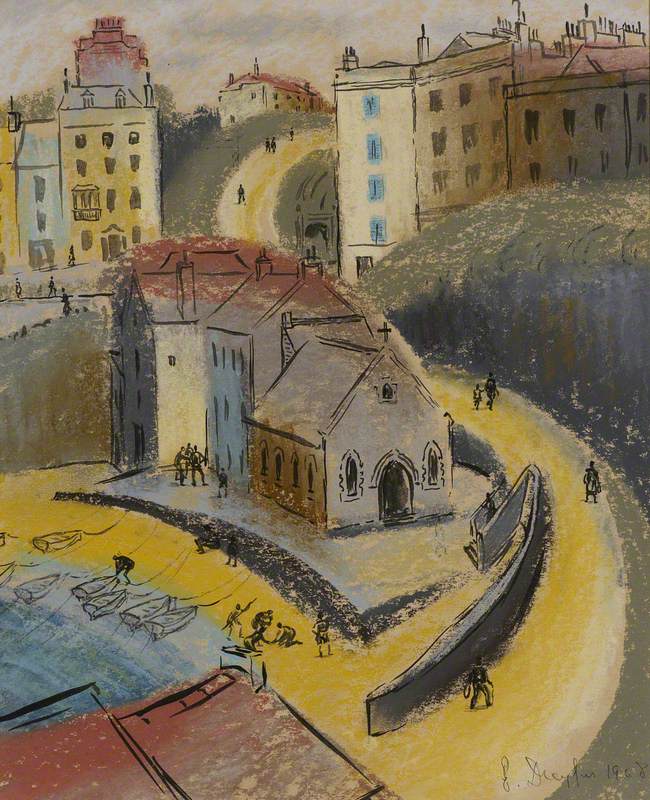

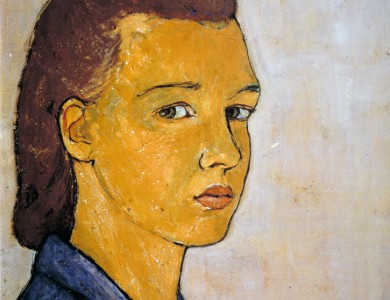

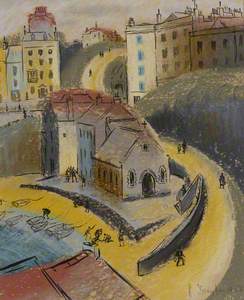

In the Ben Uri Collection is a remarkable double-sided piece, originally catalogued for the colourful pastel (recto) of a Welsh chapel (since identified as Tenby in Pembrokeshire, South Wales), signed by artist Enid Dreyfus, née Abrahams (1906–1972) and indistinctly dated, c.1968. It was presented to the Collection in 1986, some fourteen years after the artist's death, by Alice (Liesel) Schwab (1915–2001), a German-Jewish refugee from Nazism and collector of works by Jewish artists, following her retirement as Chair of the Arts Committee at Ben Uri Gallery.

