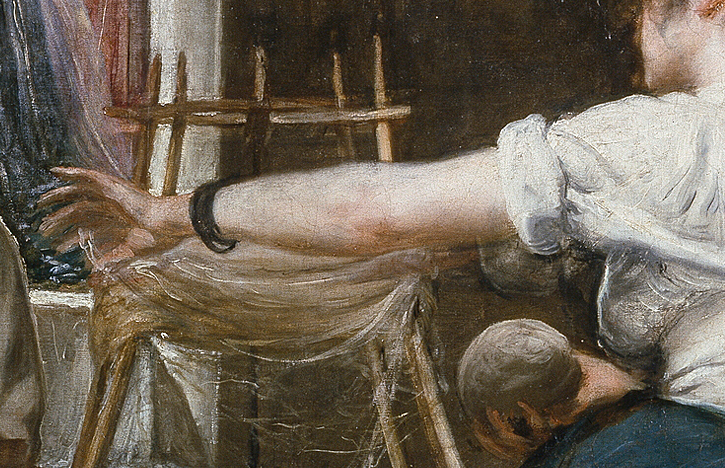

Diego Velázquez (1599–1660) possessed a remarkable technique in his use of oil paint, creating illusions of reality matched perhaps only by Jan van Eyck. In early works, he shares Van Eyck's sharp photographic realism that conceals the painter's brushwork. Later in his career, Velázquez employs strokes and daubs that the eye can easily discern, and which make for images of extraordinary vitality. In these works, he might be called the first great Impressionist.

Image credit: Museo Nacional del Prado, public domain (source: Wikimedia Commons)

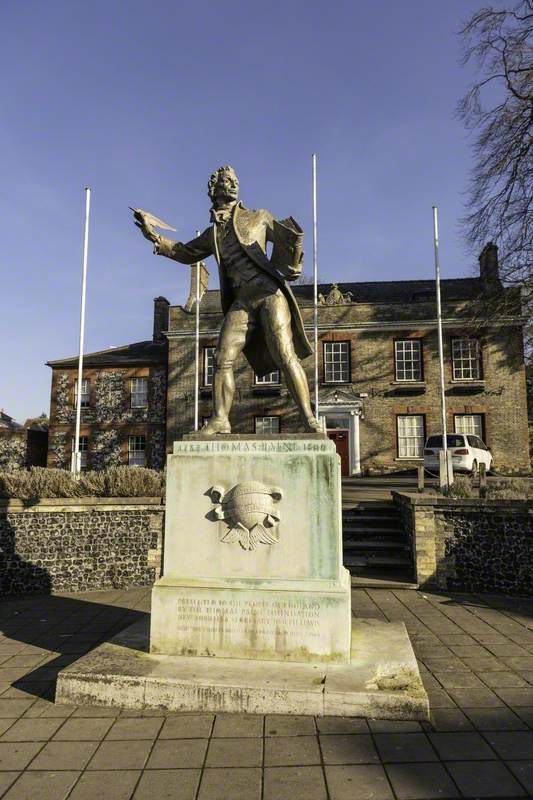

The Spinners, or the Fable of Arachne

(detail), 1655–1660, oil on canvas by Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

Kenneth Clark, urbane former director of The National Gallery, described moving backwards and forwards in front of Velázquez's late masterpiece Las Meninas, expecting to find a smooth transition from seemingly incomprehensible brushstrokes to recognisable reality.

Image credit: Museo del Prado, public domain (source: Wikimedia Commons)

Las Meninas

1656–1657, oil on canvas by Diego Velázquez (1599–1600)

Instead, the change was sudden and beyond his control. It was as if two different pictures existed. Clark hailed the truthfulness of Velázquez's art, and during the Second World War, Clark's idea to showcase one masterpiece from The National Gallery's collection drew crowds in their thousands to view Velázquez's The Toilet of Venus (popularly known as 'The Rokeby Venus').

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

The Toilet of Venus ('The Rokeby Venus') 1647-51

Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

The National Gallery, LondonAlong with The Rokeby Venus, The National Gallery houses several paintings by Velázquez. Elsewhere in the UK, there are works in a number of locations, such as the Wellington Collection in Apsley House, and the National Galleries of Scotland. The largest and finest single collection is in the Prado, Madrid.

