Looking back at it, hundreds of years later, seventeenth-century Dutch society could be captured through stories of flowers and painting.

Centuries later and we are still gripped by the fable of tulip mania, the three years from 1634 to 1637 of economic and horticultural hysteria that saw fortunes created and ruined on the promise of beauty, when single tulip bulbs would sell for ten times the average wage. It's become a talisman for an economic boom-and-bust cycle, but for me – a gardener and sentimentalist – tulip mania speaks of how far people will go in order to control nature.

By the time Dutch master Rachel Ruysch was born, in 1664, tulip mania was three decades in the past but the Dutch Golden Age was firmly established. This small country straddled between land and sea was experiencing a revolution in art. Unshackled from Spanish Catholic rule, the newly independent Dutch Republic asserted itself on canvas.

As new trade connections boosted income, so the middle and merchant class expanded. Artists began to depict ordinary lives: women in headscarves with pails of milk and pearl earrings, dusky goldfinches delicately chained to a perfectly sized feeder, surgeons and self-portraits and sky-lightened floors. These were the pictures people wanted to spend their new money on.

Still Life with Beaker, Cheese, Butter and Biscuits

Floris Gerritsz. van Schooten (c.1585–after 1655)

Among the human lives on canvas, the still ones. It was here, on these tablescapes of swagged cloth and burnished brass that the Dutch Golden Age could whisper its success. Butter mountains and crystalline cherries and, both in the scene and out of it, the cost of enslaved human life that filled the coffers of the white European trader, stolen and transported on Dutch East India Company ships as if it were spices or coffee.

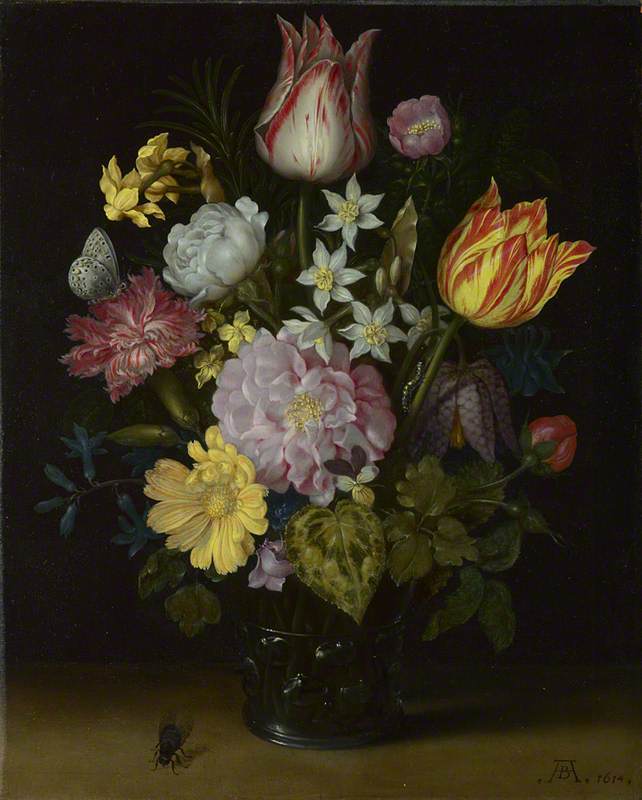

And among all this, there were flowers. Before the big tulip mania crash, Ambrosius Bosschaert the elder made them something of a staple in his flower studies, to the extent you can imagine him filling his vases with flowers bought on different days.

He painted the fresh ones, their petals lush and immaculate, the stripes well-defined, and he stood them next to those reaching the end of their tether: the base of the petals holding onto the flower stem with featherlight desperation in A Still Life of Flowers in a Wan-Li Vase on a Ledge with further Flowers, Shells and a Butterfly (1609–1610), or flaring like a ruffled skirt in Flowers in a Glass Vase (1614).

Christoffel van den Berghe followed in Bosschaert's floral footsteps, folding billowing striped tulips in vases with narcissus and butterflies.

Still Life with Tulips and Carnations in a Glass Vase

Christoffel van den Berghe (c.1590–1642)

Tulip mania came and went, but just while the price of tulip bulbs may have diminished, their popularity in the Netherlands remained intact. Flowers were in fashion, and therefore paintings of flowers were in fashion. Among the reams of male painters taking on still lives alongside landscapes and portraits, a few chosen women were able to rise to the top, including Clara Peeters and Ruysch.