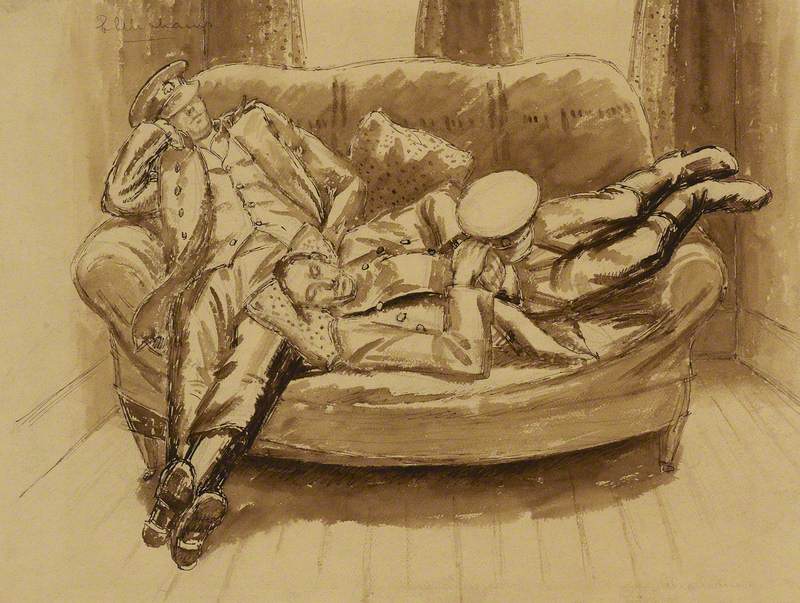

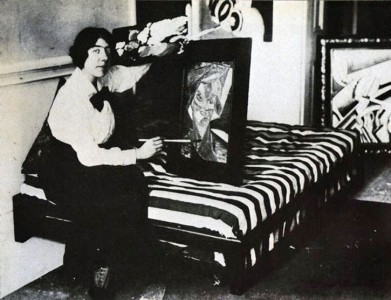

Archival research yields few traces of Dreyfus's artistic career, aside from a handful of reviews noting her participation in group exhibitions in 1956, 1967 and 1969. Yet, on turning the paper over, another image is revealed – a drawing, in landscape format, entitled Two Sleeping Soldiers (below), undated but clearly related to the Second World War. It is signed with the artist's maiden name, Enid Abrahams, and it was under this name that she built an extensive exhibiting profile between 1930 and 1944, particularly during the war years.

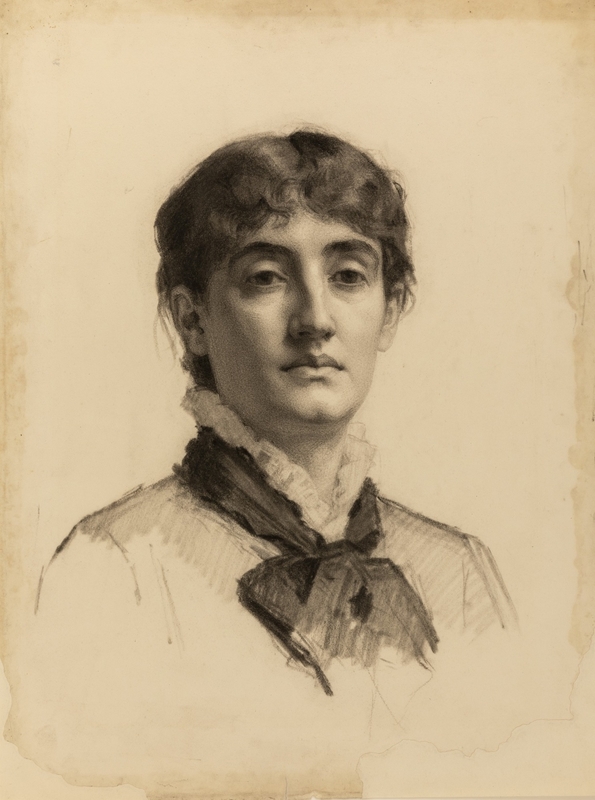

Born into a Jewish family in Hendon, north London, Abrahams studied at St John's Wood School of Art and the Royal Academy Schools. She then exhibited regularly at the Royal Academy and with artists' groups including the New English Art Club, the Royal Institute of Oil Painters and the Royal Society of British Artists, also showing on one occasion with the Society of Women Artists, and the London Group, respectively. In 1934, she participated in the latter's 32nd exhibition at the Burlington Galleries, where her still-life arrangement was praised by the Jewish Chronicle as an 'exceptionally attractive arrangement of colour and tone beautifully painted'. In other reviews, her pen-and-ink drawings were admired for their wit and character.

