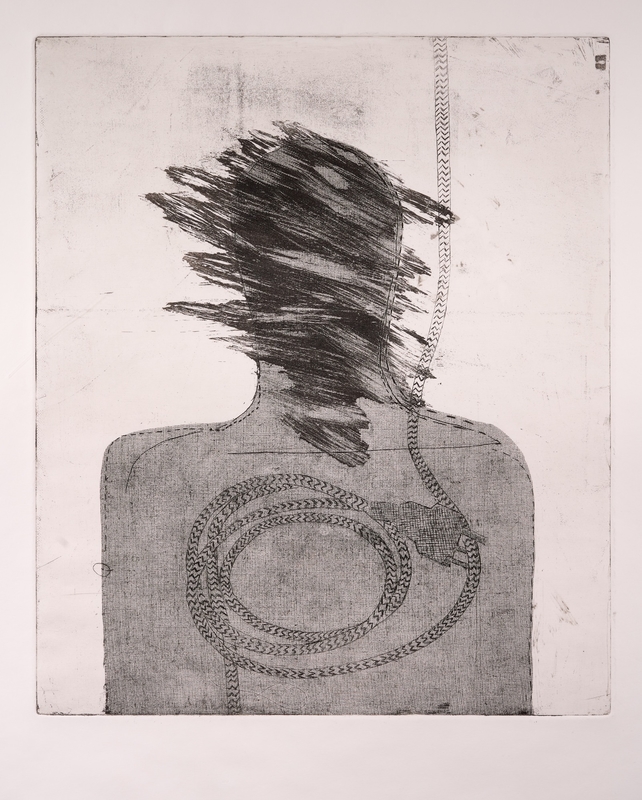

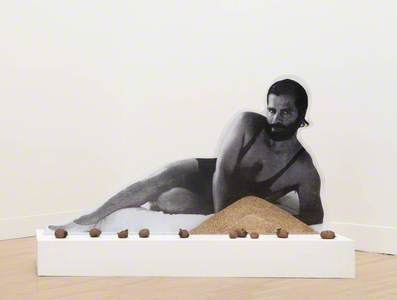

However, all these components add up. Potential is generated and possibilities arise when images are formed. Representations, illusions, messages, pictures, posters, signs or symbols are words we might also use for images. But their dormant and yet-to-be-determined power is only ignited via the act of looking. At this point, image-power can take hold rapidly, if not always reliably. Our capability to recognise, associate, interpret, sense or connect in this moment is essential to the life and influence of an image. And here lies The Superpower of Looking. By nurturing our visual literacy, we enhance our capacity to process and unpick – to question and make sense of what we see.

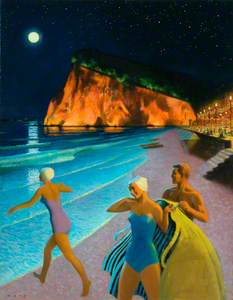

At a glance, and on closer study, images can make us feel, think, connect and (re)act. The challenge, as I see it – to return to how I look, and perhaps for you too – is to not relinquish or underestimate the power at play, but to remain alert: to be both welcoming and positively suspicious of images. And as an educator and image-maker, to harness the wonders of images – and promote the benefits of visual literacy – as a powerful force for good.

Chris Francis, arts educator and co-founder of ArtPedagogy and PhotoPedagogy