Two Young Men Eating at a Humble Table c.1618–1620

Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

English Heritage, The Wellington Collection, Apsley HouseVelázquez's mastery allowed him to capture, with unparalleled veracity, the transitory moment: the droplets that drip down a fat jug, the blurring motion of a spinning wheel and a spinner's flickering fingers, or the hardening of frying eggs in a pot of hot oil.

Image credit: National Galleries of Scotland

An Old Woman Cooking Eggs

(detail), 1618, oil on canvas by Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

We see these astonishing effects in three of Velázquez's most celebrated paintings – An Old Woman Cooking Eggs (1618), The Waterseller of Seville (c.1620) and The Fable of Arachne (1655–1660). These paintings cover almost the whole span of his working life, and trace a development towards ever greater freedom in the handling of paint – a trend seen in the careers of many other artists, notably Titian, an artist Velázquez particularly admired.

From Van Eyck's exact art to Titian's sketchy exuberance, Velázquez had a chance to view these two artists' works in Madrid, where Van Eyck's Arnolfini Portrait was in the royal collection, along with Titian's Rape of Europa and Diana and Actaeon.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

Portrait of Giovanni(?) Arnolfini and his Wife 1434

Jan van Eyck (c.1390–1441)

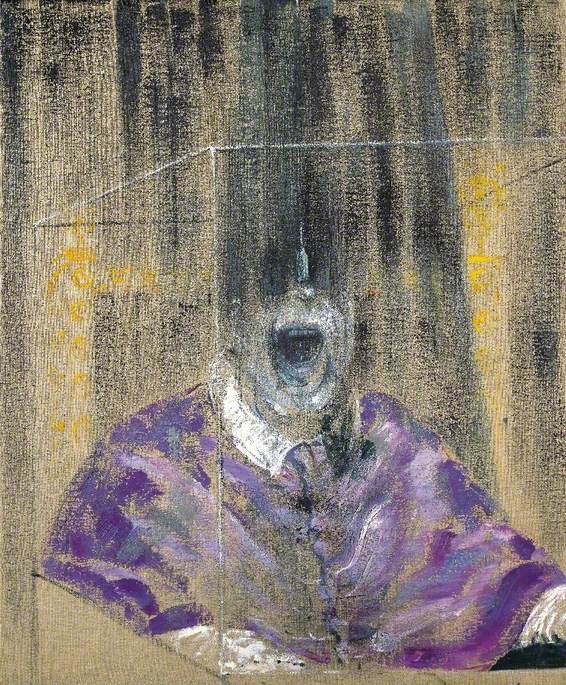

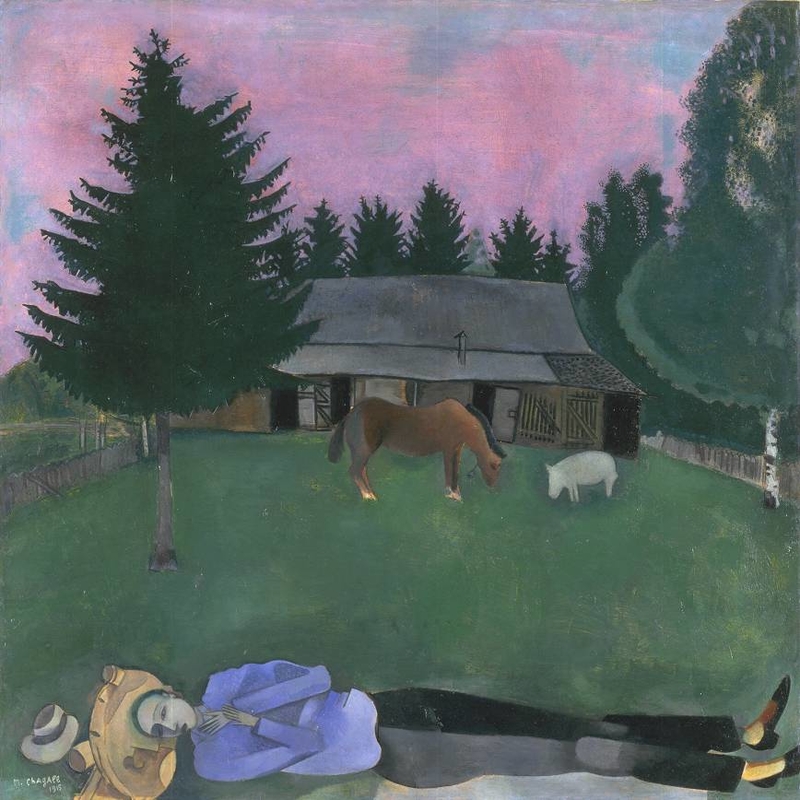

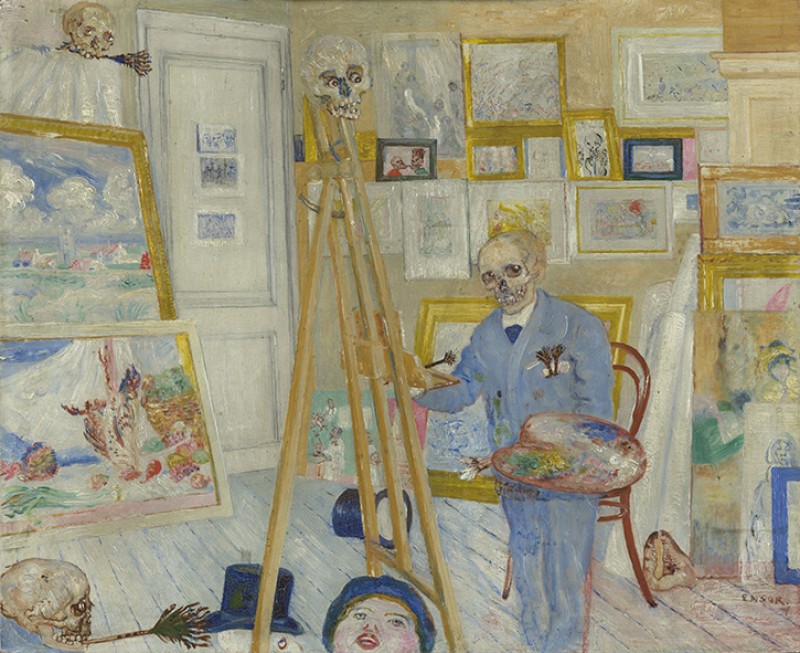

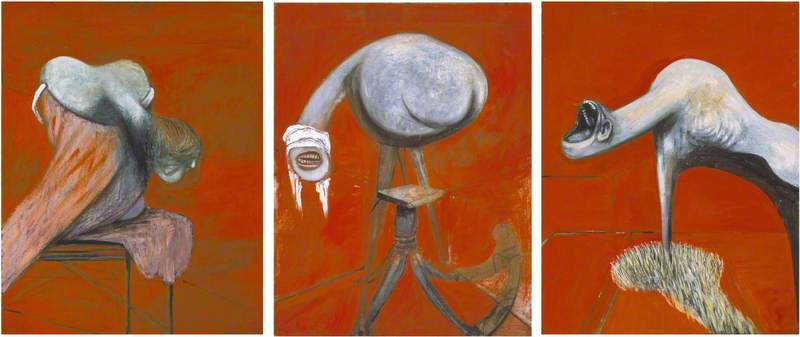

The National Gallery, LondonIn the twentieth century, Francis Bacon's 'obsession' – as he put it – with Velázquez's expressive effects and use of colour, led to a series of so-called 'screaming Popes' based on Velázquez's Innocent X.

In an interview with David Sylvester Bacon would later express his disappointment with these works, judging them unsuccessful and as 'stupid things [he] had done' with the venerated Velázquez.

What Velázquez and Bacon have in common, however, is sheer passion in using paint and the effects it can create. In Velázquez we see many examples of what Jonathan Brown calls in his 1986 book his 'ostentatious demonstrations of painterly skill'. And it must seem, for the possessor of such skill, justification enough to wield the brush in making ever more challenging illusions come to life.

To paint a convincing image of fried eggs is one thing: getting the white right, the suitably golden yet natural-looking yolk, the glistening surface, the ragged irregular edge. But to choose to show the egg in the process of cooking, before it assumes its cooked state – captured in its moments of transformation – that is something special. To think this worth doing is to trust in a rare and bold technique. But how does this work in the painting?

