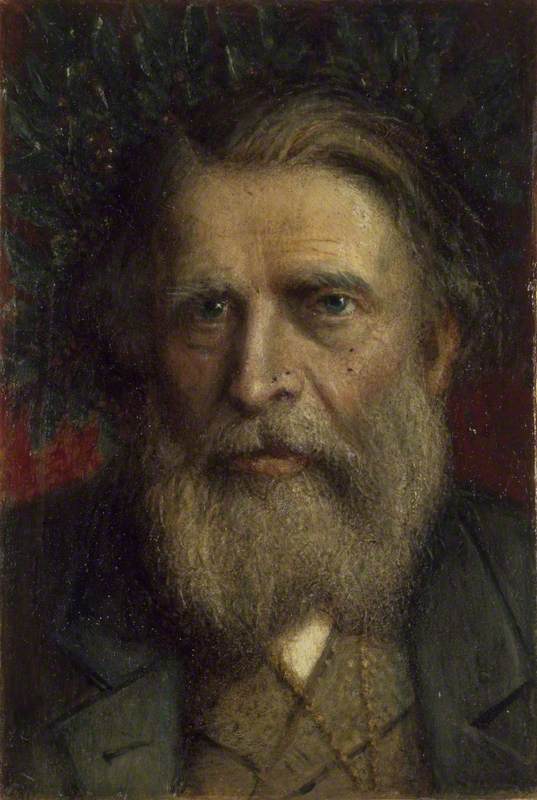

William Morris wrote: 'The true secret of happiness lies in taking a genuine interest in all the details of daily life.' As a designer, poet and activist, Morris was a towering figure in the Victorian art world. His homes became showcases for art and gathering places for writers and radicals. Yet his wife Jane Morris (née Burden), his partner in his creative homemaking, has all too often been overlooked.

Blue Silk Dress (Jane Morris)

1868

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882)

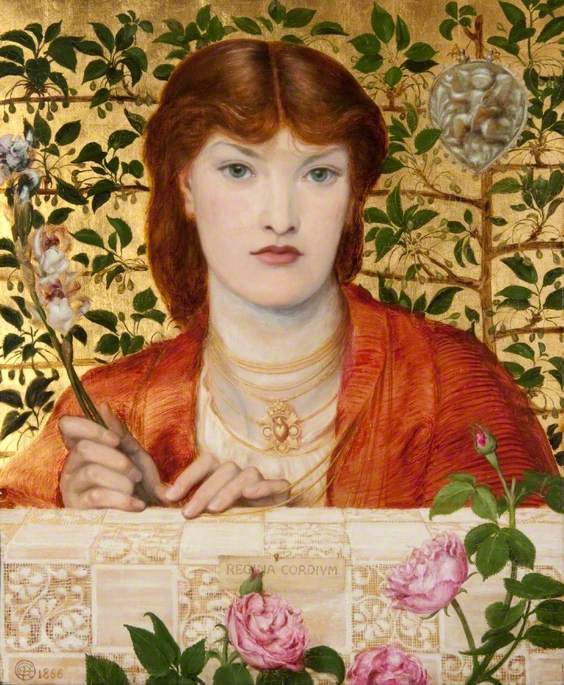

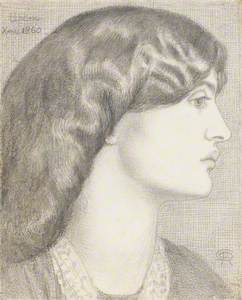

A skilled embroiderer and hostess, Jane was also a celebrated model for the artist and founder of the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood Dante Gabriel Rossetti. She was actively involved in her self-fashioning, and a pioneer of artistic dress. For example, she designed and embellished the unconventional Blue Silk Dress she wears in her portrait from 1868, for which she discussed the details of fit and finish with Rossetti.

