Women's hats and head coverings in Britain and in Europe have served as a functional protection from cold, the heat of the sun, and from industrial and wartime injury. They have, and can still, indicate rank and social place from the highest to the poorest. They can define a profession or trade and for hundreds of years have reflected a woman's personal embrace of current fashion of her day. The wearing of elegant hats however was, and indeed is, a complex sartorial conundrum.

As in the past – so in the present – not only does the hat have to be correctly styled for the specific social occasions (morning or afternoon wear, cocktail, wedding, funeral summer and winter styles, etc.) but it has also to be worn correctly on the head in order to demonstrate a proper understanding of correct social savoir faire. Personal public humiliation could even be the consequence of wearing a hat at the wrong angle, perhaps too far on the back of head when it should have been worn over the forehead. This was far truer in the nineteenth century and up to the 1960s when all women who could afford to do so wore hats out of doors, even just to go shopping.

There were also strict rules on the use of decorative indoor caps of muslin, lace and ribbon, for day and evening: and on very plain indoor caps for widows, seen so often in portraits of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century women. Hat styles in the nineteenth and twentieth century were created by the famous milliners of Paris and London, with styles changing every season and images diffused widely through fashion magazines.

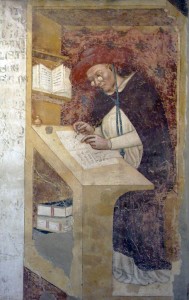

Hats in portraits of women reflect all of these functions and etiquettes, though in Europe from the sixteenth century far fewer had their portraits painted than men, unless they were royal, or aristocratic, or scandalous. Other women achieved the status of a personal portrait from the eighteenth century onwards if their family and husbands were wealthy. Some few were painted if they had excelled publicly in some way – on the stage, and by the later nineteenth century in the world of academia, politics, sport, local government, literature or medicine, for example. Poor and country women were painted often at their work, by genre artists, keen to catch the character of worn faces and rough, unfashionable clothing. Portraits of women who had committed acts of great bravery in wartime are also to be found too in our museum and galleries.

Many portraits also however simply celebrated the fashionability and elegance of the hats of comfortably off women, providing a lasting memory space through which to celebrate the creativity of milliners, whether professional or amateur. From the mid-eighteenth century, once versions of fashionable dress were seen in the clothes of middling class women, milliners vied to produce the latest, newest hat styles, using the latest vogue in hat fabrics and trimmings: the finest woven straws from Italy and the East of England; exotic silk fabrics and jewels from India made into turbans; perfectly made silk flowers of every type and size; and costly feathers from peacocks, hummingbirds and egrets. Ostrich plumes were a particular favourite because of both their high price and the beautiful movement of their soft fronds.

Summer beach hat design: red flowers on white straw

1962, gouache & pencil by Lou Taylor

With all this in mind, here is a selection of images from Art UK to celebrate the use of hats by women in Britain from the early sixteenth century onwards.

Bejewelled hats and headdresses

Amongst the really rich, hats could be trimmed with all kinds of exotic jewellery, even through to the twentieth century.

Emilia was one of three daughters of Duke Heinrich of Frommen, and is shown here wearing gold lace bows and braiding in her turban-style hat, with four gold necklaces around her throat and shoulders.

Catherine of Würtemberg (1783–1835), Wife of Jérôme Bonaparte, King of Westphalia

c.1810–1820

François Joseph Kinsoen (1771–1839)

Queen Catherine wears a highly fashionable pink silk headdress designed to match her high-waisted dress. Rows of small luxurious pearls dangle over her ear.

Hats and ostrich plumes

Ostrich plumes were a particular favourite hat and fan trimming from the sixteenth century. They were extremely fashionable and vastly expensive in the late eighteenth century, imported from Africa and much favoured by Queen Marie Antoinette and the women at her court.

This painting offers a clear image of a fashionable hat of the Regency period trimmed with white satin ribbons, lace and beautifully drooping white ostrich plumes.

The artist has focused on the brightness of the turquoise-blue feathers on the somewhat battered straw hat worn by this street flower seller as a mark of her trade. By this date, ostrich feathers were imported into London in large quantities and qualities from South Africa. She was a forerunner of the coster-girls, so frequently drawn by Phil May, at the turn of the nineteenth century, famous for their neatly fitting ready-made tailored costumes and the huge bright ostrich plumes on their large hats.

