Sandra Blow (1925–2006) was a committed abstract painter. Yet her work and life were profoundly shaped by the tangible, phenomenological experience of place. In different ways, the urban infrastructure of London and the expansive environment of Cornwall infused Blow's exploration of colour, form, composition and material. Alongside producing paintings in the capital for over four decades, she also developed an important connection with Cornwall in the 1950s. Later in her career, Blow relocated permanently to St Ives, a shift in perspective which prompted a burst of large-scale, elemental canvases. Blow's responses to these sharply contrasting sites, however, were consistently linked by her innovative use of collage.

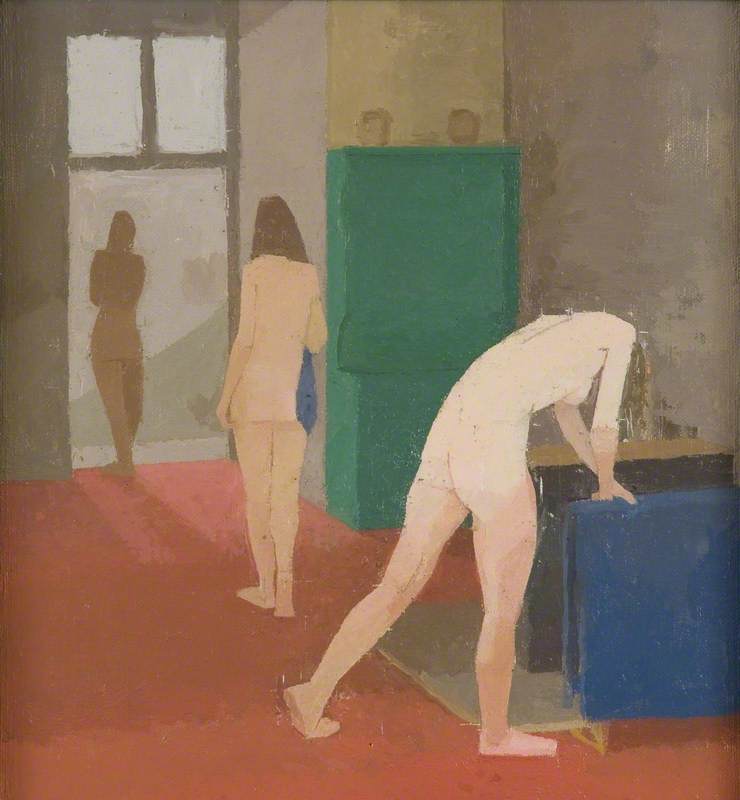

Blow was born in North East London in 1925 into a Jewish family. Her father, Jacob Blow, had inherited a wholesale fruit business based in Spitalfields market, and her mother Lily's parents also worked in the trade. Lily's sister Rose was to prove an important influence, supporting her niece's application to study at St Martin's School of Art, where Blow was accepted at the young age of 15 in 1941. Blow studied there for five years, producing life-drawing and portraits, while immersing herself in Soho's wartime social scene. Having enjoyed St Martin's, Blow enrolled for further study at the Royal Academy Schools in 1946, but found the experience stifling. At the end of the summer term in June 1947, she left to travel around Europe on what became an extended and pivotal journey.

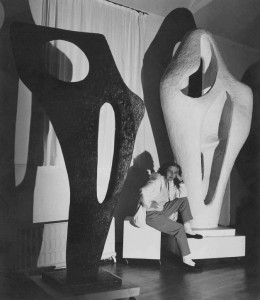

In Rome, Blow befriended a group of Italian and American artists and decided to stay for a year rather than returning to the RA, instead soaking up another important environmental influence: Renaissance art and architecture. Blow also met the Italian abstract painter Alberto Burri (1915–1995), beginning a relationship which turned into a lifelong friendship. Back in London, Blow sought to distil everything she had encountered and experienced in Italy, increasingly pushing her practice into abstraction.

Two Figures (1954) manifests Blow's painterly trajectory during this period: the titular evocation of two personages breaks down into complex tessellating areas of pattern and colour-contrast, moving between intricate arrangements of red, orange, brown, cream and black.

