Painted by Jan van Eyck in 1434, the 'Arnolfini portrait' is possibly the most debated portrait in European art history.

Portrait of Giovanni(?) Arnolfini and his Wife

1434

Jan van Eyck (c.1390–1441)

Speculation over the subjects of the painting has raged for hundreds of years, and there are extensive theories behind the purpose of this enigmatic double portrait. These debates have been outlined most recently by Carola Hicks and Jenny Graham, and an exhibition at The National Gallery traced the long-lasting influence of the Netherlandish painting on the work of the Pre-Raphaelites, 400 years after it was painted.

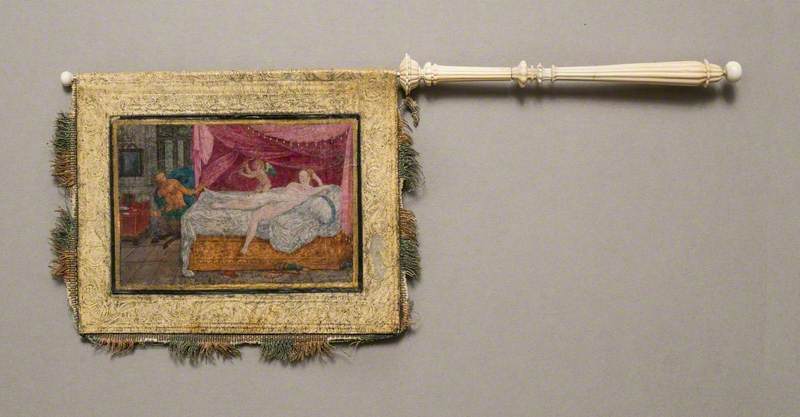

You can see a direct nod to Van Eyck's work in Dante Gabriel Rossetti's watercolour of the Italian Renaissance noblewoman Lucrezia Borgia – note the convex mirror in the background.

Edward Burne-Jones even called the Van Eyck painting 'the finest picture in the world'. Some of the latest arguments suggest the couple in the picture are the Italian cloth merchant Giovanni di Nicolao Arnolfini and his wife Costanza Trenta (who had died the year before), at their home in Bruges.

Amber Butchart wears the reconstructed dress in 'A Stitch in Time'

A BBC Studios production for BBC Four

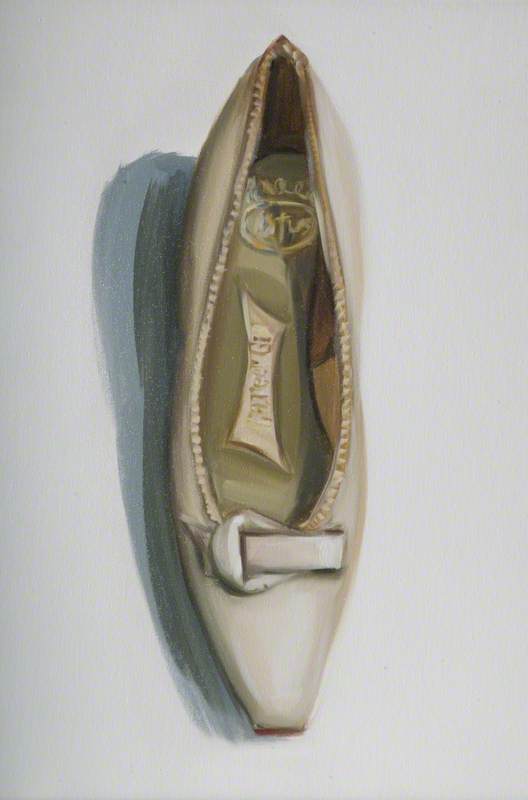

Examining the clothing in the portrait can help us glean new insights into this much-theorised artwork. What is undeniable is that the luxurious garments on display speak to the subjects' vast wealth. Medieval Bruges was a centre of commerce, with strategic links to northern European and Mediterranean trade routes, an area which has been called the cradle of capitalism.

As merchants, the Arnolfinis were at the vanguard of shifts in society that saw an element of mobility begin to develop. Riches could be achieved through trade and not just by accident of birth, which led to sumptuary laws in many European countries at this time. These laws were used to denote status in a society where mobility was feared, to clearly demarcate social standing as well as encourage domestic industry. Fur-lined, exquisitely dyed in vivid green, blue and deep black, the colours and fabrics on show all indicate the affluence of the Arnolfinis. The gown cascades on the floor in an ostentatious display of abundance. The fabric is a high-quality wool, the type of material that could even cost more than silk.

Amber Butchart wears the reconstructed dress in 'A Stitch in Time'

A BBC Studios production for BBC Four

It was the intense green of the dress, along with the complexity of the painting and the virtuosity of its rendering, that drew me to choose it for the BBC Four series A Stitch in Time. In the series we used an experimental archaeology approach to history, using the expertise and skills of historical tailor Ninya Mikhaila and her team to recreate garments from artworks to gain new insight through the process of making, while I explored the social history and context.

Thanks to The Mulberry Dyer I also got to try my hand at medieval dying techniques using weld and woad plants to create the sumptuous green colour – a process which is certainly not for the faint-hearted or scent-sensitive!