In the auxiliary fire service

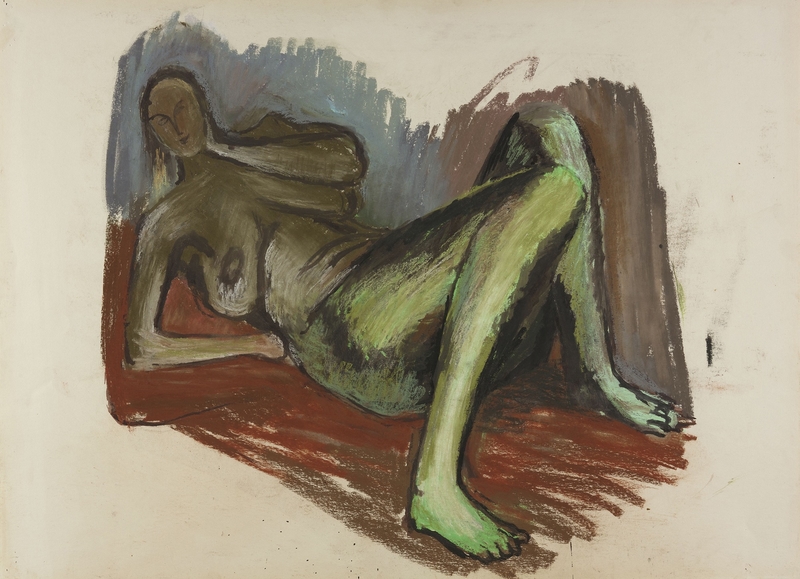

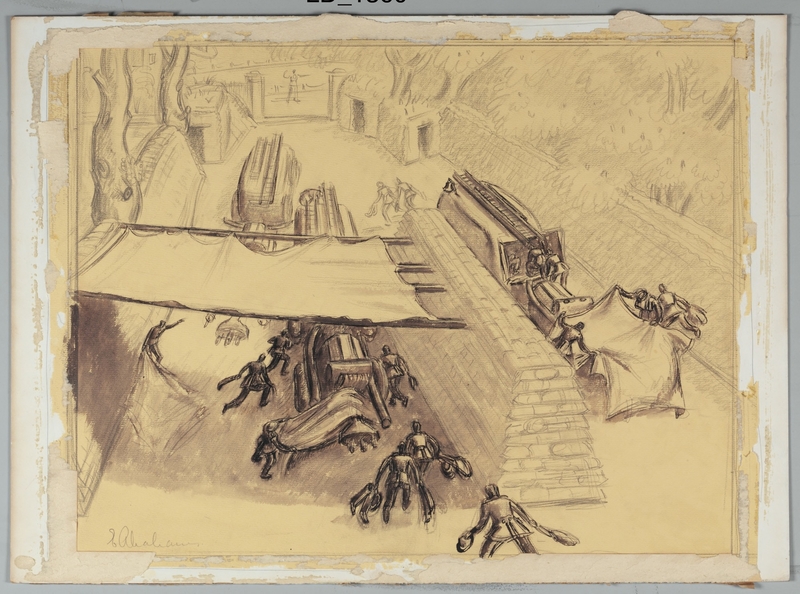

Following the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, Abrahams joined the Auxiliary Fire Service (AFS), part of the Civil Defence Service (superseded in August 1941 by the National Fire Service), as an unpaid local volunteer. Living in a flat in Abercorn Place, St John's Wood, she volunteered for the fire service in Hampstead and Bethnal Green, organised clubs, and drove a mobile canteen in Stepney. During her shifts, she sometimes sketched from life. Paints were limited and expensive during wartime and Abrahams used cheap, portable materials that were readily at hand, working predominantly in pen-and-ink and brown wash.

She had a keen eye for detail and for framing a composition. Her 'soldiers' (in reality, AFS firemen) share a sagging sofa that occupies the centre ground: one sleeps upright, leaning on his elbow, his cap tilted over his eyes, legs outstretched on the floor in front of him. The other lies prone, his head on a cushion against his companion's thigh, his hands crossed over his body and his boots thrust out over the arm of the sofa. The light visible through the opened curtains behind them indicates it is daytime and suggests they are sleeping, exhausted, after coming off night duty. Abrahams offers us a glimpse, at once humorous and humane, into the lives of those serving on the Home Front.