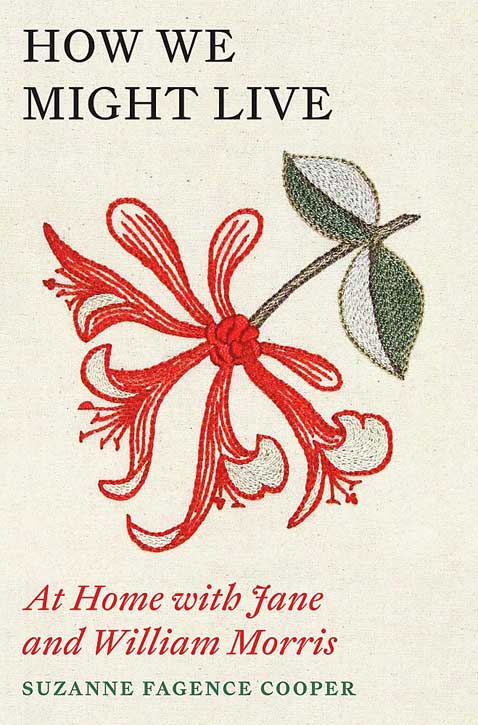

My book How We Might Live: At Home with Jane and William Morris begins at the green edges of London, in William's childhood home, before moving through the cobbled streets of Oxford, then out to a peaceful backwater of the Thames at Kelmscott Manor. At every stage, we see how Jane and William tried to create refuges from the polluted, industrialised environment of Victorian England.

Cover of 'How We Might Live' by Suzanne Fagence Cooper

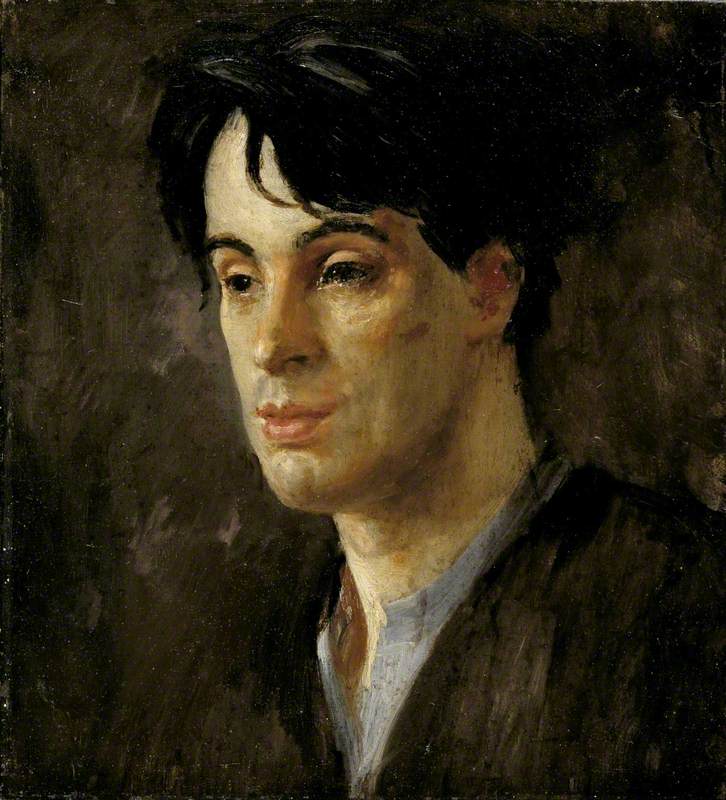

William had a comfortable upbringing and, as a young man, he did not need to earn a living. This meant that he could, as he said, devote his life to art. Jane Burden, on the other hand, was born into poverty. Her mother was illiterate, and her father was a stablehand in Oxford. When Jane was spotted as a potential model, at the age of 17, she was already working – probably as a college servant or laundress. Her encounter with Rossetti and his young artist friends Morris and Edward Burne-Jones was life-changing for them all.

