We are living in surreal times. This is a thought that often arises in me, in response to a myriad of experiences I've had: from overwhelming beauty to levels of horror I cannot compute. Mostly these experiences have been mediated through the black enchanted mirror of my phone screen, which is within arm's reach of my body – if not in some way connected to it – at all times.

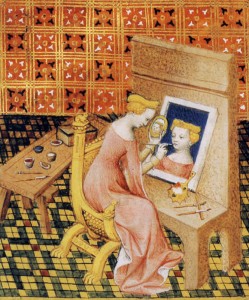

My phone has expanded both my own reality and my ideas of realness itself, in ways that are irreversible. I have found a mirror of this in art: both in surreal art and in the long tradition of painting window views – two particular interests of mine.

Here, I have chosen six paintings from Welsh collections to explore how modern technology expands our understanding of 'windows', and how we relate to our environments through them.

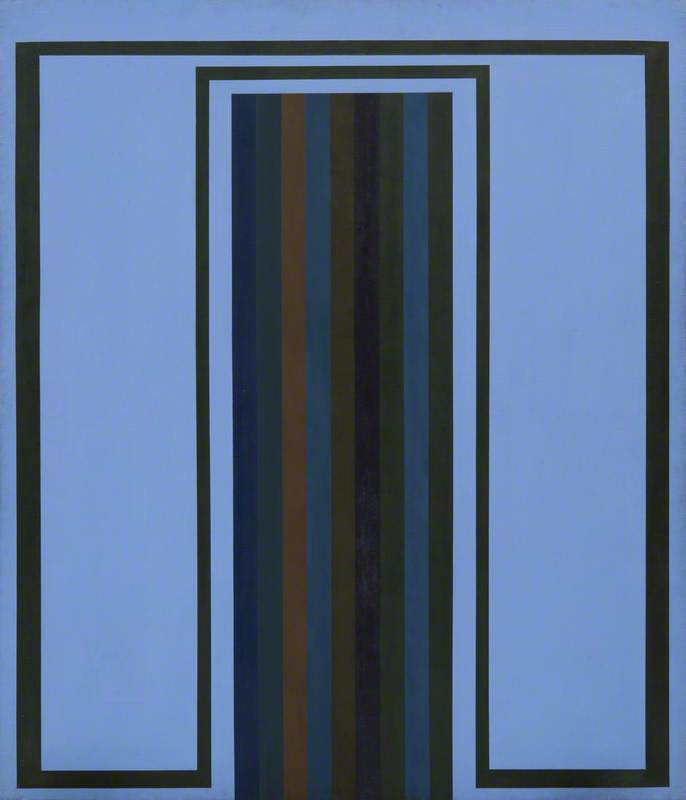

Ken Elias' Windows in Newport Museum and Art Gallery provides a compelling starting point. The work encapsulates the idea of modern technology being a counterpart to windows – as a means through which we view and experience the world – by projecting, in a dreamlike fashion, the view from the television, directly next to the 'real' window in the room.

The physical proximity of these two 'windows' in the painting speaks to how both reveal the 'liveness' of the world in motion. We could extend this likeness to also include other technological 'windows', from computer screens to smartphones and VR headsets – each expands our perceptions far beyond the physical confines of our immediate surroundings.

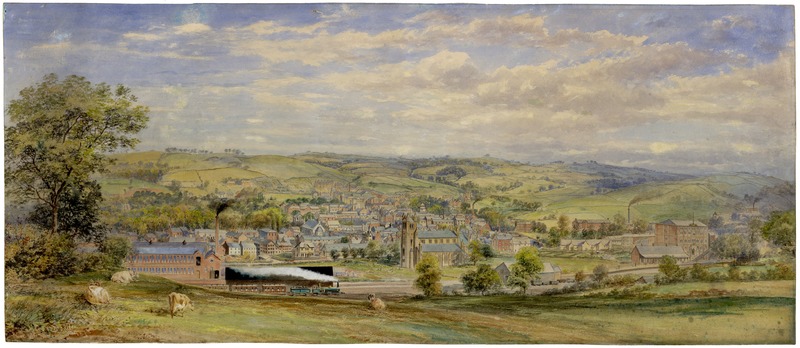

Windows, the regular kind, are also not just confined to stationary buildings. Trains are my favourite form of transport, because of the large windows they have in comparison to other vehicles. This, married with the speed at which they reveal their views, is alluring to me. Windows on transport vehicles were among the first instances of experiencing a changing world from a stationary position, and as such have primed us for our consumptive relationship with the windows of our phone, computer and television screens.