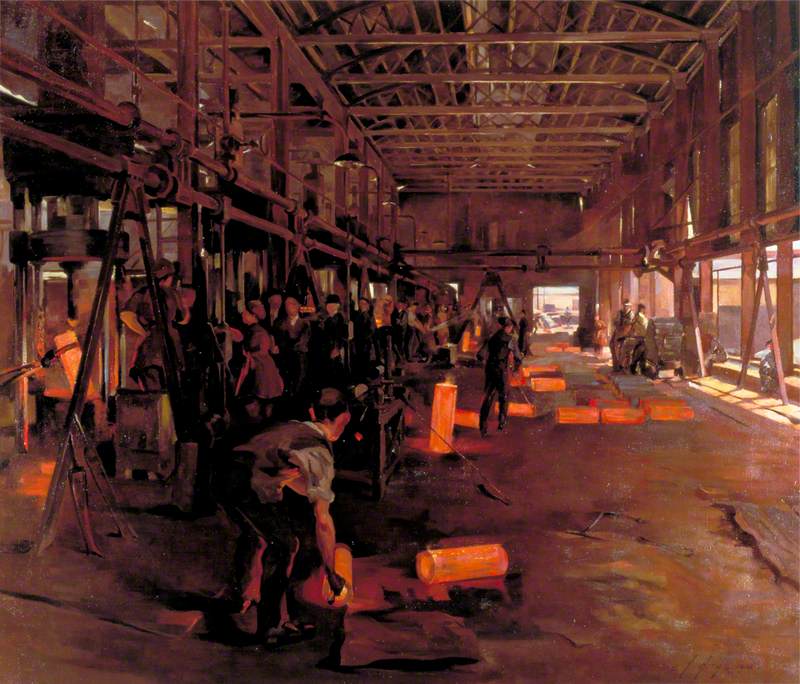

The Royal Air Force Museum, Hendon contains two further Abrahams' pen-and-ink sketches of AFS volunteers made during the London Blitz; equally witty and well observed, they employ a similar economy of means. The first, of AFS firewomen, may well be a companion to the Ben Uri drawing. It shows two firewomen sleeping soundly, top-to-toe in a narrow canvas bed in their quarters, against a backdrop of helmets and overcoats hanging behind them; no doubt, like the firemen, their sleep has been well-earned following their shift. The second, The Five Pound Piano – Firemen at Bethnal Green Fire Station, London Blitz, shows a lighter moment with a group of five firefighters during their break engaged in repairs to a wrecked piano. Abrahams recognised the value of entertainment in keeping up morale and, in 1945, she served as a make-up artist for an East End peacetime concert.

The Five Pound Piano – Firemen at Bethnal Green Fire Station, London Blitz

c.1941

Enid Abrahams (1906–1972)

She is also notable as one of the few women exhibitors – others included Julia Lowenthal (active 1915–1944), who like Abrahams worked principally in pencil and watercolour, and acting secretary Mary Pitcairn (active 1940–1945), an artist/novelist – who exhibited alongside their male colleagues in the hugely popular Firemen Artists' exhibitions. The women's work was often cited in reviews, if further down the newspaper columns.

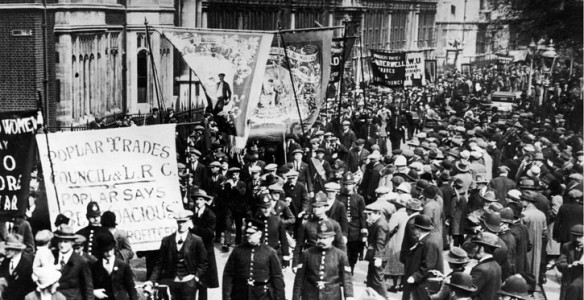

The Firemen Artists group was established in 1940 by ten artists serving with the AFS, who formed an Organising Committee and held their inaugural exhibition – the first of six London shows – at the Central School of Arts and Crafts the following March. Comprising over 100 paintings, it attracted 22,000 visitors in its three-week run. Works were admired for capturing both the heroism of the firefighters and the authenticity of their subjects, drawn partly from life and partly from memory. Kenneth Clark, Director of the National Gallery, and head of the War Artists Advisory Committee (WAAC), subsequently purchased three paintings for the government.

Bells! A Unit of the National Fire Service Answering a Call

Enid Abrahams (1906–1972)

Following this success, a second, larger and grander show was mounted at the Royal Academy in August 1941, from which one of Abrahams' drawings (now in the Imperial War Museum) was purchased for six guineas. It attracted more than 66,000 visitors; gradually tours were mounted to numerous towns and cities including Bradford, Brighton, Derby, Leicester, Oxford, Edinburgh and Glasgow. Some paintings were selected to tour to America, Canada, and even Australia, where they were offered for sale with at least half the proceeds supporting the AFS benevolent fund to assist fire workers' bereaved families. On two occasions, donations gathered at the free exhibitions went to the Red Cross and in 1944, with the exhibition again staged at the Royal Academy (and Abrahams again one of only three women participating), they went towards the rebuilding of the Queen's Hall.