This bonnet, about 20 years out of date for its day, shows the use of curled ostrich feathers in the stole and shaded feather, from white to dark blue in her hat, which is about 10–20 years out of date in style. Miss Easton died on Christmas day in 1914 at the age 95, and left jewellery and furniture to her companion, £3,000 to her gardener and £10,000 to Newcastle Medical College. The portrait is dated to 1914 and might have been commissioned after her death.

Hats for weddings and funerals

Correct hat etiquette was a deep concern at public events such as weddings and funerals.

This scene shows a bride being fitted for her wedding dress by her dressmaker, whilst her mother looks on. By the mid-ninteenth century, well-off brides married in white, with headdresses of wax orange blossoms under long silk net veils or lace veils.

As the leading genre artist of the Newlyn School, Stanhope Alexander Forbes painted many aspects of the lives of Cornish fishing communities. Here he celebrates a wedding in an inn: the groom in his sailor's uniform, some guests, maybe the bridesmaids, in smart styles, and the bride, all in white with a charming wreath of white flowers and veil.

Marie Antoinette (1755–1793), Queen of France, as a Widowed Prisoner in the Temple, 1793

Alexander Kucharski (1741–1819) (after)

After the execution of her husband Louis XVI on January 21st 1793, Queen Marie Antoinette, imprisoned in the Temple, Paris, was famously sketched by Kucharski. She wore formal court mourning for the last nine months of her life. Once so renowned for her extravagant ostrich feather-plumed hats, here she wears an etiquette-correct black veil probably of silk crepe, with plain white edging. She was executed on 16th October 1793.

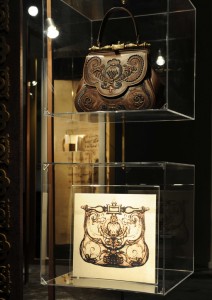

Hats and lace

Lace has been a key status element in hat decoration over many centuries, with lace qualities varying from the most expensive handmade designs of the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries, down to mass-production yardage. Depicting the fineness and intricacy of costly lace posed a specific task of accuracy to painters.

This portrait reflects the fashion for remarkably tall hair styles in the 1770s. It shows a fashionable elderly woman wearing a high hat trimmed with lace, swathes of soft silk and a striking blue and white ribbon, over her powered hair.

Margaret, née Salter (1780–1863), was the wife of William Stancome, a well-off clothier from Trowbridge. She is shown here wearing a most becoming indoor cap, with her fashionable green silk, balloon-sleeved dress with its fine-blonde lace shoulder shawl. Her elegant little lace-trimmed cap features white artificial silk roses and small, leafy rose buds around her ears.

Women at work

Women's hats and head coverings can indicate, as shown in these examples, profession, trade and class. They can also indicate fashionability, age, nationality and even dissident rejection of the accepted styles of the day.