And this is where we return to Rachel Ruysch: artist, businesswoman, mother to ten children, painting pioneer. Hers is a life that would make an excellent film, really. Perhaps one day it will. She was a child of undeniable privilege: her grandfather was a master builder for the House of Orange, and she was surrounded by painter uncles. Ruysch's father was an influential anatomist, Frederik Ruysch, who imbued her with a keen and curious eye for botanical detail. She, in turn, taught him to draw.

The family were known in Amsterdam for her father's macabre collection of specimens – examples of his revolutionary method of embalming, displayed for beauty as much as scientific discovery. The arrangements would be considered the stuff of nightmares today: jars of organs mingle with flora and fauna. A baby's hand holding a hatching turtle egg.

But it became a family affair: by her late teens, Ruysch collaborated with her father on the exhibits, arranging dioramas and sewing items for the bizarre displays. Among the foetal skeletons, bladder stones and blood vessels were tiny flower crowns and bouquets – a flourish from an adolescent Ruysch's botanical brain.

When she was fifteen she was apprenticed to Willem van Aelst, a friend of her parents who happened to be considered the greatest still life artist in Amsterdam.

Under him she built on the keen aptitude she'd shown for painting plants and animals, and from him she learned discipline: the smallest brushes to depict blades of grass, a pinch of moss to capture the texture of a bryophyte, a butterfly's wing to render the ephemeral permanent.

Still Life with Fruit, a Bird's Nest and Insects

1710 or 1716

Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750)

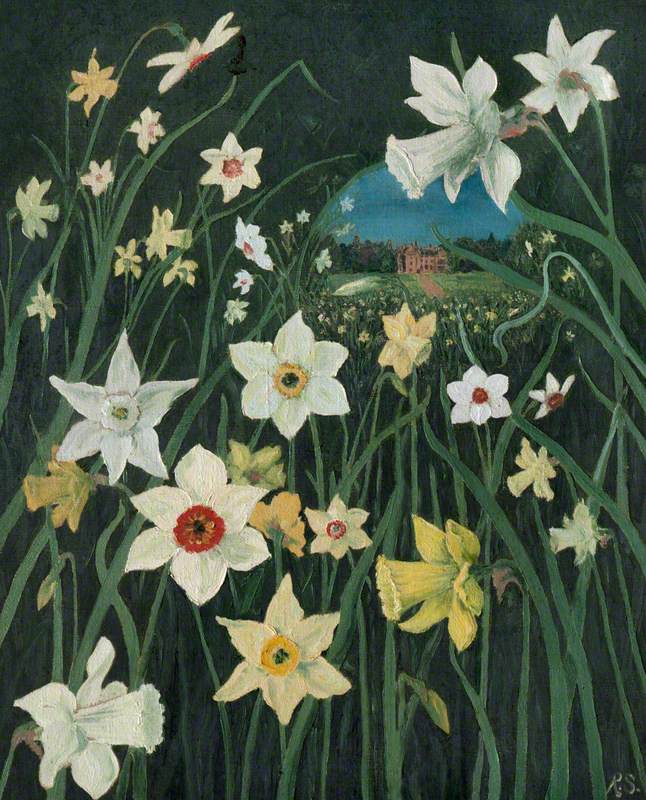

More intriguing than her technique, though, was her approach. Access to Amsterdam's botanic gardens and her father's floral specimens broadened her muse. Ruysch combined seasonal cut flowers with those that would have been in bloom many months before; just as she created the impossible in her father's display cases, so she painted it on her canvases.

In Ruysch's world, it was possible for late spring's poppies to drift alongside the summer trumpets of nasturtium. Zinnias, a late summer plant, erupt over fungi, traditionally autumn's harbinger, in A 'Forest Floor' Still Life of Flowers.

It's a riot of a painting – the plants seem to be reaching near-expiry, taking one last gasp of life before succumbing to the inevitable decay. But it's a nonsense scene: you will never find a ruffled-edge poppy or a sun-loving zinnia among the moss and murk of woodland.