In a 1943 edition of the NFS Firewomen's Magazine, Pitcairn summed up their collective achievements, as well as their popular appeal: 'Nor should it be forgotten that these pictures are the work of men who have had their ordinary service duties to carry out. Often rocking with fatigue, still covered with dust, with eyes smarting from smoke and hands still stiff from grasping branches, they came from high duty to their fellow citizens to serve posterity by their personal talents. Some were artists before the War. Some have become such by the inspiration of war-time conditions and scenes. But all at this time are, first and foremost, Firemen – and Firewomen – in a National Service.'

Women artists across the home front

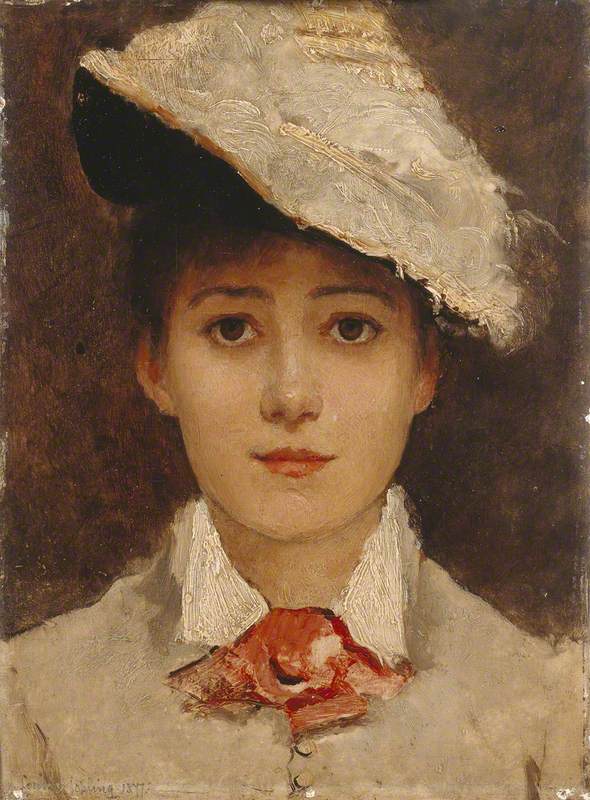

Beyond the fire service, Abrahams can also be considered as part of a wider group of women artists who documented war on the home front. They included Evelyn Dunbar (1906–1960), Rachel Reckitt (1908–1995) and Elsie Gledstanes (1891–1982). Gledstane's portraits of women include a Royal Naval Service Officer and three ambulance drivers, as well as others in a more traditional service role in The Dirty Plate.

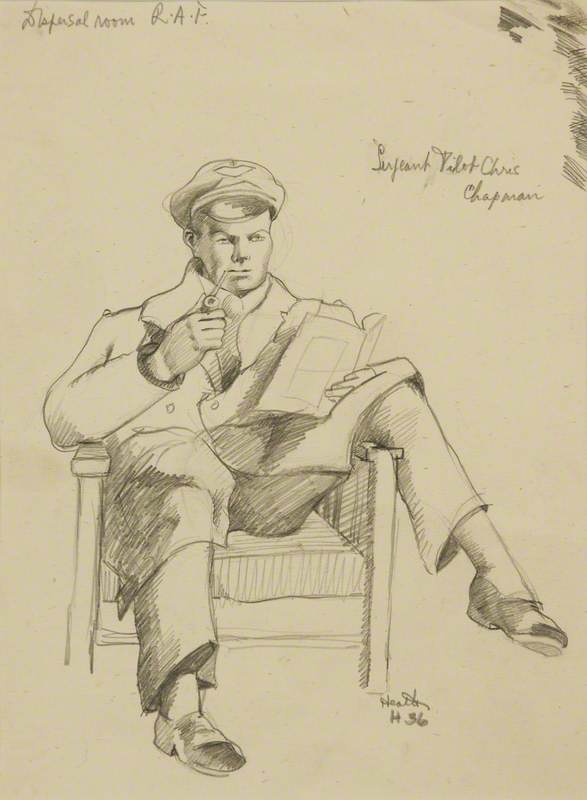

Sergeant Pilot Chris Chapman, RAF Perranporth

Isobel Atterbury Heath (1908–1989)

Isobel Atterbury Heath (1908–1989), commissioned by the Ministry of Information, painted women employed in munitions and camouflage at a factory in St Ives, Cornwall but also made informal naturalistic drawings, such as that of Sergeant Pilot Chris Chapman at RAF Perranporth.

