A notable feature of the work of Francisco Goya (1746–1828) are sequences of images that can be read as a narrative whole. His famous series Caprichos (Caprices) and Desastres de la guerra (Disasters of War) find their equivalent in his early career in tapestry cartoons designed to tell an episodic story in the rooms for which they were made.

Francisco Goya (1746–1828)

mid–19th C–late 19th C

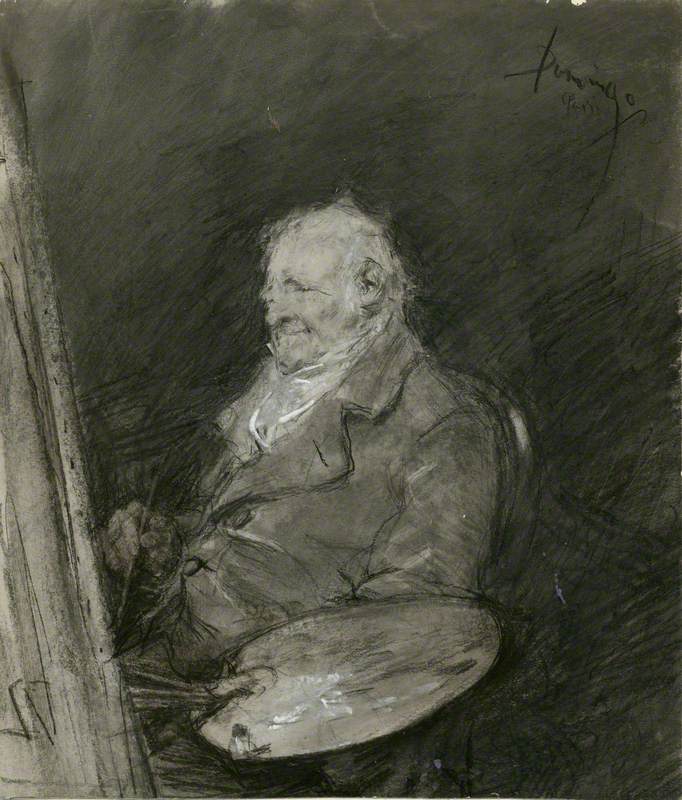

Francisco Domingo Marqués (1842–1920) and Francisco Domingo Marqués (1842–1920)

The varied works by Goya in UK collections may not appear to tell a coherent story, but there is a discernible common theme. The early, playful bucolic works are followed by a period of extraordinary portrait painting, including the famous Wellington portrait in The National Gallery. Then in the last 20 years of his life, Goya produced his disturbing imagery of war and phantasmagoria.

What then links these very different works? Goya's subject is power and its abuse: power over others and the individual's sense of their own power.