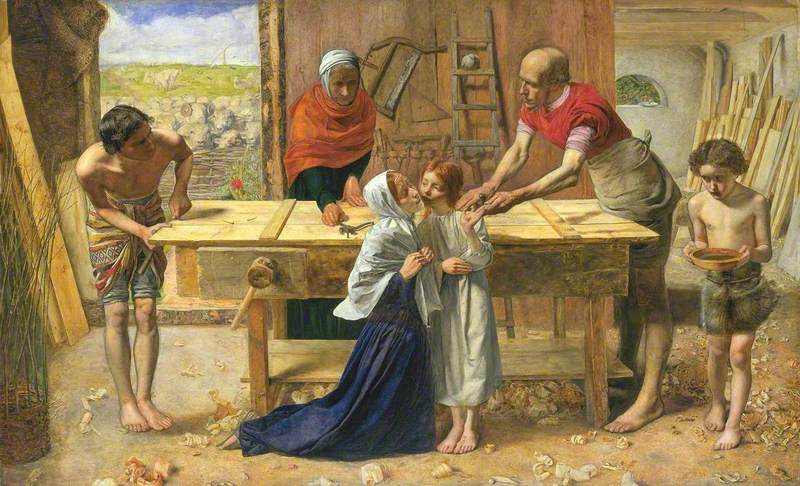

Jane was reluctant to model at first – she did not want to lose her respectable name. But she quickly became a favourite figure within the Pre-Raphaelite circle. Rossetti painted her as Queen Guenevere, and Morris made her the central subject of his only finished oil painting, La Belle Iseult. He is said to have scrawled 'I cannot paint you, but I love you' on the back of the canvas. Certainly by the summer of 1859, they were engaged to be married.

William's picture of La Belle Iseult demonstrated not just his affection for Jane, but his fascination with decorative details. Every surface was covered in medieval textiles, lovingly observed. William paid great attention to the folds and diaper weave in the linen runner, and the fine threadwork of the bed curtains.

His evident delight in Gothic pattern-making and techniques showed the direction in which his art was turning. Soon after their marriage, Jane and William moved to the Red House in Kent, a new home set in an orchard. The architect was their great friend Philip Webb, and together they began to fill the house with extraordinary works of art – stencilled ceilings, painted furniture, and an ambitious series of embroideries to line the walls of the dining room. The figure designs, including Venus by William Morris, were drawn by the men, but the stitching was a massive undertaking for Jane and the other young women who stayed in this 'Palace of Art'.

Venus (or Aphrodite)

1860–1865

William Morris (1834–1896) (attributed to)

Jane's visitors included Rossetti and his wife, Elizabeth Siddal, and Edward and Georgie Burne-Jones. Everyone contributed to the decoration. Georgie remembered the atmosphere in William's studio: 'A most cheerful place it was', with a view onto 'the red-tiled roof... where we could see birds hopping about'. In the garden, and in the half-finished rooms, the friends spent weekends working.

Design for the Decoration of the Red House – The Wedding Procession of Sir Degrevaunt

1860

Edward Burne-Jones (1833–1898)

Burne-Jones took a medieval tale of courtly love, the wedding of Sir Degrevaunt as his inspiration for a series of wall paintings in the drawing room. Rossetti painted subjects by Dante, including Dantis Amor, on the doors of a massive settle.

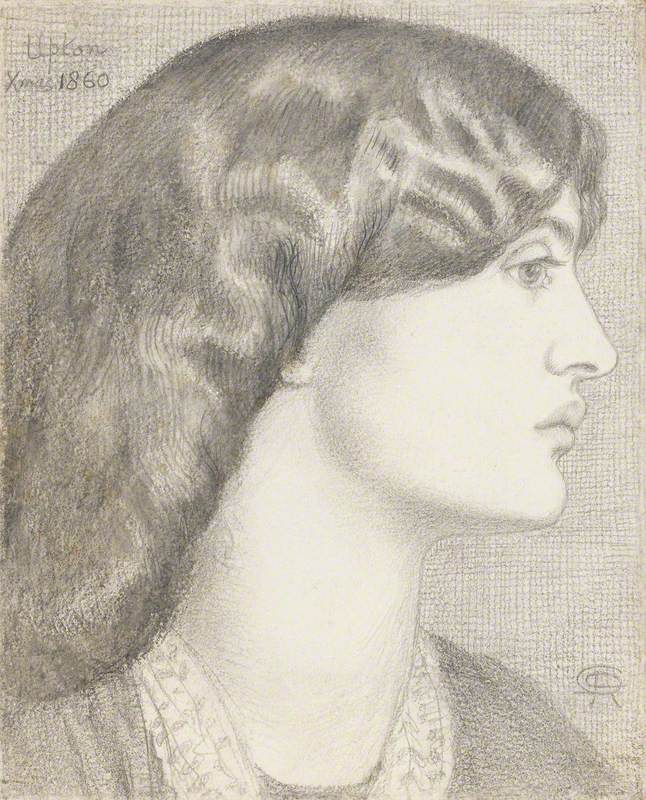

The beloved women – Jane, Lizzie and Georgie – modelled for these romantic images. We can see Jane more directly in a drawing made by Rossetti during the Christmas holidays in 1860. Even though she was heavily pregnant with her first child and entertaining a houseful of guests, she still took time to sit and be studied.