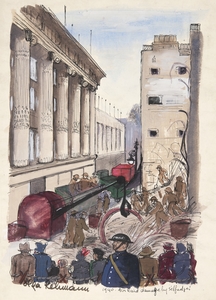

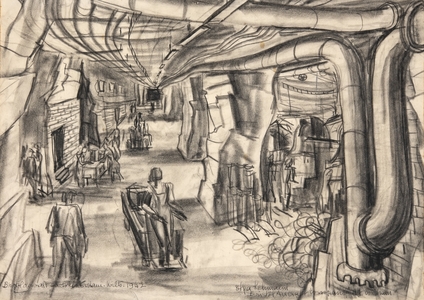

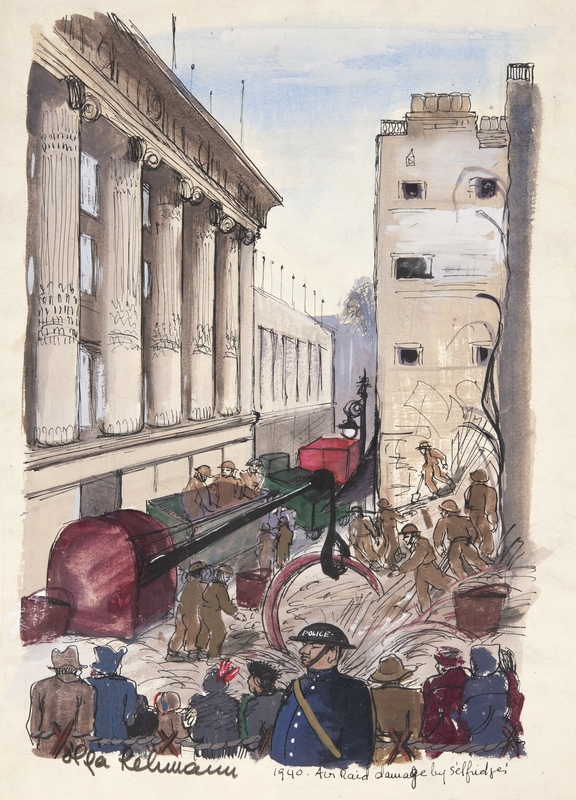

Air Raid Damage Opposite Selfridges, Oxford Street, London

1940

Olga Lehmann (1912–2001)

Chilean-born Olga Lehmann (1912–2001) produced numerous works on paper including a watercolour, gouache and ink sketch of police and auxiliary workers tackling raid damage outside Selfridges in Oxford Street, which still has an immediacy and freshness today. In her graphite Study for BAC Underground Factory, Corsham (1943), a study for the larger oil of the same name, she captures its cavernous interior, peopled by industrious female workers. She recalled: 'it was all supposed to be top secret, but I made little sketches in my sketchbook anyway. It all seemed endless, like an underground city… Here and there little electric vehicles hummed about, driven by girls at the helm, looking like ships' figureheads. They were all dressed in dungarees and wore their hair tied up in cloths of various colours.'

The wartime output of Dame Laura Knight (1877–1970), perhaps the most celebrated woman artist of her day, includes both pencil and watercolour preparatory studies for a commissioned oil of A Balloon Site, Coventry (VIII), to encourage recruitment of women RAF Balloon Command officers, capturing the balloons' uncanny quality as 'living things' and the skill of the women in managing them. Post-war, Knight became the only commissioned woman artist to attend the Nuremberg trials, where she made detailed drawings of Nazi prisoners in the dock in preparation for her celebrated commissioned painting in the Imperial War Museum.