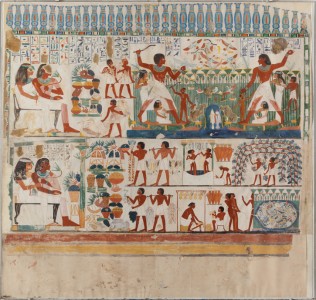

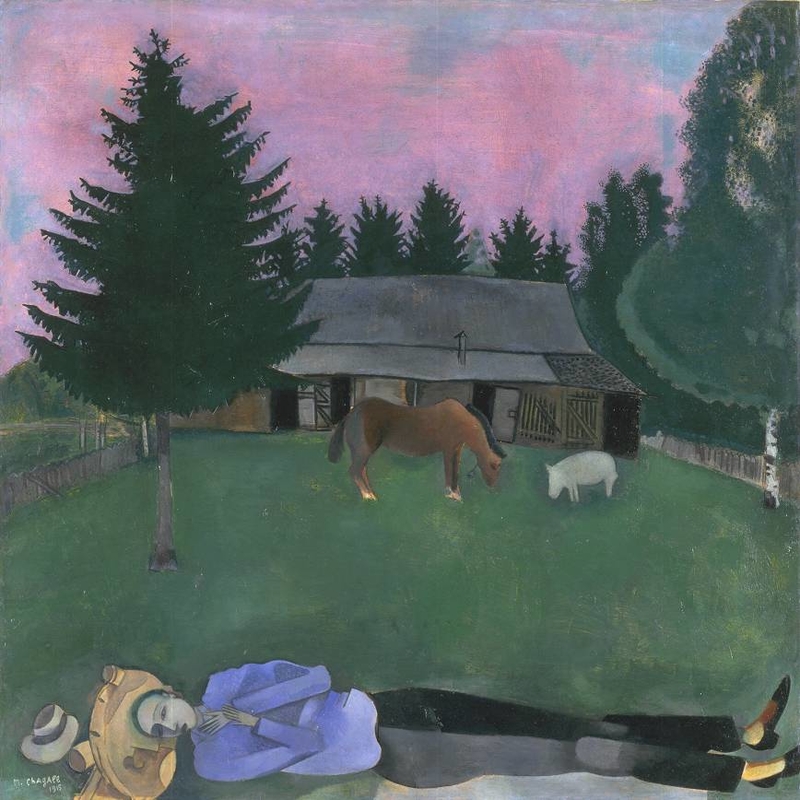

This theme finds its expression in early paintings, many of which were cartoons for tapestries made for the Spanish royal palaces of El Pardo and El Escorial between 1775 and 1792. Charles IV had asked that these images be 'rural and humorous', and among the cheerful genre and hunting scenes we find children play acting as adults and adults at leisure.

A Picnic would seem to be a benign scenario. But Goya uses it to display opportunism in the figure of the man in the centre, who appears to be moving in on the girlfriend of his drunk and vomiting colleague. She is faced with what might be a dilemma – she seems unimpressed with both men, yet undecided. The libidinous urge wants to take advantage of weakness – both actual and presumed.

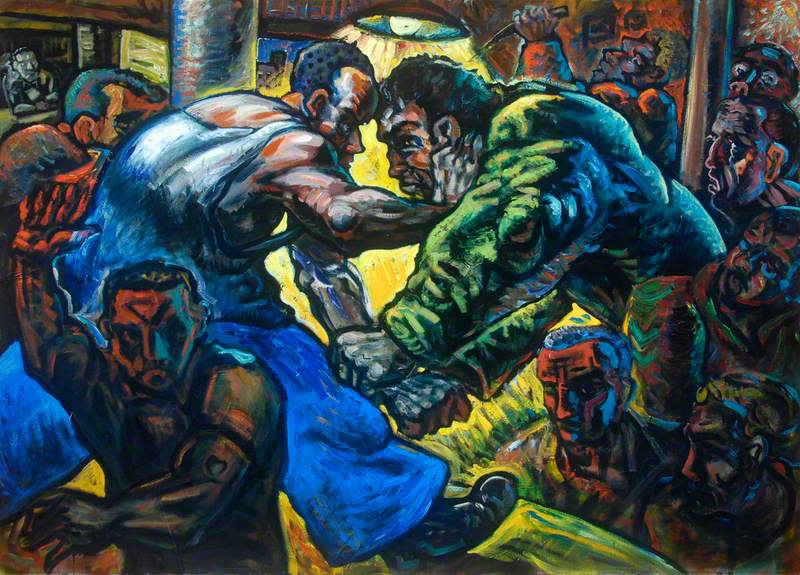

In a separate series painted around 1780, Goya portrayed children's games, and in Boys Playing at See-Saw, the games are familiar tests of physicality. Goya has dressed his children in adult clothes: two in priest's cassocks observe and the boy in the air is dressed as a friar. There are those who struggle and risk injury – the wrestling soldiers – and those who look on and judge. Literally outweighed by the grounded couple, the friar enjoys his elevated position too much, perhaps. A watching dog is tethered, powerless.

In Boys Playing at Soldiers, one boy appears to plead for his life (or pay grovelling homage), while another bows to the smiling victors. The paper headgear and sashes remind us that this is juvenile pretence.

The Doctor is a cartoon which Goya designed for an overdoor tapestry, at which height the doctor's bold red cape would blaze forth – it does in fact appear to be a fiery emanation of the glowing coals. The doctor is presented as a figure of stature, warming his hands in a wintry landscape with his assistants standing by. The open books indicate his learning, and his clothes and cane reveal a man of means.

By 1792 Goya had grown dissatisfied with working on tapestry cartoons, and this coincided with the illness that would leave him completely deaf. This illness remains a mystery, but a theory favoured by scholars is that he was poisoned by the toxins (notably lead) in his paints, aggravated by his habit of sucking his brushes and painting with his fingers.

