'When I was contacted by Tate Britain's director, Alex Farquharson, to take on the Duveen Galleries,' says Hew Locke, 'my first response was: "Are you kidding?" I know this space very well and it felt wonderful to imagine creating an installation for it. Then I started to feel a little overwhelmed... How to fill in such a space, such a neo-classical standard?'

Hew Locke's 'The Procession' at Tate Britain

But the Guyanese-British artist didn't need to worry. The impact of his installation, The Procession, was as profound as well-deserved. We talk just after the opening on Monday 21st March 2022, and both the audience and the press were immediately seduced.

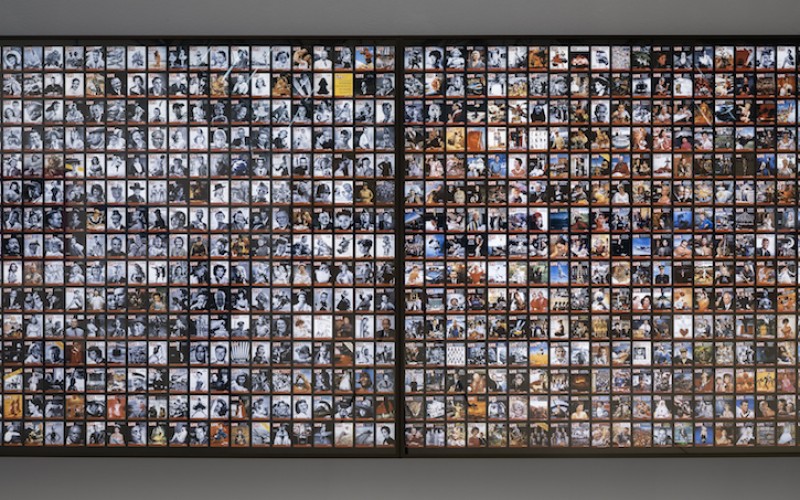

The Procession is a unique piece in its kind. Inspired by the tradition of Caribbean carnivals, as much as historical marches and protests, the 150 hand-made, life-sized figures comprise men, women, children and horses, in long lines that defy the imagination, holding or carrying banners, flags, musical instruments, maps, boxes and many more objects.

Hew Locke's 'The Procession' at Tate Britain

'For this commission, I immediately thought of many possibilities,' Hew adds, 'and soon came the idea of the procession. I knew it would be hard work, so I talked a lot with my partner, the curator Indra Khanna, and with artist assistants. My goal was to achieve something I had never done before, so I knew I'd need a team to make it work. First, I wanted to make all these characters, but I also wanted to create my own fabrics, with images of my own work.'

For the senior curator, Elena Crippa, 'knowing his previous work with the themes of empires, statues, journeying, migration, we thought a blank canvas would be a great fit. With his patchwork of textile, embroideries and cardboard, he managed to create a new series of references, connecting these places, people and events culturally, historically but also aesthetically, with a special selection of colours, all in a joyous encounter.'

Hew Locke's 'The Procession' at Tate Britain

Altogether, this process took about ten months of work, conducted mostly during lockdown, from January 2021. 'We had to work on Zoom and sent each other photos of the space and of the pieces we made via WhatsApp,' Hew says. 'This way, I managed to first come up with one file of figures, then a second, knowing that I wanted to generate a whole crowd... All came from my imagination, and my main inspirations were from my own experiences, in Guyana, in processions. For me, these were most of all joyful. They can also be intense or scary, or open-ended events. But it was important to me to respond to dark times with joy, even to transform the dark into joy.'

Hew Locke's 'The Procession' at Tate Britain

The large variety of elements included in the installation, made originally of cardboard and fabrics, allowed the artists to bring in a vast array of references to historical and political events, from the colonisation of the Americas to the Haitian Revolution, as much as the abolition of slavery and its restoration by Napoleon, but also of geographic points, including Guyana of course, West Africa and especially Nigeria, Europe, China and Russia.