Hospital Supply Depot at Roehampton Club

1940

Ethel Léontine Gabain (1883–1950)

Ethel Léontine Gabain (1883–1950), a painter and printmaker of French-Scottish descent, and founder member of the Senefelder Club to promote lithography, produced a series of four lithographs of Women's Voluntary Services members and four of child evacuees, six of them published in 1941 under the auspices of the Ministry of Information.

Her meticulous attention to detail is showcased in two contrasting lithographs: Hospital Supply Depot at Roehampton Club, a highly accomplished, if more conventional composition showing a group of uniformed nurses at work on sewing machines, and Ferry Pilots. This dramatic composition of two women of the Air Transport Auxiliary leaving Hatfield aerodrome in a Tiger Moth biplane, destined for delivery to trainee pilots, looks and feels more modern. Published in large print runs for British and American audiences, her lithographs were so popular that they were exempted from the usual wartime ban on luxury printing.

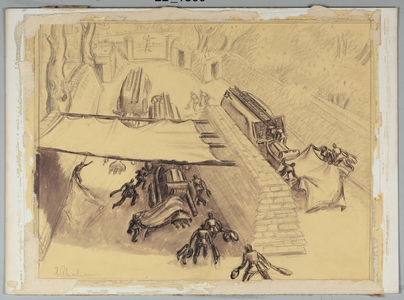

Untitled (Harbour Scene)

1940, pen & ink on paper by Katerina Wilczynski (1894–1978)

By contrast, Katerina Wilczynski (1894–1978), a Prussian-born refugee from Nazism, was one of many unofficial war artists. She sketched London buildings and landmarks damaged by bombing and contributed pieces to the war artists exhibition held at The National Gallery in around 1941, from which at least one was purchased by the WAAC. A rapid untitled sketch with two tin-hatted Home Guard or Air Raid Precautions wardens in the foreground is thought to depict the Royal Harbour, Ramsgate, which played a vital role in Operation Dynamo, mounted in May 1940 to rescue around 300,000 British troops from Dunkirk.

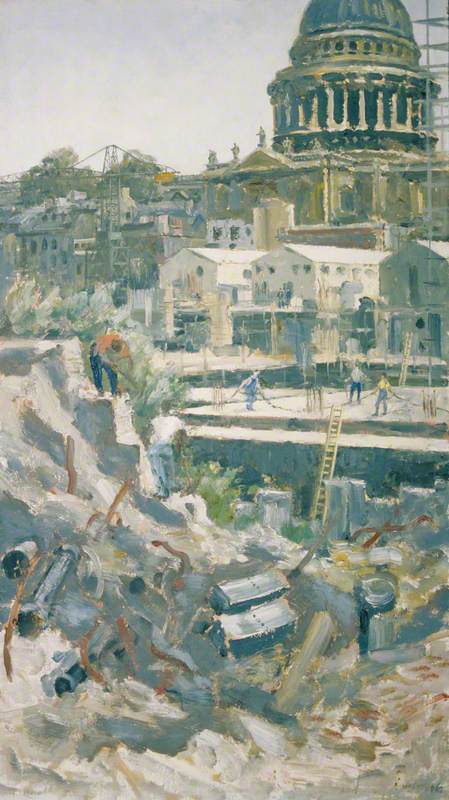

Enid Abrahams' own wartime works on paper received regular press attention, but post-war, probably following her marriage, her artistic output decreased, although in 1958 she was one of 34 women whose war work was remembered in a retrospective at the Imperial War Museum entitled 'Some Women Artists'. A later painting in the Guildhall collection references post-war reconstruction in the city near St Paul's.

The scarcity of Abrahams' works in public collections makes Ben Uri's rare, double-sided work on paper all the more remarkable and precious: her wartime drawing is a record not only of the firemen's part in the defence of the home front, but of Abrahams' own service, both as a firefighter and an artist. Moreover, the colourful pastel on the other side, executed in a breezy, joyful manner, a world away from wartime austerity, also allows us a glimpse into the later life and career of this little-known woman artist, whose lively wit is undiminished.

Sarah MacDougall, Director of Scholarship, Ben Uri Gallery and Museum

This content was funded by the Bridget Riley Art Foundation