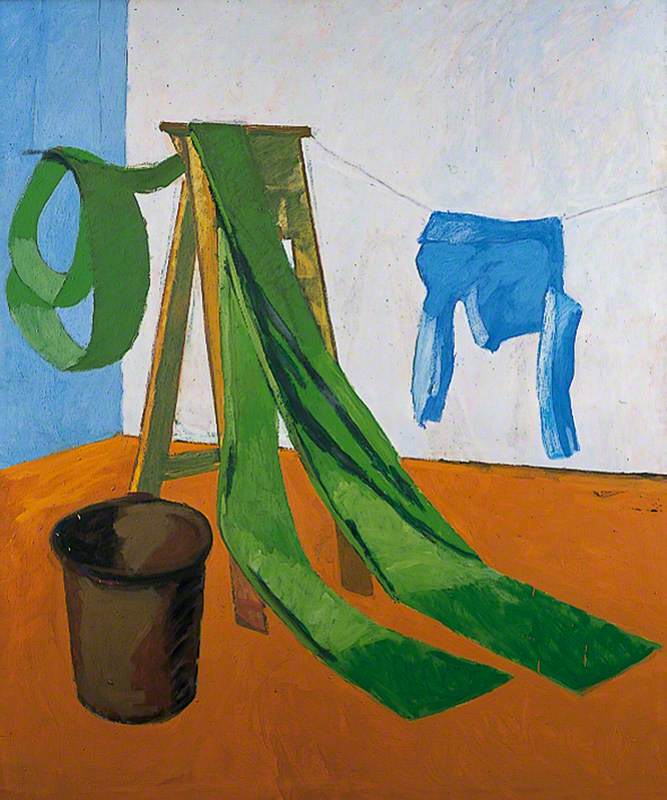

View from a Railway Carriage; Snowdonia from the Cob

Anna Todd (b.1964)

Anna Todd's View from a Railway Carriage; Snowdonia from the Cob, at University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, offers an intriguing lens through which to examine the history of viewing changing landscapes from a stationary position. This painting is interesting in choosing to represent the landscape as still, though, in reality, views from train carriages are rarely still.

Todd's choice to depict a stationary landscape from a moving train underscores the tension between movement and stillness. This mirrors our modern experience with digital screens, which also act as advanced windows to distant parts of the world. However, unlike the passive observation from a train window, digital screens afford us a degree of control over what we view, thus altering the nature of our engagement with the world.