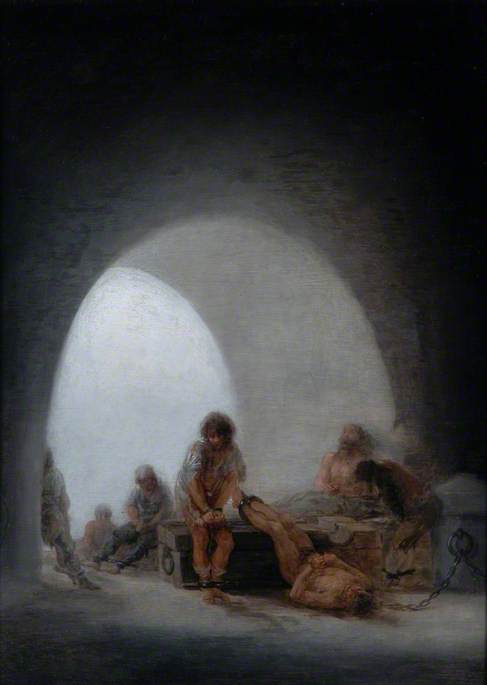

An important strand of Goya's work is his interest in the plight of the incarcerated – the criminal and those considered mad. Robert Hughes accounts for this preoccupation as a response to his sudden deafness, which he likens to imprisonment in its traumatic effect of isolating the individual from society. A profound sense of impotence pervades Goya's Interior of a Prison. Each prisoner, hands and feet chained and in utter despair, meditates on his dreadful situation. The arch, like a great sensory opening, lets in nothing but an opaque grey fug.

In a letter of 1794, Goya explained that he had found these bleak themes whilst in the grip of his own suffering, making 'observations of subjects which in general are offered no place in commissioned work and in which there is no room for fantasy and invention'.

In later scenes of a madhouse, however, the inmates are animated, emboldened by their afflictions. Although the cold light still mocks them, within their cell, power is fancifully assumed and asserted. One man wears a paper crown while another points an imaginary pistol. Yet another sings, holding a pretend flute – the creative impulse will not be entirely snuffed out.

La casa de locos

c.1814–1816, oil on canvas by Francisco de Goya (1746–1828)

Goya began portrait painting in his late 30s. His subjects range from friends to the Spanish royal family, and each figure is presented faithfully, their psychology to the fore.

Goya's friend Juan Antonio Meléndez Valdés was a poet and a judge who sought to improve the conditions in prisons and hospitals. He was one of a group of liberal-minded figures who gave optimism – if only briefly – to the aspirations of those, like Goya, who hoped for a reformed and enlightened Spain. This portrait was made at that time, although Valdés appears pale and careworn. He seems far from confident, harried even, reflecting perhaps an inner anxiety that their mission would founder.

Goya's portrait of Francisco de Saavedra shows a man in a hurry. Saavedra had just been made Minister of Finance. Rather than weighed down by his responsibilities, Saavedra is alert and ready for action – a reflection perhaps of his military background – and it seems he posed only long enough for Goya to paint his head, while the rest of the picture is painted in looser brushstrokes.

Don Francisco de Saavedra

1798

Francisco de Goya (1746–1828)

Saavedra was dismissed from his position within months and his fall from power (along with another reforming colleague) has been discerned in an etching titled Subir y bajar ('To Rise and to Fall'), in which two figures, their faces unseen, tumble to earth.

Unlike Saavedra, who Goya shows looking out of the picture space, as though seeking his next challenge, the portrait of the court gilder Andrés del Peral engages us directly. Peral seems guarded and even disdainful, but this impression is partly due to his lopsided mouth, likely the result of a stroke.

As the senior painter of the Spanish court, Goya followed his great forebear Diego Velásquez in presenting members of the royal family as they were – a distinctly unattractive group. As John F. Moffitt puts it, Goya's portraits 'show a new emphasis upon psychology over physiology, and psychic immediacy over the signs of rank'.

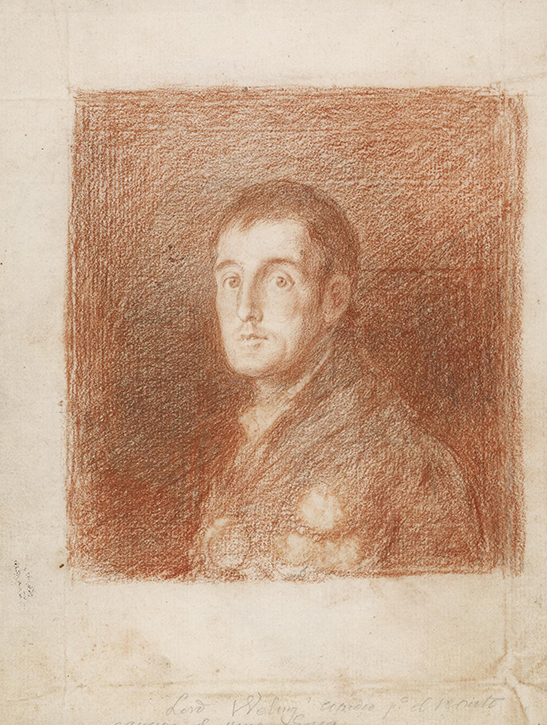

Military rank, too, is no protection from Goya's perceptive eye. His portrait of the Duke of Wellington is a remarkable study of human vulnerability, especially as it was painted after a victorious Wellington had entered Madrid in 1812. Wellington's forces had just defeated Napolean's armies, allowing the liberation of the Spanish capital, when Wellington sat for his portrait.

