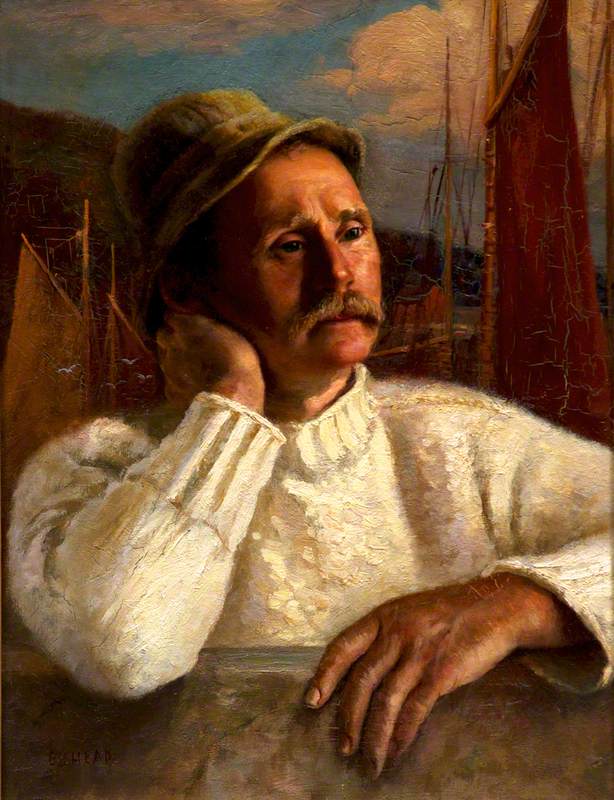

Up until the early twentieth century, the fishing industry thrived along the Pembrokeshire coastline, and up the miles of waterways that run through the landscape like veins. The Cleddau estuary, a confluence of four rivers, is a major part of this network. Rich in sewin, brown trout and salmon, commercial fishing has played a key role in its history and this way of life has been immortalised in the many paintings of fishermen at work.

However, relatively few paintings exist of the women who worked alongside them, and those few don't tell the whole story.

In W. F. Noble's The Fisherman's Wife, a woman is dressed in white with flowers blooming outside the window. She looks serene as she sits at home gazing out; a smile almost crosses her face. Little is known about the painter or the story behind the painting, which may have been Noble's intention, but this romanticised depiction undermines the role women played in the fishing industry. Her peaceful repose gives no insight into the long hours and hard, dirty work she would have done alongside her husband.

Ida Jones's Fisherman and Wife portrays a woman at work. We get a glimpse of her life and what she did to help feed the family while the fisherman himself stands nearby. Aside from household chores and caring for children, a fisherman's wife would have mended nets and baited lines in preparation for her husband setting sail. On his return, she would have cleaned and gutted the fish then headed to towns like Tenby and Haverfordwest to sell the day's catch.

The women who carried out these jobs and headed to market were often called 'fishwives' – 'wife' here being an old English term for 'woman' – but this word is now a gendered insult associated with bawdy women making crude comments, a caricature that devalues the work these women did. In fact, fishwives often needed to be loud to drum up custom, their perceived coarseness a way to gain attention and sell their wares.