The interior design firm Morris & Co. grew out of the creativity and conversations that the friends enjoyed at Red House. In 1862, they launched the business as 'the only really artistic firm of the kind.' Morris began commuting regularly to meetings in London and in 1865 the family decided to move back into the heart of the city, taking a house with workshops attached in Queen Square.

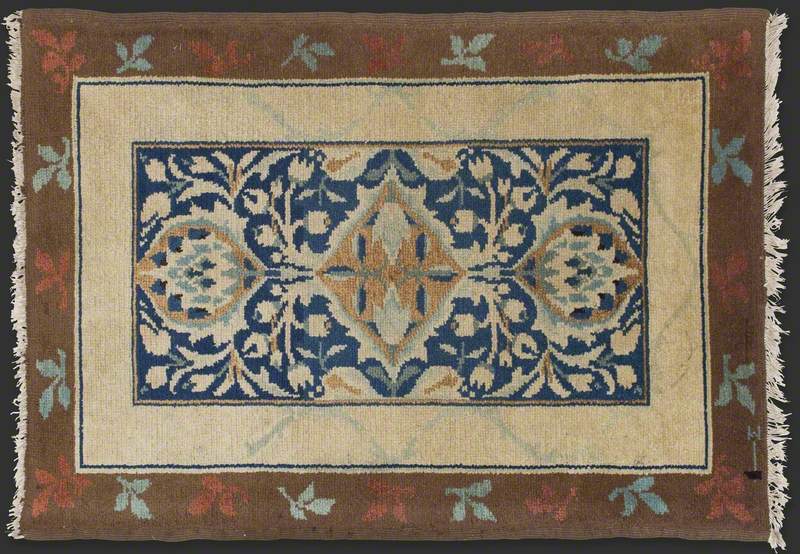

Over the next two decades, the firm was constantly offering new products that were useful as well as beautiful. Many were based on William's passionate research into historical manufacturing processes. He worked hard to perfect dyes and develop his skills in weaving and printing. Jane was in charge of the embroidery department until 1885, supplying gorgeously stitched textiles for homes and churches. By the late 1880s, the Morris and Co. shop in Oxford Street stocked wallpaper, woven fabrics, stained glass, ceramics and rugs.

La donna della finestra

(unfinished) 1881

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882)

The success of the firm changed the dynamics within the Morris circle. William was engrossed in his designs and poetry. By the later 1860s, Jane began to model again in earnest for Rossetti. By 1871, their intimacy had become a closer liaison. Since Elizabeth Siddal's death in 1862, Rossetti had turned to Jane for inspiration. She became La Donna della Finestra from Dante's La Vita Nuova, and Proserpine, the melancholy figure from Greek legend.

William Morris generously accepted that Jane would be happier, at least for a time, in Rossetti's company. William and Rossetti took joint tenancy of a Tudor manor house in Kelmscott, a quiet corner of Oxfordshire. While William went off on a journey into the wilds of Iceland, Jane and Rossetti spent the summer of 1871 at Kelmscott Manor.

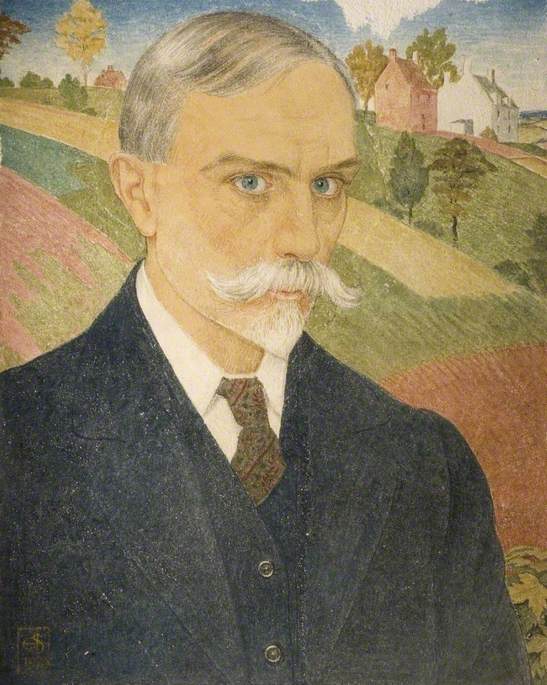

Water Willow

(after Dante Gabriel Rossetti) 1893

Charles Fairfax Murray (1849–1919)

Rossetti recorded this time of seclusion in sonnets and paintings. He later sold his own original Water Willow, a tender portrait of Jane by the river, with the manor house in the background. But his friend Charles Fairfax Murray made a copy, so Rossetti would still have the memory close at hand.