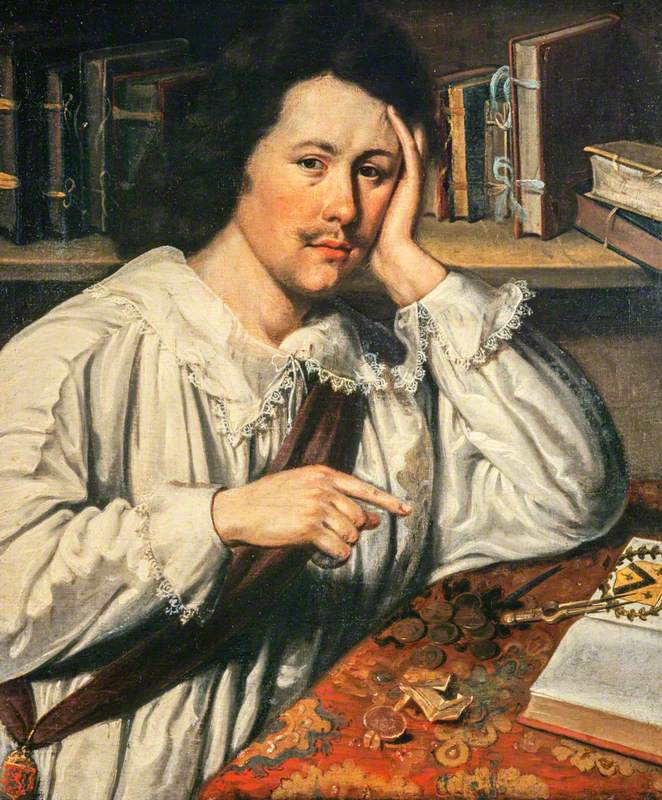

Of course, such pedantry didn't apply to Ruysch's popularity, which would have been considered remarkable even today. Her paintings commanded three times what Rembrandt's did. She was 29 when she married fellow painter Juriaen Pool and at the height of her powers. The previous year, Ruysch had sat for Michiel van Musscher, a portraitist who depicted her at work surrounded, intriguingly, by flowers that wouldn't have been in bloom at the same time (tulips, roses, Japanese anemones).

Rachel Ruysch

1692, oil on canvas by Michiel van Musscher (1645–1705) and Rachel Ruysch (1664–1750)

The 1692 portrait caused a stir when it was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art earlier this year; it holds a number of clues about an artist who hasn't always received the attention she deserves. We know she had ten children. We know she worked around them. We know she never gave up her maiden name. She painted until she died, nearly five decades later. On one of her last works, Ruysch inscribed her age: '83'.

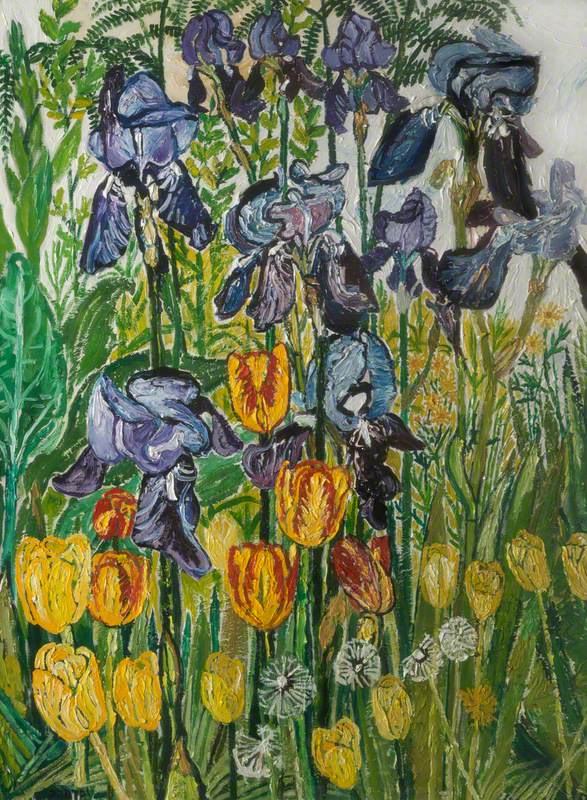

This was all hundreds of years ago, but Ruysch's works – and the great many they inspired – still feel keenly contemporary. As a gardener, I spy the seasons and the fallacy in Ruysch's arrangements but I also see a reflection of the globalisation we live in today, the one that was created by the colonialism and trading that ushered the Dutch Golden Age into being in the first place.

The bunches of flowers we buy now are Ruysch-esque: we grow cut flowers in greenhouses, we cover them in chemicals and we ship them in from far-flung lands. We have roses in December and tulips in September and we think nothing of it. We make our own fantasies, only we no longer know how to recognise them.

What we can learn, though, from these paintings is the art of artifice and the importance of decay. I rarely find a tulip more perfect than when it is on the cusp of falling apart, petals streaked like oil in a puddle. Ruysch, Bosschaert and that other great flower painter Jan van Huysum all knew this: they knew they were dealing with a fallacy, they knew that beauty is reliant upon impermanence. In a world constantly seeking lasting perfection, we'd do well to remember it.

Alice Vincent, writer and gardener based in London

'Dutch Flowers' is at The Box, Plymouth, from 7th October 2023 to 7th January 2024

This content was funded by the Samuel H. Kress Foundation