'I have an obsession for details,' the artist confesses, 'so I needed to mitigate this with the urge to work fast, almost like a factory, in order to make such a production possible. I started with the big colourful flags, to raise the eyes of the public, the banners, like in any real parade. My point is that I cannot live in misery, so, even if I do want to deal with difficult, political issues, I need to make them liveable. I focus on uplifting. I also wanted to include the participants, not to dictate how they should react or read the installation.'

Hew Locke's 'The Procession' at Tate Britain

Walking through the hall, the audience does feel like joining The Procession, and through its experience, the numerous references start making sense at different key points.

'For instance', Hew Locke says, 'the Chinese certificates are from the Imperial Government of China, from a time when it was dominated by the West. Today, the situation has changed... It is there to show that forgetting the past is a mistake.' Same with the document referring to the Russian General Oil Corporation.

Hew Locke's 'The Procession' at Tate Britain

In the article 'Transformations of Western Icons in Black British Art', Professor Ingrid von Rosenberg wrote that 'artists who continue to produce work with a critical message, like Yinka Shonibare and Hew Locke, avoid the open confrontation typical of the 1980s. Instead, they use humour and satire, positioning themselves as cultural insiders, rather than excluded outsiders.'

I ask him how he felt about the political appeal of his work and if he still believes it is better to avoid taking sides. 'With some elements, it's true, I don't want to take sides, but with some others, I have to. My goal is to show the complexity of things. This piece is a summary of a lot of pieces I've done; it voluntarily includes my catalogue. It's trying to reach a certain universality; it's not tied to one country.'

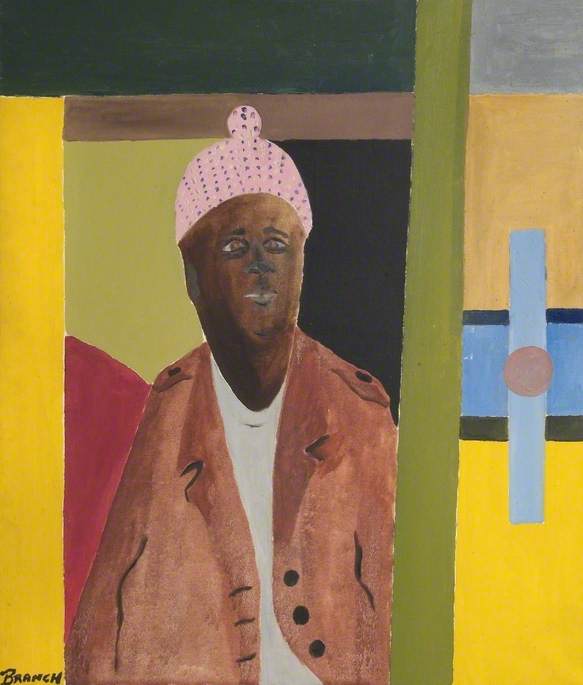

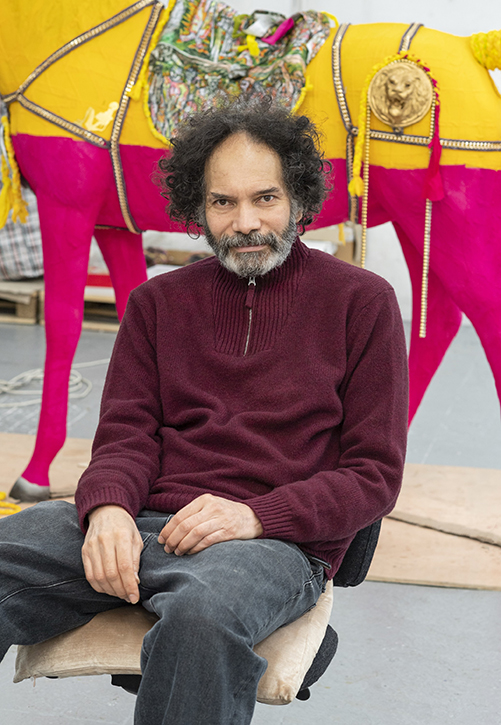

Hew Locke

Born in Edinburgh in 1959, Hew Locke grew up in Guyana (formerly British Guiana) from 1966 to 1980, before moving to England as a student. He received a BA in Fine Art in 1988 from Falmouth University, and an MA in Sculpture from the Royal College of Art in 1994. His links to the Caribbean, as well as South American and British culture, inform his art deeply.