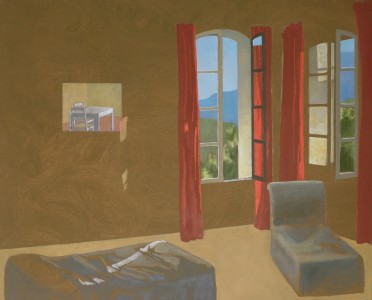

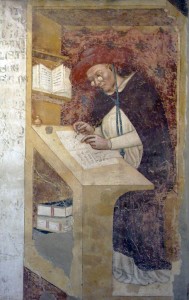

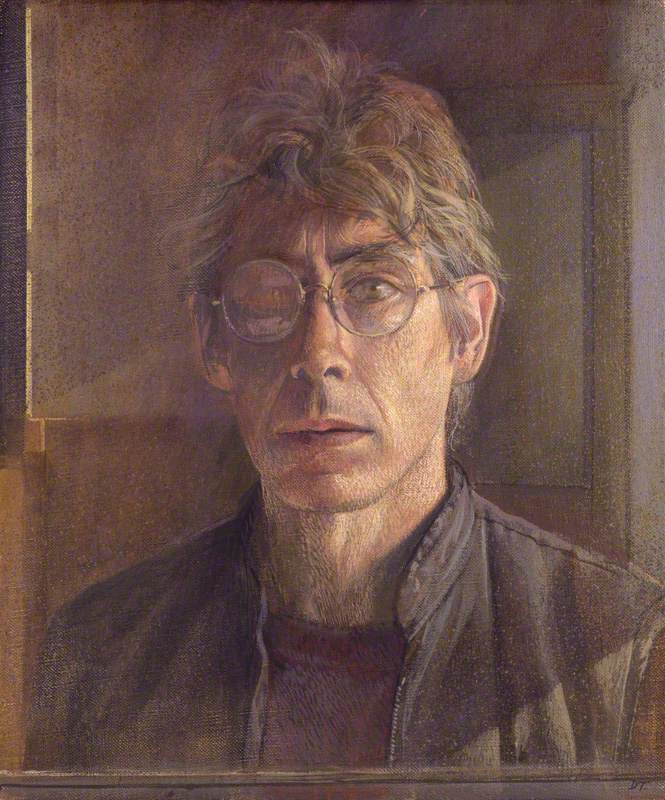

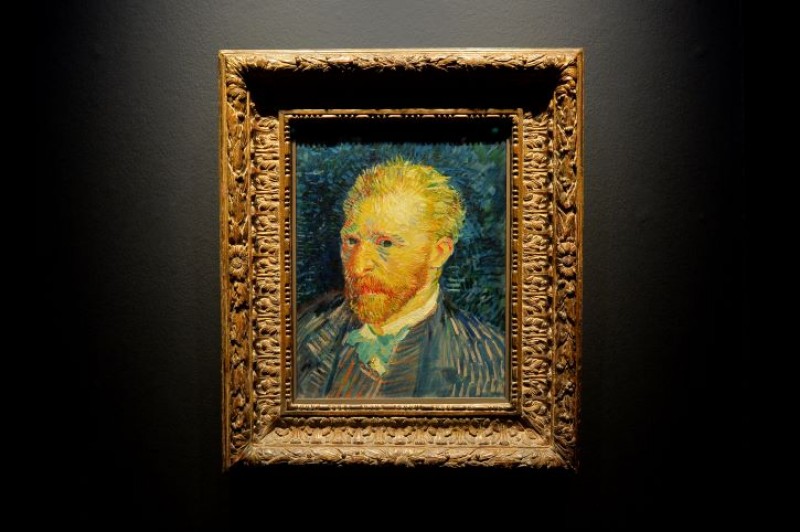

Tony Steele-Morgan's surrealist paintings South Wales and Tiger Mirror Box speak to this further by depicting windows that reveal realities distinct from what we expect to see from them. South Wales portrays an idyllic, natural environment, echoing our desire for picturesque visions of nature within our local context, but for many of us who call south Wales home, this image of a manicured nature is not what lies just outside our homes.

This work also raises questions about our yearning for idealised natural settings as part of our local environment. This yearning has been amplified in recent times, driven by our interaction with technology, which feeds us an almost constant array of idealised, montaged, edited and filtered versions of lives that are perhaps possible to live, but not with the ease that is depicted.

Conversely, Tiger Mirror Box introduces exotic and distant elements into an urban experience through the metaphorical 'mirror box'. This work challenges our perception of what is local by bringing far-flung aspects of the world into our immediate experience, blurring the lines between local and global. The contrast between these two paintings illustrates the dual role of technology: it can reinforce our appreciation for local nature while simultaneously integrating distant, diverse elements into our everyday lives, in a way that previous generations simply did not have access to.