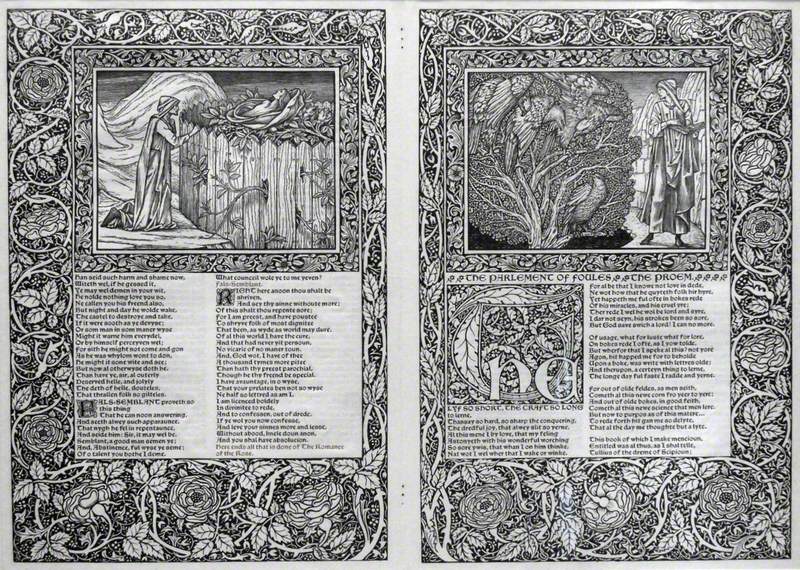

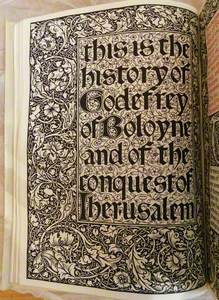

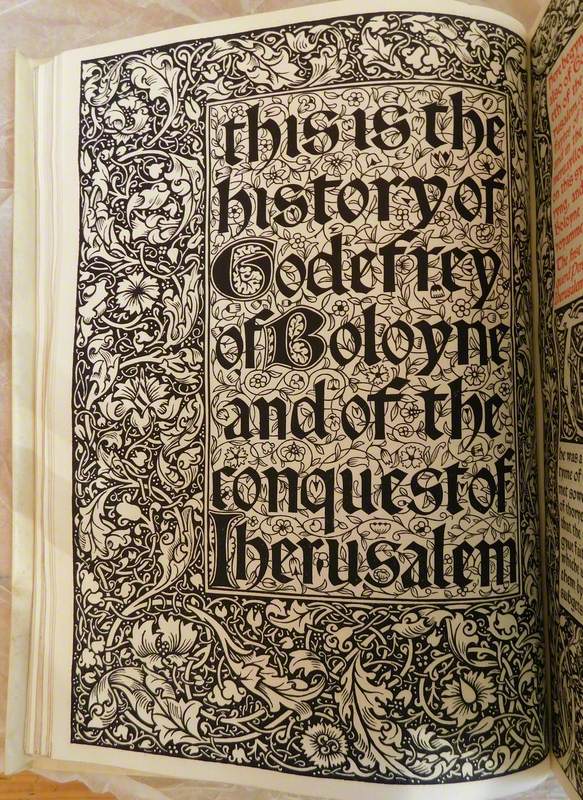

Kelmscott Press Edition of 'Godefrey of Boloyne' by William Caxton

1893

William Morris (1834–1896)

By the late 1870s, Rossetti was troubled by health problems and was addicted to the opiate, chloral. Jane remained an affectionate friend, but the intensity of their relationship was tempered by his increasing ill-health. His later images of Jane lost sight of her practicality and her 'delicious chuckling laugh'. When he painted her as the goddess Astarte Syriaca, Jane found it hard to recognise herself. She called this picture 'My old abomination'.