It is a strange image: the two figures, young and old, do not connect. Their eyes look anywhere but at each other. The alchemy in the pot between them goes unseen. And there is an unseeing air to the old woman's gaze, a rheumy quality that the sliding eggs somehow relate to: and the eggs themselves are a pair of eyes staring anywhere but at the protagonists.

The objects in this painting have been deliberately chosen, it is suggested, to allow the artist to show off his skill in depicting a variety of forms and surfaces: reflective metal alongside dull pottery, the hairy bulb of garlic and the jelly-like albumen of the eggs.

In this respect, Velázquez shares a proud awareness of his gift with Van Eyck, whose works are replete with challenges – brilliantly met – to his painterly skill. Indeed, Van Eyck is so keen for us to recognise his authorship that he signed his probable self portrait (known as Portrait of a Man) 'Als Ich Can' – As I can – which can be read as either a hint of false modesty or a declaration that he alone was able to create such a lifelike image.

Velázquez's realism is combined with the artist's willingness to bend the rules: as Brown points out, the assembly of kitchenware is tilted unnaturally towards us so that we can see inside. How else would Velázquez show off the uncanny shadow of the knife, the knife that has just stopped rocking?

Velázquez does not hesitate to distort angles. Famously The Rokeby Venus defies physics – it is her waist and hip we should see in the mirror, not her hazy face.

Image credit: The National Gallery, London

The Toilet of Venus ('The Rokeby Venus') 1647-51

Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

The National Gallery, LondonIn The Waterseller, we find more gazes that do not meet. And the boy appears again, the same boy, just as sullen, and a little older.

The Waterseller of Seville c.1620

Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

English Heritage, The Wellington Collection, Apsley HouseThis is an image full of stillness: the impeccable glass of water is full to the brim, and both the boy's and the seller's fingers are upon it, as if to stabilise it, to keep it level. Stillness keeps it from spilling.

Image credit: Historic England Archive

The Waterseller of Seville

(detail), c.1620, oil on canvas by Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

A subtle echoing of the lines on the water jug in the wrinkles of the seller's brow gives the seller the solidity of stone. His arm and hand resting on the jug handle form a heavy, anchored pyramid, and a suggested arc from forehead to pot makes the assemblage cohere. Indeed the seller's body seems as one with the stout jug, as if his body emerges from it.

In minute contrast to these still, stable elements are the exquisitely painted water droplets on the side of the jug. Some still adhere to the pot, about to weep down its sides; others have made their journey, leaving a trail that darkens: thus their movement is portrayed in its two phases.

A work from the end of Velázquez's career, The Fable of Arachne, has passages of sketchy impressionism that remind us of the late works of the much revered Titian.

Image credit: Museo Nacional del Prado, public domain (source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Spinners, or The Fable of Arachne

1655–1660, oil on canvas by Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

Indeed homage is paid to the great Venetian in the background of this picture, where a tapestry of his Rape of Europa (1560–1562) hangs, half hidden by five figures. Titian's painting was in Madrid in Velázquez's lifetime, where he doubtless admired it.

The story of Arachne tells of a spinning contest between the very human and ultimately boastful Arachne and Pallas Athena, goddess of arts and crafts. Pallas wins and turns Arachne into a spider. Scholars disagree on the identity of the foreground figures, who are either seen as anonymous weavers or as the fabled protagonists at work: Pallas disguised as an old woman in the left foreground and Arachne to the right. It is this woman's left hand that we focus on.

Image credit: Museo Nacional del Prado, public domain (source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Spinners, or the Fable of Arachne

(detail), 1655–1660, oil on canvas by Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

Such is the speed of Arachne's work that her fingers blur and appear to split and even multiply. It reminds us of another hand by Velázquez: that of the Infanta in Las Meninas (1656), which is also impressionistically rendered, suggestive – despite her serene disposition – of restlessness and nervous energy.

Image credit: Museo Nacional del Prado, public domain (source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Spinners, or the Fable of Arachne

(detail), 1655–1660, oil on canvas by Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

The tour de force of the Fable, however, is the spinning wheel.