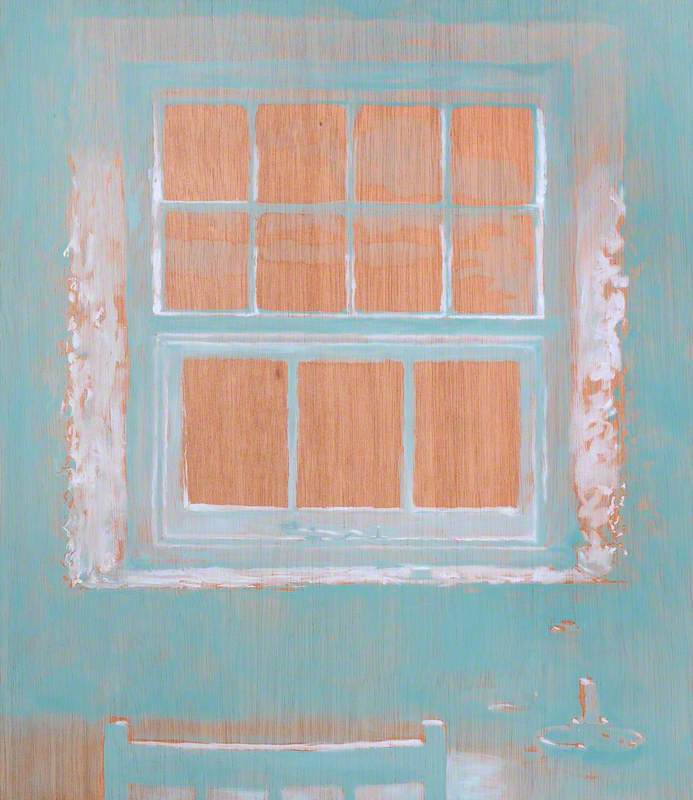

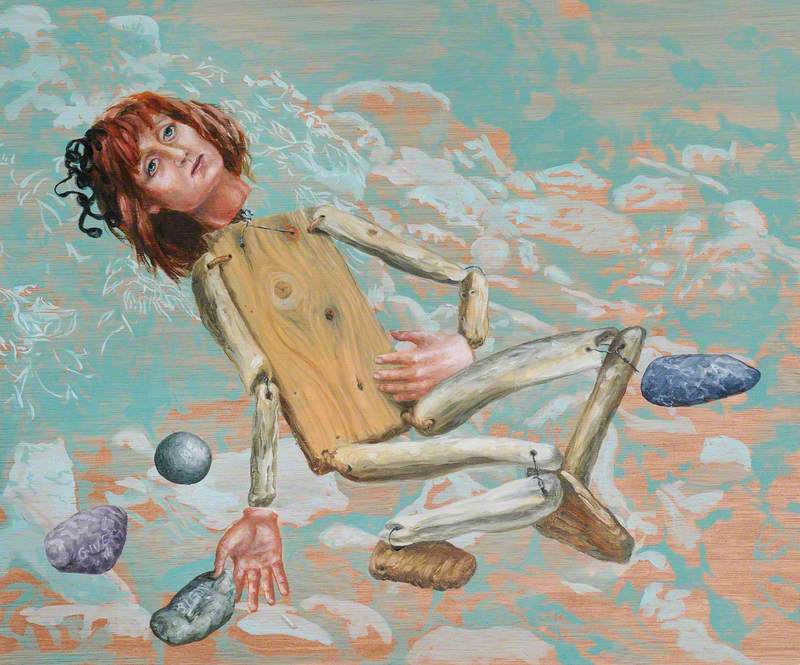

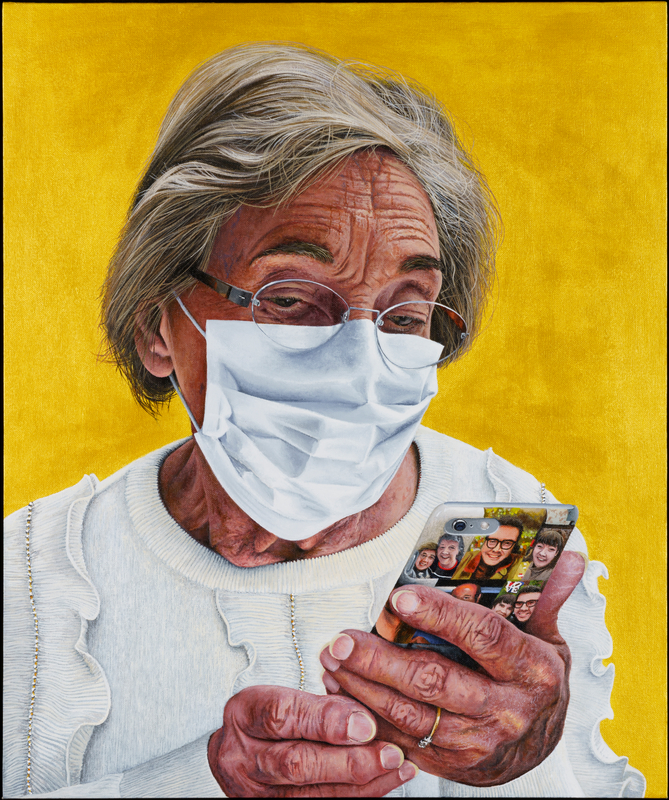

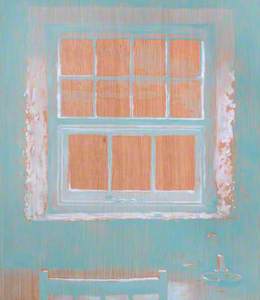

Susan Adams' painting from the series Waiting for Something, 1–30 also draws a parallel between traditional windows and modern screens in terms of their framing function. Windows and screens alike frame action, and in doing so are simultaneously revealing and obscuring. This duality often goes unnoticed as we passively consume content through screens, much like we might sit by a window and watch the world go by.

Adams' work invites us to reflect on how this passive, detached mode of viewing has been ingrained in us through our interaction with windows and how it translates into our digital habits.

Of course, we are not always passive consumers in our relationships to windows and screens – our active participation via screens is easily brought to mind – and so the question remains: how might windows reveal us to the world, and not just the other way around?