Amber Butchart and The Mulberry Dyer

Despite her appearance, the myth that the woman in the painting is pregnant has been debunked, and this is one of the key areas I was keen to explore. In 1841, the year before the Arnolfini portrait was bought by The National Gallery, a critic in literary journal The Athenaeum perpetuated the idea of pregnancy by implying a shotgun wedding, noting the woman has, 'one hand on her stomacher like a lady who had 'loved her lord' six months ere he became so'.

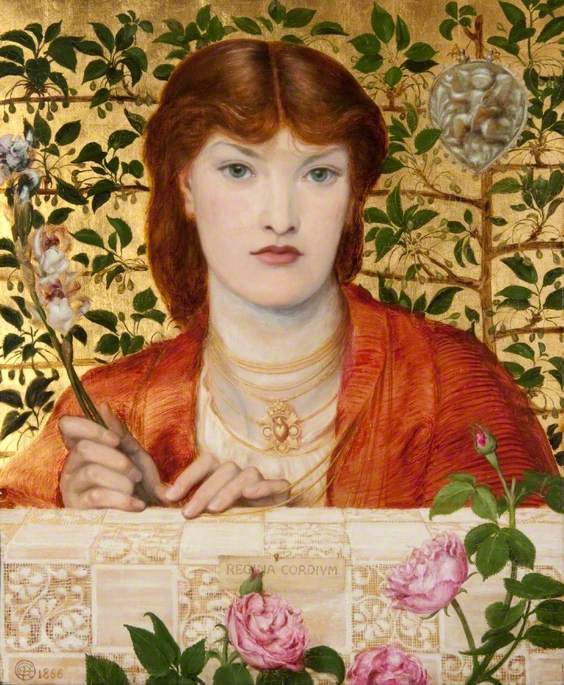

In her book on late Gothic European dress, the historian Margaret Scott explored the idea that the distended stomach was not a marker of pregnancy, but instead was an idealised female body which was present in contemporary images of saintly virgins as well as secular portraits.

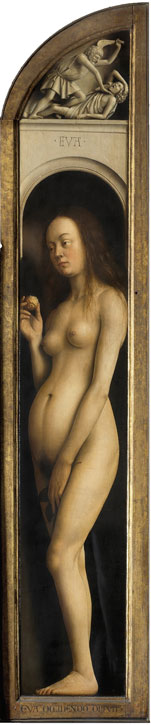

Eve from the 'Ghent Altarpiece'

c.1420s–1432, oil on panel by Hubert van Eyck (c.1385/1390–1426) and Jan van Eyck (c.1380/1390–1441)

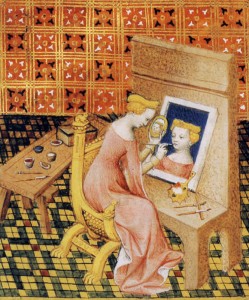

The unclothed idealised body can be seen in the image of Eve in the Ghent Altarpiece (also by Van Eyck, 1430–1432), as well as the depiction of the Garden of Eden by the Limbourg brothers (1411–1416).

'The Garden of Eden' from the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry

1411–1416, tempera on vellum by the Limbourg brothers (Herman, Paul, and Johan, active 1385–1416)

That women have been objectified and idealised throughout art history is nothing new. Art critic John Berger's book Ways of Seeing, based on his 1972 TV series of the same name, remains required reading at many art schools and universities. In it, he writes: 'Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves. The surveyor of woman in herself is male: the surveyed is female. Thus she turns herself into an object of vision: a sight.'

This oft-quoted passage chronicles the relationship between the gendered production of art and representation, an idea which crossed into film theory with Laura Mulvey's influential essay 'Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema'.

But the silhouette on show in these late medieval artworks appears unusual to our contemporary eyes, which are more accustomed to seeing the unattainable airbrushed bodies of fashion photography and advertising, and pictures on social media retouched with apps. Art historian Kenneth Clark drew aesthetic parallels between the 'long curve of the stomach' seen in fifteenth-century images, and 'the ogival rhythm of late Gothic architecture'. Scott calls this silhouette the 'Gothic ideal', placing it at odds with classically proportioned bodies, exemplified in art history by the Venus de Milo: a Hellenistic interpretation of classical Greek beauty.

Wearing the recreated Arnolfini gown reinforced the notion that the woman in green is not, in fact, pregnant. The weight of the swelling swathes of fabric make it difficult to walk freely, and holding the material up high – as she does in the painting – helps with balance and creates the stance that has become so recognisable from Van Eyck's portrait.

Before the industrial revolution, textiles were some of the most expensive, prized possessions a family could own. Re-made, re-worn or worn-out, they were bequeathed in wills and passed down through generations or on to servants. Parading such excessive fabric is a clear indicator of fortune and fashion, but crucially it does not indicate aristocracy – there is no precious cloth-of-gold, no expensive embroidery – this is not courtly splendour but mercantile riches transposed into fabric. As such, the painting is a masterclass in showcasing the wealth and status of the merchant Arnolfinis.

Amber Butchart, fashion historian, author and broadcaster