A belief expressed by art historians, for example, Jan Baptist Bedaux, is that depicting motion in art is a sign of the highest accomplishment – the apogee of realism. Artists since classical times have attempted this difficult illusion.

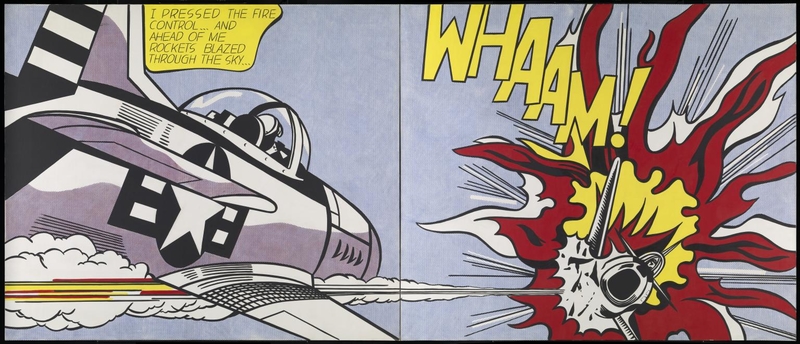

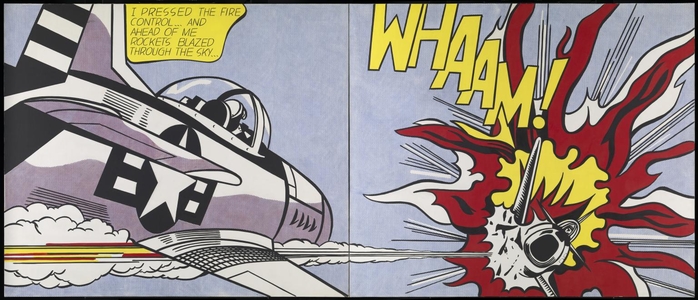

Twentieth-century artists such as Marcel Duchamp, Kazimir Malevich, Natalia Goncharova and the Futurists suggest it through stop motion-type staging of action or radiating lines. While on a cruder level, cartoonists use motion lines, a technique aped by Roy Lichtenstein in his Pop Art creations based on comic strips.

Velázquez, 300 years earlier, achieved a persuasive picture of a high-speed wheel by direct imitation, which surpasses all these experiments in its realism. Jonathan Brown's 1986 description is as good as any:

'...a whirring wheel, the spokes of which fuse into a blur of motion. Velázquez nurtures this sublime effect by placing soft, vaporous highlights within the circumference to suggest the play of fugitive reflections on the nearly transparent surface'.

The Fable of Arachne is about transformation and transience – in the work the women do, turning fleece to yarn to woven tapestry, and in the way the painting slides from passages of relative solidity to areas of indistinct, almost gaseous haze. Contrast the indistinct head and face of the woman in the centre with the relatively sharply drawn sections of the framework. Even the figures standing in the background seem to merge with the tapestry hanging there, so that we may see the figure in armour and the woman facing him as woven into it. Likewise, the cherubs might actually be flying over their heads.

Image credit: Museo Nacional del Prado, public domain (source: Wikimedia Commons)

The Spinners, or the Fable of Arachne

(detail), 1655–1660, oil on canvas by Diego Velázquez (1599–1660)

These examples of Velázquez's virtuosity, among the countless others in his works, are the artist's alchemy. The waterseller's gold is water, the exemplary liquid. Yet that glass of water has become a hard crystal, as hard as a jewel. We are reminded of its liquidity in those migrant droplets. The tool of the spinner, the wheel, an object of wood, has melted into the air, and is now a ghost. And what better food to choose than cooking eggs to demonstrate your magical power to capture brilliantly that everyday transformation?

Velázquez is showing off – showing us what he can do. There need not be any other urge to paint.

Adam Wattam, writer

Further reading

Jonathan Brown, Velázquez: Painter and Courtier, Yale University Press, 1986

Jonathan Brown, Collected Writings on Velázquez, Yale University Press, 2008

Giles Knox, The Late Paintings of Velázquez, Ashgate, 2009

David Sylvester, Interviews with Francis Bacon, Thames & Hudson, 1980