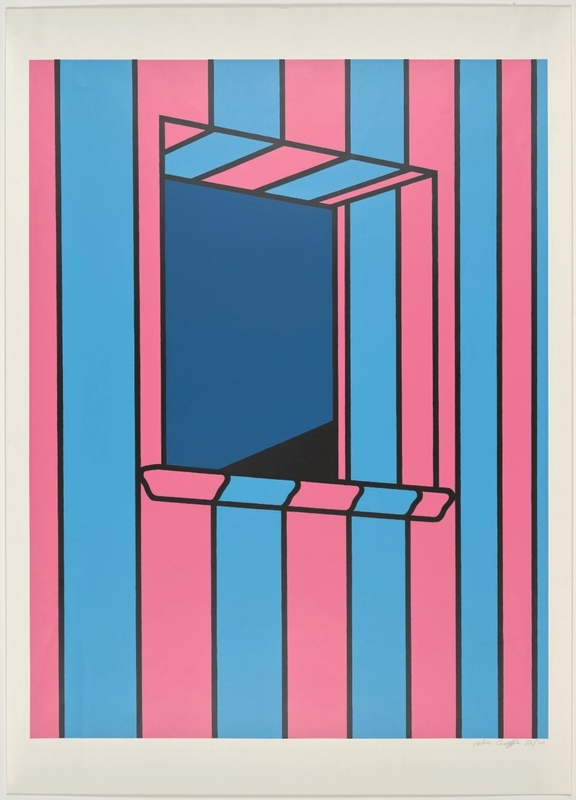

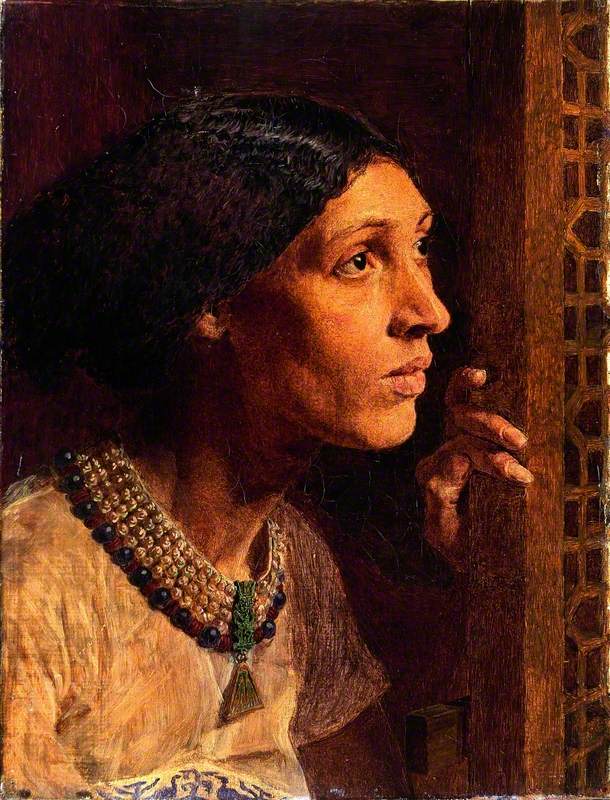

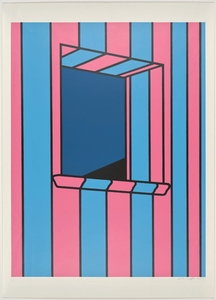

Patrick Caulfield's Small Window at Night, at National Museum Cardiff, shifts the focus to how windows frame us as observers, especially in domestic settings. At night, when curtains remain undrawn, windows turn us into actors on a stage, watched by passersby. This artwork underscores the importance of recognising our role, whether passive or active, in relation to the various windows in our lives.

By consciously reflecting on and opting in and out of these interactions, I'd like to believe we can better understand how windows influence our perception of the world, and begin to question what we might want to do with this influence: factoring it into our decisions about how we want to live, rather than letting its influence float in a room – much like a window might do.

Umulkhayr Mohamed, artist, writer, curator and educator

This content was supported by Welsh Government funding

Further reading

John Berger, About Looking, Pantheon Books, 1980

Anthony Longo, Being and the screen: How the digital changes perception, 2019

Dr Divya P. Tolia-Kelly and Professor Gillian Rose (eds), Visuality/Materiality: Images, Objects and Practices, Ashgate, 2012

Bronislaw Szerszynski and John Urry, 'Visuality, mobility and the cosmopolitan: inhabiting the world from afar', British Journal of Sociology, 2006