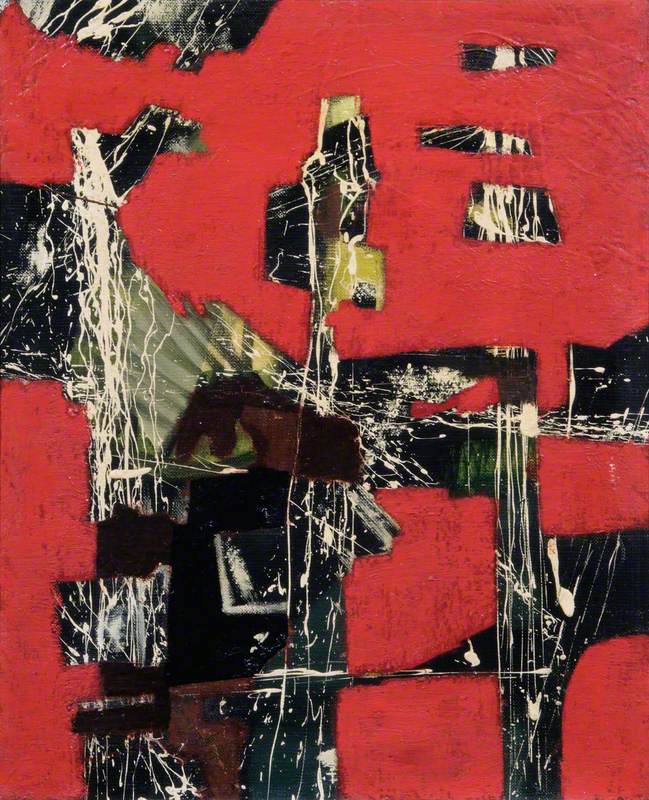

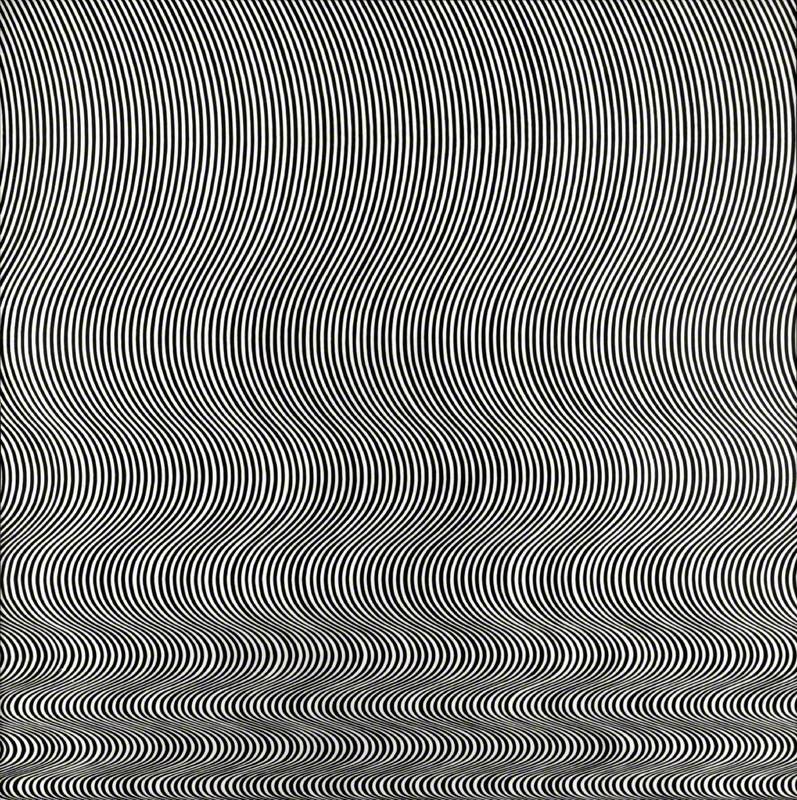

By the mid- to late 1950s, as both Painting (1957) and Untitled (1958) indicate, Blow's titles – and the canvases themselves – no longer refer to content. In Painting, the composition focuses on textural interplay between collaged sections of rough-looking material and areas of scumbled pink and red paint, which glow vividly against the dark background. As both works make clear, while Blow is primarily associated with oil and acrylic, her canvases often comprised layers of materials and collage – the scuffed surface of Untitled, for example, has been generated using sand.