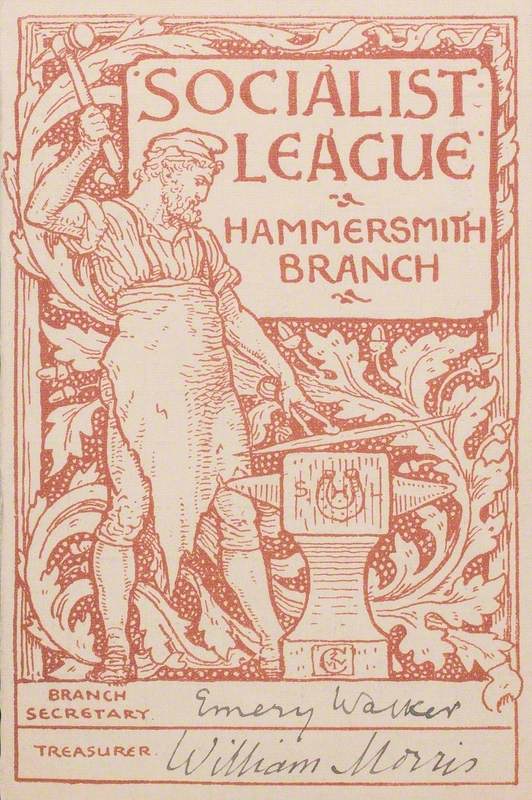

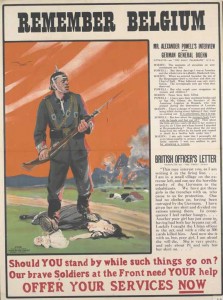

This was a time of great upheaval for William too. After his pilgrimage to Iceland, he became increasingly involved in political activism, and by the early 1880s was devoting much of his energy to the fledgling Socialist cause. He knew that his campaigning led him away from his own 'love of ease, dreaminess, sloth, sloppy good-nature... All these would not have been hurt by my being a 'moderate Socialist''. But it would have been self-deception. He told his friends, 'I cannot help it.'

He set up his own branch of the Socialist League at the family home at Hammersmith. Anarchists, poets and playwrights all found a place at Jane's dining table after the Sunday evening lectures. George Bernard Shaw, Gustav Holst and Oscar Wilde enjoyed her hospitality, alongside Russian refugees and Scottish crofters.

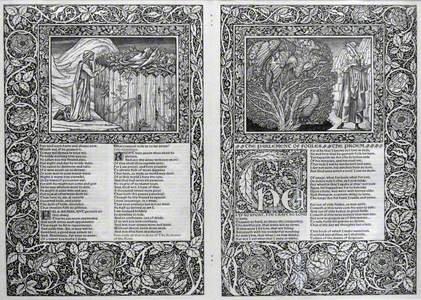

In his final years, William Morris returned to his first love – beautiful books of old tales. He established the Kelmscott Press close to his home, and began printing his favourite stories and poems. At the very end of his life, he created The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer with Burne-Jones, providing the illustrations.

Their handiwork balanced each other. Burne-Jones decided his illustrations 'loved to be snugly cased in borders and buttressed up by the vast initials'. This was William's last great work. His fabled energy was ebbing away: 'The disease was being William Morris and working 18 hours a day.' Jane wrote, with the bad news, to Georgie. She said the doctor had simply explained that William had 'done more work than most ten men'. He died on 3rd October 1896.

Jane Morris, née Burden (1839–1914)

1870s & 1893

Dante Gabriel Rossetti (1828–1882) and Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893)

Jane made the difficult decision to leave the London home, and move some of the family's treasures to Kelmscott Manor. The rest went to museums: the great Persian carpets to the V&A, and Rossetti's sensitive drawings to the Ashmolean, in her home town of Oxford. Soon after William's death, she set off on her own adventure, travelling with their daughter May to Egypt. She stayed in close touch with Georgie Burne-Jones and Philip Webb, and encouraged younger artists, inviting them to find some peace at Kelmscott Manor.

Her obituary, in January 1914, recognised her as 'an exquisite embroideress'. She was remembered too as a model, for 'All the world knows the masses of dark hair, the ivory complexion and exquisite features, the beautiful hands and the great grey eyes'. But then the writer went on: 'Only her intimate friends knew the kindliness, the good sense and the girlish love of fun, which remained until the end of her life.'

Suzanne Fagence Cooper, art historian and author of How We Might Live: At Home with Jane and William Morris, published by Quercus (June 2022)

Browse prints and gifts from the William Morris Society on the Art UK Shop