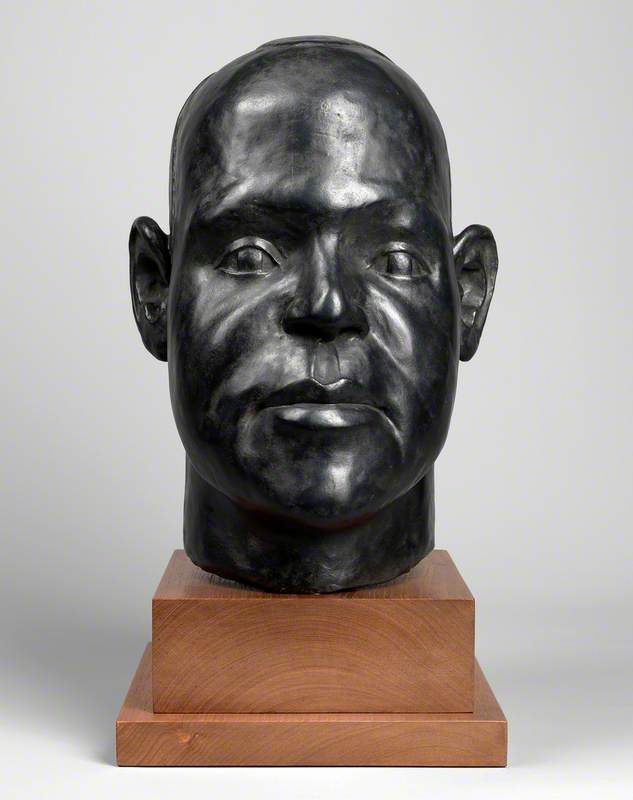

A lot of his work dealt with the legacy of the British Empire. Restoration was based on the embellishment of the statue of slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol – now famous for its toppling during a Black Lives Matter protest on 7th June 2020. The piece was commissioned in 2006 by the Spike Island gallery. Locke had, at the time, adorned it with cowrie shells, jewels and trade beads. He used a similar process in his piece Columbus, in New York's Central Park, in 2018.

Columbus

2018, chromogenic print with mixed media by Hew Locke (b.1959). Central Park, New York

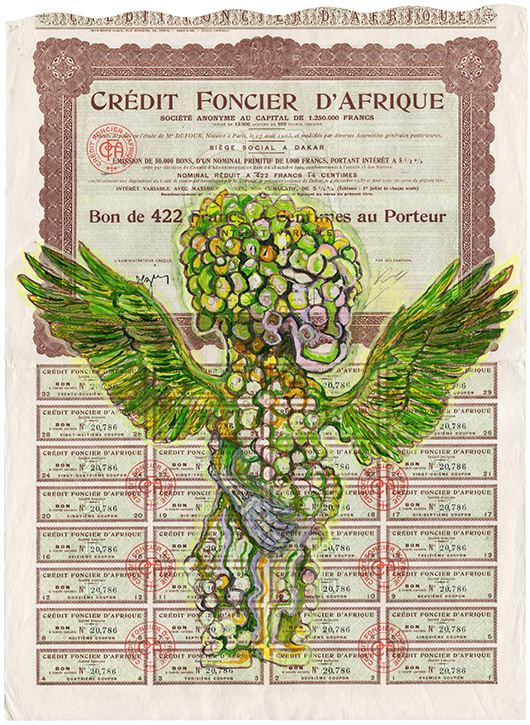

In works like Crédit Foncier d'Afrique, from 2014, Locke already used historical trade archives and drawings to decry the unfairness of western rules of trade.