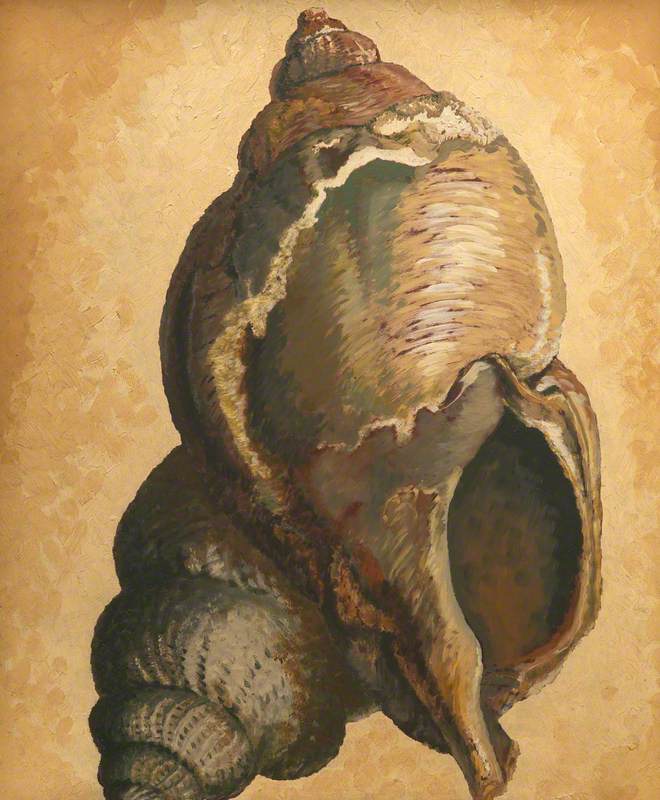

In Tenby Fisherwoman by William Powell Frith, from Scolton Manor Museum, we see a woman at work again, this time selling shellfish in Tenby. Although her autonomy is recognised by the title 'fisherwoman', the painting is likely misnamed. The woman pictured is now thought to be Dolly Palmer according to Dolly's great-great-granddaughter, Jane Smallfield, who has researched her ancestor extensively. Dolly sold her catch in Tenby but lived and fished in Llangwm, a small village situated on the Cleddau estuary, twelve miles from Tenby.

In the last decades of the nineteenth century, Llangwm was a busy fishing village and Dolly, like many other women from the village, was a skilled boatwoman. She owned her own boat and went out herself to fish for oysters in the turbid waters of the estuary. On returning to shore she would clean and pickle the shellfish then pack them into baskets for the long walk to towns like Tenby, Pembroke Dock and Haverfordwest to sell her wares.