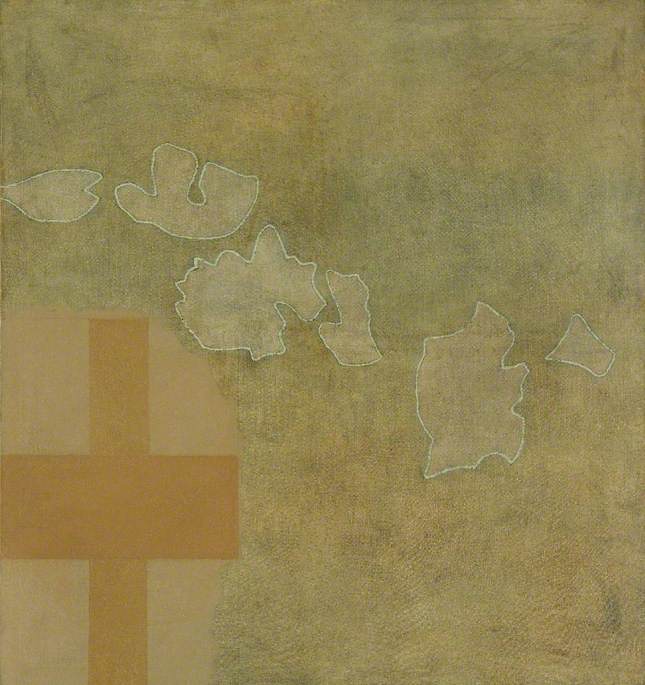

To make Space and Matter (1959) – acquired by Tate and as a result one of Blow's most recognised works – the artist combined oil paint with liquid cement and fragments of chaff. This mixture resulted in a dynamic compositional terrain which conjures a dramatic weather event: water, rock, air and wind crashing together. The materials give the work an intensely tactile quality, evoking organic matter including grasses, but also fur and hair.

This formal experimentation with textiles, from mattress-ticking and sacking, to tea and ash, links Blow's paintings to the substances of everyday life. Blow often lived in her studios, and the paintings are indexed to the biopolitics of everyday life and its rhythms, from sweeping the grate after a fire has died away, to preparing a warm drink.

As the presence of chaff in Space and Matter indicates, Blow found the organic in the urban, explaining in a 1994 interview with Sarah O'Brien Twohig: 'I love London skies, because they are framed and one sees them almost like a painting. I'm often amazed at the juxtapositions of trees, parts of buildings and the sky, and constantly changing, subtle colours.' Yet Blow's time in Cornwall also influenced her engagement with materials, particularly sand in works such as Untitled and Abstract Composition (1961). In 1957, Blow met the Zennor-based abstract artist Patrick Heron (1920–1999) through her friendship with the artist Roger Hilton (1911–1975). Heron invited Hilton and Blow to stay at his home at Eagles Nest. While there, Blow decided to rent a cottage near Heron's house at Higher Tregerthen, staying there for a year.

While the sand in Abstract Composition links it to Cornwall's coastal landscape, the finely dispersed granular spray of grey, cream and black particles also creates an effect that swings between microscopic particles suspended in a solution, and the constellatory vastness of the cosmos. This aspect of Blow's work has affinities with that of abstract painter Prunella Clough (1919–1999), who Blow respected a great deal, referencing the sustaining nature of their conversations over the years in an interview with critic Andrew Lambirth.