Crédit Foncier d'Afrique 1

2014, mixed media by Hew Locke (b.1959)

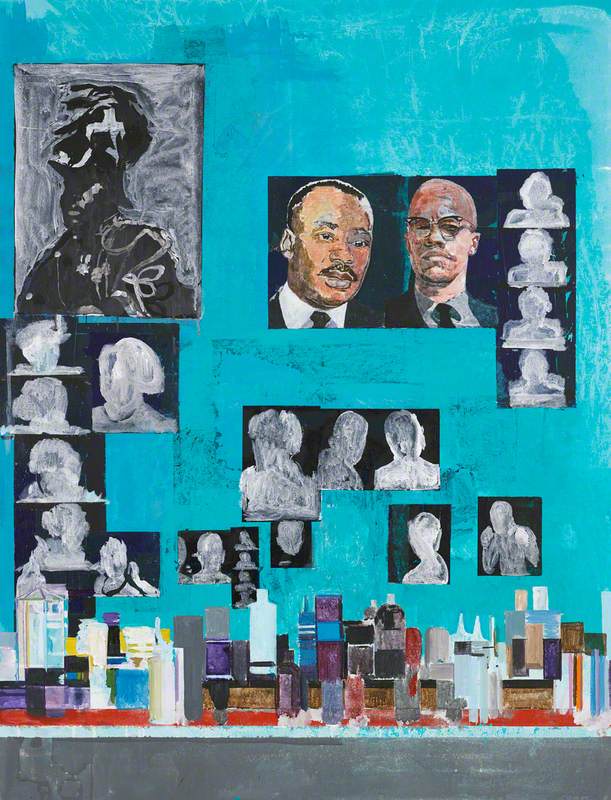

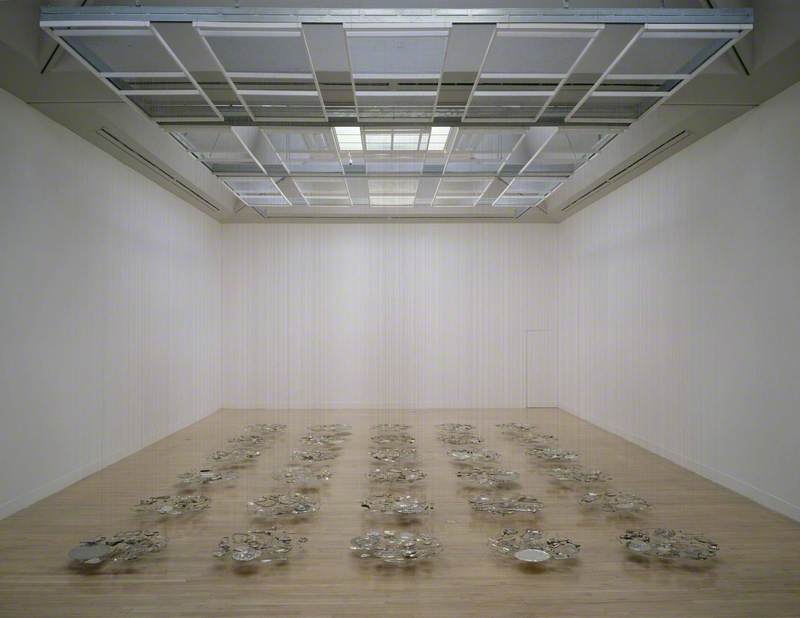

With his more recent work, Here's the Thing at Ikon Gallery in Birmingham in 2019 – his most comprehensive exhibition to date, involving painting, drawing, photography, sculpture and installation – he explored 'the languages of colonial and post-colonial power, and the symbols through which different cultures assume and assert identity'.

Installation view of Hew Locke's 'Here’s the Thing' at Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, 2019

Hew Locke's universality rings particularly true when it comes to displaying the logic of empires. 'It shows how they collapse. I run threads of all empires, the British, the French, the Ottoman... And I care to show what happens at the end of that. As a procession, it can show that even if light sometimes contains darkness, darkness has light in it too, always.'

Melissa Chemam, writer, cultural journalist and reporter

'The Procession' is at Tate Britain until 22nd January 2023

*Professor Ingrid von Rosenberg, 'Transformations of Western Icons in Black British Art', Journal for the Study of British Culture, vol. 15/1, 2008