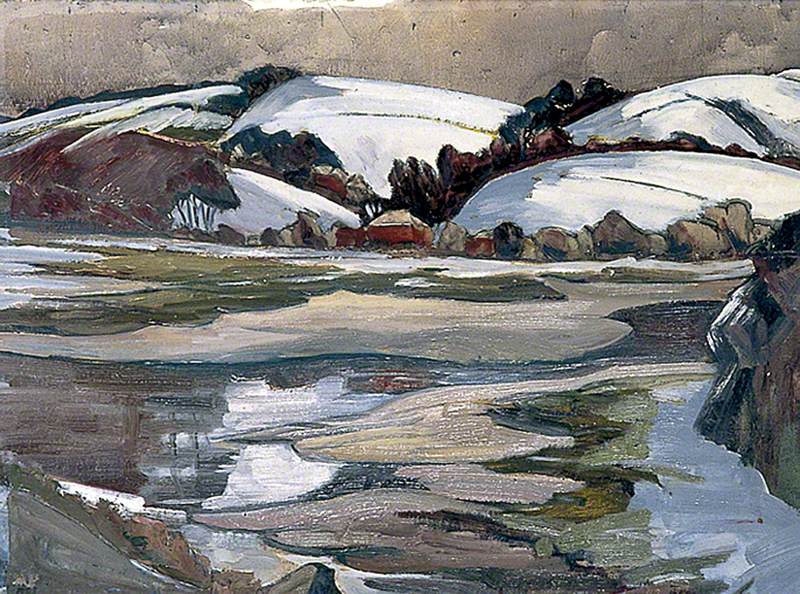

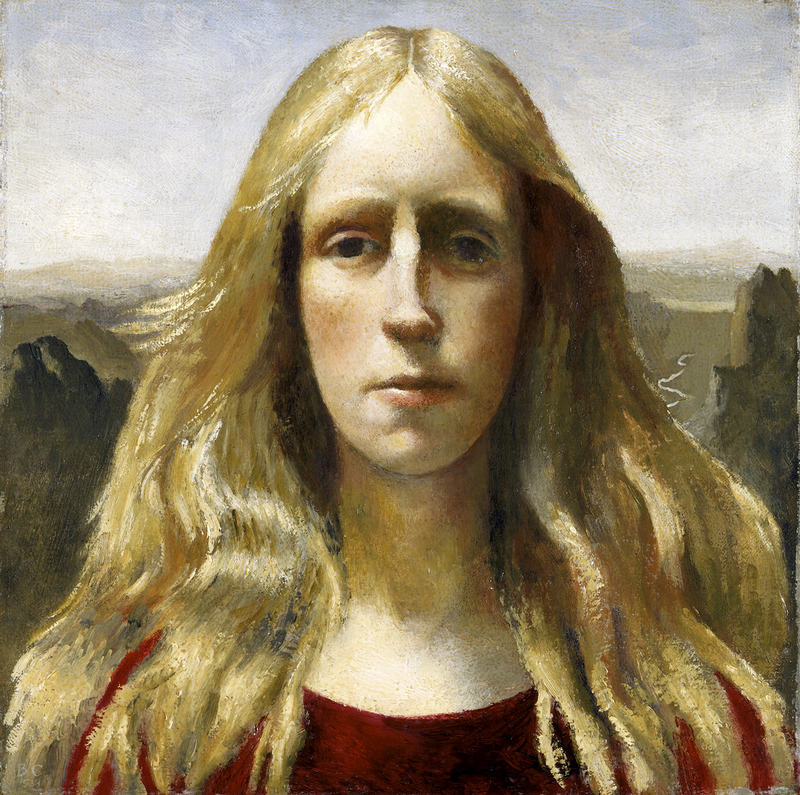

Perhaps she would even have been encountered by a young Gwen John as she wandered the streets of her hometown. Landscape at Tenby is one of the earliest known works by Gwen John, painted in 1896. Dolly would have been a familiar sight in Tenby at that time.

The fisherwomen of Llangwm wore distinctive clothing that included a black felt hat with a wide brim, heavy skirts and the red Welsh plaid petticoat, not unlike the traditional Welsh costume. This image and their unusual lifestyles made the women a tourist attraction and people from all over would visit the village to see the Llangwm fisherwomen, with news articles about them appearing as far afield as the USA.

Dolly was perhaps the most well-known. Her picture featured on postcards and boxes of chocolate while prominent photographers of the time visited Llangwm to take her picture – two of which are held by Tenby Museum.

At this time Llangwm was a matriarchy and the ability of these women to make a living on the shores of their home enabled them to remain in their village, not needing to leave to find work. They could also choose who they married and were able to continue working after marriage. In the 1881 census, it was recorded that 28 women in Llangwm were making their living as fisherwomen.

Dolly herself married and had at least nine children, with at least two of her daughters also becoming fisherwomen. She fished in Llangwm for 70 years, and at some point, it's said, she sold her distinctive outfit to a woman in Tenby. She retired in 1932 aged 90 and died the following year, having spent her entire adult life in her cottage by the shore.

Today Dolly and her fellow workers are well-remembered in the village. Evidence of their working lives is told in records and photographs but can also be seen in the midden piles that line the water's edge. These layers of crushed shells – lines of white in the muddy banks – are left over from the fisherwomen cleaning their oysters and cockles on the shore and serve as a reminder of the women's industry.