Although Wellington's tunic is studded with medals and insignia, there is nothing heroic in his appearance. He looks at us with sad surprised eyes, exhausted from battle. It is a young, almost boyish face, forlorn and lost. In Goya's hands, even the supreme military leader – the so-called 'Iron Duke' – soon after victory, is presented as defeated.

Wellington appears even more cheerless and frail in a drawing made in red chalk, which was thought to be a preparatory study for the oil painting.

Goya also produced an equestrian portrait of Wellington. There was poetic symbolism in the making of this image: Goya painted Wellington over another mounted figure in an existing portrait, probably Joseph Bonaparte, who had been installed as king of Spain in 1808 by his brother, Napoleon. Thus, as the French were forced out of Madrid, Bonaparte was usurped in paint by the victor Wellington.

Equestrian Portrait of the 1st Duke of Wellington (1769–1852)

1812

Francisco de Goya (1746–1828)

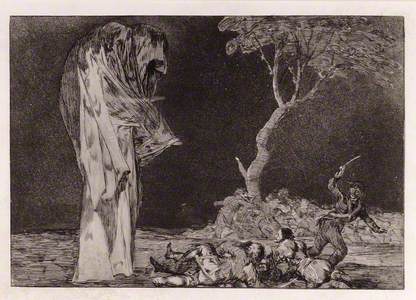

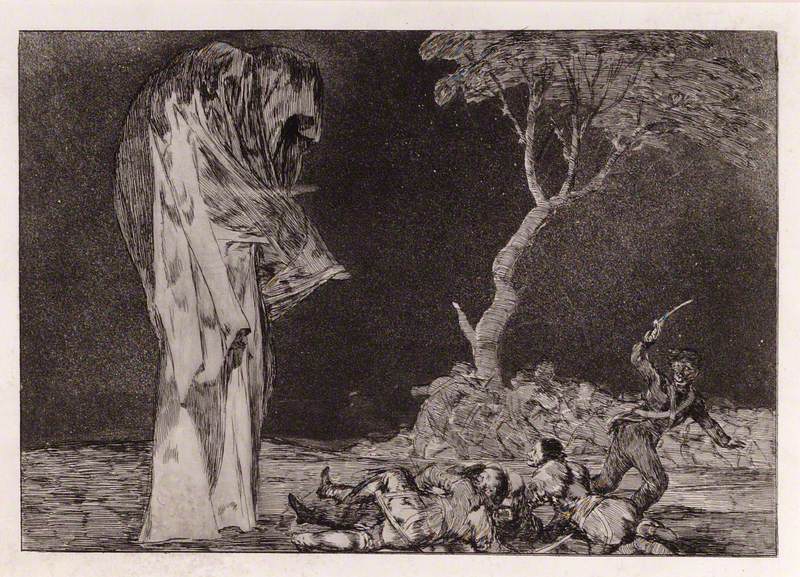

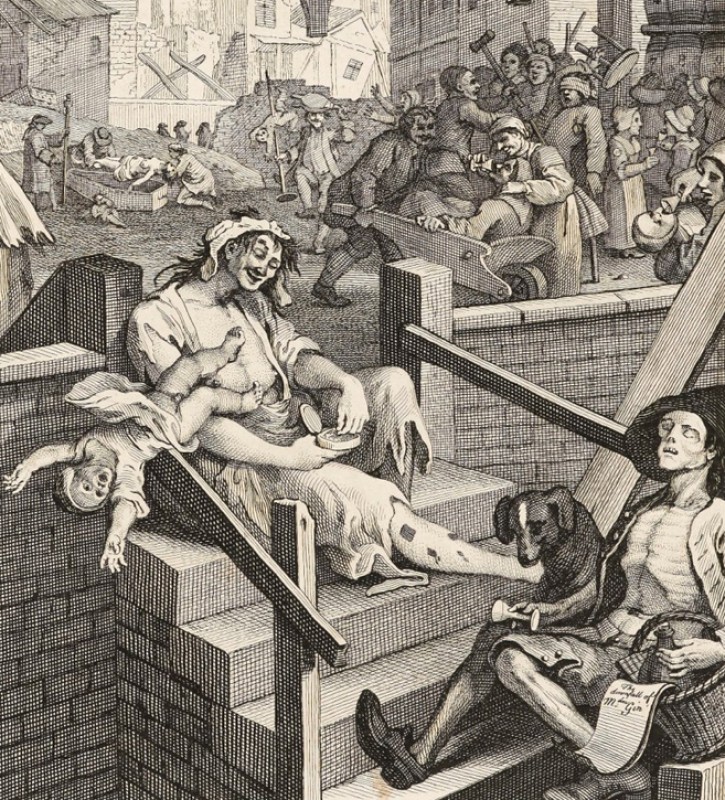

'In etchings that defy reduction to logical explanation, invention triumphed.' This is one assessment (in Janis A. Tomlinson's Goya) of the 'Disparates', a series of etchings that Goya produced in the last ten years of his life. 'Disparate' translates as 'folly' or 'irrationality', so Disparate de Miedo is 'Folly (or Irrationality) of Fear'.

A towering ghost – Death itself – looms over a group of prostrate soldiers, while one runs away. Look closely: some scholars say a face (or a mask) can be discerned peeping from the phantom's right sleeve. At a time of incessant warfare, terror was normalised and military bluster quickly dissipated. The power of the fighting man was compromised by fear and the reality of war.

The subversion of power is the theme of several of the 'Disparates', whether that be denigration of the military (as in Disparate de Miedo), the clergy or traditional ideas of male dominance. Disparate de Miedo provides a link to another of Goya's sequences, the horrifying 'Disasters of War' series – with its battlefield scenes of unspeakable cruelty – as well as to those many images of witches and grotesquerie which became a rich vein of his later work.

A Scene from 'El Hechizado por Fuerza' ('The Forcibly Bewitched')

1798

Francisco de Goya (1746–1828)

Although Goya denied any personal fear of creatures of the night (as he claimed in a letter written around Halloween 1787), he had an obvious preoccupation with witches and ghouls. Some scholars have suggested that this is partly explained by Goya's awareness of popular fascination and public entertainments of the time. This is true of A Scene from 'The Forcibly Bewitched', which depicts the moment in a drama when a priest, believing he has been cursed and will live only as long as a lamp remains lit, refills the lamp with oil. A further theory is that belief in witchcraft is a sign of mental disorder, namely melancholy.