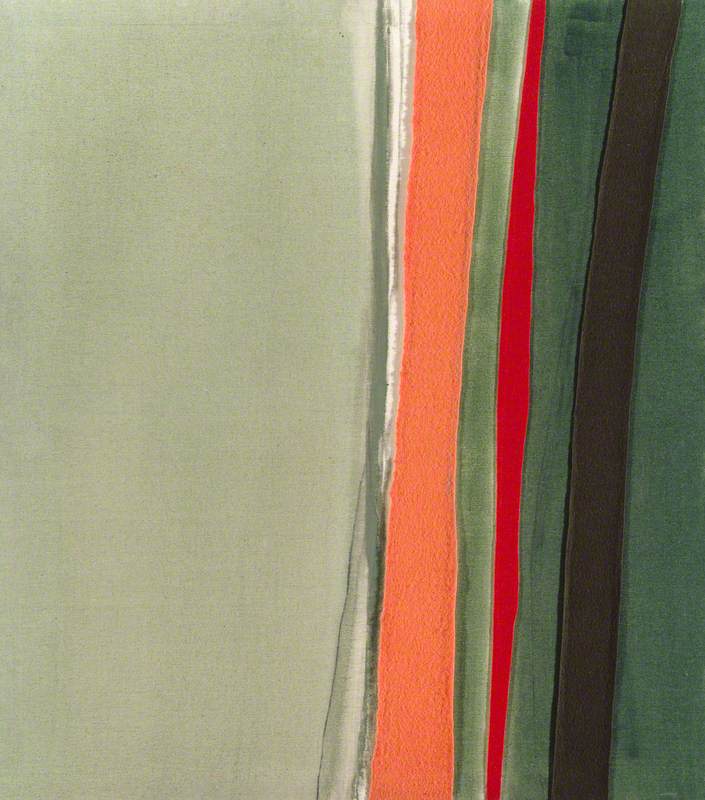

During the 1960s and '70s, Blow worked on an increasingly large scale, responding to the sense of openness she found in Cornwall and also her long-standing interest in how London's architecture frames the urbanite's view of the sky. Works such as Green and White (1969) continue to deploy collage materials, combining strips of paper with soft washes of ash, which bisect a vivid acid-green plain. Blow's concern with the bold, schematic division and organisation of space informs the large-scale canvases she produced during these decades, which led to her election to the Royal Academy, and inclusion in major exhibitions such as the 1978 Hayward Annual. From 1961–1975, Blow also taught at the Royal College of Art.

The 1978 Hayward Annual was significant because, unlike many group exhibitions at the time, it was selected by a group of five women artists (Rita Donagh, Kim Lim, Liliane Lijn, Tess Jaray and Gillian Wise Ciobaratu) and consisted of more women than male exhibitors. The press response veered from the hostile to the condescending, reflecting the art world's deep-seated misogyny. Equally, as the feminist art historian Griselda Pollock argued, the show did not develop from explicitly feminist politics – although it did include practitioners involved in the feminist art movement, such as Mary Kelly.

Blow was, in this respect, representative of Pollock's critique that many of the women in the show were successful according to the art world's terms (at this point she was already a Royal Academician). Yet Blow's involvement in the second Hayward Annual in 1978 underlines how her work was still caught in the gendered inequalities of the art world, from her experience of sexism at the Royal Academy Schools, to the insistent critical comparisons over the years between her work and Burri's, despite their very different formal effects.