Midden Piles on Llangwm Riverbank

photograph by Lorna Snuggs

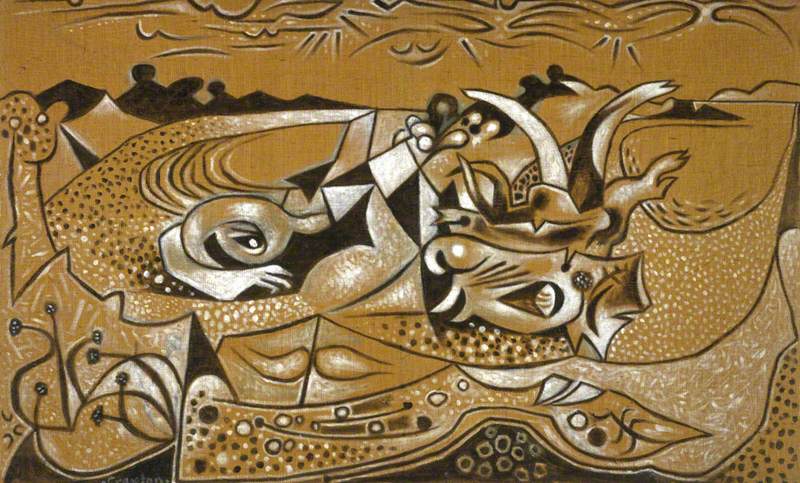

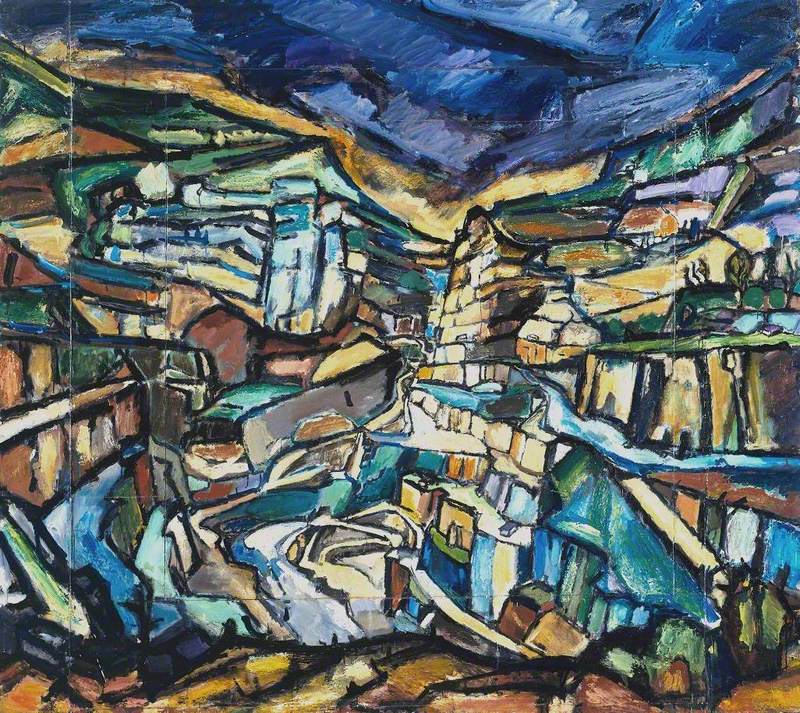

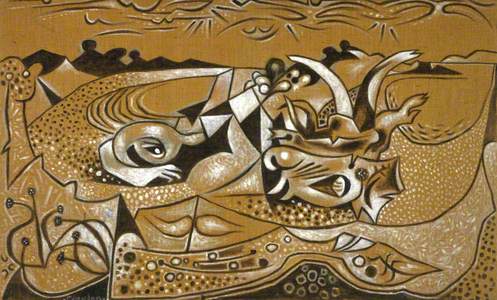

Eric Atkinson's Pembrokeshire prompts us to remember humanity's connection with nature, particularly in rural towns and villages where the historically close relationship is threatened. The colours highlight the contrast between land and water while the square shoreline hints at the dividing line between humanity and nature – yet they exist together.

The days of shellfish being caught by fisherwomen in the water by Llangwm are long gone and commercial fishing in the village has all but ceased although large numbers of native oyster beds remain in the Cleddau. However concerns around sewage levels and the diminishing numbers of oysters has meant the river, now a Special Area of Conservation, is the focus of new projects to improve sewage levels and encourage the return of the once plentiful oyster population.

Lorna Lee, writer

This content was supported by Welsh Government funding

For more, check out the Curations Tenby – A Portrait of the Sea and Women and the Sea on Art UK

Further reading

Margaret Brace (ed.), Llangwm: Captured in Time, 2022

David Evans (ed.), Pembrokeshire: Then & Now, Western Telegraph, 1988