Robert Hughes suggests that witchcraft was a potent idea even among the enlightened, who saw witches as Devilish agents. Infant mortality was alarmingly high by modern standards, and Goya and his wife had lost several children in infancy. Witches represented as child snatchers appear in The Witches' Sabbath and The Spell (both 1797–1798).

Especially in later life, Goya felt a licence to create fearlessly and with unrestrained imagination. It seems that nothing was too shocking or mysterious.

A relatively mild flight of fancy is Cantar y Bailar ('Singing and Dancing'), a watercolour from a private album, in which a singing guitarist appears to float over the head of a seated observer.

Cantar y Bailar (Singing and Dancing)

1819–1820

Francisco de Goya (1746–1828)

The observer is wearing a smiling mask and holding its nose – a critique of the music, perhaps, or a response to what is visible beneath the singer's skirts? Even in a slight work such as this, there is a twist – although the true expression of the sitter is masked by a smile, they cannot help but gesture their disapproval. Thus the feat of levitation – a supernatural elevation above the earthbound – only draws ridicule.

In the portrait of Doña Isabel de Porcel, we are faced with a confident beauty, beautifully made. What more is there to say?

It may come as no surprise that scholars now doubt that Doña Isabel is by Goya's hand, both for the quality of its execution and the lack of a sense of the sitter's psychology. As Robert Hughes writes, more than anything else, Goya abhorred hypocrisy. The truth and its expression mattered most to him. So if Doña Isabel is by Goya, she is presented in all her beauty, without qualification, because that is what she was. For a troubled artist in troubled times, Doña Isabel may be a rarity.

Goya lived to a grand old age. Prolific and versatile, with an extraordinary range, he is the last of the old and the first of the new masters of his art, like his contemporary and fellow sufferer of deafness, Beethoven. He was startlingly modern, innovating in the realms of the unreal and the irrational, as well as the all-too-real miseries of humankind. The theme of power is both timeless and very much of his time, when warfare, political jockeying and pitiless cruelty were insistent features of the life he knew.

Adam Wattam, writer

Further reading

Robert Hughes, Goya, The Harvill Press, 2003

John F. Moffitt, The Arts in Spain, Thames & Hudson, 1999

Janis A. Tomlinson, Goya: A Portrait of the Artist, Princeton University Press, 2020

Sarah Symmons, Goya, Phaidon, 1998

Sarah Symmons (ed.), Goya: A Life in Letters, Pimlico, 2004

.jpg)