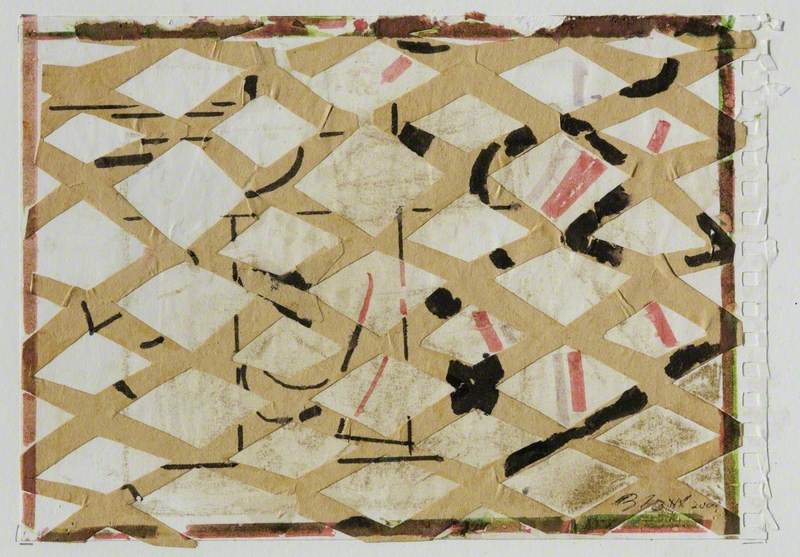

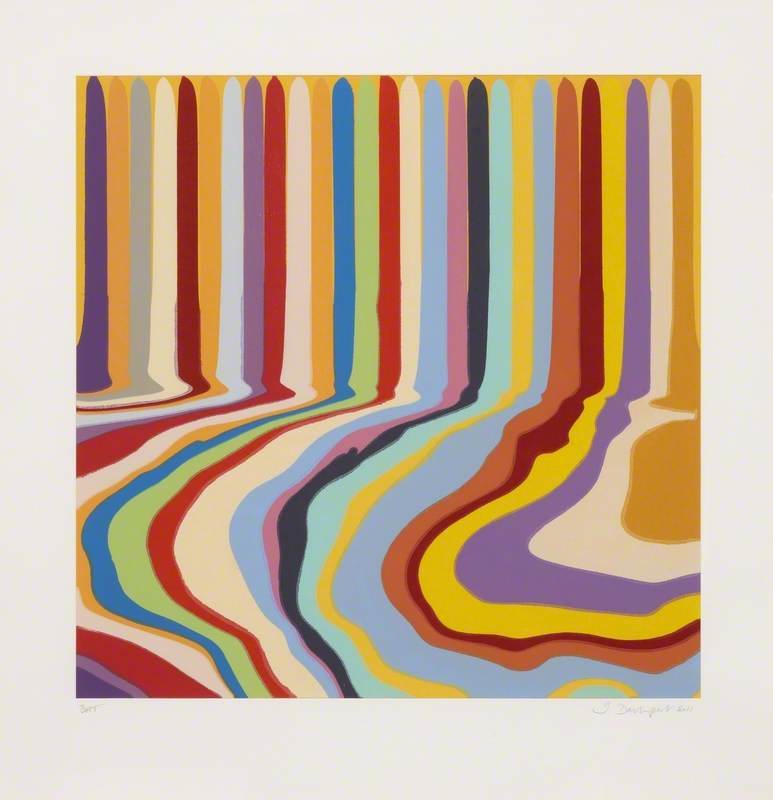

By the early 1990s, Blow found the ever-increasing rent on her beloved London studio at Sydney Close unsustainable. In her late 60s, she decided to relocate to St Ives, where she moved between studios until settling in a converted furniture showroom. Prior to this, she worked for a time in a space which looked out onto Porthmeor beach. Blow became fascinated by the rippling linear sand configurations created by the ebb and flow of the tide, which inspired the zig-zags, triangles and lozenges of works from the early 2000s, such as Tesserae I (2000).

This work on paper looks like a design for a larger piece: the perforated holes where the paper was torn from a sketchpad are still visible down one side. A lattice of diamonds cut carefully from paper overlays a series of thinly applied acrylic marks, the paper itself bearing the traces of what looks like some partially sketched design. Each element of Tesserae I is worked over, bearing evidence of use and life in the studio and the surrounding world.

The term 'tesserae' refers to a small square tablet of wood, bone or ivory once used as a token or ticket; it is also used for the tiny individual squares of tile or glass that make up mosaics. Small though it may be in comparison to her celebrated epic canvases, this rebus-like collage alluding to light on water and architectural patterning exemplifies how, throughout her career, Blow's creations were part of the warp and weft of their environs.

Catherine Spencer, art historian and writer

This content was supported by Jerwood Foundation

Further reading

Michael Bird, Sandra Blow, Lund Humphries, 2005

Sandra Blow, interviewed by Andrew Lambirth, 10 July 1996, National Life Stories, Artist's Lives, British Library Sound Collection, F5201–F5207 from C466/42/01-07

Margaret Garlake, New Art, New World: British Art in Postwar Society, Yale University Press, 1998

Griselda Pollock, 'Feminism, Femininity and the Hayward Annual Exhibition 1978' in Feminist Review 2, 1979

Duncan Robinson, '1970: Sandra Blow' in The Royal Academy of Arts Summer Exhibition: A Chronicle, 1769–2018, 2018

Sandra Blow, exhibition catalogue, Royal Academy of Arts, 1994