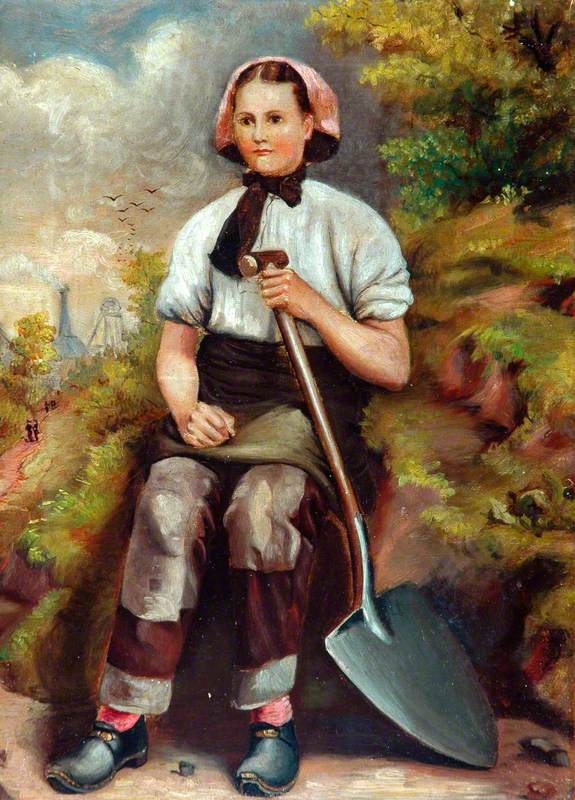

Once laws were established in 1840 which banned women from underground work in coal mines, many undertook heavy shovelling work above ground at collieries in Wales, Scotland and England through to the early twentieth century. Whilst some women wore long sturdy skirts, others wore men's trousers with thigh-length short sacking skirts, rough blouses and hob-nailed clogs or boots. Their hair was always covered as protection from coal dust and filth, either with short tied-back scarves, rough home-made hats, or fringed shawls. This rare oil portrait shows a pit brow girl wearing a hat, probably home-made, made of pink cloth tied securely under her chin with a black bow. (See Alan Davis' 2002 book The Pit Brow Women of Wigan Coalfield, published by The History Press for more information.)

Julia Anne Hornblower Cock (1860–1914), MD, studied at Bedford College in the early 1880s, and by 1891 was a qualified physician living at Manchester Square, Marylebone in London. In 1896 she taught as a lecturer at the London (Royal Free Hospital) School of Medicine for Women. In 1903 she became Dean of the college, replacing Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, who had been Dean since 1883. In 1877 the Royal Free Hospital was the first teaching hospital in London to admit women for training. She is shown here in the formal university robes of a Dean, wearing her mortar board.

Madge Garland was one of Britain's most famous fashion and interior design journalists and writers. She took over the editorship of English Vogue in 1933 and founded the Fashion programme at the Royal College of Art in 1947. This portrait presents her as profoundly smart – every inch the fashion editor – in the fashionable sportive style of summer leisure wear of the late 1920s, typified by her large straw hat but also by her faux-casual pink dress and dark blue jacket.

This portrait shows a young woman wearing the uniform of a waitress, in 1941, in the third year of the Second World War. She wears a black uniform dress with a starched white cotton uniform cap, trimmed with broderie anglaise lace and open work, matching her collar, apron and cuffs. By December, once women aged 20–30 were called up for war service, unless she had children, this woman was probably recruited to play a far more active role in the Second World War.

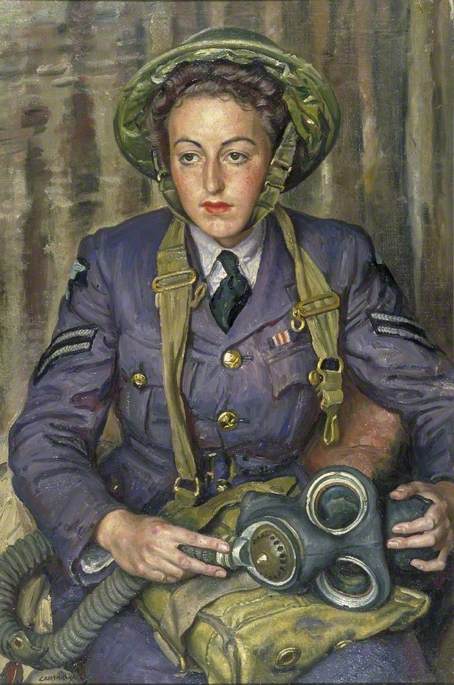

Corporal J. M. Robins, Women's Auxiliary Air Force

1941

Laura Knight (1877–1970)

Josephine Maude Gwynne Robins is shown with her protective tin helmet, her blue WAAF uniform and with a gas respirator on her lap. The WAAFS were established in 1939. The London Gazette of 20th December 1940 reported that: 'Corporal Robins was in a dug-out which received a direct hit during an intense enemy bombing raid. A number of men were killed and two seriously injured. Though dust and fumes filled the shelter, Corporal Robins immediately went to the assistance of the wounded and rendered first aid. While they were being removed from the demolished dug-out, she fetched a stretcher and stayed with the wounded until they were evacuated. She displayed courage and coolness of a very high order in a position of extreme danger.'

Lou Taylor, Professor of Dress and Textile History, University of Brighton, and Dress and Textiles Group Leader for Art Detective

Further reading

Sarah Abrevaya Stein, Plumes: Ostrich Feathers, Jews and the Lost World of Global Commerce, Yale University Press, 2008

Stephen Jones, Hats: An Anthology, V&A Publishing, 2012